Adventures In The Steerage - 1906

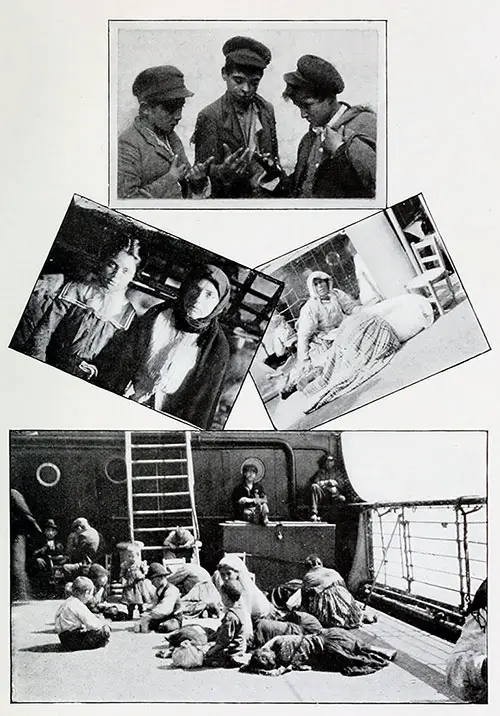

Mid Voyage Scenes in Steerage. Mora; Syrian Jews; Prostrated by the Swell; Children Escaping Seasickness. Broughton Brandenburg, Imported Americans 1904. GGA Image ID # 146068995f

"The steerage pays the ship," one sometimes hears aboard the Mediterranean and Adriatic service boats. This, like most epigrams, points if it does not state a truth. The fact lies between the steerage and saloon rates and the steerage and saloon service. There is a striking disproportion.

In connection with an investigation of the Italian immigration question, I was recently called upon to make a steerage passage to Naples and return. Going out, I traveled in a Cunard ship, paying $30 for my passage. Returning, I took passage in a White Star liner, paying 180 lire, or approximately $36 for my ticket.

First-class passage in either ship could be obtained for $90, and sometimes, it is possible to get first-class passage on Cunard steamers for $75. The difference in rate, therefore, was as two and a half to one or three to one.

The difference in service, however, showed a discrepancy so startling that a conservative writer hesitates to estimate it.

I will not generalize or theorize. I will state plain facts of my personal experiences on both steamers. On the Cunard ship, the "Pannonia," somewhat more than 500 passengers ate in one shared room, in which there were sixty occupied berths. For six days and six nights, we had very rough weather.

Many of the occupants of those berths were seasick. Sitting at the table, some passengers could almost touch the berths where these seasick passengers were located.

Suppose one-third of the occupants of these berths in full view of the dining tables were seasick. In that case, the effect on the other passengers may be readily pictured, not to mention the sight and smell of food upon those affected.

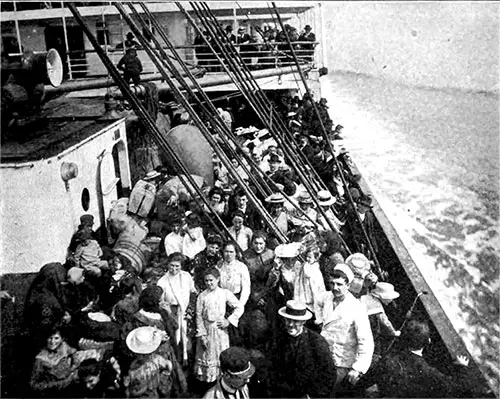

Five Hundred to Starboard, Five Hundred to Port Make an Ordinary Steerage Complement. Photo Courtesy of the International Mercantile Marine. Leslie's Monthly Magazine, May 1904. GGA Image ID # 14614e17f4

First Cabin Passengers Find Amusement in Watching the Crush of Steerage Passengers below. Photo Courtesy of the International Mercantile Marine. Leslie's Monthly Magazine, May 1904. GGA Image ID # 14618cb9e3

On the westward bound trip, when the ship's capacity is taxed. I am told that the number is increased from sixty to two hundred, sometimes. If these steerage passengers had a different social and educational status, no such condition as this would be imposed upon them. The steerage capacity of that ship is about 2,200.

It can hardly be possible that the fare of those passengers, who are forced to sleep in the dining rooms in full view of the entire ship, is necessary for the profitable running of the ship.

If it is, there is something radically wrong with the ship's management. If ten beds, or one bed, were put up in the saloon dining room, and a seasick passenger put therein for just one meal, the company's patronage would be jeopardized.

But these steerage passengers are not English-speaking as a rule, nor lettered. They are primarily ignorant peasant folk - Italians, Croatians, Dalmatians, Carpathians, Greeks and Syrians.

They do not pay $90 for their passage, but they do pay $30 for their tickets or $36 if they are coming to or going from an Adriatic port.

Ignorant though they are, poor as they are, uncouth perchance as they may appear, they do not enjoy this sort of thing any more than would saloon passengers.

It is just as difficult for a Greek or Italian peasant woman to keep her food close to the smells and sickening scenes of seasick passengers as for a well-bred lady whose punctilious daintiness is made mainly possible through the cheap labor of the peasant woman or her husband.

In the saloon, a hair on the butter might quickly spoil the meal of a nice $90 passenger. I have picked two giant, fat worms from one plate of macaroni on the White Star ship, been consoled by a fellow passenger, an Italian laborer, not to mind such things, and eaten the macaroni because I had to.

I do not mean to insinuate that all of the macaroni was wormy. Still, the incident, as I have stated, is a fact, and on more than one occasion, I have found small macaroni worms. I have seen other things picked out of the food by my fellow passengers.

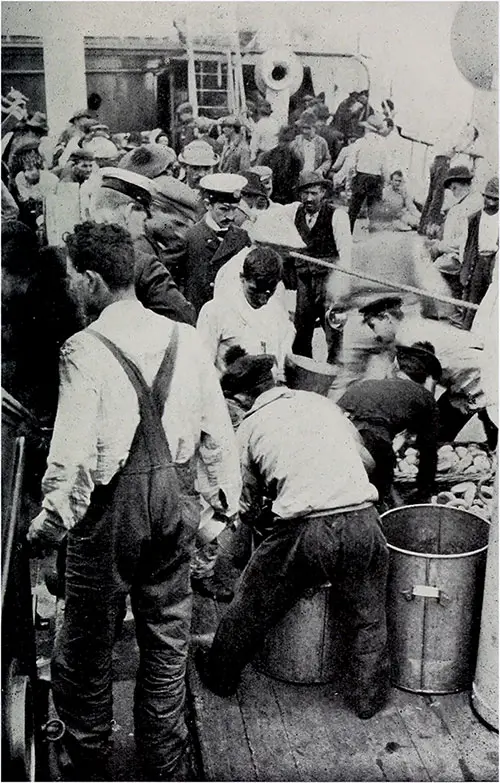

Preparing to Serve a Meal to Steerage Passengers on the Lahn from the Food Tanks and Bread Baskets. Broughton Brandenburg, Imported Americans 1904. GGA Image ID # 1460613e26

On the Cunard ship, passengers eat, sleep, and are sick in the same room. On the White Star ship, there was no dining room at all provided. The only sitting room or lounging room would not hold above 100, or, at the very utmost, 150 passengers on a ship carrying more than 2,000.

On this ship, there was no meal service whatever. At the feeding hours could scarcely be called meal times, great bell sounds and the chosen leaders of messes-capo di rancios-of every six or eight passengers line up in the passageway, leading off from which is the galley. Just over the galley threshold stand the stewards and galley cooks with vast food tanks.

As each mess leader steps up with an ordinary dishpan extended, one of the galley cooks drops into the pan the portion of the six or eight whom this mess leader represents.

The man then rejoins his group wherever they may be and divides the food. The meal is eaten, as a rule, at the spot where this apportionment takes place, or each man may shift for himself.

This means that the food is consumed from off a hatch, or in a corner on the floor, or on a deck, or in one's berth. A more unsatisfactory, and, in some particulars, a filthier scheme could scarcely be devised by human ingenuity.

Unsatisfactory as that is to the passengers, it suits the company. Otherwise, they would improve upon it or substitute another scheme. After these "meals," they clutter and refuse to lie in profusion over everything.

The typical immigrant is still an uneducated child. What he cannot cat or does not want, he lets fall from his hands. He has not yet learned the desirability of tidiness, and there is nothing in the ship's system to encourage this instinct if it perchance exists. He has yet to learn to throw his waste over the ship's rail instead of dropping it to the deck.

I realize that an ocean steamship company is not a reform school, a social settlement, or a philanthropic agency. Still, when it is remembered that the first notion of American life is conceived by these immigrants from their treatment on the ship, it is a matter of concern to America and Americans that the steamship companies introduce specific systems of service that suggest some degree of decency and civilization.

At the port of embarkation at Naples, I was given what is known as my "gear." Sometimes, this gear is handed out to the passengers. In my case, I found my gear on my bunk.

This gear consists of a tin saucepan, a tin cup, and a tin fork and spoon-no knife. At some meals, large chunks of meat are doled out. It is expected that these shall be speared with a fork and nibbled.

The only other alternative I could discover was to do as some of my fellow passengers did-wrestle to separate these chunks of meat into manageable sizes by holding them with their forks and hacking at the meat with jack knives or stilettoes.

When there are a few individuals left over from the regular assorted mess, they go to the galleys with their pans. As it is necessary to make but a single trip for the food, it is often a complex matter to get the food to one's bunk if that is the place one has chosen for consuming his food.

At the first meal that I received on this ship, while I tried to balance a plate of soup in one hand and a dipper of wine in the other, a cob or biscuit was dropped into my soup, there being no other way of carrying it, and occasionally, when a large slice of goat's milk cheese would be given us with our meal, a cook or steward would balance the piece of cheese on the edge of my plate, which, at the first lurch of the ship, or sometimes at the first step I took, would slide into my soup and repose there until I got to my bunk.

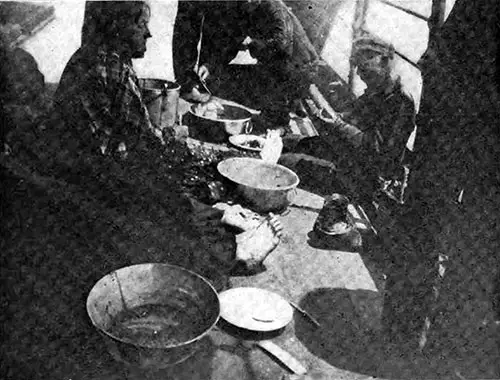

Serving Meals to the Passengers in Steerage -- How Not to Do Meals. The Home Missionary, January 1908. GGA Image ID # 146846ccea

Sometimes, we hear the steerage passengers referred to in slighting and uncomplimentary words on the promenade deck. Most of us who have crossed the ocean in the saloon have listened to such phrases now and again dropped by spick and span gentlemen and ladies to whom fine silver and white linen are a part of their day's necessities even on shipboard, just as much as the clothes on their backs or the boots on their feet.

As a steerage passenger, I did not always conduct myself in a manner that would have become a proper dining room, but was that my fault? How can steerage passengers, or how can any human being remember that he is a human being when he must first pick the worms from his food, haggle his meat with a jack knife, and eat in his stuffy, stinking bunk or in the hot and fetid atmosphere of a compartment where 150 men sleep, or in juxtaposition to a seasick man?

The imposition ends with this rough form of feeding. Having eaten-(bountifully perchance, for there is always enough of such as it is. I don't think I ever succeeded in eating all of the meat or all of the macaroni that was given me) each passenger must wash their dishes; at least, so I found it on my White Star ship. The provisions made for this by the company would interest a New England homemaker.

The Result of Having No Dining Room Accommodations in Steerage. The Home Missionary, January 1908. GGA Image ID # 1468505274

There is a large and ample supply of raw, cold seawater, which is obtained in unlimited quantities by simply turning a faucet. There are two small metal tubs in one section of the ship about three-quarters the size of an ordinary wash tub, where men may rinse their dishes. These tanks sometimes, but only sometimes, have warm water.

But they are so small, and the crowds surge so about them, that I never could force my dishes into them, so had to be content to let the salt water run over them from the faucet, and then when I could get to it, I either scraped my dishes with my fingernails or a bit of paper, which I sometimes tore from a bundle.

Towels, dishcloths, or drying cloths were, of course, not provided. The Cunard Company washes the dishes of passengers, as it allows for dining tables or dining halls, and serves the meals correctly. I must frankly own that my dishes were always very much cleaner when done by the Cunard Steamship Company than when on the White Star boat, I had to do my washing.

As to the food itself, I would not complain. On the whole, despite an occasional worm, the macaroni was all right. It was very monotonous fare, to be sure, but still, it was cooked correctly. On the Cunard ship, there was a variety and a tastiness, which the steerage cook frequently attained through types of sauces, which made the eating tolerable.

The Italian Government insists that a commissario accompany each ship sailing from an Italian port carrying passengers. This commissario comes to the steerage galley before each meal and samples the food. If he does not like it, it is all thrown overboard.

This ensures that the food is cooked. There is a good deal of farce connected with this ceremony, however, for my chief complaint is not against the food so much as against the service.

When the commissario appears, a clean white napkin is spread over an end of a galley table. The food is served to him on proper china, and his wine is not in a battered tin dipper but in an ordinary glass. Of course, the food is not poison; it is simply rough and cheap. Macaroni every day for twelve or fourteen days does not appeal to one unaccustomed to that diet.

Yet it is unnecessary one should starve. The point is, why should the steamship companies charge $30 or $36 for this sort of fare and service when for two or three times that amount, one can travel so comfortably in the class known as the saloon?

Here, for example, is a fair comparison between a Sunday dinner in the steerage and a Sunday dinner in the saloon. These bills are taken as they came the same day on the same ship, the Cunard ship.

THIRD-CLASS BILL OF FARE.

Dinner.- Vegetable Soup.

- Beef, Pork and Sauerkraut Goulash.

- Beef and Macaroni Stew.

- Jacket Potatoes.

- Stewed Prunes. Figs.

- Fresh Bread. Biscuit. Wine.

It should be noted that the passengers still need to receive both goulash and stew. The former was for the Hungarian and Slavish section of the ship, the latter for the Italians.

What the dinner amounted to was a bowl of soup, a plate of stew with boiled potatoes, stewed prunes served in a tin saucepan, one for about every five or six passengers, and two or three tiny figs doled out by hand by the stewards.

The usual crude red wine, about one-third water, with a cob, or what in America would be called a bun, made up this Sunday feast. With this, compare the saloon dinner, bearing in mind that the saloon passengers paid, or at least some of them, at most three times steerage fare.

SALOON DINNER.

- Hors d'Otuvres, varies.

- Pert au Feu. Mulligatawny

- Fillet of Flounder. Shrimp Sauce, Lobster à la Newburgh.

- Turtle Steaks, Montpelier. Salmi of Game.

- Sirloin of Beef. Potato Croquettes.

- Lamb. Mint Sauce. Round of Corned Beef.

- Vegetables.

- Boiled Chicken, Béchamel Sauce.

- Boiled Purée à la Julienne Potatoes.

- Boiled Rice.

- Baked Tomatoes. Fried Egg Plant.

- Roast Capon, Bread Sauce.

- Cold Roast Beef. Boiled Ham.

- Roast Turkey.

- Salad.

- Cabinet Pudding.

- Almond Macaroons. Gateau à la Richmond.

- Wine Jelly. Peaches à la Conde.

- French Ice Cream-Wafers.

- Canapes à la Windsor.

- Cheese. Dessert. Coffee.

The cost and worth of the latter is considerably greater than three times that of the former. If, therefore, the saloon rate is fair, then the steerage rate at one-third of the saloon rate is grossly out of proportion, unfair, and unjust in the 'light of food received and service rendered by the one class in proportion to the other.

Suppose the service rendered to saloon passengers is so complete and so good that there is only a narrow margin of profit. In that case, the inference is that the broader margin in the steerage service increases this margin.

On the other hand, if the steerage rate is a fair one, then the saloon rate is so low that the service must be maintained at a loss so that, viewed from whatever side, there is a flagrant maladjustment.

The meals on the Cunarder were always of the simplest stew, macaroni, and "salads" mostly. It should be emphasized that the Cunard fare was distinctly better in quality and variety than the White Star ship, or at least it was according to my taste.

Food on shipboard is at a higher market value than on land. Still, in New York during the month of my trip to Naples, it would have been possible to supply some of the meals that we received for 4 or 5 cents per head.

To be safe, to give the company the benefit of the most remote shadow of the doubt, we may double that amount, make liberal allowances in the striking of our average, and assume that the cost is 10 cents per meal per head. There were about forty meals served.

The aggregate cost of all the meals, then, service not included, would reach $4. It must be emphasized again that the complaint is neither against the quality nor the quantity of the food. It is against an unfair scale of charges and certain conditions incompatible with our present-day civilization.

Further, at Ellis Island, I found the dining room service very much better than on either the Cunard or White Star ship; I found the food better, and there was plenty of it.

It was well served, and the stewards were courteous. When I was held in the detention room simply as an ordinary immigrant, I did what any immigrant might do: I asked for second helpings and always received them without question. And yet I am informed that the amount allowed for his food is about 24 cents a day.

To compare the steerage and saloon conditions further, let us consider the sleeping arrangements. A saloon stateroom ordinarily accommodates four persons.

There are clean sheets, white blankets, and tidy spreads on the beds. Clean white towels are furnished. There are washing facilities in every room.

Passenger in Steerage on Board an Emigrant Ship at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Photo Courtesy of Den Norske Amerikalinje. GGA Image ID # 1fc336c315

Ordinarily, none of these things are considered luxuries hopelessly out of the reach of even people experiencing poverty. In the room where I slept in the steerage, going over, there were about 150 passengers.

There were compartments on the ship with accommodations for many more than this number. The bunks were in double tiers of iron piping with simple iron springs. Returning strips of sheet iron or some metal took the place of springs.

The mattresses were burlap bags of straw on the Cunard line, covered with a simple tick; on the White Star ship, uncovered. On both boats, the pillows were the same life preserver placed under one end of the mattress to give it a slight elevation.

For covering, passengers on both boats were given one thin blanket. We all slept in our clothes as a matter of course.

The atmosphere in these compartments, after a few days, becomes excessively close and fetid. One Italian workingman told me that he slept in his bunk but one night out of thirteen-preferring to sleep on the deck the other twelve nights.

The washing facilities on both boats could have been more pleasant. On the Cunard boat, the washing facilities needed to be improved. There were five lavatories for men and two for women. In the large lavatories were twelve basins; in the smaller ones, seven.

The lavatories were exceedingly small and cramped, so these places were packed, jammed to the doors, an hour before breakfast.

I stood my turn sometimes in a row three or four back of the basins and nearly suffocated before I got out of the closed room. Many regularly only pretended to wash after breakfast. Indeed, the rush immediately before breakfast made any other arrangement impossible. These seven lavatories were for the use of 2,200 steerage passengers.

Sometimes, and, indeed, on the return trip regularly, the men near me and I filled a wine bottle with water each night. In the morning, we poured this water over each other's hands and thus made our assisted toilets.

The saloon passengers have the advantage of a library, a smoking room, ample decks, and lounging places.

In times of storm, when the passengers are ordered within or below, the steerage has nowhere to save to their berths or the tiny, hopelessly inadequate lounging room of the White Star ship or to the dining room of the Cunard so that the atmosphere, wherever these passengers are herded, soon becomes sickening.

At every point, the comparison between the saloon and the steerage shows a difference of many degrees. The attitude of some of the ship's officers, again, is characterized by ill temper and caddishness.

Here, however, I would hasten to add that I do not believe for an instant that either of these companies would approve or permit any act of discourteous treatment on the part of their officers.

The last English officer on the Cunard ship frequently went out of his way to make himself obnoxious to steerage passengers. On the White Star ship, I saw one of the senior officers snatch up a bundle that an immigrant had dropped upon a coil of rope and hurl it at the head of the owner, accompanying it with a volley of oaths, simply because the immigrant, entirely ignorant, had unsuspectingly placed the bundle on a coil of rope which happened to be needed by the officer for immediate use.

To have removed the bundle or kicked it aside would have been justifiable. Still, this officer would not have cursed a saloon passenger. For even this offense, he certainly would not have thrown his luggage at his head.

But this is an attitude of which the companies themselves would heartily disapprove. At the same time, it must be considered that these outbreaks of temper and exhibitions of caddishness on the part of individual officers are a part of the steerage imposition, which the majority of steerage passengers accept as a matter of course, and when abused slink away like whipped dogs.

It is because the steamship companies represent business enterprises that it is the duty of the American people to take up matters like these. As business concerns, the steamship companies owe allegiance, first to their owners and stockholders, afterward to their saloon passengers, then to their second class passengers, and finally to the steerage.

Therefore, the Government needs to watch, regulate, and facilitate conditions for the comfort, health, and safety of the travelers who are steamship steerage patrons.

The Italian and Hungarian Governments have looked into specific questions, have imposed certain regulations upon the steamships, and have provided officers and commissioners to accompany vessels carrying their citizens or other people to their countries. As a consequence of this, the food on the Mediterranean and Adriatic boats comes up to a certain standard.

If the American Government would take up the service, the benefit that would accrue to thousands of immigrants annually would be great.

The living conditions aboard these ships have yet to be adequately investigated or at least taken up. The commissioners and officers representing the Italian and Hungarian Governments cannot do more than inspect the general cleanliness of the ship.

It remains for our Government to do something here. Steerage conditions are vastly better today than they were a few years ago. Yet much remains to be done to promote better sanitary and more comfortable conditions on all vessels engaged in the immigrant-carrying trade.

If human beings are to be subjected to treatment and conditions proper for cattle, then they should be taken at freight or livestock rates; or. on the other hand, if they are to be called passengers and charged a substantial passenger rate, then they should have the consideration of such. American citizens clearly must ask their Government to consider these matters, for these people will, many of them, someday be American citizens.

Durland, Kellogg, "Steerage Impositions," in The Independent, Vol. LXI, No. 3013, New York, Thursday, August 30, 1906, P. 499-504

Mr. Dorland has just returned from a trip to Naples and back, where he went as a steerage passenger to investigate immigration and kindred topics. We are glad to give some of his experiences and impressions to our readers.-Editor

Kellogg Durland (1881-1911), a popular American journalist in the 1900s-1910s, is the author of The Red Reign: The True Story of a Year in Russia (New York, 1907), which included interviews with Tolstoy; it was the most widely known book on Russia and Russian conditions written by an American of the time, after George Kennan’s books on Siberia and the exile system. Durland spent all of the year 1906 and part of 1907 in the empire of the Czar. It was at this time that he visited Count Tolstoy at his home, Yasnaya Polyana.