Early Steamships - 1887

Three years before (in 1836), a Swede, whose name was destined to become much more famous in our own land, had successfully shown the practicability of screw propulsion, in the Francis B. Ogden, on the Thames.

"She was 45 feet long and 8 feet wide, drawing 2 feet 3 inches of water. In this vessel he fitted his engine and two propellers, each of 5 feet 3 inches diameter " (Lindsay).

She made ten miles an hour, and showed her capabilities by towing a large packet-ship at good speed. There was no question of the success of this little vessel, which was witnessed on one occasion by several of the lords of the admiralty. Notwithstanding her unqualified success, Ericsson had no support in England.

It happened, however, that Commodore Stockton, of our navy, was then in London; and witnessing a trial of the Ogden, ordered two small boats of him. One, the Robert F. Stockton, was built in 1838, of iron, by Laird-63 feet 5 inches in length, 10 feet in breadth, and 7 feet in depth.

She was taken—April, 1839— under sail, to the United States by a crew of a master and four men. This little vessel was the forerunner of the famous Princeton, built after the designs of Ericsson, who had been induced by Commodore Stockton to come to America as offering a more kindly field for his talents.

In the same year with Ericsson's trial of the Ogden, Mr. Thomas Pettit Smith took out a patent for a screw; and it was by the company formed by Smith that the screw propeller was first tried on a large scale, in the Archimedes, of 237 tons, in 1839.

Of course the names mentioned by no means exhaust the list of claimants to this great invention. Nor can it be said to have been invented by either of these two, but they were the first to score decisive successes and convince the world of its practicability.

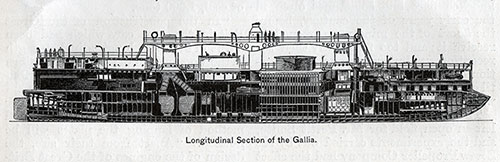

Longitudinal Section of the Gallia.

In 1770, Watt wrote to Dr. Smalls (who, a Scot, was at one time a professor at William and Mary College, in Virginia, but returned to England in 1785) regarding the latter's experiments in relation to canal navigation, asking him, "Have you ever considered a spiral oar for that purpose, or are you for two wheels ? " In the letter is the sketch, a facsimile of which is here shown.

Dr. Smalls answers that, "I have tried models of spiral oars, and have found them all inferior to oars of either of the other forms " (Muirhead's " Life of Watt," p. 203).

The general slowness with which men in the early part of the century received the idea of the mighty changes impending may be recognized when we look over the few publications connected with navigation then published. Mind seemed to move more slowly in those days; communication was tedious and difficult.

Edinburgh was as far from London in length of time taken for the journey as is now New York from New Orleans; few papers were published; there were no scientific journals of value; no great associations of men given to meeting and discussing scientific questions excepting the few ponderous societies which dealt more in abstract questions than in the daily advances of the mechanical world.

It was thus that the steam vessel came slowly to the front, and that it took more than a third of the whole time which has elapsed since Fulton's successful effort to convince men that it might be possible to carry on traffic by steam across the Atlantic.

Dr. Lardner is almost chiefly remembered by his famous unwillingness to grant the possibility of steaming directly from Liverpool to New York; and by his remark, "As to the project, however, which was announced in the newspapers, of making the voyage directly from New York to Liverpool, it was, he had no hesitation in saying, perfectly chimerical, and that they might as well talk of making a voyage from New York or Liverpool to the moon." (Note 519-A)

The Great Britain.

He strongly urged dividing the transit by using Ireland as one of the intermediate steps, and going thence to Newfoundland. He curiously limited the size of ships which might be used, and their coal-carrying powers.

Though a philosopher, he did not seem to grasp that if the steamship had grown to what it was in 1835 from the small beginnings of 1807 it might grow even more, and its machinery be subject to development in later times as it had been in the earlier.

Lardner seems to have typified the general state of mind when in 1836 the Great Western Steamship Company was formed, from which really dates transatlantic traffic.

A slight retrospect is necessary to enable us to understand the status of steam at the time. Little really bad been done beyond the establishment of coast, river, and lake navigation in the United States and coastwise traffic in Great Britain; a few small vessels had been built for the British navy.

In 1825 the Enterprise (122 feet length of keel and 27 feet beam) had gone to Calcutta from London in 113 days, 10 of which had been spent in stoppages; and steam mail communication with India was about being definitely established when the keel of the Great Western was laid. Up to this time America had undergone much the greater development, both in number of steam vessels and tonnage.

In 1829 our enrolled tonnage was 54,037 tons, or rather more than twice that of the United Kingdom. Charleston and Savannah had regular steam communication with our northern ports.

A few years later, in 1838, returns show that the former had 14 steamers, the largest being of 466 tons; Philadelphia had 11, the largest being of 563 tons; New York had 77, of which 39 were of a large class, exceeding generally 300 tons — the largest was the President, of 615 tons, built in 1829.

Liverpool had at this date 41 steamers; the largest was of 559 tons, 4 others exceeded 200 tons, and all the others were much smaller.

London had 169, of which the largest was the British Queen, just built, of 1,053 tons; the next largest was of 497 tons. Glasgow and Belfast had been in regular steam communication since 1818; Glasgow and Liverpool, London and Leith, since 1822. The first ferry-boat on the Mersey, it may be noted, the Etna, 63 feet long, with a paddle-wheel in the centre, began her trips in 1816.

In 1819 the Atlantic was first crossed by a ship using steam. This was the Savannah, of 380 tons, launched at Corlear's Hook, New York, August 22, 1818. (Note 520-A)

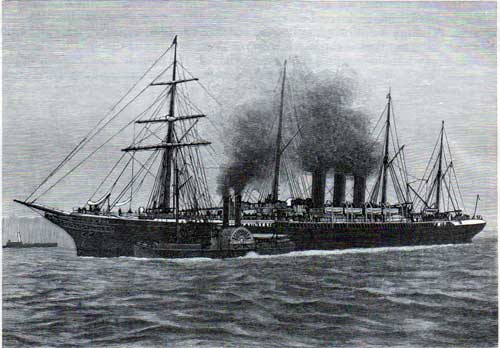

The City of Rome.

She was built to ply between New York and Savannah as a sailing-packet. She was, however, purchased by Savannah merchants and fitted with steam machinery, the paddle-wheels being constructed to fold up and be laid upon the deck when not in use, her shaft also having a joint for that purpose.

She left Savannah on the 26th of May, and reached Liverpool in 25 days, using steam 18 days. The log-book, still preserved, notes several times taking the wheels in on deck in thirty minutes.

In August she left Liverpool for Cronstadt. An effort was made to sell her to Russia, which failed. She sailed for Savannah, touching at Copenhagen and Arendal, and arrived in 53 days.

Her machinery later was taken out, and she resumed her original character as a sailing-packet, and ended her days by being wrecked on the south coast of Long Island.

But steam power had by 1830 grown large enough to strike out more boldly. The Savannah's effort was an attempt in which steam was only an auxiliary, and one, too, of a not very powerful kind.

Our coastwise steamers, as well as those employed in Great Britain, as also the voyage of the Enterprise to Calcutta in 1825 (though she took 113 days in doing it), had settled the possibility of the use of steam at sea, and the question had now become whether a ship could be built to cross the Atlantic depending entirely on her steam power.

It had become wholly a question of fuel consumption. The Savannah, it may be said, used pitch-pine on her outward voyage, and wood was for a very long time the chief fuel for steaming purposes in America.

How very important this question was will be understood when it is known that Mr. McGregor Laird, the founder of the Birkenhead firm, in 1834, laid before the committee of the House of Commons, on steam navigation to India, the following estimate of coal consumption :

| Under 120 horsepower | 10 1/2 lbs. per h.p |

| 160 horsepower | 9 1/2 lbs. per h.p |

| 200 horsepower | 8 1/2 lbs. per h.p |

| 240 horsepower | 8 lbs. per h.p |

Or more than four times what is consumed today in moderately economical ships. In other words, to steam at her present rate across the Atlantic the Umbria would need to start with something like 6,000 tons of coal on board were her consumption per indicated horse-power equal to that of the best sea practice of that date, which could hardly have been under 6 pounds per indicated horse-power per hour.

This may be said to have been the status of affairs when, in 1836, under the influence of Brunel's bold genius, the Great Western Steamship Company was founded as an off-shoot of the Great Western Railway, whose terminus was then Bristol. Brunel wished to know why the line should not extend itself to New York, and the result of his suggestion was the formation of the steamship company and the laying down at Bristol of their first ship, the Great Western.

Brunel's large ideas were shown in this ship, though in comparatively a less degree, as well as in his later ones.

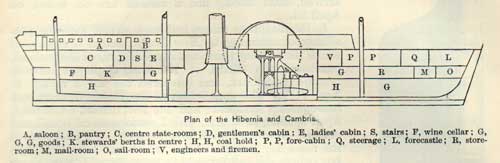

Plan of the Hibernia and Cambria.

A, saloon; B, pantry; C, centre state-rooms; D, gentlemen's cabin; E, ladies' cabin; S, stairs; F, wine cellar; G, G, G, goods; K. stewards' berths in centre; H, H, coal hold; F, P, fore-cabin; Q,; L, forecastle; R, storeroom; M, mail-room; 0, sail-room; V, engineers and firemen.

She was of unprecedented size, determined on by Brunel as being necessary for the requisite power and coal-carrying capacity.

The following were her principal dimensions :

- Length over all, 236 ft.;

- length between perpendiculars, 212 ft.;

- length of keel, 205 ft.;

- breadth, 35 ft. 4 in.;

- depth of hold, 23 ft. 2 in.;

- draught of water, 16 ft. 8 in.;

- length of engine-room, 72 ft.;

- tonnage by measurement, 1,340 tons;

- displacement at load-draught, 2,300 tons.

Dimensions of engines :

- Diameter of cylinders, 73 1/2 in.;

- length of stroke, 7 ft.;

- weight of engines, wheels, etc., 310 tons;

- number of boilers, 4;

- weight of boilers, 90 tons;

- weight of water in boilers, 80 tons;

- diameter of wheel, 28 ft., 9 in.;

- width of floats, 10 ft.

Her engines (side-lever) were built by the great firm of Maudslay & Field, who had been for some time one of the most notable marine-engine building firms of the period in Great Britain. They had, up to 1836, built 66 engines for steamers; the first being in 1815, when they built those of the Richmond, of 17 horsepower. The indicated power of the Great Western was 750; and a notable measure of the stride which steam has taken in the half-century since they undertook this contract is that today they have in construction twin-screw engines from which they have guaranteed to produce 19,500 horse-power, but from which they expect to obtain 24,000. These are to drive a great armor-clad, which has six times the displacement of the Great Western and will have twice her ordinary speed.