The Fellowship of the Steerage - 1905

A Narrative of the conditions of steerage accommodations aboard steamships circa 1905

"The steerage ought to be and could be abolished by law. It is true that the Italian and Polish peasant may not be accustomed to better things at home and might not be happier in better surroundings nor know how to use them; but it is a bad introduction to our life to treat him like an animal when he is coming to us. "

BACK of Warsaw, Vienna, Naples and Palermo, with no place on the world's map to mark their existence, are small market towns to which the peasants come from their hidden villages.

They come not as is their wont on feast and fast days, with song and music, but solemnly; the women bent beneath their burdens, carried on head or back, and the men who walk beside them, less conscious than usual of their superiority.

The women have lost the splendour which usually marks their attire. Their embroidered, stiffly starched petticoats, flowered aprons and gay kerchiefs have disappeared, and instead they have put on more sombre garb, some cast off clothing of our civilization. The men, too, have left their gayer coats behind them, to wear the shoddy ones which neither warm nor become them.

Beneath the black cross which marks the boundary of the Polish town, they usually rest themselves. The cross was erected when the peasants were liberated from serfdom, and beneath it every wanderer rests and prays : every wanderer but the Jew, for whom the cross symbolizes neither liberty nor rest.

These towns which used to be buried in a cloud of dust in the summer and a sea of mud in the winter time; to which the peasant came but rarely, and then only to do his petty trading or his quarrelling before the law, are the first catch basins of the little percolating streams of emigration, and have felt their influence in increased prosperity.

They are the supply stations where much of the money is spent on the way out, and into which the money flows from the mining camps and industrial centres in America.

One little house leans hospitably against the other, a two-story house marks the dwelling of nobility, and the power of the law is personified in the gendarmes, who, weaponed to the teeth, patrol the peaceful town.

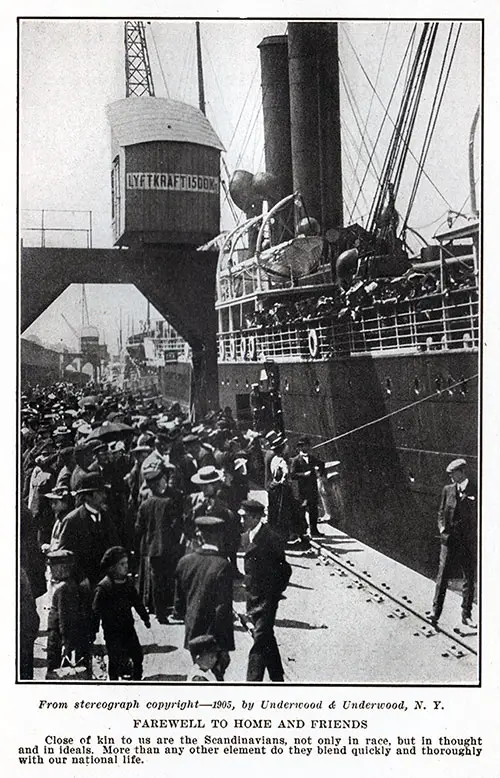

From Stereograph copyright-1905, by Underwood & Underwood, N. Y.

Farewell to Home and Friends

Close of kin to us are the Scandinavians, not only in race, but in thought and in ideals. More than any other element do they blend quickly and thoroughly with our national life.

In Russia, before one may emigrate, many painful and costly formalities must be observed, a passport obtained through the governor and speeded on its way by sundry tips.

It is in itself an expensive document without which no Russian subject may leave his community, much less his country. Many persons, therefore, forego the pleasure of securing official permission to leave the Czar's domain, and go, trusting to good luck or to a few rubles with which they may close the ever open eyes of the gendarmes of the Russian boundary.

Austrian and Italian authorities also require passports for their subjects. but they are less costly and are granted to all who have satisfied the demands of the law.

These formalities over, the travellers move on to the market square, a dusty place, where women squat, selling fruits and vegetables; the plaster cast and gaily decorated saints, stoically receiving the adoration of our pilgrims, who come for the last time with a petition which now is for a prosperous journey.

There also, the agent of the steamship company receives with just as much feeling their hard earned money in exchange for the long coveted " Ticket," which is to bear them to their land of hope.

From hundreds of such towns and squares, thousands of simple-minded people turn westward each day, disappearing in the clouds of dust which mark their progress to the railroad station and on towards the dreaded sea.

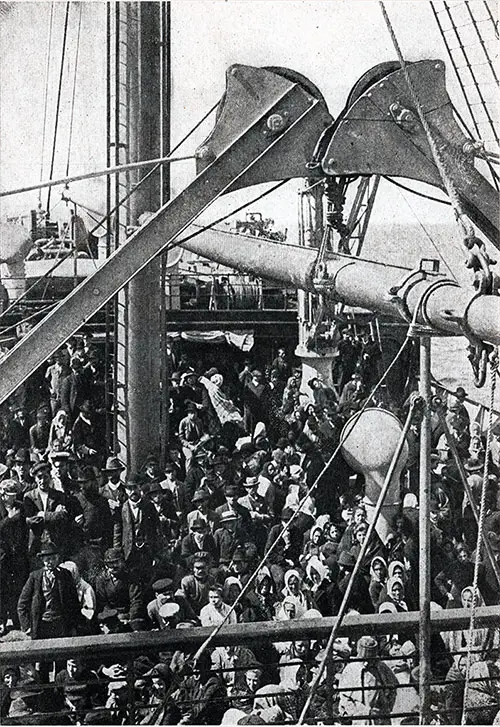

Steerage Passengers Gathering Before The Voyage

From the small windows of fourth-class railway carriages they get glimpses of a new world, larger than they ever dreamed it to be, and much more beautiful.

Through orderly and stately Germany, with its picturesque villages, its castled hills and magnificent cities they pass; across mountains and hills, and by rushing rivers, until one day upon the horizon they see a forest of masts wedged in between the warehouses and factories of a great city.

Guided by an official of the steamship cornpany whose wards they have become, they alight from the train; but not without having here and there to pay tribute to that organized brigandage, by which every port of embarkation is infested.

The beer they drink and the food they buy, the necessary and unnecessary things which they are urged to purchase, are excessively dear, by virtue of the fact that a double profit is made for the benefit of the officials or the company which they represent.

The first lodging places before they are taken to the harbours, are dear, poor and often unsafe. Much bad business is done there which might be controlled or entirely discontinued.

For instance in Rotterdam three years ago, coming with a party of emigrants, we were met by an employee of the steamship company and taken in charge, ostensibly to be guided to the company's offices near the harbour.

On the way we were made to stop at a dirty, third-class hotel (whose chief equipment was a huge bar) and were told to make ourselves comfortable.

While we were not compelled to spend our money, we were invited to do so, urged to drink, and left there fully three hours until this same employee called for us.

I complained to the company through the only official whom I could reach, and who no doubt was one of the beneficiaries, for the complaint did not travel far.

This is only the remnant of an abuse from which the emigrant and the country which received him, used to suffer; for our stringent immigration laws have made it more profitable to treat the immigrant with consideration and to look after his physical welfare.

Yet, admirable as is the machinery which has been set up at Hamburg for the reception of the emigrant, these minor abuses have not all passed away and while care is taken that his health does not suffer and that his purse is not completely emptied, he is still regarded as prey.

The Italian government safeguards its emigrants admirably at Naples and Genoa; but other governments are seemingly unconcerned. When the official has done with the emigrants, they are taken to the emigrant depot of the company (which in many cases is inadequate for the large number of passengers), their papers are examined and they are separated according to sex and religion.

At Hamburg they are required to take baths and their clothing is disinfected; after which they constantly emit the delicious odours of hot steam and carbolic acid.

The sleeping arrangements at Hamburg are excellent. Usually twenty persons are in one ward, but private rooms which have beds for four people can be rented.

The food is abundant and good, plenty of bread and meat are to be had, and luxuries can be bought at reasonable prices. At Hamburg music is provided and the emigrants may make merry at a dance until dawn of the day of sailing.

The medical examination is now very strict, yet seemingly not strict enough; for quite a large percentage of those who pass the German physicians are deported on account of physical unfitness.

I wish to make this point here, and emphasize it: that restrictive immigration has had a remarkable influence upon the German and Netherlands steamship companies, in that they have become fairly humane and decent, which they were not; but improvement in this direction is still possible.

Day of Embarkation - Steerage Accommodations

The day of embarkation finds an excited crowd with heavy packs and heavier hearts, climbing the gangplank. An uncivil crew directs the bewildered travellers to their quarters, which in the older ships are far too inadequate, and in the newer ships are, if anything, worse.

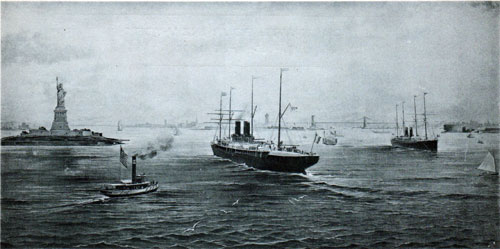

Colorized Postcard of the Kaiser Wilhelm II Entering the Harbor of New York June 1905. GGA Image ID # 14796fae3a

Clean they are; but there is neither breathing space below nor deck room above, and the 900 steerage passengers crowded into the hold of so elegant and roomy a steamer as the Kaiser Wilhelm II, of the North German Lloyd line, are positively packed like cattle, making a walk on deck when the weather is good, absolutely impossible, while to breathe clean air below in rough weather, when the hatches are down is an equal impossibility.

The stenches become unbearable, and many of the emigrants have to be driven down; for they prefer the bitterness and danger of the storm to the pestilential air below.

The division between the sexes is not carefully looked after, and the young women who are quartered among the married passengers have neither the privacy to which they are entitled nor are they much more protected than if they were living promiscuously.

The food, which is miserable, is dealt out of huge kettles into the dinner pails provided by the steamship company. When it is distributed, the stronger push and crowd, so that meals are anything but orderly procedures.

On the whole, the steerage of the modern ship ought to be condemned as unfit for the transportation of human beings; and I do not hesitate to say that the German companies, and they provide best for their cabin passengers, are unjust if not dishonest towards the steerage .

Take for example, the second cabin which costs about twice as much as the steerage and sometimes not twice so much; yet the second cabin passenger on the Kaiser Wilhelm II has six times as much deck room, much better located and well protected against inclement weather.

Two to four sleep in one cabin, which is well and comfortably furnished; while in the steerage from 200 to 400 sleep in one compartment on bunks, one above the other, with little light and no comforts.

In the second cabin the food is excellent, is partaken of in a luxuriantly appointed dining-room, is well cooked and well served; while in the steerage, the unsavoury rations are not served, but doled out, with less courtesy than one would find in a charity soup kitchen.

The steerage ought to be and could be abolished by law. It is true that the Italian and Polish peasant may not be accustomed to better things at home and might not be happier in better surroundings nor know how to use them; but it is a bad introduction to our life to treat him like an animal when he is coming to us.

He ought to be made to feel immediately, that the standard of living in America is higher than it is abroad, and that life on the higher plane begins on board of ship.

Every cabin passenger who has seen and smelt the steerage from afar, knows that it is often indecent and inhuman; and I, who have lived in it, know that it is both of these and cruel besides.

On the steamer Noordam, sailing from Rotterdam three years ago, a Russian boy in the last stages of consumption was brought upon the sunny deck out of the pestilential air of the steerage.

I admit that to the first cabin passengers it must have been a repulsive sight -- this emaciated, dirty, dying child; but to order a sailor to drive him down-stairs, was a cruel act, which I resented.

Not until after repeated complaints was the child taken to the hospital and properly nursed, On many ships, even drinking water is grudgingly given, and on the steamer Staatendam, four years ago, we had literally to steal water for the from the second cabin, and that of course at night.

On many journeys, particularly on the Fürst Bismark, of the Hamburg American line, five years ago, the bread was absolutely uneatable, and was thrown into the water by the irate emigrants.

In providing better accommodations, the English steamship companies have always led; and while the discipline on board of ship is always stricter than on other lines, the care bestowed upon the emigrants is correspondingly greater.

At last the passengers are stowed away, and into the excitement of the hour of departure there comes a silent heaviness, as if the surgeon's knife were about to cut the arteries of some vital organ.

Homesickness, a disease scarcely known among the mobile Anglo-Saxons, is a real presence in the steerage; for there are the men and women who have been torn from the soil in which through many generations their lives were rooted.

Steerage Passengers from Many Countries

No one knows the sacred agony of that moment which fills and thrills these simple minded folk who, for the first time in their lives face the unknown perils of the sea.

The greater the distance which divides the ship from the fast fading dock, the nearer comes the little village, with its dusty square, its plaster cast saints and its little mud huts.

From far away Russia a small pinched face looks out and a sweet voice calls to the departing father, not to forget Leah and her six children, who will wait for tidings from him, be they good or ill.

From Poland in gutteral speech comes a : "God be with you, Bratye (brother)," strong oak of our village forest and our dependence; the Virgin protect thee."

The Slovak feels his Maryanka pressing her lips against his while she sobs out her lamentation, and he, to keep up his courage, gives a "strong pull and a long pull" at the bottle, out of which his white native palenka gives him its last alcoholic greeting.

Silent are the usually vociferous Italians, whose glorious Mediterranean is blotted out by the sombre gray of the Atlantic; they shall not soon again see the full orbed moon shining upon the bay of Naples, sending from heaven to earth a path of silver upon which the blessed saints go up and down.

In the silence of the moment there come to them the rattle of carts and the clatter of hoofs, the soft voice of a serenade and then the sweet scented silence of an Italian night.

They all think, even if they have never thought much before; for the moment is as solemn as when the padre came with his censer and holy water, or when the acolytes rang the bells, mechanically, on the way to some death-bed.

It is all solemn, in spite of the band which strikes the well-known notes of "Lieb Vaterland, magst ruhig sein," and makes merrier music each moment to check the tears and to heal the newly made wounds.

They try to be brave now, struggling against homesickness and fear, until their faces pale, and one by one they are driven down into the hold to suffer the pangs of the damned in the throes of a complication of agonies for which as yet, no pills or powders have brought soothing.

But when the sun shines upon the Atlantic, and dries the deck space allotted to the steerage passengers, they will come out of the hold one by one, wrapped in the company's gray blankets; pitiable looking objects, ill-kempt and ill-kept.

Stretched upon the deck nearest the steam pipes, they await the return of the life which seemed "clean gone" out of them. -- It is at this time that cabin passengers from their spacious deck will look down upon them in pity and dismay, getting some sport from throwing sweetmeats and pennies among the hopeless looking mass, out of which we shall have to coin our future citizens, from among whom will arise fathers and mothers of future generations.

Steerage Passengers On Deck of Ocean Liner as Seen by a Lady of the First Cabin. The Fellowship of the Steerage Makes Good Comrades, Where no Barriers Exist and Introductions are Neither Possible nor Necessary. From Stergraph. Copyright © 1905 by Underwood & Underwood, NY. GGA Image ID # 146b639daa

The fellowship of the Steerage makes good comrades, where no barriers exist and introductions are neither possible nor necessary.

This practice of looking down into the steerage holds all the pleasures of a slumming expedition with none of its hazards of contamination; for the barriers which keep the classes apart on a modern ocean liner are as rigid as in the most stratified society, and nowhere else are they more artificial or more obtrusive.

A matter of twenty dollars lifts a man into a cabin passenger or condemns him to the steerage; gives him the chance to be clean, to breathe pure air, to sleep on spotless linen and to be served courteously; or to be pushed into a dark hold where soap and water are luxuries, where bread is heavy and soggy, meat without savour and service without courtesy.

The matter of twenty dollars makes one man a menace to be examined every day, driven up and down slippery stairs and exposed to the winds and waves; but makes of the other man a pet, to be coddled, fed on delicacies, guarded against draughts, lifted from deck to deck and nursed with gentle care.

The average steerage passenger is not envious. His position is part of his lot in life; the ship is just like Russia, Austria, Poland or Italy. The cabin passengers are the lords and ladies, the sailors and officers are the police and the army, while the captain is the king or czar.

So they are merry when the sun shines and the porpoises roll, when far away a sail shines white in the sunlight or the trailing smoke of a steamer tells of other wanderers over the deep.

"Here, Slovaks, bestir yourselves; let's sing the song of the Little red pocket-book' or The gardener's wife who cried.' Too sad ?' you say ? Then let's sing about the Red beer and the white cakes.'" So they sing :

"Brothers, brothers, who'll drink the beer,

Brothers, brothers, when we are not here ?

Our children they will drink it then

When we are no more living men.

Beer, beer, in glass or can,

Always, always finds its man."

Other Slays from Southern mountains, sing their stirring war song :

Out there, out there beyond the mountains,

Where tramps the foaming steed of war,

Old Jugo calls his sons afar;

To aid ! To aid ! in my old age

Defend me from the foeman's rage." Out there, out there beyond the mountains

My children follow one and all,

Where Nikita your Prince doth call;

and steep anew in Turkish gore

The sword Czar Dushan flashed of yore,

Out there, out there beyond the mountains."

If the merriment rises to the proper pitch, there will be dancing to the jerky notes of an harmonica or accordion; for no emigrant ship ever sailed without one of them on board.

The Germans will have a waltz upon a limited scale, while the Poles dance a mazurka, and the Magyar attempts a wild czardas which invariably lands him against the railing; for it needs steady feet as well as a steadier floor than the back of this heaving, rolling monster.

Men and women from other corners of the Slav world will be reminded of the spinning room or of some village tavern; and joining hands will sing with appropriate motions this, not disagreeable song, to Katyushka or Susanka, or whatever may be the name of this " Honey-mouth."

We are dancing, we are dancing,

Dancing twenty-two;

Mary dances in this Kolo,

Mary sweet and true;

What a honey mouth has Mary,

Oh ! what joyful bliss !

Rather than all twenty-two

I would Mary kiss."

Greeks, Servians, Bulgarians, Magyars, Italians and Slovaks laugh at one another's antics and while listening to the strange sounds, are beginning to enter into a larger fellowship than they ever enjoyed; for so close as this many of them never came without the hand upon the hilt or the finger upon the trigger.

When Providence is generous and grants a quiet evening, the merriment will grow louder and louder, drowning the murmur of the sea and silencing the sorrows of the yesterday and the fears for the morrow.

"Yes, brothers, we are travelling on to America, the land of hope; let us be merry. Where are you going, Czeska Holka?" (a pet name for a Bohemian girl). "

To Chicago, to service, and soon, I hope, to matrimony; that's what they say, that you can get married in America without a dowry and without much trouble." Ah, yes; and get unmarried again without much trouble; but of this fact she is blissfully ignorant." "Where are you going, signor?"

"Ah, I am going to Mulberry Street; great city, yes, Mulberry Street, great city." "Polak, where are you going?" "Kellisland." "Where do you say?" "Kellisland, where stones are and big sea." "Yes, yes, I know now : Kelly's Island in Ohio. Fine place for you, Polak; powder blast and white limestone dust, yet a fine sea and a fine life."

All of them are going somewhere to some one; not quite strangers they; some one has crossed the sea before them. They are drawn by thousands of magnets and they will draw others after them.

We have all become good comrades; for fellowship is easily begotten by the fellows in the same ship, especially in the steerage, where no barriers exist and where no introductions are possible or necessary.

I am sharing many confidences; of young women who go to meet their lovers; of young men who go to make their fortunes; of bankrupts who have fled the heavy arm of the law; of women hiding moral taint; of countless ones who are hiding grave physical infirmities; and of some who have lost faith in God and men, in law and justice.

Yet most of them believe with a simpler faith than our own; God is real to them and His providence stretches over the seas. No morning, no matter how tumultuous the waves, but the Russian Jews will put on their phylacteries, and kissing the sacred fringes which they wear upon their breasts, will turn towards the East and the rising Sun, to where their holy temple stood.

Rarely will a Slav or Italian go to bed without committing himself to the special care of some patron saint.

Vice there is, crude, rough vice, down here in the steerage. Yes, they drink vodka, -- even that rarely; but up in the cabin they drink champagne and Kentucky whiskies, the same devils with other names.

Seldom do the steerage passengers gamble -- a friendly game of cards perhaps, here and there; while up in the cabin, from sunlight until dawn, poker chips are piled and pass to and fro among daintily attired men and women.

There are rough jests in this steerage, and scant courtesy; but virtue is as precious here as there, although kept under tremendous temptation. I have crossed the ocean hither and thither, often in the steerage, more often in the cabin; and I have found gentlemen in dirty homespun in the one place, and in the other supposed gentlemen who were but beasts, although they had lackeys to attend them, and suites of rooms in which to make luxurious a useless existence.

The steerage brings virtue and vice in the rough. A dollar might not be safe, and yet as safe as a whole bank up in the cabin; the steerage might steal a loaf of white bread or a tempting cake, but it has not yet learned how to corner the wheat market; the men in the steerage might be tempted to steal a ride upon a railroad, but in the cabin I have met rascals who had stolen whole railroads, yet were called " Captains of Industry."

Down in the steerage there is a faith in the future, and in the despair which often overwhelms them, I needed but to whisper : " Be patient, this seems like Hell, but it will soon seem to you like Heaven."

Yes, this Heaven is coming; coming down almost from above, on yonder fringe of the sea, for far away trails the low lying smoke of the pilot boat, and but a little farther off is -- landland.

None but the shipwrecked and the emigrants, these way-farers who come to save and be saved, know the joy of that note which goes from lip to lip as it echoes and reechoes in thirty languages, yet with the one word of throbbing joy, -- land -- land -- America.

Steerage Passengers First View of the New World

Steerage Passengers Eagerly Turned Their Eyes to the Statue of Liberty. Leslie's Monthly Magazine, May 1904. GGA Image ID # 14631c3ee9

The gay spirits soon flag when land is heralded; for Ellis Island is ahead, with its uncertainties, and the men and women who were the merriest and who most often went to the bar, thus trying to forget, now are sober, and reflect.

The troubled ones are usually marked by their restless walk and by their eagerness to seek the confidences of those who have tested the temper of the law in this unknown Eldorado.

Not long ago, on one of the ships in which I sailed, there was in the steerage, a monk, who neither walked nor talked like one. He shunned me, not because of my heresies, but because of my Latin, and although he mumbled out of a prayer-book and unskillfully counted his beads, I knew that " The devil a monk was he."

On the eve of the great day of landing, he was pacing the deck, evidently in an unreverential mood, and I too was there, being one of those who prefer the biting wind of the night to the polluted air of the steerage.

He came close to me as we walked, and hesitatingly asked me in a French to which clung a peculiar dialect never spoken in monasteries, whether I had been in America before.

When I replied in the affirmative, he inquired all about the examination of baggage and of men, and when I told him how strict it is, that nothing is hid from the lynx eyes of the custom-house officials, and that nothing is sacred to them, not even the body of a monk, he grew visibly excited.

Stealthily he drew from under the folds of his cassock, a stone, a large, brilliant, tempting diamond, and said : "You may have that." As I took it between my fingers, I detected traces of the torn rim of its setting, and passed it back into the trembling hand of his "Reverence."

"You needn't be afraid of that," he said; "I am one of the monks driven out of France, and I am taking the treasures of the Brotherhood over. I am afraid of the high duty and it will be cheaper for me to give you that diamond which is a pendant from the jewels of the Virgin, than to pay for what I have; that is, if you will help me to pass this little bag safely in."

With this he drew aside his cassock and fumbling in the folds brought to light a little bag which he would have handed to me, but I assured him that I was not a smuggler even for pious purposes, and after darting at me an impious glance, he disappeared into the steerage.

The next day at Quarantine, a messenger boy of unusual size came on board and calling out the names of a rather large number of steerage passengers handed them telegrams which were written in English and were rather suspiciously vague. -- "Pavel Moticzka, -- Ivan Kovaloff, -- Isaac Goldberg," and last, -- "Jaques Rosenstein."

My friend the monk nearly jumped out of his cassock to reach for his message, and the "Boy," who made most remarkable haste for a telegraph messenger, slipped a pair of handcuffs where only rosaries hung; and a Jewish jeweller's clerk from Paris, who was running away with the best part of his employer's diamonds, -- was in the toils of the law.

Some years ago when the steerage of the Hamburg American Line had not been made even partially decent by our stringent immigration laws, over 500 passengers, booked for the Fürst Bismark, at that time the swiftest boat of the line, were, without explanation or notification, stowed away in a freight boat scheduled to cross in twelve days, but never having actually made the trip in less than sixteen days.

The quarters were very close but the number of passengers was not excessively large, the weather was favourable, and blissfully ignorant of the slowness of the ship, we were comparatively happy.

We were divided about equally into Russian Jews, Slays and Italians, and there was very little choice so far as comradeship was concerned. The passengers were all fairly dirty, the Italians being easily in the lead, with the Russian Jews a good second, and the Slays as clean as circumstances allowed.

The Italians were from the South of Italy and had lost the romance of their native land but not the fragrance of the garlic. They quarrelled somewhat loudly and gesticulated wildly; but were good neighbours during those sixteen days.

They were shy and not easily lured into confidences by one who knew their language but poorly, in spite of the fact that he knew their country well and followed it.

In sixteen days the average American has a chance to discover at least one thing which he has found it hard to believe; that all Italians are not alike, that they do not look alike, and that they are not all Anarchists.

When some relationship was established between us, and I had to serve as the link among the three races, we had a grand "Festa" to which the Slays contributed some gutteral songs and clumsy dances, and the Italians, sleight of hand performances which made them appear still more uncanny to the Slays.

They also supplied a Marionette theatre, of the Punch and Judy show variety, and "last but not least," music from a hurdy-gurdy which played the dulcet notes of "Cavalliero Rusticana" and a dashing tune about "Marghareta, Marghareta."

"Signors and Signorinas," said Pietro, after he had played all the tunes of his limited repertoire, "I have the great honour of presenting to you the national anthem of the great American country to which we are travelling." He turned the crank, and out came, -- the ragtime notes of "Ta -- ra -- ra -- boom -- de -- a."

The last number on the program was a song by a Russian Jewess, a woman whose beauty was marred by bleached hair which had grown rusty, and by a complexion upon which rouge and powder had done their worst.

Her voice which was strong rather than melodious, had in it an element of artificiality evidently begotten on the stage. She at once became the star among our entertainers, and though her culture was superficial, she was by far the best company for me.

Her parents, she told me, had been well to do Jews in a market town in Russia. They had broken away from many of the observances and traditions of their religion, they and their children followed all the latest fashions, a governess imported from France brought with her Paul de Kock's novels and other elevating (?) Parisian literature; music teachers came, who discovered in the only daughter a voice which of course, had to be cultivated in Vienna.

There were concerts which the father's money arranged, a few glowing press notices at so much a line, and finally the fruitless struggle to appear in opera.

Then came one of those Anti-Semitic riots, those brutal outpourings of human hate which she was unable to describe. All she could say over and over again was, "Strashno, Strashno," "it was terrible, terrible."

The house in which she had lived was a wreck, her father beaten to death, and she -- she could not say it; but I knew. She told of women whose mutilated bodies were torn open, and of children whose heads were beaten together until they were a bleeding mass. Yes, indeed, it was " Strashno, Strashno," terrible, terrible.

Somewhat early in her girlhood, a clerk in her father's store "had looked upon her, and loved her" with a youth's ardour; but she had scorned him, as well she might scorn this uncultured, stupid looking son of Abraham.

Again and again he asked her to be his wife, until through her entreaty, her father drove him out of the store. She told me much of her life and perhaps many things which she told me were not true.

I knew for instance, that she had not sung before the Czar of Russia, that Hanslick the great musical critic of Vienna did not predict for her a Patti's fame and fortune; nor did I believe that a young millionaire in Berlin blew out his brains because she would not marry him.

But I did believe that the poor clerk went to New York, that he had worked day and night in a sweat shop pressing cloaks, that out of his earnings he had supported her in the vain struggle to attain Grand Opera, and that now she was on her way to reward his faithfulness and become his wife.

"What is it like, this America?" "What kind of life awaits one on the East-side?" "What social status has a cloak presser in New York?" "What chance is there for one to reach the goal of Grand Opera?"

These and other questions she hurled at me while the line upon the horizon grew clearer, and the hearts of men and women heavy from expectation.

On this ship too, Susanka, a Slovak girl nursed her way across the Atlantic, giving food to a little Magyar baby which she despised; and while she rocked the restless little one to sleep and sang her Slavic lullaby, "Hi-u, Hi-u, Hi-u-shkee-e" -- one could see in her heavy face her heart's hunger for her own child.

Oh ! Pany velkomosny (mighty sir), my little child ! I had to leave it with a stara baba (old woman) and it was gray, ashen gray when I left it, and it will die, it will die ! "and she grew frantic in her grief as she rocked the Magyar child to and fro, Hi-u, Hi-u, Hi-u-shke-e-e-e."

"Who was to blame, Susanka?" The look of pain changed to one of fiery anger as she sent back across the sea, a curse, long and terrible, against her betrayer.

Yes, those are heavy hours and long, on that day when the ship is circled by the welcoming gulls, and the fire-ship is passed, while the chains rattle and the baggage is piled on the deck.

"Will they let me in, signor?" "Why should they not, Antonio?" "Ah I signor, I have not always been a free man. They held me in jail for four years. Will they know it in America? I stabbed a man, -- yes, signor."

"Will they let us in, Guter Herrleben?" anxiously asks Yankev: his wife Gietel and six children are with him and one of the boys lies motionless upon the hatch, pale, worn and almost gone. "Consumption? yes; he was so well, but we were smuggled over and driven by the gendarmes, and had to be out in the damp, and he caught cold and a cough came and you can see, Guter Herrleben, quick consumption!"

Yankev, and Gietel his wife, had an appalling story to tell, and I listened to it as we squatted on deck under the twinkling stars. The moon shone in silvery splendour upon the quiet water, and I wondered why the sea did not grow angry, the constellations pale, and why the moon did not become red like blood at the horror of it all -- a horror which never can be told.

Imagine an Easter night, a night when Yankev and Gietel celebrated the liberation of Israel from Egyptian bondage. On the same night their Russian neighbours were celebrating the liberation of the human race from the power of death. The synagogue service was over.

They had told the story of Israel's passing through the Red Sea, and of the perishing of Pharoah's horsemen; Yankev had come home to the feast of unleavened bread and bitter herb; the neighbours had been to the church where until midnight, in darkness and silence, they mourned at the tomb of the slain Christ.

Then with the passing of the long and silent night they went from street to street shouting: " Christ is risen, Christ is risen, Christ is risen, indeed." But the mob came upon the defenseless home plundering and burning all in its fury, although mercifully sparing the lives of the now homeless and penniless family.

Others fared worse, for they had no money with which to bribe, while their daughters were older and good to look upon. It was a little place and just a little pogrom. It was not written about nor protested against; but what would have been the use ?

Dumb from agony we sat there and I had to breathe back into them the faith which they had almost lost, and the courage which had almost left them; a faith and courage which I myself did not possess.

In the peace of the night I could hear only the terror of the voice of the Lord saying : "Vengeance is Mine." The gentle Nazarene who came in love to conquer by love, I could scarcely see, and I yearned to make the Psalmist's prayer my own. "Blessed be the Lord Godwhich teacheth my hands to war and my fingers to fight."

That night and many another last night on board of ship, I listened to the stories of men and women who were fleeing from the terror of Russia's law.

Russians who had wrought in secret, who had planned great things and who had risked everything -- Bogdanoff, Philipoff, Lermontoff, Lehrman, Loewenstern.

Jews and Gentiles who had struck out in their blind fury, who had felt the terror of the law and the greater terror of taking, or trying to take, human life. Some guilty, some innocent; all of them caught in the same net.

Characteristic is the story of a Warsaw merchant who sailed with me on my last journey. On the evening of the 21st of April, 1906, he went to a dentist to have some work done. He went in the evening because he was busy in the daytime, and when he arrived the police were searching the house; after which all the inmates, dentist and patients, were taken to the police station and cast into prison.

Two hundred and fifty persons were together in a room large enough for twenty. The odours were frightful, as in common with all Russian prisons there were no toilet conveniences outside of that room, in which for three days they were left. After bribing the officials, twenty fortunate men, my informant among them, were given another room.

Nine weeks he remained there utterly unconscious of the reason for his detention; and only after the hard and faithful struggle of his wife was he released, -- without an apology, to find his business ruined and only sufficient money left to go to America.

On the same ship I met the widow of a Jewish physician, who was shot down in the act of binding the wounds of those fallen in the uprising of Moscow. Binding the wounds of soldiers and revolutionists alike, he was shot in the back by a police lieutenant who afterwards was promoted to a captaincy.

No, it is not easy to travel in the steerage; not because there is not room enough, nor air enough, nor food enough, although that is all true; but because it is hard to believe down there that the God of Israel is not dead, nor His arm shortened, if not broken, like those of the Greek deities.

Yet they still have faith in Him, these children of His, who have waited for the fulfillment of His promises. They still wait, although " Jerusalem the golden" is a far away dream, and they are scattered wanderers over the face of the earth.

Friday night, with the coming of the first star, all those who believed, met, to voice their faith in Jehovah.

In a corner of the steerage quarters, while the eyes of the Gentiles looked inquisitively on, they turned towards Zion, and lifting up their voices, greeted the Sabbath : "Come, my beloved, thou Sabbath bride," "Lcho dody L Crass Calo."

They sang this one joyous song of Israel, and stretched out their arms as if to press this spiritual bride to their rest-hungry souls.

They do not doubt that Jehovah will guide the destinies of Israel, and that the Sabbath bride will some day descend upon the earth to abide forever, bringing rest and peace to the Israel of God.

At last the great heart of the ship has ceased its mighty throbbing, and but a gentle tremor tells that its life has not all been spent in the battle with wind and waves.

The waters are of a quieter colour, and over them hovers the morning mist. The silence of the early dawn is broken only by the sound of deep-chested ferry-boats which pass into the mist and out of it, like giant monsters, stalking on their cross beams over the deep.

Day of Arrival

The steerage is awake after its restless night and mutely awaits the disclosures of its own and the new world's secrets. The sound of a booming gun is carried across the hidden space, and faint touches of flame struggling through the gray, are the sun's answer to the salute from Governor's Island.

The morning breeze, like a "Dancing Psaltress," moves gently over the glassy surface of the water, lifts the fog higher and higher, tearing it into a thousand fleecy shreds, and the far things have come near and the hidden things have been revealed.

The sky line straight ahead, assaulted by a thousand towering shafts, looking like a challenge to the strong, and a warning to the weak, makes all of us tremble from an unknown fear.

Steamship traffic near the Statue of Liberty, New York circa 1891. Photo by Berthaud.

The steerage is still mute; it looks to the left at the populous shore, to the right at the green stretches of Long Island, and again straight ahead at the mighty city.

Slowly the ship glides into the harbour, and when it passes under the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, the silence is broken, and a thousand hands are outstretched in greeting to this new divinity into whose keeping they now entrust themselves.

Some day a great poet will arise among us, who, catching the inspiration of that moment will be able to put into words these surging emotions; who will be great enough to feel beating against his own soul and give utterance to, the thousand varying notes which are felt and never sounded.

On this very ship are women who have left the burdens which crippled them, and now hope to walk erect; who have fled from the rough, polluting hands of persecuting mobs, that they may be able to guard their virtue and have it guarded by gallant men.

Here are hundreds of Slays who never knew aught but the yoke of czar or other potentate, whose minds have been enthralled by a galling autocracy, and whose closed eyes have never been permitted to see their own downtrodden strength. Now they shall have the opportunity to prove themselves and show the nobility of a peasant race.

Here are Italians from shores where classic art is stored, and the air is soft and full of melody; yet they were left uncouth, rough and unhewn. They come to a rougher but freer air, that they may grow into a gentler, stronger, nobler manhood and womanhood.

Melancholy Jews whose feet never knew a safe abiding place, are here, and their hope is that they may find the peace which went out from their race, when Jerusalem was laid waste and they were scattered among the nations of the earth.

He who thinks that these people scent but the dollars which lie in our treasury, is mightily mistaken, and he who says that they come without ideals has no knowledge of the children of men.

I found myself close to hundreds of these people, closest to the Russian Jews who most excited my sympathies; and one day when they heard that I had been in Bialistok, Kishinef and Odessa, that I knew the horror of it all and that I sympathized with them, they crowded around me almost like wild animals. What did they ask for above everything? Money?

No. The one loud cry was for a speech about America. "Preach to us," they said, "preach to us about America." It was a polyglot sermon which I preached that Sunday from the covered hatch which was my pulpit, and when I spoke to them of their new home and their new duties, they cheered me to the echo.

I have passed through this gateway more than ten times; I have sounded as far as a man can sound, the souls of men and women, and I have found them tingling from emotions, akin only to those which we more prosperous voyagers shall feel, when we have crossed the last sea and find ourselves in the presence of the great Judge.

Many of these emigrants expect to find more liberty, more justice, and more equitable law than we ourselves enjoy; they imagine that our common life is permeated by a noble idealism; and while they cannot give expression to their high anticipations they feel more loftily than we think them capable of feeling.

Many a time I have heard conversations between those who had read about America and those who were ignorant of its life, and invariably I have had to keep silence; for had I spoken I must have destroyed blessed illusions.

From the very people whom we call Sabbath breakers, I have heard glowing descriptions of an ideal American Sabbath, and from men to whom alcoholic beverages seemed essential to life, I have heard a defense of laws regulating the sale of liquor. If, in our superficial touch with them in our own country, we find them materialistic and dulled to what we call our higher life, they are not the only ones at fault.

Cabin and steerage passengers alike, soon find the poetry of the moment disturbed; for the quarantine and custom-house officials are on board, driving away the tourist's memories of the splendour of European capitals by their inquisitiveness as to his purchases.

They make him solemnly swear that he is not a smuggler, and upon landing, immediately proceed to prove that he is one.

The steerage passengers have before them more rigid examinations which may have vast consequences; so in spite of the joyous notes of the band, and the glad greetings shouted to and fro, they sink again into awe-struck and confused silence.

When the last cabin passenger has disappeared from the dock, the immigrants with their baggage are loaded into barges and taken to Ellis Island for their final examination.

Steerage Passengers At The Gateway

THE barges on which the immigrants are towed towards the island are of a somewhat antiquated pattern and if I remember rightly have done service in the Castle Garden days, and before that some of them at least had done full service for excursion parties up and down Long Island Sound.

The structure towards which we sail and which gradually rises from the surrounding sea is rather imposing, and impresses one by its utilitarian dignity and by its plainly expressed official character.

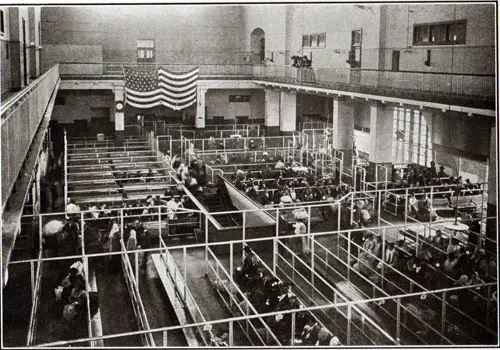

Immigrants arrive via Ferry at Ellis Island circa 1910. Photograph by Underwood & Underwood.

With tickets fastened to our caps and to the dresses of the women, and with our own bills of lading in our trembling hands, we pass between rows of uniformed attendants, and under the huge portal of the vast hall where the final judgment awaits us.

We are cheered somewhat by the fact that assistance is promised to most of us by the agents of various National Immigrant Societies who seem both watchful and efficient.

Mechanically and with quick movements we are examined for general physical defects and for the dreaded trachoma, an eye disease, the prevalence of which is greater in the imagination of some statisticians than it is on board immigrant vessels.

THE SHEEP AND THE GOATS. In the great examination hall, they wait, some with curiosity, some with anxiety, the decision that shall give them entrance to the new home or consign them again to the Old World strife.

From here we pass into passageways made by iron railings, in which only lately, through the intervention of a humane official, benches have been placed, upon which, closely crowded, we await our passing before the inspectors.

Already a sifting process has taken place; and children who clung to their mother's skirts have disappeared, families have been divided, and those remaining intact, cling to each other in a really tragic fear that they may share the fate of those previously examined.

A Polish woman by my side has suddenly become aware that she has one child less clinging to her skirts, and she implores me with agonizing cries, to bring it back to her.

In a strange world, at the very entrance to what is to be her home, without the protection of her husband, without any knowledge of the English language, and with no one taking the trouble to explain to her the reason, the child was snatched from her side. Somewhere it is bitterly crying for its mother, and each is unconscious of the other's fate.

" Gdeye moya shena" (where is my wife?) an old Slovak cries as he looks wildly about for her, whose physique was suspected of being belowthe normal and who was passed on for further examination.

A Russian youth, stalwart and strong, is separated from his household which came together to settle in Dakota; but now he, the mainstay of the family, is gone and they are perplexed and distracted.

A little girl scarcely five years of age, cries : "Mitter, mitter, ich will zu meiner mitter gehen"; she is there alone and uncomforted, surrounded by rough-looking men, while not far away her mother is working herself into hysterics because she must await in the detention room the supreme decision.

A woman with three children has two of them taken from her because they are suspected of disease and found to be afflicted by trachoma; the mother also has the disease, but her husband, now an American citizen, comes to claim her, and she passes in while the little ones are held in custody by the immigration authorities.

One by one we pass the inspectors; we show our money and answer the questions which are numerous and pertinent.

The average immigrant obeys mechanically; his attitude towards the inspector being one of great respect. While the truth is not always told, many of the lies prepared prove both inefficient and unnecessary.

WILL THEY LET ME IN? It is a serious matter to many a man who has invested his all in a ticket tor the New World to face the possibility of rejection.

On one of the boats very recently a number of young women were imported for immoral purposes, and each of them was supposed to be married to the attendant agent of a firm which conducts an international business.

The young man having announced himself as married to the woman accompanying him, was asked, "Where were you married?" "In Paris." "Who married you?" "Pere Abelard." "When were you married? " "The fifteenth of May." "Were your wife's parents present?" "Yes."

Next the young woman was questioned, and announced the marriage as having taken place in Brussels, some time in June, and that she is an orphan. The case is very plain, and both will have to face the court of special inquiry.

A young Jewish girl who really escaped the torment of some Russian persecutions conjures up in her mind a relative in New York whose name and address are not discovered, and the more she is questioned the more she entangles herself in a network of lies.

A dear old mother is held, because instead of the one son who awaits her, she has announced three or four sons residing here; and continued questioning more and more involves her in useless affirmation.

The examination can be superficial at best; but the eye has been trained and discoveries are made here, which seem rather remarkable.

Immigrants being inspected at Ellis Island circa 1910. Photo by Underwood & Underwood.

Four ways open to the immigrant after he passes the inspector. If he is destined for New York he goes straightway down the stairs, and there his friends await him if he has any; and most of them have.

If his journey takes him westward, and there the largest percentage goes, he enters a large, commodious hall to the right, where the money-changers sit and the transportation companies have their offices.

If he goes to the New England states he turns to the left into a room which can scarcely hold those who go to the land of the pilgrims and puritans.

The fourth way is the hardest one and is taken by those who have received a ticket marked P. C. (Public Charge), which sends the immigrant to the extreme left where an official sits, in front of a barred gate behind which is the dreaded detention-room.

The decision one way or the other must be quickly made, and the immigrant finds himself in a jail-like room often without knowing just why. There is not much time for explanation.

Imagine a room filled by at least fifty people, many of them doomed to recross the terrible sea and to be landed upon strange territory, to find the way unattended, to their obscure little village.

When they arrive there they are usually paupers with -a stigma resting upon them; for were they not rejected in America, and why ? Ah, who knows why !

Let us pass through this room. "Brotherwhy are you here?" A stalwart Lettish peasant boy answers demurely, "Because I haven't money enough. I had some money and they stole it out of my father's pockets."

The father and the boy have been marked by the inspector as likely to become a public charge, because they had neither money in their pockets nor friends waiting for them. A matter of ten or twenty dollars is between these men and the fulfillment of all their desires.

The court may be lenient, but the father is old and the boy young and it is more than probable that they will both end their days on the rough Baltic, where society now is as turbulent as that northern sea.

A Servian peasant, browned by the hot sun which shone upon the Danubian plains where he lived, edges up to me, for he hears a familiar Slavic note in my speech, and he brings this bitter plaint.

How far I have travelled from Budapest, Vienna, Berlin, and Hamburg. I have spent all my money and now it looks as if I must go back. "Must I go? Tell me."

The court will tell him to-morrow that he has passed the dreaded dead line, is over fifty years of age, not too well built, used up by the hardships of his native country, and that as he is likely to become a public charge he is marked for deportation. He will be sent back to Hamburg and how he will find his way home I do not know.

A German woman with three children is the next whom I notice. She is at the point of a nervous breakdown. She has a husband waiting for her, she has over $100, but P.C. is marked on her slip; so she must face the court which will admit her, but she has a long twenty-four hours to wait and the strain is terrible. She needs to be reassured and comforted.

Two boys under ten years of age came unattended; fine looking boys. Over their heavy blue coats hung tickets with the mother's address. How happy they were to be going to mother.

She had preceded them by several years to work out for herself and for them a new destiny on this side of the sea; for on the other side life had been blighted by the unfaithfulness of her husband.

At last the hour came when she could send for her children. How she watched their journeying, and how anxious she was while they were on the sea !

They are on this ship, and she is waiting for them behind the iron grating at the island. Crowds pour into the great hall, past the physician, towards the inspectors, towards the great centre, to the east and the west.

Now she sees them; the physician looks at their faces, and bends low over their chests; but instead of walking straight towards her they are turned aside with those suspected of contagious disease.

" Where are you from, my boy?" "Russia."

One of the few real Russian peasants whom I have met. He measures five feet six inches, is sound as an oak, and having escaped through the cordons of gendarmes which separate his native country from the rest of the world, came here to meet his brother who was at work in the coal mines near Scranton, Pa.

" What about your brother?" " Ah ! Barin (sir), my brother they say, was killed in the mines and they are afraid to let me in; so I suppose I shall have to go back to Russia," and the big melancholy peasant cried like a baby. " Buy this shirt from me, Barin, I need money."

" What's the matter with you, why are you so unhappy, you gay, care free Roumanian?" Half Slav, half Latin, and the whole no one quite knows what, -- he is dressed in a shepherd's garb, a heavy sheepskin coat over him. "

Look here, Panye (sir). This keeps me from going as a shepherd to the West; " and he shows me a lacerated breast on which a wolf has written the shepherd's story of his faithfulness to the sheep.

" Yes, the wolves came round and round my sheep," he says, " and I went round and round between the sheep and the wolves and the nearer they came the faster I went my rounds between them; but before the morning came they tore many sheep though they tore me first.

I bled and bled and have remained sore as you see. A younger shepherd took my place and I sold all and spent all to come here. Ah, well, I could still guard the sheep."

The most melancholy of all men are the detained Jews, for they usually have strong family ties which already bind them to this new world, and they chafe under the delay.

Their children or friends are waiting impatiently, crowding beyond their allotted limit, trying the severely taxed patience of the officials, asking useless questions, and wasting precious time in waiting; for the courts work their allotted tasks with dispatch, but with care and dignity; and all must wait in deep uncertainty through the long vigil of a restless night spent on the clean, but not too comfortable bunks provided by the government.

Let no one believe that landing on the shores of " The land of the free, and the home of the brave " is a pleasant experience; it is a hard, harsh fact, surrounded by the grinding machinery of the law, which sifts, picks, and chooses; admitting the fit and excluding the weak and helpless.

Much ignorance needs to be dispelled regarding these immigrants. Not long ago, I heard one of the secretaries of a certain home missionary society say, with much unction as he pleaded for money for his work,

" We land annually on these shores, a million paupers and criminals." Unfortunately, much of such impression prevails. It was my privilege recently, as a member of the National Conference on Immigration, to be among the guests of the commissioner of the port of New York, and one of the spectacles which we witnessed was the landing of a ship-load of immigrants.

We stood in the visitor's gallery and looked down upon a hall divided and subdivided by the cold iron railings. Many of the visitors were beginning to hold their noses in anticipation of the stenches which would come with these foreigners, and were ready to be shocked by the horrors of the .

Slowly the bewildered mass came into view; but strange to relate, those who led the mass appeared like ladies and gentlemen.

The women wore modern, half acre hats a little the worse for wear, but bought in the city of Prague a few months before; and they were more becoming to these young Bohemian women than to the majority of their American sisters.

The men carried band-boxes, silk umbrellas and walking canes, the remnants of past glories. They were permitted to come in first because they wore good clothing and passed out quickly into their freedom, the members of our Congress welcoming them heartily by the clapping of hands.

After them came Slavic women with no finery except their homespun, rough, tough and clean; carrying upon their backs piles of feather-beds and household utensils.

Strong limbed men followed them in the picturesque garb of their native villages; Slovaks, Poles, Roumanians, Ruthenians, Italians, and finally, Russian Jews; but lo, and behold ! no smells ascended to our nostrils, and no horrors were disclosed.

Taking a group of delegates down among them, we found that they were wholesome looking people, not devoid of intelligence, and when the barrier between us was broken down by the sound of their native speech, they were communicative, at ease, and very human.

The first time I entered New York was at Castle Garden, from the steamer Fulda, twenty years ago; and having watched the tide of immigration ever since, I can say that I never have seen, at any time, a ship-load of better human beings disembark than those which came from the steamer Wilhelm II, on December 7, 1905.

And of the many who came on this ship, it is just possible that those who wore neither fashionable hats nor trailing skirts, and who were not politely treated, -- it is just possible that they may after all, make the best members of this democratic society.

A gentleman from Ohio, a member of the Conference on Immigration said on the floor, in open debate, and he said it with menacing gesture : " We don't want you to send none of them yellow worms from Southern Europe to our state, we got too many of them now."

No doubt the gentleman from Ohio and the delegate from Rhode Island who said : " We don't want no more iv thim durrty furriners in this grand and glorious counthry of ourn," voiced the common prejudice which rests itself entirely upon its ignorance.

It is true that many criminals come, especially from Italy. Many weak, impoverished and poorly developed creatures come from among Polish and Russian Jews, but they are only the tares in the wheat.

The stock as a whole is physically sound; it is crude, common peasant stock, not the dregs of society, but its basis. Its blood is not blue, but it is red, wholesomely red, which is more to the purpose.

Blue blood we also receive -- thin, worn-out blood, bought at a high price for the daughters of some of our multimillionaires; but no one can claim that either they or we have been specially blessed by it.

The hardships which attend the examination and deportation of immigrants seem unavoidable, and would not be materially reduced if any other method were devised. To examine them at the centres of immigration seems a rather vague and not a feasible plan.

First of all because the immigrant can present himself as physically fit, more easily in his native country where the agencies already exist, to prepare him for an examination which most steamship companies rigidly enforce; because the long journey makes artificial cleansing of diseased eyelids or the hiding of other physical defects impossible.

Again because of the fact that such commissions would be hard to control so far from home and would be in constant danger of exposure to " Graft "; a disease not unknown among American officials at home and abroad.

The next reason is, that these countries might object to the presence of such alien commissions, which would select the best material and leave the worst; and the last reason is that it would give foreign governments a very fine opportunity to detain those who emigrate for political reasons or those who desire to avoid service in the army.

Much greater responsibility should be put upon the steamship companies, many of which still practice their ancient wrongs upon their most profitable passengers. One of the demands which should be made, and made immediately, is the abolition of the steerage.

Future American citizens should be taught when they step on board of ship, that people in America are expected to live like human beings, and not like beasts.

The price they pay for their passage is large enough to entitle them to better treatment, and if it is not, then the price should be raised to such a figure as to permit it.

This humane treatment should follow the passenger until the last moment of his stay under government supervision; for the more humanely the immigrant is treated, the better citizen he is likely to become.

The is responsible for not a little imported anarchy, and the sooner it is abolished the better. The more humanely the immigrant is treated at Ellis Island, the more humanely he will deal with us when he becomes the master of our national destiny.

The Man at the Ellis Island Gate

" What questions will he ask? " " How much money will he take ?" " Will he deal gently with us ?" These are the questions which pass from lip to lip among those detained; for the subjects of the Czar speak of the State in the personal pronoun. In fact the State is scarcely known in their vocabulary.

It is the person of the ruler which they know, and which they fear more than they revere. The State they have known, was to them very personal; but to the new State, they are just so much human freight which needs to be inspected.

In the past this has been done not only impersonally but inhumanely as well, and that it is now done more humanely and justly so far as possible, we owe to " the man at the gate."

He passed through the gate himself in the old Castle Garden days, when not much system prevailed, when boarding-house keepers were let loose upon us, frightening us half out of our senses and completely out of our change.

His dollars were few; but like the average immigrant of today he possessed a buoyant spirit, a strong body, keen wits, and bright eyes out of which shone good nature and the spirit of the mischievous boy.

He was admitted without difficulty, and drifted into Pennsylvania where he shared the lot of the miner, his labour and his dangers. The miners then were recruited from the strongest immigrant stock and when they felt themselves strong enough to organize, he became one of the leaders.

AT THE GATE With tickets fastened to coats and dresses, the immigrants pass out through the gate to enter into their new inheritance, and become our fellow citizens. From stereograph copyright-1904, by Underwood & Underwood, NY.

The fact that he led many a rescue party to save his entombed comrades, and that he displayed courage and intelligence brought him into prominence, and the Governor of Pennsylvania chose him as State Factory Inspector.

In this position he made enemies enough among the employers to prove that he was faithful to the task set before him, which was, to enforce the laws regulating the conditions of labour in workshops and factories.

Later he was appointed inspector at Ellis Island at a time when the condition of that federal post was anything but pleasing to those of us who knew them, and who were concerned for the well-being of the immigrant.

Roughness, cursing, intimidation and a mild form of blackmail prevailed to such a degree as to be common. The commissioner in charge at that time was far above all this, and though made conscious of the conditions was seemingly powerless to discharge dishonest employees or in any way improve the morale of the place.

The new spirit had not yet come into politics and the spoils still belonged to the victors who made full use of the privilege. Among those who did their full duty and who smarted under the wrong done to this weak and helpless mass, was the once immigrant, now inspector.

The conditions steadily grew worse; at least the complaints grew more numerous. Experiences like my own were not rare. I knew that the money changers were " crooked," so I passed a twenty mark piece to one of them for exchange, and was cheated out of nearly seventy-five per cent, of my money. My change was largely composed of new pennies, whose brightness was well calculated to deceive any newcomer.

At another time I was approached by an inspector who, in a very friendly way, intimated that I might have difficulty in being permitted to land, and that money judiciously placed might accomplish something.

A Bohemian girl whose acquaintance I had made on the steamer, came to me with tears in her eyes and told me that one of the inspectors had promised to pass her quickly, if she would promise to meet him at a certain hotel.

In heartbroken tones she asked : " Do I look like that?" The concessions were in the hands of irresponsible people and I remember the time when the restaurant was a den of thieves, in which the immigrant was robbed by the proprietor, whose employees stole from him and from the immigrant also.

My complaints when I made them were treated with the same neglect as were those of others, until with the coming in of the Roosevelt administration they had their resurrection, a change was demanded and the demand satisfied. . . .

Mr. William Williams, who was just back from Cuba where he had rendered distinguished service, and who had come under the notice of the President, was tendered the office of Commissioner of Immigration at Ellis Island.

Upon his acceptance, the President's instructions were to " clean out the stables." A large measure of reform was inaugurated during the two and one half years of Mr. Williams's incumbency of this office.

In looking for a successor, the President consulted the records, evidently with the purpose of discovering one thoroughly conversant with the conditions, and of experience coupled with executive ability, sufficient to further extend the needed reforms. Mr. Robert Watchorn was chosen for this important office.

This official announcement in relation to the appointment appeared in the daily press at this time :

"Washington, January 16, 1905.

" Robert Watchorn will succeed William Williams as United States Commissioner of Immigration at New York.The appointment will be solely on merit. Mr. Watchorn is now United States Commissioner of Immigration at Montreal. He has been in the immigration service for many years, and his record is perfect."

I ventured to ask the Commissioner one day if he had been given any instructions by the President as to the course to be pursued. He replied : " Yes, the President gave me instructions very brief but very pointed. Mr. Watchorn, I am sending you to Ellis Island. -- You will find it a very difficult place to manage. -- I know you are familiar with the conditions. -- All I ask of you is that you give us an administration as clean as a hound's tooth.' "

Should one desire any further evidence that Ellis Island is a difficult place to manage, let him turn to this incident and its sequel in Senator Hoar's " Autobiography of Seventy Years " (Scribner's):

During the Christmas holidays of 1901 a very well-known Syrian, a man of high standing and character, came into my son's office and told him this story :

a neighbour and countryman of his had a few years before emigrated to the United States and established himself in Worcester. Soon afterwards, he formally declared his intention of becoming an american citizen.

After a while, he amassed a little money and sent to his wife, whom he had left in Syria, the necessary funds to convey her and their little girl and boy to Worcester. She sold her furniture and whatever other belongings she had, and went across Europe to France, where they sailed from one of the northern ports on a German steamer for New York.

Upon their arrival at New York it appeared that the children had contracted a disease of the eyelids, which the doctors of the Immigration Bureau declared to be trachoma, which is contagious, and in adults incurable. It was ordered that the mother might land, but that the children must be sent back in the ship upon which they arrived, on the following Thursday.

This would have resulted in sending them back as paupers, as the steamship company, compelled to take them as passengers free of charge, would have given them only such food as was left by the sailors, and would have dumped them out in France to starve, or get back as beggars to Syria.

The suggestion that the mother might land was only a cruel mockery. Joseph J. George, a worthy citizen of Worcester, brought the facts of the case to the attention of my son, who in turn brought them to my attention. My son had meanwhile advised that a bond be offered to the immigration authorities to save them harmless from any trouble on account of the children.

I certified these facts to the authorities and received a statement in reply that the law was peremptory, and that it required that the children be sent home; that trouble had come from making like exceptions theretofore; that the Government hospitals were full of similar cases, and the authorities must enforce the law strictly in the future.

Thereupon I addressed a telegram to the Immigration Bureau at Washington, but received an answer that nothing could be done for the children.

Then I telegraphed the facts to Senator Lodge, who went in person to the Treasury Department, but could get no more favourable reply. Senator Lodge's telegram announcing their refusal was received in Worcester Tuesday evening, and repeated to me in Boston just as I was about to deliver an address before the Catholic College there.

It was too late to do anything that night. Early Wednesday morning, the day before the children were to sail, when they were already on the ship, I sent the following dispatch to President Roosevelt :

" To the President,

"White House, Washington, D. C." I appeal to your clear understanding and kind and brave heart to interpose your authority to prevent an outrage which will dishonour the country and create a foul blot on the American flag. a neighbour of mine in Worcester, Mass., a Syrian by birth, made some time ago his public declaration for citizenship. He is an honest, hard-working and every way respectable man. His wife with two small children have reached New York.

" He sent out the money to pay their passage. The children contracted a disorder of the eyes on the ship. The Treasury authorities say that the mother may land but the children cannot, and they are to be sent back Thursday. ample bond has been offered and will be furnished to save the Government and everybody from injury or loss.

I do not think such a thing ought to happen under your administration, unless you personally decide that the case is without remedy. I am told the authorities say they have been too easy heretofore, and must draw the line now. That shows they admit the power to make exceptions in proper cases.

Surely, an exception should be made in case of little children of a man lawfully here, and who has duly and in good faith declared his intention to become a citizen.

The immigration law was never intended to repeal any part of the naturalization laws which provide that the minor children get all the rights of the father as to citizenship.

My son knows the friends of this man personally and that they are highly respectable and well off. If our laws require this cruelty, it is time for a revolution, and you are just the man to head it. GEORGE F. HOAR."

Half an hour from the receipt of that dispatch at the White House Wednesday forenoon, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States, sent a peremptory order to New York to let the children come in.

They have entirely recovered from the disorder of the eyes, which turned out not to be contagious, but only caused by the glare of the water, or the hardships of the voyage. The children are fair-haired, with blue eyes, and of great personal beauty, and would be exhibited with pride by any American mother.

When the President came to Worcester he expressed a desire to see the children. They came to meet him at my house, dressed up in their best and glorious to behold. The President was very much interested in them, and said when what he had done was repeated in his presence, that he was just beginning to get angry.

The result of this incident was that I had a good many similar applications for relief in behalf of immigrants coming in with contagious diseases. Some of them were meritorious, and others untrustworthy. In the December session of 1902 I procured the following amendment to be inserted in the immigration law.

" Whenever an alien shall have taken up his permanent residence in this country and shall have filed his preliminary declaration to become a citizen and thereafter shall send for his wife and minor children to join him, if said wife or either of said children shall be found to be affected with any contagious disorder, and it seems that said disorder was contracted on board the ship in which they came, such wife or children shall be held under such regulations as the Secretary of the Treasury shall prescribe until it shall be determined whether the disorder will be easily curable or whether they can be permitted to land without danger to other persons; and they shall not be deported until such facts have been ascertained."

Senator Hoar had touched however, only one of the many phases of the situation. As the President said, it was still " a difficult place." Yet under Commissioner Watchorn changes were soon visible.

The place became cleaner; a new and better system of inspection was organized, discipline was maintained and strengthened, the comfort of the immigrants was considered, the money changers were watched, dishonest, discourteous and useless employees were discharged; and above all, the institution in its remotest corner was open to any one who wished to come and inspect the place which is so important in our economic and social life.

Heartier welcome than the Commissioner gives to the visitor cannot be imagined; and you may take your place among the dozen or more who have come and who are watching him as he decides the destinies of human lives.

The cases which come before him are those upon which the special courts have already passed; so you will see only the wreckage of humanity; those who upon landing are barred by a law which is indefinite enough to leave the way open to human judgment for good or ill.

Two undersized old people stand before him. They are Hungarian Jews whose children have preceded them here, and who, being fairly comfortable, have sent for their parents that they may spend the rest of their lives together.

The questions, asked through an interpreter, are pertinent and much the same as those already asked by the court which has decided upon their deportation.

The commissioner rules that the children be put under a sufficient bond to guarantee that this aged couple shall not become a burden to the public, and consequently they will be admitted.

A Russian Jew and his son are called next. The father is a pitiable looking object; his large head rests upon a small, emaciated body; the eyes speak of premature loss of power, and are listless, worn out by the study of the Talmud, the graveyard of Israel's history. Beside him stands a stalwart son, neatly attired in the uniform of a Russian college student.

His face is Russian rather than Jewish, intelligent rather than shrewd, materialistic rather than spiritual. " Ask them why they came," the commissioner says rather abruptly. The answer is : " We had to."

" What was his business in Russia ?" " A tailor."

" How much did he earn a week ?" " Ten to twelve rubles."

" What did the son do?" " He went to school."

" Who supported him ?" " The father."

" What do they expect to do in America?" " Work."

" Have they any relatives ?" " Yes, a son and brother."

" What does he do ?" " He is a tailor."

" How much does he earn? " " Twelve dollars a week."

" Has he a family?" " Wife and four children."

" Ask them whether they are willing to be separated; the father to go back and the son to remain here ?"

They look at each other; no emotion as yet visible, the question came too suddenly. Then something in the background of their feelings moves, and the father, used to self-denial through his life, says quietly, without pathos and yet tragically, "