Navy On The Rhine - 1945-04-27

By Sgt. Ed Cunningham, YANK Staff Correspondent

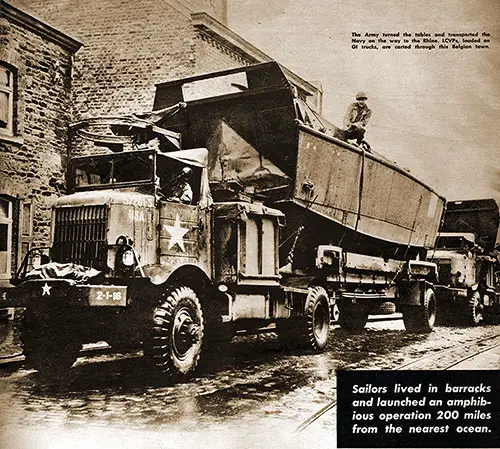

The Army Turned the Tables and Transported the Navy on the Way to the Rhine. LCVPs, Loaded on GI Trucks, Are Carted Through This Belgian Town. Sailors Lived in Barracks and Launched an Amphibious Operation 200 Miles from the Nearest Ocean. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d949eed62

With the U. S. Navy on the Rhine—The day the Ninth Army crossed the Rhine River was the screwiest 24 hours of the 20 years that CWO John (Chips) Dauphinais has served in the U. S. Navy.

First off, there was the strictly unnautical experience of riding in a boat carted on an Army truck over dusty, shell-pitted roads that were zeroed in by German 88s.

Then came a two-hour heave-to in a blasted German village, waiting for an ammo dump ignited by enemy artillery to burn itself out so Chips' boats could be trucked over the Rhine dykes Without silhouetting them to enemy guns across the river.

Next came the sacrilegious breaching of Naval procedure in the way the LCMs and LCVPs had to be launched on the Rhine.

Instead of being let down gently from a ship's davits v.in approved Navy style, the boats were dropped by cranes operated by the Army Engineers or batted in by bulldozers. Amid all this were frequent trips to nearby foxholes while Jerry mortars and 88s splattered the west bank.

The final blow was the precedent-breaking experience of taking naval craft into action on a river no more than 350 yards wide and 200 miles from the nearest ocean.

Although not steeped in naval tradition like his trip on Old Ironsides when it made its farewell tour of the US or his service on a destroyer in the South Pacific during the critical days of 1942, the Rhine crossing was still a day that Chips can dwell upon long, if not longingly, when he tells his grandchildren back in Nashua, N. H., about his 20 years in the Navy.

CWO John (Chips) Dauphinais wears Army fatigues. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d94a78302

Chips and other members of CDR William D. J. Whitesides' Naval Task Group, which operated with the First, Third, and Ninth Armies in their successful crossing of the Rhine, were not in the largest combined operation of the war. Still, they were undoubtedly unique.

Never before have U. S. naval units gone into action with the Army 200 miles from an ocean. Likewise, this was the first time in history that the Army had called on the Navy to support an inland-river crossing.

Three hours after the first assault troops hit the east bank of the Rhine in the Ninth Army sector, the Navy delivered tanks and TDs to them to knock out the enemy strongholds holding up the advance.

German mortars and air bursts were blanketing the river and beaches when Coxswain G. Jaryzisky of Bowling Green, Ohio, guided his 50-foot LCM No. 33 onto the far bank of the Rhine with a Sherman tank.

Only a few minutes after shoving off from the west bank, he was back to pick up a TD for which the Army had sent an urgent request.

After making his second trip across with the Sailors lived in barracks and launched an amphibious operation 200 miles from the nearest ocean.

TD, Jaryzisky turned his 26-tori craft downstream toward a site where U. S. troops on the far bank needed armor ferried to them. While he was in midstream, a German 88 opened up on him.

The first shell was high, but the next two were near misses on the port quarter and sprayed the LCM with shrapnel. The boat's two .50-caliber machine gunners and signalman were injured and had to be evacuated. Lt. (JG) Richard Kennedy of Los Angeles, Calif., who was in command at the ferry site, also was aboard.

He got a superficial chin wound but did not require hospitalization. Jaryzisky and his engineer, Richard Graham Sic of Elmwood, Wis., escaped unhurt and continued to ferry supplies and troops across for the next two days of the operation at that site.

Another LCM was hit by an 88 at the beach site just as it was to be unloaded from its trailer. The shell ripped a hole in the bow ramp but caused no further damage.

Half an hour later, the LCM was operating as a Rhine ferry with Coxswain William D. J. Murray of Bayonne, N. J., at the helm. Once the buildup of supplies and men had been completed on the Ninth Army front, the Navy craft switched over to help the Combat Engineers construct Treadway and ponton bridges.

They towed bridge sections in place and held them fast while engineers put in their upstream anchors. After that, the LCMs and LCVPs patrolled the Rhine to protect the newly constructed bridges from floating mines and debris.

For five months preceding the inland naval operation, the Navy's small-boat crews lived and dressed as soldiers to maintain the secrecy which covered the preparations for the Rhine crossing.

They trained with combat engineers, to whom they were attached, on rivers in Holland and Belgium, perfecting the new amphibious technique that the peculiar nature of their assignment demanded.

Instead of guiding their boats through tossing waves and rolling surf as they had done in North Africa, Sicily and Normandy, the small-boat men had to learn to maneuver their craft to and from pinpoint landing spots in swift sidewise currents in which they had never had to operate before.

While the initial plans were being made for the crossing, the Allied High Command decided on a combined air, sea, and land operation as the most practical method of storming Germany's age-old defensive barrier to invasion.

Parachute and glider troops were to be used to secure the east bank of the Rhine and its approaches so that the Infantry assault troops could get ashore without having to meet the all-out defenses of the Germans.

The unexpected capture of the bridge at Remagen somewhat modified these plans. This took the initial brunt of the burden off the airborne troops. Several bridgeheads were planned, but the problem of supplying initial assault troops loomed as a significant threat to the operation's success. The width and current of the Rhine were expected to make the construction of bridges very difficult.

So, as initially planned, the Army counted on the naval craft to build up the force on the east bank between the initial crossings and the completion of the bridges. The bow-ramp construction of the LCMs and LCVPs made them ideal for quick transportation, permitting loaded vehicles to be driven on and off without reloading.

The Engineers stated that without naval craft, a crossing of the Rhine could not be made until mid-June when the spring thaws were over. That's why the Navy got to ferry the Army across the Rhine.

German Prisoners Were Carried Back to the West Bank of the Rhine in Landing Boats. Prisoners on This Boat Fish Some Comrades Out of the Drink. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d94ceeb76

The Navy unit assigned to the First Army was the first to arrive on the Continent. Its personnel went into training last October at localities in Belgium whose terrain approximated the probable Rhine crossing sites. They practiced daily with engineers on the Manse River, launching boats and loading and unloading all types of cargo.

The challenging problem the Navy had to beat was the freezing conditions in river navigation. The cooling systems of their boat engines were designed for salt water, which, of course, never freezes.

So a new cooling system had to be worked out. Ice in the river was another headache, and guards had to be improvised to protect the screws.

But the biggest headache came when the crews started to move their craft toward the Rhine over hundreds of miles of blasted roads. On its truck carrier, an LCM is 77 feet long (equivalent to the height of a seven-story building), 14 feet wide, and nearly 20 feet high. That made moving them over shelled roads and narrow village streets a challenging problem.

While passing through one German town, the LCMs reached a narrow street where they needed more room to turn a corner. Ironically enough, one of the few relatively undamaged houses in the village was situated right on that corner, blocking the boats' passage.

There was no alternative route through or around the village. So the Army convoy officer with the Navy crews did the inevitable. He knocked on the door of the house holding up the Navy.

When its rather timid German owner answered, the Army officer said: "How do you do? I just came to tell you you'll have to evacuate immediately. We gotta blow up your house." Shortly afterward, a combination of dynamite and a bulldozer cleared a "channel" for the Navy.

When the Germans launched their Ardennes offensive in December, the First Army sailors had to fall back along with the soldiers. During the breakthrough, they had plans to destroy their boats if trapped.

Daily drills were staged so no time would be lost if a "scorched sea" policy became necessary. The LCVPs, mainly made of plywood, were to be drenched with gasoline and burned, and the all-steel LCMs were to be burned out and sunk.

These drastic measures were unnecessary, as the Germans never got that close. However, they forced the Navy to evacuate several of its billeting sites.

During the hectic weeks of the Ardennes campaign, the sailors were quartered successively in a bombed-out factory, a town hall, a restaurant, a theater, a grammar school, and private houses.

Living as soldiers and dressing in ODs, helmets, and GI shoes didn't make dough feet out of the sailors. Still, it did bring about a slight change in their vocabularies. Instead of using such Navy terms as "head" and "quarterdeck," the land-based sailors often found themselves slipping up and unconsciously referring to "latrines" and "CPs."

But the language change worked both ways, as several Army engineers working with the Navy soon discovered. GIs started speaking of "floors" as "decks" and using "topside" for "upstairs."

Although conforming to Army life in dress and speech, the Navy men remained conscientious objectors to Army chow. They ate C-rations and K-rations when nothing else was available.

But whenever possible, they sent out a detail to the nearest U. S. Navy advance base to draw certain delicacies never found on the Army's menus.

Cooking Lunch in Front of Their Boat (L. To R.) Coxswains Frank Potyrolo, Harry Atkins, and James Pizzano GM3c—All in on the Rhine Crossing. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d9518e3d3

The Old Navy CPOs' regard for Navy tradition took a hell of a beating under the Army life. Their chief objection was to the drab OD uniforms and the reversed-calf shoes they had to wear instead of their spotless blue and shiny black uniforms. Another affront to their pride was that even their boats became GI, with their hulls painted olive drab.

But the story which the Old Navy men will never be able to live down is how one of their select circles got the Purple Heart hundreds of miles from an ocean and not even close to a good river.

Chief Machinist James L. Trammell of Beaumont, Tex., was in Aachen, trying to find spare parts for his boats, when German artillery started shelling the town. Trammell had stretched out under an Army jeep when shrapnel hit him in his hand.

He got the Purple Heart for his wounds but didn't keep it long. Abashed by the circumstances of his decoration, he later gave the medal to a little Belgian girl who had been injured when a buzz bomb hit her home.

Another incident showed that the Navy would never put too much faith in the Army. The night the Ninth Army jumped off, a convoy sited was halted on a narrow German road.

The LCMs and LCVPs being trucked to their ferry boats were still half a mile from the Rhine and about the same distance in front of a battery of American heavy artillery.

One LCM crewman decided to sleep in his boat for a couple of hours. Still, before doing so, he carefully set his alarm clock for when the Army would launch its most extraordinary artillery barrage of the war. The convoy was to wait until 0200, when it would proceed to beaches under cover of the artillery barrage scheduled to start at that time.

EVERY detail of the new amphibious technique had been perfected when the unexpected capture of the Remagen bridge took the edge off the combined operation set up by the Allied High Command for storming the Rhine.

But the Army still needed the Navy to provide the quick buildup of troops, weapons, and supplies to support the first elements of the 9th Armored Infantry crossing the Rhine at Remagen.

So the Navy task unit assigned to the First Army began ferrying men and vehicles across the river in LCVPs. At the same time, ponton and Treadway bridges were being constructed to ease the traffic load on the captured bridge.

Instead of Being Lowered from Their Mother Ships, Landing Craft Was Dunked in the Rhine by Cranes. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d957326b1

The first U. S. naval vessel ever to cross the Rhine touched on the east bank at 1140 hours on March 9, with reinforcements for the First Army troops then fighting to extend their bridgehead.

It was a 36-foot LCVP manned by Roy L. Stull Sic of Bergoo, W. Va.; Gordon T. Simmons Sic of Turlock, Calif.; Theodore M. Stratton Sic of Long Beach, Calif., and J. C. Alger Sic of Boonville, N. Y.

While ferrying the 1st Infantry Division across the Rhine in the First Army bridgehead sector, some of the crews of the Navy small boats recognized men of the "Red One" Division whom they had taken into Omaha Beach on D-Day.

All the Navy crew members taking part in the Rhine operations were veterans of at least one amphibious-assault landing. Some had operated landing craft in all four significant landings in the ETO—North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy.

During the crucial days of the Remagen bridgehead, they flushed out two members of the German "Gamma" swimmers who had been sent out to blow the Rhine spans used by the Americans.

The "Gamma" swimmers could swim underwater indefinitely, equipped with oxygen helmets, rubber suits, and duck feet. But they were forced to the surface, where the Army guards captured them.

The Remagen Bridge, Before It Collapsed into the Twisted Wreck Above, Was an Unexpected Dividend for Allied High Command River-Spanning Operations. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d957723d4

Intense artillery fire, which the Germans leveled on the Remagen bridge, failed to stop the Navy's regular patrol of the Rhine. Nor did it stop the patrol from doing a little shooting of its own.

The Army credited one LCVP crew with shooting down a Focke-Wolfe 190, which attacked the bridge. Operating the boat's .50-caliber machine gun at the time was 19-year-old Calvin Davenport Sic of Rocky Mount, N. C.

With him on the boat was Coxswain Philip E. Sullivan of Suffolk, Va.; Donald C. Weaver MoMM3c of Indianapolis, Ind., and Irving T. Sanford Sic of Greensboro, N. C.

In the Rhine Crossings, Coxswain Eurene Platoni Had His LCVP in the First Wave of Boats over the River. He Had the Same Job in Normandy on D-Day. YANK, 27 April 1945. GGA Image ID # 1d95f72b8a

Navy LCMs and LCVPs were also used in the Third Army's crossing of the Rhine, which came unexpectedly the day before the Ninth Arnjy jumped off. The Third Army's naval unit, which had trained on the Moselle River, was quartered in an old French cavalry barracks during its pre-invasion maneuvers.

German soldiers, who had previously occupied the barracks, had painted a sign "Adolf Hitler Kaserne" over the front entrance. When the U. S. Navy steamed in, the sailors rechristened it the "USS Blood and Guts."