Coal Used in Steamships - 1887

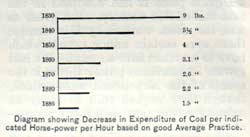

Diagram showing Decrease in Expenditure of Coal per indicated Horse-power per Hour based on good Average Practice.

The year 1855 marks the high-water mark of the paddle-steamer era. In that year were built the Adriatic, by the Collins line, and the Persia, as a competitor (and the twenty-eighth ship of the company), by the Cunard. But the former was of wood, the latter of iron.

She was among the earlier ships of this material to be built by the Cunard company, and, with the slightly larger Scotia, built in 1862, was, for some years after the cessation of the Collins line, the favorite and most successful steamer upon the Atlantic.

She was 376 feet long, 45 feet 3 inches broad, and of about 5,500 tons displacement. Her cylinders were 100+ inches diameter, with 120 inches stroke, and she had—as also the preceding ship, the Arabia—tubular boilers instead of the old flue.

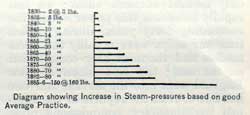

Diagram showing increase in Steam-pressures based on good Average Practice.

How great an advance she was upon their first ship will be seen by the following comparison :

| Britannia | Persia | |

|---|---|---|

| Coal necessary to steam to New York | 570 tons | 1,400 tons |

| Cargo carried | 224 tons | 750 tons |

| Passengers | 90 | 250 |

| Indicated power | 710 | 3,600 |

| Pressure per square inch | 9 lbs. | 33 lbs. |

| Coal per indicated horse-power per hour | 5.1 lbs. | 3.8 lbs. |

| Speed | 8.5 knots | 13.1 knots |

Thus, for two and a half times the quantity of coal nearly three and a half times the cargo was carried, and nearly three times the number of passengers.

This result was due partially to increased engine efficiency, and partially to increased size of ship; and thus to a relative reduction of the power necessary to drive a given amount of displacement.

The Scotia was almost a sister ship to the Persia, slightly exceeding her in size, but with no radical differences which would mark her as an advance upon the latter.

She was the last of the old régime in the Atlantic trade, and the same year in which she was built saw the complete acceptance by the Cunard company of the newer order of things, in the building of the iron screw steamer China, of 4,000 tons displacement, with oscillating geared screw engines of 2,200 indicated horse-power, with an average speed of 12.9 knots on a daily expenditure of 82 tons of coal.

She was the first of their ships to be fitted with a surface condenser. The Scotia had been built as a paddle steamer rather in deference to the prejudices of passengers than in conformity with the judgment of the company, which had put afloat iron screw ships for their Mediterranean trade as early as 1852 and 1853.

The introduction of surface condensation and of higher pressures were the two necessary elements in a radical advance in marine engineering. Neither of these was a new proposal; (Note 535-A) several patents had been taken out for the former at a very early date, both in America and in England; and in 1838 the Wilberforce, a boat running between London and Hull, was so fitted.

Very high pressures, from almost the very beginning, had been carried in the steamers on our Western waters; and in 1811 Oliver Evans published, in Philadelphia, a pamphlet dealing with the subject, in which he advocated pressures of at least 100 to 120 pounds per square inch, and patented a boiler which was the parent of the long, cylindrical type which came into such general use in our river navigation.

The sea-going public resolutely resisted the change to high pressures for nearly forty years, there being a very slow and gradual advance from 1 and 2 pounds to the 8 and 9 carried by the Great Britain and Britannia. In 1850 the Arctic carried 17, and in 1856 25 was not uncommon.

Some of the foremost early English engineers favored cast-iron boilers (see evidence before parliamentary committee, 1817); and the boiler in general use in England up to 1850 was a great rectangular box, usually with three furnaces and flues, all the faces of which were planes. (Note 535-B)

Though tubular boilers did not displace the flue boiler in British practice to any great degree before 1850, many examples were in use in America at that date, but chiefly in other than sea-going steamers. Robert L. Stevens, of Hoboken, built as early as 1832 " the now standard form of return tubular boilers for moderate pressures " (Professor R. H. Thurston).

But it worked its way into sea practice very slowly; and the multi-tubular boiler, in any of its several forms, cannot be said to have been fairly adopted in either American or British sea-going ships before the date first mentioned, though employed in the Hudson River and Long Island Sound steamers, in one of the former of which, the Thomas Powell, built in 1850, a steam pressure of 50 pounds was used.

There had been this slow and gradual advance in ocean steam pressures, with a consequent reduction in coal expenditure, when in 1856 came a movement in the direction of economy by the introduction of the compound engine, by Messrs. Randolph Elder & Co. (later John Elder & Co.), which was soon to develop into a revolution in marine steam enginery.

The Pacific Steam Navigation Company has the credit of first accepting this change in applying it to their ships, the Valparaiso and Inca. The original pressure used was 25 pounds to the inch; the cylinders were 50 and 90 inches in diameter, and the piston speed from 230 to 250 feet per minute.

The idea of using steam expansively by this means was of course not new, as it dates back to Hornblower (1781), but with the low pressures which had been used at sea there was no reason for its adoption afloat.

Difficulties were experienced by the Pacific Company with their earlier engines, but the line adhered to their change, and for nearly fourteen years were almost alone in their practice.

These changes made the use of a cylindrical boiler necessary, as the form best able to withstand the increased pressure. The old box-like shape has disappeared; and if the shade of Oliver Evans is ever able to visit us, it must be with an intense feeling of satisfaction to find his ideas of eighty years since now accepted by all the world.

The date 1870 marks the advent of a new type of ship, in those of the Oceanic Company, better known as the White Star line, built of iron by Harland & Wolff, of Belfast—engined with compound engines, and of extreme length as compared with their breadth.

They established a new form, style, and interior arrangement, which has largely been followed by other lines, though the extreme disproportion of length and beam is now disappearing.

The Britannic (page 523) and Germanic, the two largest of this line, are 468 feet in length and 45 feet 3 inches in beam, carrying 220 cabin passengers and 1,100 in the , besides 150 crew.

They develop 5,000 indicated horse-power, and make their passage, with remarkable regularity, in about 8 days 10 hours to Queenstown. The earlier ships of this line, when first built, had a means of dropping their propeller-shaft so as to immerse more deeply the screw; so many inconveniences, however, were associated with this that it was given up.

Their general arrangement was a most marked advance upon that of their predecessors—an excellent move was placing the saloon forward instead of in the stern, a change almost universally followed. This line may be looked upon as one of the most fortunate between England and America.

Of moderate cost, good speed, with low coal consumption (for the time when built), and with advanced arrangements for the comfort of passengers, it has held its own against newer and somewhat faster ships, though none of the White Star vessels now running between Liverpool and New York are less than thirteen years old.

In the same year with the Britannic came out the City of Berlin, of the Inman line, for some years the largest steamer afloat (after the Great Eastern), being 520 feet in length by 44 feet beam, of 5,000 indicated power, and in every way a magnificent ship.

The Bothnia and Scythia were also built in 1874, by the Cunard company, as representatives of the new type, but were much smaller than the preceding.

They were of 6,080 tons displacement and 2,780 indicated horse-power, with a speed of 13 knots. The pressure carried was 60 pounds.

These ships had by far the largest cargo-carrying capacity (3,000 tons measurement) and passenger accommodation (340 first-cabin) of any yet built by the company.

With the addition of this great number of steamers, change was not to be expected for some years; and it was not until 1879, when the Guion company put afloat the Arizona, that a beginning was made of the tremendous rivalry which has resulted in putting upon the seas, not only the wonderful ships which are now running upon the Atlantic, but in extending greatly the size and speed of those employed in other service.

Several things had combined in the latter part of this decade to bring about this advance. The great change between 1860 and 1872, from the causes already noted, which had reduced coal consumption by one-half, was followed by the introduction of corrugated flues and steel as a material for both boilers and hull.

With this came still higher pressures, which were carried from 60 to 80 and 90 pounds. In August, 1881, a very interesting paper was read by Mr. F. C. Marshall, of Newcastle, before the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, in which he showed that a saving of 13.37 per cent. in fuel had been arrived at since 1872.

The general type of engine and boiler had remained the same in these nine years, but the increased saving had been due chiefly to increased pressures.

It is curious that at the reading of both the paper by Sir Frederick Bramwell, in 1872, and that of Mr. Marshall, in 1881, there should have been pretty generally expressed a feeling that something like a finality had been reached.

So little was this opinion true that, though over thirteen per cent. saving had been effected between these two dates, a percentage of gain more than double this was to be recorded between the latter date and 1886.

In these matters it is dangerous to prophesy; it is safer to believe all things possible. Certainly, the wildest dreamer of 1872 did not look forward to crossing the Atlantic at nearly 18 knots as a not unusual speed.

In 1874 triple expansion engines had been designed for the Propontis by Mr. A. C. Kirk, of Napier & Sons, of Glasgow, which, on account of failure in the boilers which were used, did not give at first the results hoped for.

In 1881 the Messrs. Napier fitted the Aberdeen with engines of the same kind, steam at 125 pounds pressure per square inch being used. In the next two years the change proceeded slowly, but by 1885 the engineering mind had so largely accepted it that a very large proportion of the engines built in that year were on this principle, and at the present it may be regarded as being as fully accepted as was the compound engine ten years since.

The saving in fuel is generally reckoned at from twenty to twenty-five per cent., or, to put it more graphically, in the words of Mr. Parker, Chief Engineer Surveyor of Lloyds, in his interesting paper, read in July, 1886, before the Institution of Naval Architects : " Two large passenger steamers, of over 4,500 gross tonnage, having engines of about 6,000 indicated horse-power, built of the same dimensions, from the same lines, with similar propellers, are exactly alike in every respect, except so far as their machinery is concerned.

One vessel is fitted with triple expansion engines, working at a pressure of 145 pounds per square inch; while the other vessel is fitted with ordinary compound engines, working at a pressure of 90 pounds per square inch.

Both vessels are engaged in the same trade and steam at the same rate of speed, viz., 12 knots an hour. The latter vessel in a round voyage of 84 days burns 1,200 tons more coal than the former."

Since the year 1879 the following great ships have been placed upon the Liverpool and New York lines. " Taking them in the order of their fastest passage, out or home, they stand thus :" (Note 537-A)

Transatlantic Liverpool to New York in Days, Hours, Minutes:

- Etruria 6, 5, 31

- Umbria (sister ship) slightly longer

- Oregon 6, 10, 35

- America 6, 13, 44

- City of Rome 6, 18, 0

- Alaska 6, 18, 37

- Servia 6, 23, 55

- Aurania 7, 1, 1

The time has thus been shortened much more than half since 1840, and has been lessened forty per cent. since 1860.

In addition to the great ships mentioned, there have been placed upon the line from Bremen to New York, touching at Southampton, England, the eight new or lately built ships of the North German Lloyd, which form altogether the most compact and uniform fleet upon the Atlantic.

Their three last ships, the Trave, Saale, and Aller, are marvels of splendor and comfort, ranking in speed and power very little short of the fastest of the Liverpool ships.

They, as were the others of the company's eight " express " steamers, were built by the great firm of John Elder & Co., of Glasgow, their machinery being designed by Mr. Bryce-Douglas, to whose genius is also due that of the Etruria and Umbria, the Oregon, Arizona, and Alaska.

That of the Trave, Saale, and Aller, however, is triple expansion (page 531), these being the only ships of the great European lines of this character, besides the new Gascogne, Bourgogne, and Champagne (their equals in speed and equipment), of the French Compagnie Transatlantique, which were built in France, and which reflect so much honor upon the French builders.

All these steamers are of steel, with cellular bottoms carefully subdivided, and fitted with a luxury and comfort quite unknown thirty years ago —with more space, better ventilation, and better lighting.

It will be difficult to go beyond them until a further change is accepted to twin screws. That this change will soon come is pretty sure. It will hardly be possible to extend the power with a single screw beyond that of the 14,000 horse-power already in the Umbria and Etruria; with twin screws, however, it may be carried much beyond.

Their adoption would mean greater accommodation and comfort and less racing of the machinery at sea, but, above all, it would mean greater safety. Under present circumstances a complete break-down of the machinery of these great ships is a disaster which may entail delay as the least of the difficulties.

No sail-power can be given them which would serve to carry them into port; they must lie helpless logs in the water until fortunate enough to find a friend to tow them.

It is scarcely possible that both the engines of a twin-screw steamer should be seriously injured at the same time, so that arrival would be only slightly delayed in case of damage to the one set of machinery.

In fact, such a ship as proposed by Mr. John in his paper, referred to above, would be two vessels in one, divided by a great longitudinal bulkhead from top to bottom; the boilers, engines, and all the appurtenances of the one side being wholly independent of the other.

The discussion now going on may soon turn to action, and we may, I think, confidently expect the advent shortly of new ships far surpassing any yet built. The project of one great owner is a twin-screw vessel, of 550 feet length and 62 feet beam, to steam 20 knots, and to be so subdivided as to be practically unsinkable.

This would be 50 feet longer than the Etruria, and 5 feet broader. His ideal is one of much greater breadth, say 75 feet; but there is a difficulty in the way of docking a vessel of such extreme width.

That such a ship will pay as well as those now afloat can hardly be questioned. She will carry as much cargo, and with about the same expenditure of coal (being fitted with triple expansion engines), as the Etruria, and more passengers; and the owners may reckon in such a ship upon always having their full complement.

It is not only the timid who would prefer her; it is but commonsense on the part of anyone to choose that which will give them the greatest chances of safety, and of arrival within certain definite limits of time.

Nearly 60,000 Americans visit Europe yearly; nearly 16,000 foreign passengers (not emigrants) land at New York yearly, which one port also, in the governmental year ending June 30, 1886, received 50,412 of our returning countrymen.

As these numbers must be doubled to represent the whole movement to and fro, we have over 150,000 passengers (exclusive of emigrants) carried by the steamship lines between America and Europe in the fiscal year of 1885-86. It is needless to say that it is worth while on the part of any owner to offer special inducements in a traffic of such magnitude.

It has been impossible, of course, in a magazine article, to do more than touch upon the vast changes, and their causes, which have had place in this great factor of human progress. Higher pressures and greater expansions; condensation of the exhaust steam, and its return to the boiler without the new admixture of sea-water, and the consequent necessity of frequent blowing off, which comparatively but a few years ago was so common; a better form of screw; the extensive use of steel in machinery, by which parts have been lightened, and by the use of which higher boiler-pressures are made possible—these are the main steps.

But in addition to steel, high pressures, and the several other elements named which have gone to make up this progress, there was another cause in the work chiefly done by Mr. W. Froude, to be specially noticed as being that which has done more than the work of any other man to determine the most suitable forms for ships, and to establish the principles governing resistance.

The ship-designer has, by this work, been put upon comparatively firm ground, instead of having a mental footing as unstable, almost, as the element in which his ships are destined to float.

It is not possible to go below the surface of such a subject in a popular paper, and it must suffice to speak of Mr. Froude's deductions, in which he divides the resistances met by ships into two principal parts: the surface or skin friction, and the wave-making resistance (which latter has no existence in the case of a totally submerged body—only begins to exist when the body is near the surface, and has its full effect when the body is only partially submerged).

He shows that the surface friction constitutes almost the whole resistance at moderate speeds, and a very great percentage at all speeds; that the immersed midship section area which formerly weighed so much in the minds of naval architects was of much less importance than was supposed, and that ships must have a length corresponding in a degree to the length of wave produced by the speed at which they are to be driven.

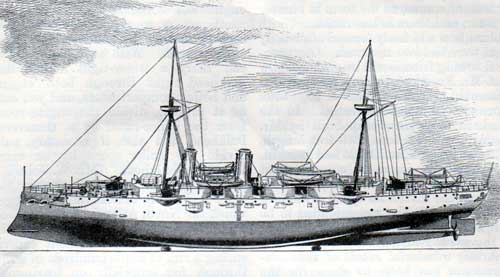

The Belted Cruiser Orlando, with Twin Screws.

He shows that at high speeds waves of two different characters are produced : the one class largest at the bow, which separate from the ship, decreasing in successive undulations without afterward affecting her progress; the other, those in which the wave-crests are at right angles to the ship's course, and the positions of these crests have a very telling effect upon the resistance.