Steerage Conditions Observed on the Cunard Line - 1881

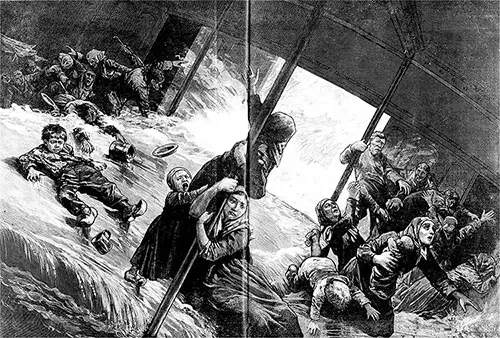

Steerage Passengers Terrified by Rough Weather circa 1880. GGA Image ID # 14787c02bb

I selected the Cunard line because I knew less of the habits of other vessels. This Line has lost two ships, but during forty years it is reputed not to have lost a passenger. This furnishes a sense of security which is very profitable to the line and diminishes the sickness among many voyagers.

Travelers, however, have assured me that more space and comfort are to be found in the ships of some other lines. The Cunards travel in a prescribed path, and have the merit of not caring to outrace other vessels, and will even take a day or two longer rather than incur risk. They act upon the principle that it is better for passengers to be late than be lost. A good imagination is a powerful quality at sea.

Many passengers become sick by suffering their eyes to rest upon the waves, as the sea appears to mount and fall around them. I was surprised to find that the officers and sailors of the Cunard Ships, to whose skill and watchfulness passengers owe much of their security, do not receive higher wages than men in other vessels.

On the second Sunday of a voyage, a collection is made for the widows and orphans of seamen. These ought to be provided for otherwise, after the manner of the Bill lately passed in Parliament for the compensation of workmen who suffer injury or loss of life in their employment, and the subscription made on board should be given to the ordinary sailors there and then, to whose good seamanship it mainly owes that you are alive to subscribe at all.

Sailing, as a rule, is attended with no more risk to life than railway traveling, and since the facilities for sailing increase every year, the time is not far distant when everybody will sail somewhere. A good book, therefore, upon the "Art of being a Sea Passenger" would be as useful as one on the Art of Swimming.

Out at sea, some persons prefer a rolling motion to the heaving; some can sleep over the screw (which I could do myself, although it seemed to be grinding under my pillow). A ship has such a variety of motion and sound that the passenger can take a choice.

The stoutest disciple of Dr. Darwin is generally content with the fertility of evolution on the ocean. So many people have got to go to sea that the nature of the going ought to be explained.

In the steerage, where the heaving is greatest-that part of the ship often rises out of the water and, of course, goes down again-sickness is prevalent; yet children recover from sickness much sooner than their parents, probably because they know less about it and do not make themselves miserable by gratuitous imagination.

While their parents are pale and apprehensive, I saw the children delighted at being rolled about the deck and nobody doing it. The drollery of that diverted them significantly. In the saloon, when passengers first see the storm fences on the table, they lose their appetite for the repast; the children think it very comical and eat with a new sense of pleasure.

A voyage is indeed a source of recreation and diversion of mind beyond what any who have never made a journey imagine. Ideas are often absolutely suspended.

“Dirty" weather comes and discolors them; "nasty" weather perturbs them; “fresh" weather gives them quite a new turn; a rain" squall" comes and softens them; a "gale" disperses them; a "storm" dashes them against each other, bending them or breaking them; a "cyclone" gives a rotary motion to the most fixed ideas; a "hurricane" seems to blow them all finally away, and it is sometime before the most diligent shepherd of his thoughts gets them into the old fold again.

The machinery of the mind is unlimbered, and only the best fitting parts are ever got into position again. It is thus that the ocean is entertaining and re-creative; the fresh wind blows through your mind.

Cries of sailors, straining of cordage and planks, creaking of the stubborn masts, beatings of the" steely sea," the roar of the revengeful blast, the clanking of the iron slaves within-I regarded as companions of the voyage. All the while, the brave engines are driving you through the turbulent and disappointed waves. Three hundred and fifty miles in every day and night,

The pulses of their iron hearts

Go beating through the storm

The passage between England and Ireland, I was told, would prove unpleasant, but that when we got into the Atlantic, the sailing would improve.

When we reached Queenstown, the more experienced passengers observed that we should know how to appreciate the serenity of the Irish passage, when we had a taste of the "roll of the Atlantic," which was very encouraging.

Every day brought some promise of novelty. Until I was on the Atlantic, I had never seen the sea alive. I had heard of" seas as smooth as glass." What I saw was a sea as smooth as mountains.

The Atlantic is a genuine American ocean; it is never still. The white crests of the waves appeared to me like white birds coming over the distant waters. It was quite a new experience to see dark clouds a great distance before us, where rain and squall were raging, and know that we had to sail through them; and when in a squall which appeared at first as though it would last always, we could soon see the sun and blue sky a long way off, and it was pleasant to discover that we should ride into the bright sea under them.

If a storm did not extend over an area of sixty miles, we were through it in four hours, unless head· winds blew. The screw of the vessel was then half out of the water, albeit the headwinds generally did blow with us.

Concerning the Treatment of Poor Steerage Passengers

In consequence of what was said in the "Pall Mall Gazette" concerning the treatment of poor steerage passengers of the Cunard Line, I went over the steerage quarters, both in the "Bothnia" and the "Gallia."

It was admitted by the writer of the complaints in the "Pall Mall" that the passengers in the Cunard fared better, as to quarters and diet than in other vessels. I went around the ship with Dr. Johnson, the medical officer of the "Bothnia."

The occupants of the steerage include many rough unmanageable people, whose habits often justify some coercion for the sake of the comfort of others. But I ascertained from those who knew, that the general comfort for the steerage passengers is not what it ought to be, or what it might be. Either Parliament or the press should compel improvements in the arrangement of the steerage.

When reporters visit a new vessel to report upon its equipment, they should look into the steerage arrangements. If our naval architects who seek distinction in rendering vessels shot-proof, would give attention to rendering them discomfort, proof for the emigrants who crowd the steerage, it would be a great blessing.

Mr. Vere Foster and Mrs. Chisholm secured many attentions to poor passengers, but the attention wanted is a different construction of the ship. In parts of the ship where comfort abounds, there is the eccentricity of contrivances.

For instance, the name-plates on Cunard doors were so low that it was only by going down upon your knees that a passenger could read them. Only a passenger who had broken his leg could find out the doctor's door.

Recurring to the steerage, Dr. Johnson said he commonly found poor women who came on board with families, and with one suckling at the breast, were generally in such a state of weakness as to be entirely unable to bear the strain of rough weather; and I saw myself orders given for dozens of porter and gallons of milk, whereby the more impoverished women and children were strengthened.

This was additional to the supply ordered by law, and were given at discretion by the kind-hearted doctor, who said the company never interfered with him in these things, and that in many cases, in the ships of this line, emigrants lived better than they had been accustomed to at home, which may be true of other lines also.

If American ships took as many steerage passengers to Great Britain as Great Britain takes to America, there would soon be new devices in the arrangement of ships.

George Jacob Holyoake, "Sea Ways and Sea Society," in Among the Americans and A Stranger in America, Chicago: Belford, Clarke & Co, 1881, Pages 18-23