First-Hand Account of Steerage Conditions - 1898

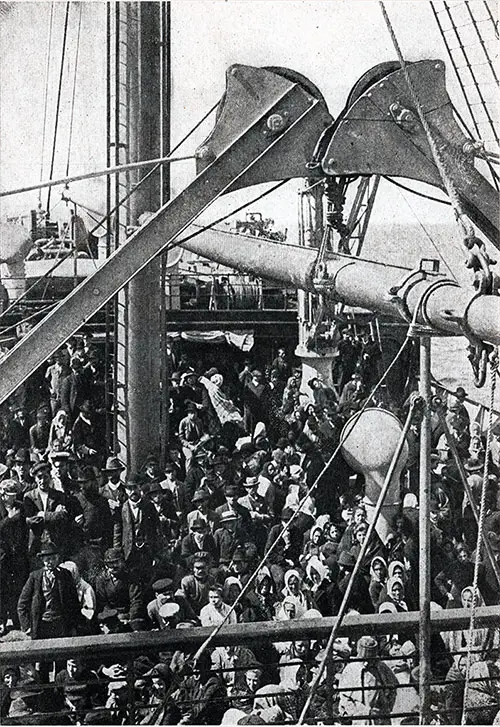

Steerage Passengers On Deck of Ocean Liner as Seen by a Lady of the First Cabin. The Fellowship of the Steerage Makes Good Comrades, Where no Barriers Exist and Introductions are Neither Possible nor Necessary. From Stereograph. Copyright © 1905 by Underwood & Underwood, NY. GGA Image ID # 146b639daa

Preface

Mr. H. P. Whitmarsh has made good journalistic capital out of his personal experience in the steerage. He contributes an article on "The Steerage of Today," which tells from the inside of the accommodations and scenes of the emigrant portions of our great liners, as witnessed by him in a trip during 1897.

It's a personal graphic narrative of the experience had by Mr. Whitmarsh who came over as No. 1616, Group C. Castaigne's sketches illustrate the reality of his 1897 voyage. This article of great social interest with numerous pictures depicts the struggles of the immigrant on this journey and at the time of landing.

This First-Hand account records a journey on a typical transatlantic steamship in 1897 as a passenger in steerage. Harsh by modern standards, this was typical of many ships that brought immigrants to the United States in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The Journey Begins

"Trunks in the for'ard van, sir," said the porter, touching his cap.

" Thank you," I said, feeling for some coppers. " Do I change anywhere?"

" No, sir; 'e goos right through to Birken'ead, sir. Thank 'e, sir. Ool 'e 'ave winder oop, sir ? "

" No; I think it 's too warm," I answered.

" Ees, sir; it be proper 'ot to-daay, an' no mistaake. If this yer weather 'olds, 'e 'll 'ave a fine v'yage, sir."

I hope so," I replied, smiling at the man's observation, and wondering whether he would be so polite if he knew I was traveling on an emigrant's reduced-fare ticket. I had almost made up my mind to test him, when the guard's whistle blew, and the train slowly moved out of the station, with a vigorous slamming of doors along its length.

As, fortunately, I had the carriage to myself, I threw my feet up on the seat, pulled out my traveling-cap and a book, and settled down comfortably to read. But it was no use. My mind was too busy speculating upon the trip I was about to make.

Two weeks before I had written to a steamship line in Liverpool to secure a steerage passage for New York, and I was not more than ordinarily happy at the prospect.

In reply to my application, there came a request for a deposit of one pound, and a blank form reading as follows:

- Number.

- Name in full.

- Age.

- Sex.

- Married or single.

- Calling or occupation.

- Able to read and write.

- Nationality.

- Last residence.

- Seaport for landing in the United States.

- Final destination in the United States.

- Whether having a ticket to such destination. By whom was passage paid?

- Whether in possession of money. If so, whether more than $30 and how much, if less than $30.

- Whether ever before in the United States, and if so, when and where.

- Whether going to join a relative and if so, what relative—their name and address.

- Ever in prison, or almshouse, or supported by charity? If yes, state which.

- Whether a polygamist.

- Whether under contract, express or implied, to labor in the United States.

- Condition of health— mental and physical. Deformed or crippled—nature and cause.

After passing this preliminary examination to the steamship company's satisfaction, I received a ticket, with an order on the Great Western Railway, together with information when it was necessary for me to be aboard.

Taking the Train Across England to Liverpool

I must admit that from this time until I found myself on the six-o'clock express from Oxford to Liverpool I was not free from a certain "all-gone feeling" in the pit of my stomach; for the steerage, at a distance anyhow, has few charms. I was now, however, somewhat underway, and the gray old university town was rapidly vanishing.

It was midsummer, and through the long, delicious twilight I laid down my book and bade good-bye to the fair country of the Midlands. A flat landscape, but so green, so old, so full of beauty, that it is never tame.

Everywhere are square old Norman towers, rising like giant sentinels among the trees and thatched cottages of the villages. Everywhere are smock-frocked rustics, some working in their gardens, others strolling with their lasses along the winding byways of the fields, halting at the stiles and making love.

And everywhere are slow, brimming rivers and canals, freighted with business and pleasure, and swaths of new-mown hay, and greenest hedgerows, and fields ablaze with scarlet poppies.

At Birmingham, a number of artisans entered the carriage and kept me amused with their broad dialect until, at half-past ten, we reached Birkenhead.

The Steerage Office in Liverpool

The following morning (Saturday) broke with a cloudless sky and a stiffish breeze from the westward. With regrets for the headwind, yet with lively anticipations of what the day might bring forth, I made my way down to the steamship office.

I found the steerage offices in the basement of a large stone building near the dock; and having descended a flight of steps and passed through a darksome tunnel; I emerged into a dimly lighted room, round two sides of which were seated some forty of my fellow-passengers to be.

Though it was nine o'clock, the agent had not yet arrived; and already a few of the women were working themselves into excitement.

In the middle of the room, striding up and down in a most impatient, disgusted way, was a tall, lean negro, dressed in the latest London fashion. He had lost his trunk and was furious at the railway company, the steamship management, and the country at large.

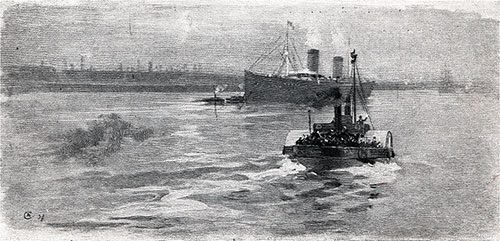

Immigrants at the Landing Stage, Liverpool. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 1458dfdf94

The cheerless people on the seats paid little attention to his harangue, but sat, for the most part, dumb and patient, wrapped in their own somber thoughts. All were natives of the British Isles and wore a weary, resigned look on their faces.

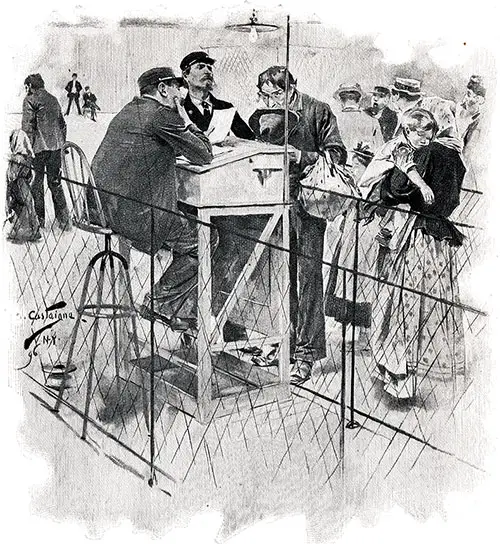

On the appearance of the agent, perhaps half an hour afterward, came the rush to make final payment. All those going to the Eastern States had their tickets so stamped; for in such cases the steamship rate includes railroad fare to destination.

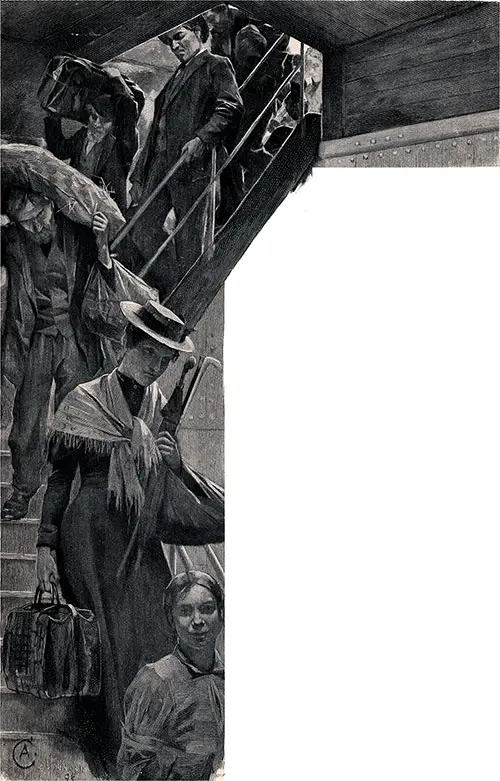

The Stairway to Steerage - Between Decks. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 1458e70392

At the Landing Stage in Liverpool

At this point I lost my identity and became No. 1616, group C. With this stamped upon my passage-ticket and inspection-card, I was taken in charge by an officer of the company, and led down, with the rest, to the landing-stage, where the tender awaited us.

Here we found a large number of other emigrants, principally Scandinavians, who had come through other channels than the Liverpool office.

After a tiresome wait of more than an hour, during which time further batches of foreigners continually increased our company, we got away, and puffed up-river, where our steamer lay at anchor.

There were now more than three hundred of us. No attempt at acquaintanceship was made as yet. All sat stiff and distant, hugging their numerous bundles in a most uncomfortable fashion, and staring coldly into one another's faces.

Opposite me sat a dark, thick-set Welshman, with his wife, a thin, chinless woman, and five small children, the eldest eight years old. Pretty, dark-eyed little tots they were, but oh, how dirty! Even at that stage of the journey, a high-water mark was plainly visible.

On my left were two Irishmen, one old and beery, the other a strapping young fellow with clean-cut features and a roguish blue eye. He was from Tyrone, I learned afterward. Close on my right huddled a family of Finns—the man tall and gaunt, with high cheek-bones and expressionless face; the woman of a heavy, bony type, yet comely and scrupulously clean.

Taking the Tender to the Ocean Liner

A gay kerchief confined her hair and was tied under the chin, and a white-haired baby slept in the shawl at her back. There were also two shy, pale boys with the same white hair, and black conical caps surmounting it.

A little beyond stood a group of Germans, two women and a man, all pale, fat, flabby, and talkative. Amidships, perched on the trunk he had lost, and swaying to and fro with closed eyes, sat my friend the darky, drunk.

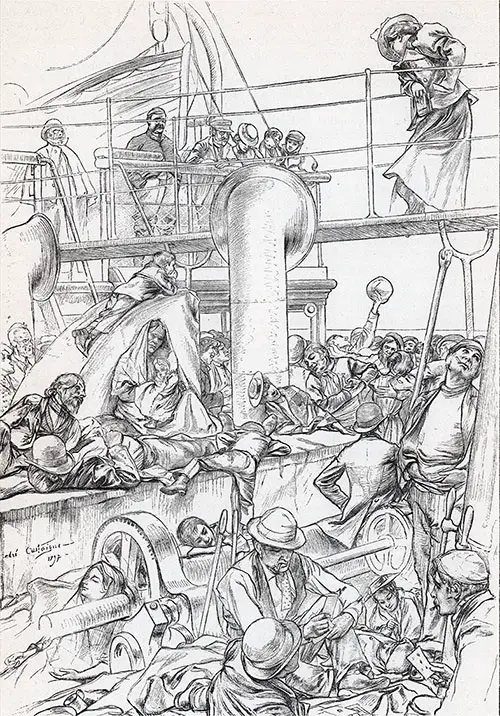

Within half an hour the paddle-wheels of the tender stopped, and we scrambled on deck, to find ourselves nearing the vessel that was to be our home for the following week.

A sheer twenty feet of black bulwark, as long as a village street, and studded with rows of port-holes, rose before us. Above it ran a double tier of white deck-houses, carrying a still higher bridge, and capped by two monster funnels.

We caught a glimpse of white boats hanging in the davits, red-mouthed ventilators, the brightest of brass-work, the blue-peter fluttering at the fore, and suddenly we were alongside. Then the bugle sounded, a small army of stewards lined up to receive us, the gang-plank was lowered, and we filed aboard.

Boarding the Steamship for the Trip Across the Atlantic

"Second cabin, sir?" said the master-at-arms by the gangway.

"No; steerage," I replied.

His polite tone changed, and he invited me to " Step for'ard lively!" in a manner that left no doubt in my mind as to what part of the ship I belonged. But already the narrow passage between the deck-house and the bulwark was blocked.

Those in the lead were unable to get below quickly enough; and in spite of being driven, pushed, and sworn at, we stuck there in a compact mass until two deck-hands were sent charging through the crowd to show the way round to the other side of the deck.

"Is ut cyattle we are, that we 're tr'ated this way?" indignantly asked a middle-aged Irishman who was trying to keep his wife and children from being crushed.

No; if we was cattle we 'd be all right," answered a man beside him. a There 's a fine if a beast is landed with a broken leg; but if our legs or necks is broke, it 's our own lookout. I 'm a cattle-man, and I know."

By degrees, my bag and I were edged forward and directed down a steep flight of stairs. A steward at the foot allotted me a bunk, into which I threw my things with a sigh of weariness and relief.

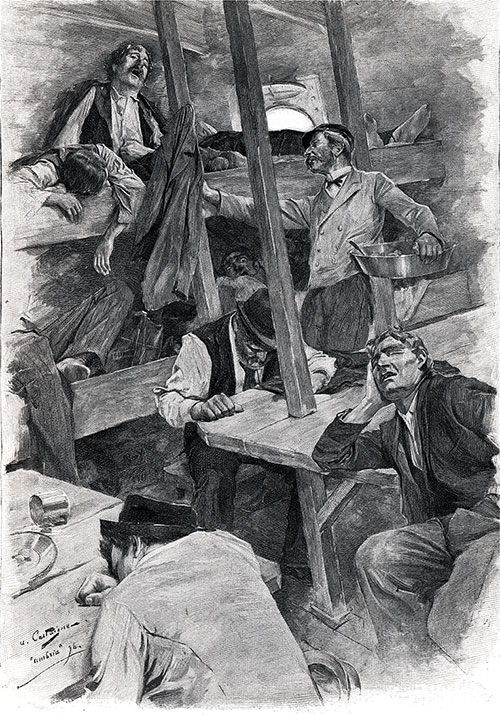

My First Observations of the Steerage

Steerage No. 1 is virtually in the eyes of the vessel, and runs clear across from one side to the other, without a partition. It is lighted entirely by port-holes, under which, fixed to the stringers, are narrow tables with benches before them.

The remaining space is filled with iron bunks, row after row, tier upon tier, all running fore and aft in double banks. A thin iron rod is all that separates one sleeper from another.

In each bunk are placed a donkey's breakfast (a straw mattress), a blanket of the horse variety, a battered tin plate and pannikin, a knife, a fork, and a spoon. This completes the emigrant's " kit," which in former days had to be found by himself.

This steerage, with a capacity of 118, was kept solely for English-speaking males. Directly below it was steerage No. 2, of similar size, intended for foreign males.

A little farther aft was steerage No. 3, with accommodations for 172 sleepers. Abaft on the port side, two flights take one down to the "married quarters."

The single females are stowed in pockets on both sides of the ship. These, in distinction from the men's quarters, are divided into rooms holding from four to sixteen persons, and have a common room for meals.

To the credit of the ship, it must be said that everything was clean. Sweet it was not. Spotless, sanded decks, scrubbed paint-work, and iron bunks could not hide the sour, shippy, reminiscent odor that hung about the steerages, one and all.

The Tender Filled with Immigrants is Nearing the Vessel. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 1459193d41

In the half-light of the great 'tween-decks, my companions were busy establishing themselves. As many of them evidently carried all they possessed in their hands, the bunks were soon piled with a strange assortment.

Carpet-bags, brown-paper parcels, cooked victuals, underclothing, fruit, bird-cages, and several loud-smelling, suspicious-looking bottles, were frequently seen.

Strange to say, nearly everyone seemed to be provided with a specific for seasickness. One man had apples, another a patent medicine, a third carried a pocketful of lime-drops, and yet another had pinned his faith upon raw onions.

It may perhaps be interesting to intending voyagers to know that not one of these preventives had the slightest effect. I was an unwilling witness of their non-efficacy afterward.

Kneeling in an upper bunk near me, a middle-aged Irishman was hanging a pot containing a shamrock plant. I entered into conversation with him and learned that he was going to join his son in California, to whom he was taking the shamrock as a present.

Immigrants On the Steerage Deck. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 14595ada32

"I hope it will live," he said, looking wistfully at the pot as it swung from the beam. "'T was the wan thing the bhoy wanted. ( L'ave iv'rything," says he in his letther, " an' come over.

I have enough for the both of us now," says he; ( an' I can make you comfortable for the rest av your days. But," says he, " fetch me a livin' root av shamrock if ye can.) "

Returning on deck, I waited until I saw my trunk hoisted inboard from the baggage-boat, and then, with an easy mind, I set about to see what deck-room was bestowed upon us.

Except for the square about the after hatch, we were undercover, and our perambulations were confined to the narrow space on each side of the deckhouse, along which ran a narrow, comfortless seat.

Limited enough, in all conscience, then; but more so when, on the following day, half of it was roped off to keep us from going too near the saloon passengers' windows.

The whole upper and hurricane decks were reserved for our more fortunate shipmates, and so well was every means of access guarded that, with one exception, I had no opportunity of seeing anything but our own part of the ship.

Inspection by the Surgeon

Before long a squad of stewards cleared the steerages and mustered us all for the doctor's inspection. Evidently, the doctor was in no hurry; for we stood crowded together, in the heat of that summer day, two mortal hours, waiting his pleasure.

Poor mothers! Poor babies! Tired, hot, and hungry (for no dinner had been served), the little ones cried incessantly, while the women complained in a high key, and twelve nationalities of men swore.

Here I made my first acquaintances, and it was curious to mark how, in such a gathering, a few of us that were perhaps more refined than the average were drawn together. United by a common bond of disgust for the whole proceedings, we forgot formality and talked to one another like rational beings.

Before we were released, three men took me into their confidence. Whence they hailed, whether they were bound, and why, were bits of the information they imparted on the slightest provocation, and they needed little encouragement to draw forth volumes of ancient history and future hopes.

This first inspection, indeed, seemed as though it were planned to introduce us all, and I came out of it on nodding acquaintance with a score.

At length, I slipped through the " drive " and stood before the doctor. He lifted the peak of my cap, looked me straight in the eyes, and passed me on; my tickets were then halved, quartered, and stamped at farther points, a detective scanned me sharply, and the ordeal was over.

The Ship is Finally Underway

The next thing of interest to us was the fact that the ship was moving. Attended by two puffing tug-boats, the great vessel was carefully threading her way down-stream to the landing-stage, where the saloon passengers were to be taken aboard.

Slowly the leviathan swung to the tide and tenderly laid her shapely side against the float. The gangway once more connected us with the shore; but we were roped well back from it, for fear some foolish one might at the last moment change his mind.

As soon as the stream of well-dressed men and women were aboard, then came the warning bell; the last link soon was withdrawn, and we edged crabwise from the pier.

The next instant the surging sea of faces that had been held in check till now rushed to the stage chains, and, amid a waving of hats, handkerchiefs, and umbrellas, raised a mighty cheer.

Although the steerage answered it with heart and soul, yet in its tone, I marked a difference from the happy, ringing cheer that carries a ship from an American port.

Ours was a cheer in name only—in truth, it was but a mouthful of noise made to choke back the cry that was forcing itself up in many a throat. For from America people go chiefly on pleasure; but with every ship that sails from England, how many there are who leave their friends forever!

One picture of that day stands out more strongly than all the rest. It is the picture of two women waving a last goodbye to some loved one aboard. I shall never forget the agonized expression that came over the younger one's face when the ship began to move.

Hiding her head on her companion's shoulder, she wept as though her heart would break. Then, suddenly calming herself, she lifted her brave little face, smiled through her tears, and waved us out of sight.

But now all partings had an end. A few preliminary revolutions of her screws, a pause to shape her course, and our ocean racer was speeding down the murky river. Down through that crowded thoroughfare of ships, she sped at a quick rate.

Out past the New Brighton pier, the bar, and northwest lightships, out into the cleaner water of the bay, until the twinkling sunset lights of the anchored fleet astern went out, and the flash of the skerries on the bow lighted her road to sea.

At eight o'clock Holyhead was on the beam, and we were reasonably out into the Irish Channel. The headwind and sea immediately became more evident, and our vessel went courtesying down toward Tuskar Rock Lighthouse in a way that quickly cleared her decks.

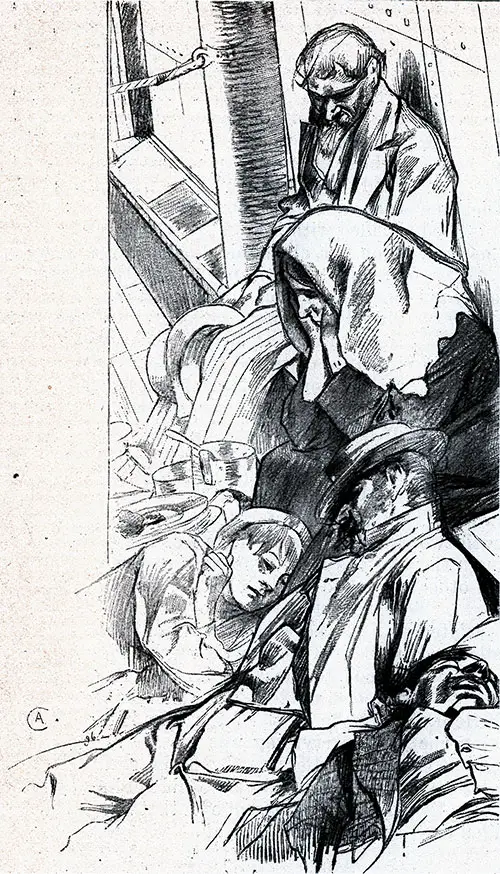

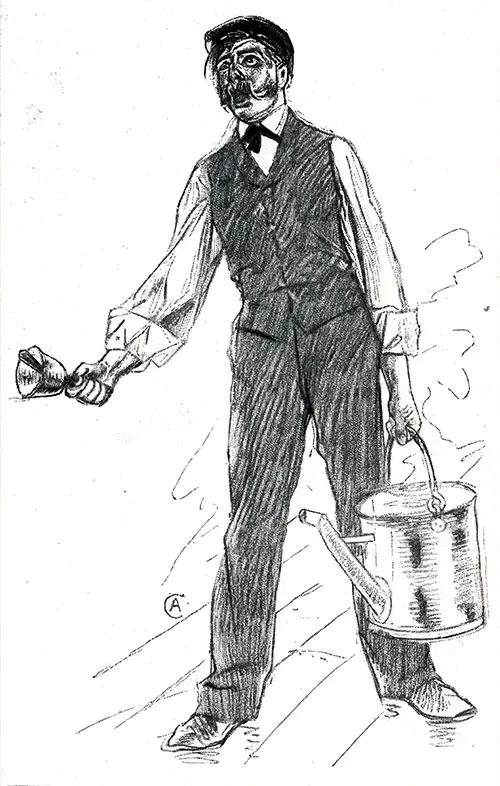

The Bawling Steward of the Steerage. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 1459848781

Night shut-in with an overcast sky, and a thin Channel fog rolling up from the southward. With the darkness, there fell a quiet upon the ship. It seemed as though every one slept, and the great vessel was thrashing her way down the Welsh coast by herself.

Already everything aboard was " shipshape and Bristol fashion "; already every part of the powerful mechanism was running with as much precision as though she had been out a month.

At four bells I went below. Except one group carousing, I found all " turned in." Few of them were asleep, however. About half sat propped up in their bunks, early victims to seasickness.

As our steerage was so far forward, the motion of the vessel was violent, and this, with the stifling atmosphere of the place, the stench, and the unearthly noises of the sick, nigh sent me back on deck again.

Rallying, however, I picked my way along a slippery aisle and reached my berth. It was a top one, thank Heaven, and the middle of a row of five. The other four bunks being tenanted, I had no means of entering my own but through the stanchions at the foot; and this I did with many a suspicious look at the prostrate forms on each side.

Take away the thin rods, which, after all, were almost as imaginary as the equator, and our row was merely a bed for five, with me in the middle.

A few of the men had taken their coats off and placed them under their heads for pillows; but most lay as they had stood, with boots, coats, and, in many cases, their caps on.

After building a barricade of bags and blankets on each side, I lay down in the middle, and got a few hours' sleep. One night of it, however, was sufficient. For the remainder of the passage, I slept on deck.

Calling at Queenstown (Cobh)

Next morning at four o'clock we called at Queenstown, where we took aboard the mails and some seventy more steerage passengers. The newcomers were principally fresh-looking Irish girls, who, in spite of the early hour, began to dance reels and to sing to the accompaniment of an accordion.

This waked up the other musicians aboard, and before long we had a flute, a tin whistle, and the accordion in full swing. Each instrument had a separate audience, who jigged, sang, or listened, according to the will of the performer.

All Sunday we were in smooth water, running under the lee of the Irish coast. The day being fine and warm, the steerage swarmed on deck in full force.

Men, women, and children all crowded about the after hatch, some playing cards, some dancing, and some already making love; but for the most part, they lay about the deck, sleeping and basking in the sun.

In the afternoon my friend the Irishman appeared with his shamrock. He wanted to give it a taste of fresh air, he said. At sight of it many of the Irish girls shed tears; then, seating themselves about the old man, they sang plaintive Irish melodies until the sun went down.

The sad faces of the homesick girls and the old father sitting among them holding in his lap the precious little bit of green presented a sight not readily to be forgotten.

Life in Steerage During Heavy Weather. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145a264916

About nine in the evening, having passed Fastnet, we encountered the Atlantic swell and its consequences. For the next two days, the weather smacked of the stormy Isles of Britain.

A keen northwesterner and a gray, lumpish sea, which broke continually over the starboard rail, drove us shivering to leeward, where the few of us who were blessed with good sea legs and stomachs passed the time spinning yarns and burning unlimited tobacco.

Although the weather could not in any sense be called rough, yet at the first pitch the bulk of the steerage went under, and there remained.

My chief friend at this time was a young man who hailed from Boston. After a two-years' voyage in an English merchantman, he had been paid off in Hamburg, and was making his way home by the most economical route. He was an intelligent, observing fellow, and we amused ourselves by studying the characters of the different persons about us, and guessing their occupations.

After we had guessed, we would enter into conversation with the subject of our speculation, and find out whether either of us was correct. Now it happened on the morning of the third day, while we were tramping up and down the lee side trying to keep warm, that we discovered a new woman —that is to say, one whom we had not seen before. She was standing with her back to us, looking out over the sea.

" There! " said my companion; a what do you think she is? "

I noted that the young woman wore a perky little hat, and was dressed better and with more taste than any I had seen in our quarters, and I hazarded that she was a dressmaker.

Pooh! " he replied. " I bet she 's a second-cabin passenger who has lost her way and strayed among the animals."

Well, how can we prove it? " said I. " I certainly am not going to interview the lady."

"Oh, I'll ask her," he answered. Upon this, I left him and walked aft. When I turned and looked forward again, he was standing beside her, talking. And from that time, except when he deigned to smoke a pipe with me after women's hours, my sailor friend was lost to me.

Steerage Passengers On Deck During Smooth Weather. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145a5034b8

I suppose there are no conditions more favorable to the rapid growth of acquaintance and friendship than those on shipboard. On the other hand, however, there is no place like it for wearing a friendship threadbare —for finding people out. Sea friendships, sea promises, and sea plans, I have noticed, are uncertain things at best, and never to be depended upon.

Away from conflicting elements and outside influences, unable to see the obstacles, the new roads, which alternately block and open up in the real journey, forgetful that each new day and face and circumstance swings him round in some new direction, the deep-sea traveler pricks off his future course with childlike faith and simplicity.

With the first whiff of land, however, his chart goes overboard, and his ways are henceforth governed by the winds and waves of chance. Knowing these things from previous experience, I watched with much interest the outcome of my Boston friend's entanglement.

Although I question whether any man was ever truly thankful for steerage fare, there comes a time in the experiences of most emigrants when they must eat something; and after three days of bottled stout and dry biscuits, I began to listen for the sound of the bell and the bawling steward who announced our meals.

The Meals in Steerage

At eight o'clock each morning we were served with oatmeal, coffee, soft bread, and butter. Every other morning Irish stew was added. For dinner, we received excellent soup, one kind of meat or fish, with potatoes and bread. Twice we had steamed pudding.

For supper, we contented ourselves with bread and butter and tea. I must say that the tea was remindful of chopped corn-brooms and that the coffee was an unadulterated abomination; but the remainder of the food was plain, wholesome fare, clean and of good quality.

The significant drawback was the way in which, to quote one of my friends, it was slung at you." The best of soup loses something of its savor when ladled out of something that looks alarmingly like a slop-bucket, and no meat is improved by being cut into junks and piled in a kid."

But then, what would you? What kind of transportation, with board and lodging threw in, can one expect for less than one cent per mile?

At nine each evening the night-watchman made his rounds, and sent all the females below. Poor man! I did not envy him his occupation. No sooner did he appear on one side of the deck than his charges would scurry round to the other side; and if by stratagem he cornered them, they would break and fly in all directions, taunting him the while. It invariably took him an hour to accomplish his task, and sometimes longer.

Getting Vaccinated

On Tuesday, our fourth day out, came the much-dreaded vaccination muster. Many and loud were the objections raised to the enactment of this law, and when No. 1 steerage lined up with bared arms for the doctor's inspection, a more sullen lot of men I never saw.

Those who had no marks, or whose marks were not sufficiently distinct, were vaccinated again. One man, an Irishman, made a stir by refusing to be operated upon, and insisting that the scar of a knife stab was a vaccination mark. When told that he could not enter America as he was, he submitted to the process.

From this time on the weather was fine, and the steerage, now thoroughly shaken together, and beginning to find its appetite, began to show itself in its true colors.

To me, the most noticeable thing about the life was the ease with which the yoke of civilization was thrown off. If conditions are favorable, I opine that a significant proportion of the steerage passengers throwback to their Darwinian ancestry about the third day out.

Away from home, country, and religious influences, unrestrained by custom and conventionality, bound by no laws of action, and separated from all that force of opinion so strong in the world ashore, they let themselves go, and allow their baser natures to run riot.

No sooner has the seasickness left them than they growl and snarl over their food like dogs, scrambling for the choice pieces, and running off to their bunks with them; they grow quarrelsome; their talk is lewd and insulting; brute strength is in the ascendant; and, without shame, both sexes show the animal side of their natures. But most apparent and obnoxious are the filthy habits into which many of them fall.

The sea seems utterly to demoralize them. Some of them will remain for days in their berths, where, without changing their clothes, they eat, sleep, and are sick with the utmost impartiality, and without the blessing of soap and water.

Hence the steerage as a whole, the married quarters " (where there were children) in particular, was ill-smelling and otherwise objectionable.

The Immigrants in Steerage

The four hundred and three souls aboard entered as emigrants were made up of the following nationalities:

- American - 59

- Bohemian - 1

- English - 51

- Finn - 43

- French - 1

- German - 7

- Irish - 113

- Norwegian - 25

- Russian - 1

- Scotch - 4

- Swedish - 77

- Welsh - 21

Of these, two-thirds were men, the majority over thirty years of age, and many with wives and families. Most of them were men of nervous dispositions or were failures going to start afresh and try their luck in the new country.

With few exceptions, they had friends in America from whom they expected help in one way or another. A goodly percentage of the Scandinavians were bound for the West, but by far the higher number of our steerage passengers were booked for the Eastern cities.

The type of emigrant as a whole was, to me, sadly disappointing; and I am forced to admit that the worst class on board our vessel at least were those who hailed from Great Britain.

While among the Scandinavians there was a goodly percentage of sturdy, honest farm-laborers and mechanics, it was very evident that those from the British Isles were adventurers, floaters, scum—a brotherhood, indeed, that needs no augmentation in this or any other country.

Among those aboard, we had a boilermaker from Birmingham, a little, thin, wiry fellow with a broad accent and a passion for the tin whistle. He was invariably to be found seated on the after hatch, playing ballads, or coaxing a step-dance out of the bystanders with a lively jig-tune.

The "little whistler," as we called him, was truly the sunshine of the steerage. To see him playing a reel, his face red and puffed, his foot beating time, and his arms and body working convulsively with the music was entertainment in itself. Unfortunately, he wet his own whistle too frequently, and as a result of his improvidence, all his money was gone before we reached New York. But it did not worry him.

My brother 'll be on th' dock to meet me," he said proudly; an' it 'll be all right. 'E 's a boss in Brooklyn, ye know, 'e is. See, 'ere 's 'is address. 'E told me, when 'e wrote, as ah could coom an' rest for a year if ah liked, an' ah 'm gooin'. Would n't you— eh ?

Then there was the red-faced man." He came from Nottingham and was the wealthy man of the steerage. Broad-shouldered, clean-shaven, tight-trousered, a typical British Boniface, he, his wife, and little girl were going to Pittsburg to open a saloon. It was the red-faced man's daughter who first called our attention to a becalmed sailing-vessel on the bow.

" Oh, look, papa!" she cried. Theer 's summat stickin' oop th' sea! "

There was also a dour-looking, long-legged Scotch farmer among us, who nightly set his back against the house, and argued on religion and English politics.

Steerage Passengers Get a Glimpse into Paradise. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145a6af2ad

Another character was an Irish old maid about seventy, thin, dreadfully wrinkled, and toothless, yet as careful of herself as a girl of sixteen. After her seasickness was over, she would sit outside the door of the female quarters, and croon us old Irish songs.

We all liked her, and many were the offers made by the young men to buy her little delicacies from the stewards; but she refused them all, saying that her nieces, to whom she was going, had warned her to mind herself, and beware of the " males."

Then, too, there was the bore," a sickly, pimple-faced lad from London. His conceit was colossal. He would corner you, and talk to you for hours about himself.

He was forever writing what he called s sentimental poetry, and reading it to you, and drawing " classical " heads, and asking you what you thought of his " young lady." Inside his waistcoat, he carried a greasy photograph of the fair one, which came out on all occasions.

Immigrants from Steerage in the Registry Department at Ellis Island. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145a8f38eb

The Irish servant-girl, of course, both before and after service, was much in evidence; and there were a few Swedes going out for the same purpose; besides farm-hands, miners, dock-laborers, a few artisans, and a Salvation Army sergeant.

As for the saloon and second-cabin passengers, we knew nothing of them. The steerage is a little world in itself, revolving in an orbit far apart from these more important planets.

Occasionally our singing would attract a few of the nabobs above, so that they looked over the rails, and threw down money and oranges and nuts. At such times the after hatch was like a huge bear-pit.

One evening several members of steerage No. 1 and I were grouped about the foremast, talking upon the all-absorbing subject, America. The conversation drifted into an argument on the equality of man, and this, in turn, led to a discussion as to the rights of the saloon passengers.

If we ain't got no right to go into their quarters," said one of the men, " wot right 'ave they to come into ours? It 'u'd be all right if they be'aved theirselves; but they don't, blast 'em!

Anybody 'd think as 'ow we was a lot of bloomin' lepers, to see the way they carries on— a-'oldin"and kerchiefs to their noses, an' a-droring their silk petticoats close to 'em, an' tiptoein' an' titterin'.

( Ho, George,) says the big woman with diamonds in 'er ears, as come down yesterday; ( the pore, bloomin' creechahs; but wot makes 'em smell so? ) Just as loud as that, mind you. S"elp me, I could 'a' tore 'er to pieces!"

As I happened to witness the incident so graphically described by the cockney, I could not help feeling that his anger was righteous.

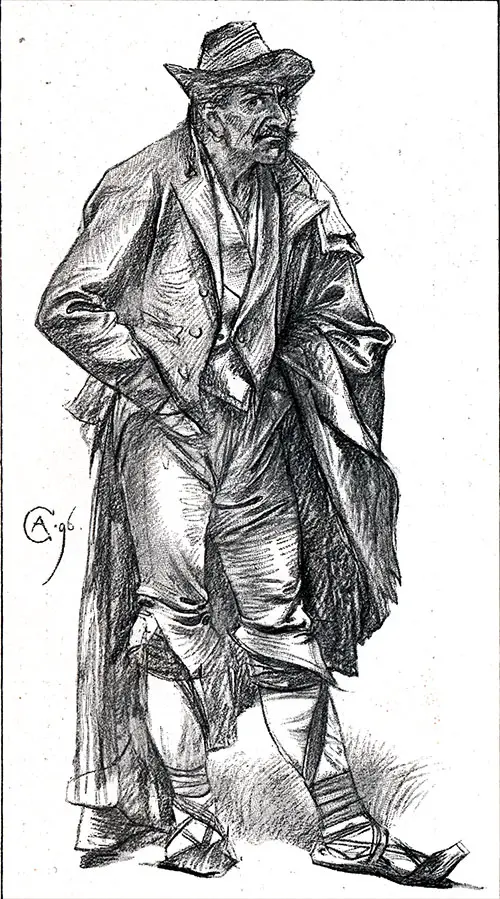

An Italian Type Immigrant from the Steerage. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145bb1d8d9

It soon became apparent that a number of the men were curious to behold the glories of the saloon, and it was at length proposed by one of them that we should visit the saloon deck that night.

Six of us having agreed to venture it, we waited until four bells (ten o'clock) had gone, and then, when the watchman was forward, climbed the barred ladder leading up from the after hatch, and reached that part of the upper deck allotted to the second cabin.

Here we paused and hid ourselves guiltily abaft the winches amidships. With the exception of a " clustering " couple leaning over the port rail, the deck was deserted. Looking forward past the second-cabin barrier, we could see the broad white deck reserved for the saloon passengers.

Rows of comfortable steamer-chairs were ranged against the house, and from a hundred brass-rimmed ports streamed lights suggestive of warmth and luxury.

Somewhere forward we could hear a piano playing and the sound of a woman's voice. It stopped, and there came a loud clapping of hands. Someone said there was a concert in the ladies' saloon. In the lull that followed we heard a cork pop in the smoking-room and caught a whiff of a good cigar.

Come on," whispered the Londoner, who had appointed himself leader. Another minute, and we had ducked under the dividing-line, and reached the open ports of the smoking-room.

For a few moments, we stood looking into the most handsome ship's smoking-room in the world. To us of the steerage, it was indeed a glimpse into paradise.

Our peep, however, was destined to be but a short one. Before we had time thoroughly to take in details, we were discovered by the watchman, and driven ignominiously back to our own pen.

Closing in on Land - The New World

Early Thursday morning, a buzz of excitement ran round the decks when it was known that the long narrow cloud that lay close upon the northern horizon was the smoke of a rival steamship.

The prospects of the race made food for talk during the day. Would she get in first, or had we time to pass her? The matter was not settled until the following morning at six o'clock, when our competitor was abeam. Then we slowly passed her. At eight she was on the quarter, and two hours later she was lost in the fog-bank astern.

But now all thoughts are shoreward bent. The sailors say we shall reach New York in the evening, and the burning question of the steerage is, " Shall we get ashore to-night ?"

Trunks are already being packed, friendships broken off, and much-creased clothing being put on. By two o'clock a nervous excitability holds us all; for the smell of the land is in our nostrils, the water has taken a greenish cast, and Sandy Hook is in sight.

From this on, an eager crowd hangs over the bulwarks, gazing with curious eyes at the beginnings of the new country.

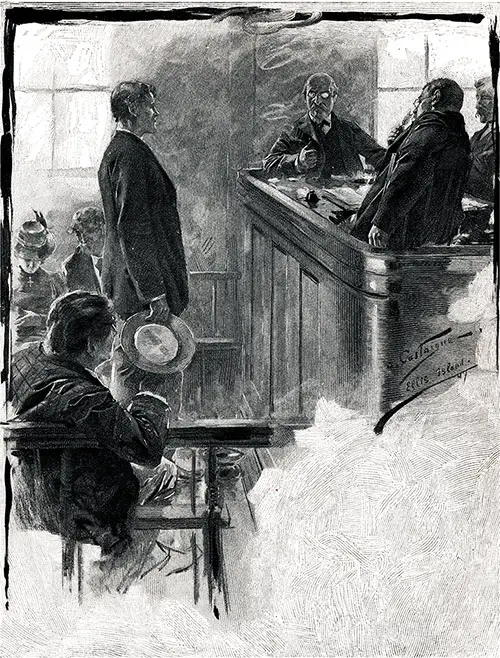

Some Immigrants End Up at the Board of Special Inquiry at Ellis Island. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145bc2be2b

Disembarking from the Steamer

An hour after sundown our steamer was made fast alongside her pier in the North River. The saloon and second-cabin passengers proceeded to stream down the gangway at once; but we, being immigrants, were roped well back, and carefully guarded. For the steamship company is responsible to the government for every immigrant it brings.

If any escape before being turned over to the proper authorities at Ellis Island, the company is liable to a heavy fine. Not being well up in the immigration laws; however, the whole four hundred of us crowded to the dock side of the vessel and waited impatiently to be loosed. After an hour or so it was announced that none but those who could show citizen's papers would be allowed to land.

At this a howl of disappointment went up from the land-hungry crowd. Threats, oaths, and wailings were heard on every side. It was an outrage, some said, to be brought alongside the wharf, and then imprisoned like thieves. If the cabin folks got ashore, why could not we? There were two niggers in the second cabin, and they got ashore. Were niggers better than white people?

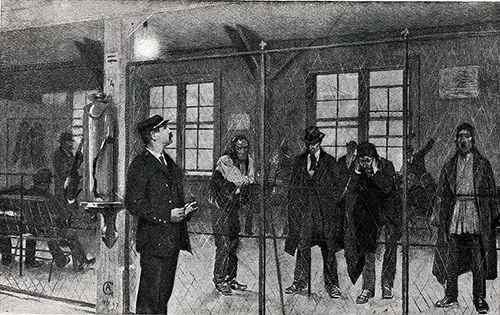

Immigrants Await Deportation in the Deported Pen at Ellis Island. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145bf6f693

"An' d' ye call this a free counthry?" cried a big Irishman, shaking his brawny fist under my unoffending nose. Fwhat wid inspections, an' examinations, an' vaccinations, an' bein' numbered, an' ticketed, an' stamped, an' the divil knows fwhat all--fwhat I'd loike to know is, where 's the freedom av ut ?

Taking the Barge to Ellis Island for Processing

We put in one more hot, uncomfortable night aboard, praying for morning; but when it came, a steamer leaving port blocked the way, and we could not leave the vessel until eleven o'clock.

For two hours after this, we were baked on the pier while the custom-house officers were overhauling our baggage. Then, each in his group, we were packed aboard a barge and towed down to Ellis Island.

In the steerage of any vessel, one can get only a partial knowledge of the class which immigrates to this country. At Ellis Island, however, one can see it all.

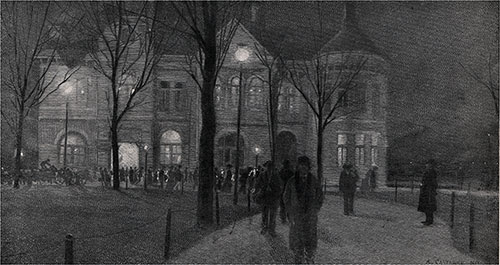

The same Saturday that we landed there, I was told that more than two thousand had passed through, eight hundred of them Italians. At Ellis Island, after being reinspected by the doctor, required to show what money we possessed and were closely questioned concerning our past, present, and future lives, we were finally discharged, and landed at the Battery about five o'clock.

It will thus be seen that the immigrant of today undergoes three examinations: first, at his home when he applies for passage; second, on board the vessel before departure; and third, upon his arrival in the country. The last is of necessity the strictest.

All cases considered by the inspectors as doubtful are detained and brought before the boards of special inquiry, who are empowered to hear and decide such matters. At Ellis Island, these boards sit every day of the year, and during the time to which I have referred heard no less than 40,539 cases.

Any immigrant found to be insane, a pauper, entering contrary to the alien contract labor laws, or for any cause incapable of earning a livelihood, is debarred, and returned to the country from which he came, at the expense of the steamship line that brought him.

It may be interesting to note here that, according to the report of the commissioner-general of immigration, 343,267 immigrants arrived between July 1, 1895, and June 30, 1896. Of these, 2,799 were returned, 776 being unlawfully under contract, and the remainder mainly paupers.

These figures show an increase of 84,731 over the previous fiscal year, a somewhat alarming fact when we note that 76,443 of this number hailed from Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Russia.

The question whether this stream of immigration, which is pouring into the country at the rate of about 830 per week all the year round, shall be encouraged or dammed, is a many-sided one, and not the concern of this paper.

But when one sees the mass of deep cosmopolitan humanity such as is to be found at Ellis Island, one cannot help feeling that to assimilate it the country needs an excellent digestion.

I saw the last of my steerage acquaintances at the Barge Office. Before leaving, I had the pleasure of being introduced to the " little whistler's brother, the boss from Brooklyn. From the old Irishman I was glad to hear that the shamrock was not only alive, but was " growin' foinely."

My young sailor friend I found bidding his four-days'-old love good-bye with as much blessing as though he had known her for the same number of years.

She, with her white veil turned up, showed a very red little nose and a very tremulous little mouth. I waited patiently for the end, and was at last rewarded by seeing her relatives draw her unwillingly away.

The Arrival of New Immigrants at the Battery Park Immigration Office. The Century Magazine, February 1898. GGA Image ID # 145c04b1d9

My friend then turned, and upon seeing me, hastened to inform me that he was going to marry the young lady. I congratulated him, and went my way up-town, believing in my cynical heart that his promise would end as most sea promises do.

Before two months were over, however, I received a card announcing the wedding; and since then I have called upon them in their snug little home near Boston.

He is now a shipper for a wholesale house in the city; and she—is still making dresses, for she was a dressmaker. The garments she makes now, however, will not go out of the family.

Epilog

Personally, I consider a trip in the steerage an excellent thing for a man. It knocks the conceit out of him.

When I entered upon my role as emigrant, I provided myself with a well-worn suit of clothes, an old hat, and a flannel shirt. I allowed my beard to grow, eschewed collars and cuffs, and made myself up for the part. At first, with a self-consciousness born of such ventures, I feared that my disguise would be seen through; but, alas for my pride!

I found in the steerage a valley of humiliation. The ship's company shoved me along the decks and swore at me without prejudice; the saloon and second-cabin passengers who occasionally stepped gingerly and curiously into our quarters looked me squarely in the eyes without a sign of recognition, and the steerage quietly opened its dirty arms and took me in without question.

Whitmarsh, H. Phelps, and A. Castaigne, Illustrator, "The Steerage of Today - A Personal Experience," in The Century Magazine, Volume LV, Number 4, February 1898, p. 528-543.