The Ethics of Ocean Travel by Earl Mayo (1904)

Just at the present season when the great Atlantic liners are crowded to their capacity, and the European cities and resorts are thronged with visitors from this side of the water, the questions that arise in connection with an ocean voyage are occupying the minds of thousands of Americans.

This is not a surprising condition, for there are a good many of these questions to be answered even in the case of a veteran voyager, and the whole subject is a pleasant one to contemplate. We have been told many times, and have had it proved for us by the rural debating societies, that the pleasures of anticipation are greater than those of realization.

Photo 01: The First Day Out - Writing Letters Home

If this is true in general a voyage over pleasant summer seas on a great modern liner must be the exception that proves the rule, for pleasant as are its anticipations, the realization is pleasanter still and ofttimes the memories lingering afterward are pleasantest of all.

Ocean steamship travel has been revolutionized within the past quarter century by the rapid growth in size and speed and luxury of the steamships themselves and perhaps even more by the great increase in the number of yearly voyagers to Europe.

Instead of being confined to those who have attained wealth and leisure, a trip to Europe has come within the reach of almost anyone who cares to take it; instead of being the crowning event of a lifetime it is regarded as one of the possibilities of the ordinary summer vacation, so that where such trips formerly occupied several months they are now compassed within as many weeks.

The professional man, wearied by close application to his work, the teacher tired out from monotonous wrestling with intellects that are refractory in the matter of budding, the business man who sees a chance to combine pleasure and profit in a foreign expedition and the collegian bent on putting the finishing touches on his education before settling down to work-a-day life, all form part of the throng that betakes itself Europe ward with the coming of mid-summer.

Photo 02: Combining Conversation With The Joys Of The Sea

Notwithstanding the great increase of ocean travel, the big liner is still. a world apart with its own standards, its own customs and one may even say its own code of ethics.

In addition to the problem of what to take and what to leave behind in the matter of luggage, what clothes to keep out fat the voyage and what to put away in the trunks for the hold, whether to have one's money changed before going aboard or after arrival on the other side, and a hundred and one others that arise to perplex the prospective voyager, there are other puzzling questions relating to one's relations with one's fellow travelers that are equally hard for the novice to decide.

Particularly is this the case with that yearly growing class of passengers represented by the woman who travels alone or accompanied only by companions of her own sex.

The woman traveling abroad without male escort was so much a rare avis as to be a negligible quantity a generation ago, or even more recently. To be sure there were women who crossed the Atlantic on their own responsibility in the days of our mothers, or even in those of our grandmothers, but in the infrequent cases when this happened the chances were ninety-nine out of a hundred that she was to be joined at the moment of landing by a husband, brother, or some other relative.

Photo 03: Nearing European Shores - Sending Telegrams Home

Now, however, all this is changed. We are living in the age and in the land of the new woman-not the freakish, faddish person designated by this title a few years ago, but the self-reliant, independent, resourceful woman whom we all know in greater or less numbers. To use the expressive term employed by our French cousins, woman has "arrived," in the United States of America at least. Moreover, she understands this fact quite well herself and does not hesitate to act upon it.

So it is that at the present time fully as many women as men cross the Atlantic in the course of a season and as a great many men go abroad unaccompanied it follows that the reverse of this proposition is equally true.

In fact, the number of women traveling alone increases with every year so that within a short time, from present indications, the women voyagers will be in a clear majority, as they already are on at least one ocean line.

Women who are both single and independent no longer deny themselves the delights of European travel because, voluntarily or involuntarily, they are without husbands or convenient male relatives to escort them.

There are many women, too, whose husbands, fathers or et ceteras are detained at home by business, but who have abundant means and leisure to taste the joys of foreign travel. Even society leaders do not find it necessary nowadays to be accompanied by their male protectors when they take a run over to Europe.

Photo 04: How Friendship Ripens On The Sea

A season or two ago the fact of the great increase in the number of women travelers received a peculiar illustration in the. case of one of the ships of the Atlantic Transport line.

On one of her voyages this vessel carried fifty-eight women and one man! Needless to say that later on the man became engaged to and married one of his fair fellow·voyagers. What earthly chance does one poor, unprotected man stand among a shipload of women?

Of course, this was a very exceptional disproportion between the two sexes, such as is not likely to be repeated, but it is a fact that on the ships of this line there are often more women than men. In fact, it has come to be known as "the woman's line" among steamship authorities from the popularity it enjoys with women travelers.

This is due in large measure no doubt to the fact that as these ships carry only first·cabin passengers, and not a large number of these, the officers have more time to devote to little attentions of courtesy and assistance which women especially appreciate.

In part, too, it may come from the fact that the ships of this line are exceptionally big and steady and consequently mal de mer. the dread of many a woman voyager, is less to be feared on them than on some of the swifter ocean greyhounds.

Since these petticoated travelers are nearly all up-to-date American women it would be presumptuous to assume that they need to be told how to conduct themselves or how to take care of themselves. Still, if they are novices in the art of steamship travel, they make mistakes or deprive themselves of much innocent enjoyment through lack of familiarity with the code that prevails on shipboard.

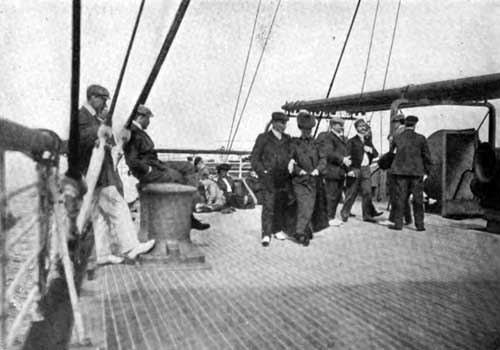

Photo 05: Promenading On Deck - The Favorite Pastime

In general it may be said that conventionality rules less rigorously on the deck of an ocean liner than in most public gathering places ashore. For instance, in a hotel dining room a gentleman would hardly presume, without previous acquaintance, to address a woman who happened to be seated at the same table.

But it would obviously be foolish to refrain from conversation with one's table neighbor in the saloon of an ocean liner where the same situation is to be repeated at every meal for seven or eight days.

To be sure custom may differ ashore in this very matter in different parts of the country. In the Western States, for instance, it would not be thought at all outre for two strangers who happen to be placed vis·a·vis or in adjoining chairs in a railway car to engage in conversation, even though they represent opposite sexes, but in the more effete and conventional East it would be looked upon as decidedly bad form, to apply its gentlest name, except under very unusual circumstances.

On ocean liners, however, a good many acquaintances are "scraped" in the course of every voyage without any loss either in their own respect or in that of their fellow travelers on the part of the scrapers.

The woman traveling alone is under no necessity of preserving a clam-like isolation providing she observes the amenities as thoroughly as she would in her own home. Of course, she will keep her intercourse with persons of whom she can know nothing except that they are entertaining and gentlemanly on the plane of distant if cordial acquaintanceship.

If she is a wise woman she will preserve a proper equation by finding at least a part of her new acquaintances among the women on board and will not confine them entirely to those of the opposite gender.

Under no consideration will the woman traveling alone allow bon camaraderie to degenerate into even a mild form of flirtation. Shipboard flirtations are not for the unchaperoned. Gossip hath many eyes and ears and a multiplicity of tongues, and there are many idle hands ready to do mischief even on an ocean liner.

Besides, one never can be quite sure, you know. The most gentlemanly passenger aboard may prove to be a professional gambler and the man of pious mien and clerical garb may have an unsavory reputation ashore.

But, with these considerations aside, the woman traveler may meet many pleasant persons in the course of her ocean crossing, and in this way make the otherwise tedious hours move quickly, even though she does not know one of the multitude of names on the passenger list when she steps aboard.

If she is a person of tact she is pretty certain to gravitate without much effort into a congenial group before the voyage is many days old. The only person who need be lonely on an ocean voyage is the hopeless bore or the equally hopeless boor.

This possibility of making new friends, hearing new experiences, coming in touch with new points of view, is one of the delightful features of ocean travel. It is part of the democracy of the sea which is due in great part no doubt to the almost entire absence of special privileges on shipboard.

One passenger may have a more expensive stateroom than another, but in almost all other respects the richest and poorest among the first-cabin passengers are on an equal footing. The traveler is judged therefore not by his or her chattels or social pretensions, but by the truer standard of intelligence and good-fellowship.

It is as though the voyagers had met together and passed resolutions saying: "Here we are, all met on an equal footing. For these few days we shall all be weighed, not by what we own or claim to be, but by what we really are."

The traveler who approaches the ocean trip in this spirit is pretty certain to have a pleasant voyage.

One of the most convenient things about steamship acquaintances is the unwritten, but well-established, law that they need not be continued beyond the end of the voyage. Two or three may promenade the deck together day after day and still when they meet ashore bow distantly or not at all, though in reality it is seldom necessary or desirable to put such a strain upon natural politeness.

Still the possibility is one of the charms of an ocean trip and it brings together persons who otherwise might not meet. The lion and the lamb may often be seen consorting together to the mutual bene6t of both. On a recent voyage a noted bishop and a champion prize-fighter,returning with the laurels and ducats obtained in England, became close friends and were seen daily together. It is safe to say that each found the other interesting and gained much knowledge of how the "other half" lives.

It is really amusing sometimes when one contemplates these deep-water friendships from the vantage point of a position ashore. These friendships, so dear, so pleasant, so brief! After the third day out we feel as though we had known each other all our lives, and yet only about one friendship in a thousand passes the customs inspector.

The woman traveler will make a serious mistake if she burdens her cabin trunks with an elaborate wardrobe and makes a display of her gowns. Commonsense comfort is the only rule of dress that holds on shipboard. Even the society stars who go abroad with twenty or thirty trunks allow the glories of their millinery creations to remain behind the locks of these trunks and wear only the simplest, most comfortable and most inconspicuous garments while at sea.

Aside from the fact that salt air is not good for 6ne garments custom has wisely decreed that it shall be so. The woman who makes a display of gowns on an ocean steamship reveals either ignorance or bad taste--and ignorance is bad taste. A single modest dinner gown, a walking skirt and two or three shirt waists. a pair of common-sense, rubber-soled shoes for walking on deck, a severely plain hat or tam-o'-shanter and plenty of warm wraps are the outer essentials of the wardrobe for an ocean voyage.

Once she has set foot on foreign soil, however, our woman traveler must not forget that shipboard unconventionality is at an end. She cannot act too circumspectly if she would avoid annoyance. She cannot walk about alone in European cities in the evening. In fact, if she goes out without a companion at any hour of the day a cab or bus is better than the sidewalk.

Europeans in general and in particular continental Europeans have not been educated up to the idea of a woman's right to travel about alone and many American women abroad have been subjected to serious embarrassment from the inability of Europeans to appreciate or understand the freedom of movement which the women of the United States enjoy at home.

Mayo, Earl, "The Ethics of Ocean Travel." In The Era Magazine, Volume XIV, No. 3, September 1904, P 238-242.