US Immigration Report On Steerage Conditions - 1911

Steerage Passengers at the Bow of the SS Frederich der Gross circa 1915. Bain Collection, Library of Congress # 2014707273. GGA Image ID # 145f5b3048

The report of the Immigration Commission on steerage conditions resulted from investigations by agents of the Commission who, in the guise of immigrants, traveled in the steerage of 12 trans-Atlantic ships.

Practically all of the more essential lines engaged in the immigrant-carrying traffic were included in the inquiry, and every type of steerage was studied. The report upon this subject was presented to Congress on December 13, 1909, and printed as Senate Document No. 26, Sixty-first Congress, second session.

It is reprinted here as a part of the Commission’s complete report to the Congress. Miss Anna Herkner, who, as an agent of the Commission, crossed the Atlantic three times as a steerage passenger, prepared the report on steerage conditions.

Introduction to Immigration Commission Report

Prior to the act of 1819, “Regulating passenger ships and vessels,” (Note a) there was no law of the United States for the protection of passengers at sea.

In 1796, Congress, at the instance of States having seaports, passed a law directing revenue officers “to aid in the execution of the quarantine and also in the execution of the health laws of the States.” (Note b)

Again, in 1799, it was decreed by Congress “ that quarantine and other restraints which shall be required and established by the health laws of any State or pursuant thereto, respecting any vessels * * * shall be duly observed by the collectors and other officers of the revenue o the United States.” (Note c)

These laws were intended to protect persons already in the country rather than those journeying to or from it in ships, but the act of 1819, above referred to, was the first national legislative attempt to improve conditions surrounding immigrants during the then long voyage across the Atlantic.

This law limited the number of passengers to be carried and specified the amount and kind of food to be provided. It is of interest also that under this law the recording of data relative to immigration to the United States was first provided for.

The introduction of steam as a motive power in ocean transportation and the enormous increase in the tide of immigration necessitated further legislation relative to the transportation of immigrants, the history of which is told in a special report of the Commission upon that subject.“ (Note d)

The latest general revision of the law upon this subject occurred in 1882, when “An act to regulate the carriage of passengers by sea ” (Note e) was enacted. Section 1 of this act was subsequently amended, (Note f) but otherwise it has remained unchanged.

The unamended act of 1882 was in force when the Immigration C0mmission’s investigation of steerage conditions was made.

There has never before been thorough investigations of steerage conditions by national authority, but such superficial investigations as having been made, and the many nonofficial inquiries as well, have invariably disclosed evil and revolting conditions.

The high percentage of sickness and death, which attended immigration by sea during the sailing-vessel period, has been practically eliminated by reducing the length of time required for the voyage, and perhaps also in part by the greater precautions in this regard taken by steamship companies; but improvements along other lines are much less conspicuous.

The steerage on some ships at the present time is entirely unobjectionable, but both unobjectionable and revolting steerage conditions may and do exist on the same ship.

It is the purpose of this report to show steerage conditions precisely as they were found, but, what is of more importance, it will also show that there is no reason why the disgusting and demoralizing conditions, which have generally prevailed in the steerages of immigrant ships, should continue.

This has been amply demonstrated by experiences of the Commission’s agents, and the Commission believes that the better type of steerage should and can be made general instead of exceptional, as is the case at the present time.

The report on steerage conditions is based on information obtained by special agents of the Immigration Commission traveling as steerage passengers on 12 different trans-Atlantic steamers and on observation of the steerage in 2 others, as well as on ships of every coastwise line carrying immigrants from one United States port to another.

Because the investigation was carried on during the year 1908, when, owing to the industrial depression, immigration was very light, the steerage was seen practically at its best.

Overcrowding with all its attendant evils was absent. What the steerage is when travel is heavy, and all the compartments filled to their entire capacity can readily be understood from what was actually found. In reading this report, then, let it be remembered that not extreme but comparatively favorable conditions are here depicted.

Note a: 1 U. S. Stat. L., p. 54, sec. 4 (Resume from Note a)

Note b: 1 U. S. Stat. L., p. 474 (Resume from Note b)

Note c: 1 U. S. Stat. L., p. 619 (Resume from Note c)

Note d: See Steerage Legislation, 1819-1908. Reports of the Immigration Commission, vol. 40 (Resume from Note d)

Note e: Appendix A (Resume from Note e)

Note f: Appendix B (Resume from Note f)

The Old Steerage - 1911

The Old and New

Transatlantic steamers may be classed in three general subdivisions on the basis of their provision for other than cabin passengers. These are:

- Vessels Having the Ordinary or Old-Type Steerage

- Those Having the New-Type Steerage

- Ships Containing Both Types

To clarify the distinction between these subdivisions, a description of the two types of steerage, old and new, will be given.

The Old Conditions

The old-type steerage is the one whose horrors have been so often described. It is unfortunately still found in a majority of the vessels bringing immigrants to the United States.

It is still the common steerage in which hundreds of thousands of immigrants from their first conceptions of our country and are prepared to receive their first impressions of it.

The universal human needs of space, air, food, sleep, and privacy are recognized to the degree now made compulsory by law. Beyond that, the persons carried are looked upon as so much freight, with mere transportation as their only due. The sleeping quarters are large compartments, accommodating as many as 300 or more persons each.

For assignment to these, passengers are divided into three classes, namely, women without male escorts, men traveling alone, and families.

Each class is housed in a separate compartment, and they are often located in different parts of the vessel. It is generally possible to shut off all communication between them, though this is not always done.

Sleeping Arrangements

The berths are in two tiers, with an interval of 2 feet and 6 inches of space above each. They consist of an iron framework containing a mattress, a pillow, or more often a life preserver as a substitute, and a blanket. The mattress and the pillow, if there is one, are filled with straw or seaweed.

On some lines, this is renewed every trip. Either colored gingham or coarse white canvas slips cover the mattress and pillow. A piece of iron piping placed at a height where it will separate the bedding is the “partition” between berths. The blankets differ in weight, size, and material on different lines.

On one line of steamers, where the blanket becomes the property of the passenger on leaving, it is far from adequate in size and weight, even in the summer. Generally, the passenger must retire almost fully dressed to keep warm.

Through the entire voyage, from seven to seventeen days, the berths receive no attention from the stewards. The berth, 6 feet long and 2 feet wide and with 24 feet of space above it, is all the space to which the steerage passenger can assert a definite right. To this 30 cubic feet of space, he must, in no small measure, confine himself.

No space is designated for hand baggage. As practically every traveler has some bag or bundle, this must be kept in the berth. It may not even remain on the floor beneath. There are no hooks on which to hang clothing.

Everyone, almost, has some better clothes saved for disembarkation, and some wraps for warmth that are not worn all the time, and these must either be hung about the framework of the berth or stuck away somewhere in it.

At least two large transportation lines furnish the steerage passengers eating utensils and require each one to retain these throughout the voyage. As no repository for them is provided, a corner of each berth must serve that purpose.

Towels and other toilet necessities, which each passenger must furnish for himself, claim more space in the already crowded berths. The floors of these large compartments are generally of wood, but others consist of large sheets of iron were also found.

Sweeping is the only form of cleaning done. Sometimes the process is repeated several times a day. This is particularly true when the litter is the residue of food sold to the passengers by the steward for his own profit.

No sick cans are furnished, and not even large receptacles for waste. The vomit of the seasick is often permitted to remain a long time before being removed. The floors, when iron, are continually damp, and when of wood they reek with foul odor because they are not washed.

Open Deck Areas

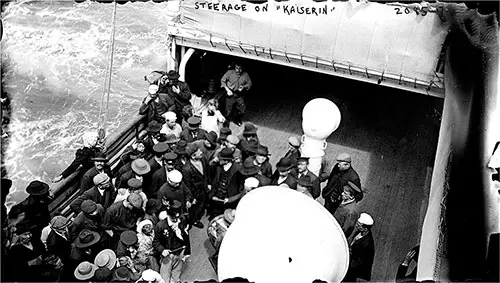

Steerage Passengers on the Deck of the SS Kaiserin Auguste Victoria circa 1906. Bain Collection, Library of Congress # 2014688582. GGA Image ID # 145fcd88e2

The open deck available to the steerage is very limited, and regular separable dining rooms are not included in the construction. The sleeping compartments must, therefore, be the fixed abode of a majority of the passengers.

During days of continuous storms, when the unprotected open deck cannot be used at all, the berths and the passageways between them are the only space where the steerage passenger can pass away the time. When to this minimal space and much filth and stench is added inadequate means of ventilation, the result is almost unendurable.

Its harmful effects on health and morals scarcely need be indicated. Two 12-inch ventilator shafts are required for every 50 persons in every room, but the conditions here are abnormal, and these provisions do not suffice.

The air was found to be invariably unhealthy, even in the higher enclosed decks where hatchways afford further means of ventilation. In many instances persons, after recovering from seasickness, continue to lie in their berths in a sort of stupor, due to breathing air whose oxygen has been mostly replaced by foul gases.

Those passengers who make a practice of staying much on the open deck feel the contrast between the air out of doors and that in the compartments, and consequently find it impossible to remain below long at a time. In two steamers, those who could no longer endure the foul air between decks always filled the open deck long before daylight.

Washrooms and Lavatories

Washrooms and lavatories, separate for men and for women, are required by law, which also states they shall be kept in a “clean and serviceable condition throughout the voyage.”

The indifferent obedience to this provision is responsible for further uncomfortable and unsanitary conditions.

The cheapest possible materials and construction of both washbasins and lavatories secure the smallest possible degree of convenience and make the maintenance of cleanliness extremely difficult where it is attempted at all.

The number of washbasins is invariably by far too few, and the rooms in which they are placed so small as to admit only by crowding as many persons as there are basins.

The only provision for counteracting all the dirt of this kind of travel is cold salt water, with sometimes a single faucet of warm water to an entire washroom.

Also, in some cases, this faucet of warm water is at the same time the only provision for washing dishes. Soap and towels are not furnished.

Floors of both washrooms and water closets are damp and often filthy until the last day of the voyage when they are cleaned in preparation for the inspection at the port of entry. The claim that it is impossible to establish and maintain order in these parts of the immigrant quarters is thus shown to be false.

Dining Areas

Regular dining rooms are not a part of the old type of steerage. Such tables and seats as the law says “shall be provided for the use of passengers at regular meals” are never sufficient to seat all the passengers, and no effort to do this is made by systematically repeating the seating arrangements.

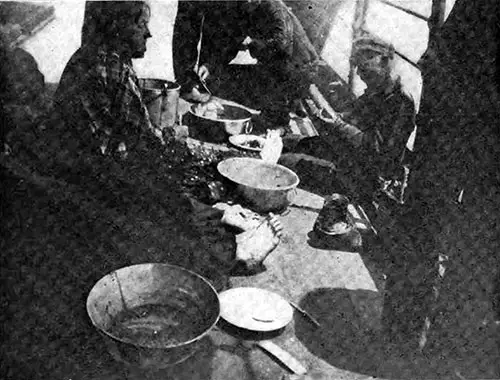

Serving Meals to the Passengers in Steerage -- How Not to Do Meals. The Home Missionary, January 1908. GGA Image ID # 146846ccea

In some instances, the tables are little shelves along the wall of a sleeping compartment. Sometimes plain boards set on wooden stools and rough wooden benches placed in the passageways of sleeping compartments are considered compliance with the law.

Again, when a compartment is only partly full, the empty space is called a dining room and is used by all the passengers in common, regardless of what sex uses the rest of the compartment as sleeping quarters.

When traffic is so light that some compartment is entirely unused, its berths are removed and stacked in one end and replaced by rough tables and benches.

This is the amplest provision of dining accommodations ever made in the old type steerage and only occurs when space is not needed for other more profitable use.

Food and Dining

There are two systems of serving the food. In one instance the passengers, each carrying the crude eating utensils given him to use throughout the journey, pass in single file before the three or four stewards who are serving and each receives his rations.

The Result of Having No Dining Room Accommodations in Steerage. The Home Missionary, January 1908. GGA Image ID # 1468505274

Then he finds a place wherever he can to eat them, and later washes his dishes and finds a hiding place for them where they may be safe until the next meal.

Naturally, there is a rush to secure a place in line and afterward a scramble for the single warm-water faucet, which has to serve the needs of hundreds. Between the two, tables and seats are forgotten or they are deliberately deserted for the fresh air of the open deck.

Under the new stem of serving, women and children are given the preference at such tables as there are, the most essential eating utensils are placed by the stewards and then washed by them.

When the bell announces a meal, the stewards form in a line extending to the galley and large tin pans, each containing the food for one table, are passed along until every table is supplied. This constitutes the table service.

The men passengers are even less favored. They are divided into groups of six. Each group receives two large tin pans and tin plates, cups, and cutlery enough for the six; also one ticket for the group.

Each man takes his turn in going with the ticket and the two large pans for the food for the group, and in washing and caring for the dishes afterward. They eat where they can, most frequently on the open deck. Stormy weather leaves no choice but the sleeping compartment.

The food may generally be described as fair in quality and sufficient in quantity, and yet it is neither; fairly good materials are usually spoiled by being wretchedly prepared. Bread, potatoes, meat, and when not old leavings from the first and second galleys, form a reasonably substantial diet.

Coffee is invariably bad, and tea doesn’t count as food with most immigrants. Vegetables, fruits, and pickles form an insignificant part of the diet and are generally of very inferior quality.

The preparation, the manner of serving the food, and disregard of the proportions of the several food elements required by the human body make the food unsatisfying, and therefore insufficient.

This defect and the monotony are relieved by purchases at the canteen by those whose capital will permit. Milk is supplied for small children.

Treating Ill Passengers

Hospitals have long been recognized as indispensable, and so are specially provided in the construction of most passenger-carrying vessels. The equipment varies, but there are always berths and facilities for washing and a latrine closet at hand.

A general aversion to using the hospitals freely is very apparent on some lines. Seasickness does not qualify for admittance. Since this is the most prevalent ailment among the passengers, and not one thing is done for either the comfort or convenience of those suffering from it and confined to their berths.

Since the hospitals are included in the space allotted to the use of steerage passengers, this denial of the hospital to the seasick seems an injustice. On some lines, the hospitals are freely used. A passenger ill in his berth receives only such attention as the mercy and sympathy of his fellow-travelers supplies.

Order and Cleanliness

After what has already been said, it is scarcely necessary to consider the observance of the provision or the maintenance of order and cleanliness in the steerage quarters and among the steerage passengers separately.

Of what practical use could rules and regulations by the captain or master be when their enforcement would be either impossible or without tangible result with the existing accommodations?

The open deck has always been decidedly inadequate in size. The amendment to section 1 of the passenger act of 1882, which went into effect January 1, 1909, provides that henceforth this space shall be 5 superficial feet for every steerage passenger carried.

On one steamer, showers of cinders were a deterrent to the use of the open-air deck for several days. On another, a storm made the use of the open air deck impossible during half the journey. The only seats available were the machinery that filled much of the deck.

Crew Excluded from Passenger Compartments Except while Performing Duties

Section 7 of the law of 1882, which excluded the crew from the compartments occupied by the passengers except when ordered there in the performance of their duties, was found posted in more or less conspicuous places.

There was generally one copy in English and one in the language of the crew. It was never found in all the different languages of the passengers carried, yet they are as much concerned by this regulation as is the crew. And if passengers of one nationality should know it, it is equally essential that all should.

Conclusion

This old-type steerage considered as a whole, it is congestion so intense, so detrimental to health and morals that there is nothing on land to equal it. That people live in it only temporarily is no justification o its existence.

The experience of a single crossing is enough to change bad standards of living to worse. It is an abundant opportunity to weaken the body and implant their germs of disease to develop later.

It is more than a physical and moral test; it is a strain. Admittedly, it is not the introduction to American institutions that will tend to make them respected.

The standard plea that better accommodations cannot be maintained because they would be beyond the appreciation of the emigrant and because they would leave too small a margin of profit carry no weight. Since the desired kind of steerage already exists on some of the lines and is not conducted as either philanthropy or a charity.

The New Steerage

Nothing is striking in what this new-type steerage furnishes. On general lines, it follows the plans of the accommodations for second-cabin passengers.

The one difference is that everything is simpler proportionately to the difference in the cost of passage. Unfortunately, the new type of steerage is to be found only on those lines that carry emigrants from the north of Europe. The number of these has become but a small percent of the total influx.

The competition was the most potent influence that led to the development of this improved type of steerage and established it on the lines where it now exists.

A division, by mutual agreement, of the territory from which the several transportation lines or groups of such lines draw their steerage passengers lessens the possibility of competition as a force for the extension of the new type of steerage to all emigrant-carrying lines.

The legislation, however, may complete what competition began. The new-type steerage may again be subdivided into two classes. The best of these follows the plan of the second-cabin arrangements very closely; the other adheres in some respects to the old-type steerage.

These resemblances are chiefly in the construction of berths and the location and equipment of dining rooms. The two classes will not be considered separately, but the differences in them will be noted.

The segregation of the sexes in the sleeping quarters is observed under the law in the new type of steerage much more carefully than in the other.

Women traveling without male escort descend one hatchway to their part of the deck, men another, and families still another. Enclosed berths or staterooms secure further privacy.

The berths are sometimes precisely like those in the old-type steerage in construction and bedding. The best, however, is built the same as cabin berths.

The bedding was found sometimes less clean than others, but the blankets were always ample. Staterooms contain from two to eight berths. The floor space between the berths is utilized for hand baggage. On some steamers, special provision is made beyond the end of the berths for luggage.

There are hooks for clothes, a seat, a mirror, and sometimes even a stationary washstand and individual towels are furnished. Openings below and above the partition walls permit circulation of air.

Lights near the ceiling in the passageways give light in the staterooms. In some instances, there is an electric bell within easy reach of both upper and lower berths which summons a steward or stewardess in case of need.

On some steamers, stewards are responsible for complete order in the staterooms. They make the berths and sweep or scrub floors, as the occasion requires.

The most important thing is that the small rooms secure a higher degree of privacy and give seclusion to families. On most steamships, some large compartments still remain. Men passengers occupy these when traffic is heavy.

In spite of the less crowded conditions, the air is still bad. Steamers that were models in other respects were found to have air as foul as the worst. The lower the deck, the worse was the air.

Though bearing no odors of filth, it was heavy and oppressive. It gave the general impression of not being changed nearly often enough.

Those who were able to go up on the open deck, and thus experience the difference between fresh air and that below found it impossible to remain between decks long even to sleep. The use of the open-air deck generally began very early in the morning.

Where there are not stationary washstands in the staterooms and their presence is still the exception and not the rule, lavatories separate for the two sexes are provided.

These are generally of a size sufficient to accommodate comfortably even more persons than there are basins. Roller towels are provided, and sometimes even soap.

The basins are of the size and shape most commonly found everywhere. They may be porcelain and cleaned by a steward, or they may be of a coarse metal and receive little care. It is not found impossible to keep the floors dry during the entire journey.

The water closets are of the usual construction—convenient for use and not difficult to maintain in, a serviceable condition. Floors are at all times clean and dry.

Objectionable odors are destroyed by disinfectants. Bathtubs and showers are occasionally provided, though their presence is seldom advertised among the passengers, and a fee is a prerequisite to their use.

Food and Dining Rooms

Regular dining rooms appropriately equipped are included in the ship’s construction. Between meals, these are used as general recreation rooms.

A piano, a clock regulated daily, and a chart showing the ship’s location at sea may be other pieces of evidence of consideration for the comfort of the passengers.

On older vessels, the dining room occupies the center space of a deck, enclosed or entirely open, and with the passage between the staterooms opening directly into it; the tables and benches are of rough boards and movable.

The tables are covered for meals, and the heavy white porcelain dishes and proper cutlery are placed, cleared away, and washed by stewards. They also serve food.

On the newer vessels, the dining rooms are even better. In equipment, they resemble those of the second cabin. The tables and chairs are substantially built and attached to the floor.

The entire width of a deck is occupied. This is sometimes divided into two rooms, one for men, the other for women and families.

Between meals, men may use their side as a smoking room. The floors are washed daily. The desirability of properly eating meals served at tables and away from the sight and odor of berths scarcely needs discussion.

The dining rooms, moreover, increase the comfort of the passengers by providing some sheltered place beside the sleeping quarters in which to pass the waking hours when exposed to the weather on the open deck becomes undesirable.

The food overall is abundant and when adequately prepared Wholesome. It seldom requires reinforcement from private stores or by purchase from the canteen.

The general complaints against the food are that suitable material is often spoiled by poor preparation; that there is no variety and that the food lacks taste.

But there were steamers found where not one of these charges applied. Little children received all required milk. Beef tea and gruel are sometimes served to those who for the time being cannot partake of the usual food.

Health Care

Hospitals were found following the legal requirements. On the steamers examined there was little occasion for their use. The steerage accommodations were conducive to health, and those who were seasick received all necessary attention in their berths.

Along with the striking difference in living standards between old and new types of steerage goes a vast difference in discipline, service, and general attitude toward the passengers.

One line is now perhaps in a state of transition from the old to the new type of steerage. It has both on some of its steamers. It is significant that the emigrants carried in its two steerages do not look radically different in any way.

It is wholly unworthy of a transportation line that maintains such excellent new-type steerage to be content to still retain on its vessels the infamous old-type steerage.

The replacement of sails by steam and the consequent shortening of the ocean voyage has practically eliminated the problem of a high death rate at sea.

Many of the evils of ocean travel still exist, but they are not long enough continued to produce death. At present, the passing of a passenger on a steamship is the exception and not the rule.

A contagious disease may and does sometimes break out and bring death to some passengers. There are also other instances of death from natural causes, but these are rare and call for no particular study or alarm.

Inspection of Living Quarters

The examination of the steerage quarters by a customs official at our ports of entry to ascertain all the legal requirements have been observed is and in the very nature of things must be merely superficial. The inspector sees the steerage as it is after being prepared for his approval, and not as it was when in actual use.

He does not know enough about the plan of the vessel to make his own inspection, and so he only sees what the steerage steward shows him.

The time devoted to the inspection suffices only for a passing glance at the steerage, and the method-employed does not tend to give any real information, much less to disclose any violations.

These, then, are the forms of steerage that exist at the present time. The evils and advantages of such are not far to seek. The remedies for such atrocities as still exist are known and proven, but it still remains to make them compulsory where they have not been voluntarily adopted.

Recommendations by the Immigration Commission

As the new statute took effect so recently as January 1, and as the “new” steerage, in the opinion of all our investigators, fully complies with all that can be demanded.

The Commission recommends that a statute is immediately enacted providing for the placing of government officials, both men, and women, on vessels carrying third-class and steerage passengers, the expense to be borne by the steamship companies.

The Bureau of Immigration should continue the system inaugurated by the Commission of sending investigators in the steerage in the guise of immigrants at intervals.

In the past, no agent or employee of the bureau has ever crossed the Atlantic in the steerage, so far as the records show. The placing of government officials on the steamers will soon result in the abolition of the “old-style” steerage by legislation if necessary.

Legislation will be careful and comprehensive if based on the report of such officials as to steerage conditions when travel is reasonable, which it was not when the Commission’s investigations were made.

A Typical Old-Style Steerage: An Investigator's Report

While this report is long, a little over 6,000 words, it contains a snapshot of what it was really like crossing the Atlantic in the steerage class in 1908. The text was edited for spelling, grammar, and clarity to improve readability. Portions of the report were "redacted," and a "_____" was inserted to replace the redacted text.

Report of the Investigator

The statements in this report, unless otherwise indicated, are based on actual experiences and observations made during a twelve days’ voyage in the steerage of the ______ [ in the summer of 1908]

I arrived in ____ as a "single woman" in the disguise of a Bohemian peasant, under an assumed name, and with passage engaged in the steerage on the _____.

I called out the name of the agent from whom my ticket was purchased, ______, as directed in the circular sent me, and was approached by a porter, who carried my baggage and led me to ______ office.

From here, we were directed to a lodging house at which Bohemians and Moravians are usually lodged. Here I remained until my vessel sailed. The charges were 3 kroner a day for a clean bed and three meals—-a breakfast of coffee and rolls; a dinner of soup, boiled beef, potatoes, and another vegetable; and a supper of coffee, rye bread, and butter.

Later, on the steamer, other passengers told me of the places at which they had stopped. Some said the board had been much better than was being served on the ____.

Others complained that the landlords had tried to overcharge them, and when they rebelled, that half of the original bill was gladly accepted. No one could tell very definitely where he had lodged.

Each spoke of it as the agent’s, probably because he had been sent there by some clerk in the agent’s office.

During the day it was necessary to present myself at the agent’s office, pay the balance of my passage money, and give specific information about myself.

This consisted of my name, age, occupation, name and address of the people to whom I was going, name and address of nearest relative left behind, amount of money in my possession, nationality, last residence, whether married or single, and whether ever before in America.

Beyond this, no inquiries or investigation were made as to my literacy, my past, the source of my passage money, my morals, or mental condition. My ‘workbook ’ (Note a) which was to serve as my passport out of Austria, a counterfeit with a false and utterly blurred seal, was carefully examined, but no unfavorable criticism was offered.

On the day just before sailing all the steerage passengers who were not American citizens were vaccinated by the physician from the _____ and one other.

The women bared their arms in one room, the men in another. No excuse was sufficient to escape this requirement. However, the skin was not even pierced in any one of the three spots on my arm, and I later found this to be true in the case of many of the other passengers.

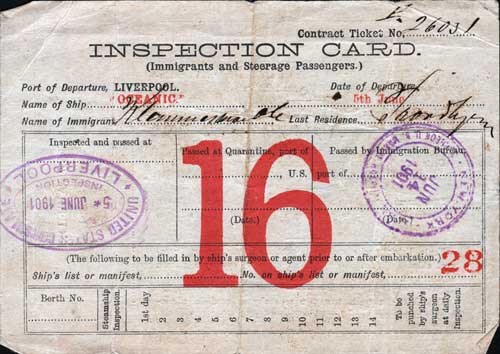

The eyes were casually examined by the same physicians. Each "inspection card" was stamped by the United States consulate and also marked ‘vaccinated.’

Sample Inspection Card of an Austrian Emigrant from 1912. Courtesy of the Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives. GGA Image ID # 1d8800f929

July 30 we went by train from ______to _____, wherein the waiting room we were classed as "families," "single women" — that is women traveling alone — and "single men," or men traveling alone. Thus subdivided we went on board, each class into a compartment especially assigned to it.

Living and Sleeping Quarters

The compartment provided for single women was in some respects superior to the quarters occupied by the other steerage passengers. It was likewise in the stern of the vessel, but was located on the main deck and had formerly been the second cabin. The others were on the first deck below the main deck.

All the steerage berths were of iron, the framework forming two tiers and having but a low partition between the individual berths. Each bunk contained a mattress filled with straw and covered with a slip made of coarse white canvas, apparently cleaned for the voyage.

There were no pillows. Instead, a life preserver was placed under the mattress at the head in each berth. A short and lightweight white blanket was the only covering provided.

This each passenger might take with him on leaving. It was practically impossible to undress properly for retiring because of insufficient covering and lack of privacy. Many women had pillows from home and used shawls and other clothing for covers.

Other conditions in our compartment were unusually good, owing to the small number of passengers, 36 instead of 194 in this particular section. We were not crowded, and there were better air and fewer odors. The vacant berths could be used as clothes racks and storage space for hand baggage.

Our compartment was subdivided into three sections—one for the German women, which was boarded entirely off from the rest; one for Hebrews; and one for all other creeds and nationalities together.

The partition between these last two was merely a fence, consisting of four horizontal 6-inch boards. This neither kept out odors nor cut off the view.

The single men had their sleeping quarters directly below ours, and adjoining was the compartment for families and partial families—that is, women and children.

In this last section, every one of the 60 beds was occupied, and each passenger had only the 100 cubic feet of space required by law.

The Hebrews were here likewise separated from the others by the same ineffectual fence, consisting of four horizontal boards and the intervening spaces. During the first six days, the entire 60 berths were separated from the rest of the room by a similar fence.

Outside the fence was the so-called dining room, getting all the bedroom smells from these 60 crowded berths. Later the spaces in, above, and below the fence were entirely boarded up.

The floors in all these compartments were of wood. They were swept every morning, and the aisles sprinkled lightly with sand. None of them was washed during the twelve days voyage nor was there any indication that a disinfectant was being used on them. The beds received only such attention as each occupant gave to his own.

When the steerage is full, each passenger’s space is limited to his berth, which then serves as bed, clothes and towel rack, cupboard, and baggage space.

There are no accommodations to encourage the steerage passenger to be clean and orderly. There was no hook on which to hang a garment, no receptacle for refuse, no cuspidor, no cans for use in case of seasickness.

Two washrooms were provided for the use of the steerage. The first morning out, I took special care to inquire for the women’s restroom. One of the crew directed me to a door bearing the sign "Washroom for men." Within were both men and women. Thinking I had been misdirected, I proceeded to the other washroom.

This bore no label and was likewise being used by both sexes. Repeating my inquiry, another of the crew directed me just as the first had done. Evidently, there was no distinction between the men’s and the women’s washrooms.

These were on the main deck and not convenient to any of the sleeping quarters. To use them one had to cross the open-air deck, subject to the public gaze. In the case of the families and men, it was necessary to come upstairs and across the deck to get to both washrooms and toilets.

The one washroom, about 7 by 9 feet, contained 10 faucets of cold salt water, 5 along either of its two walls and as many basins. These resembled in size and shape the usual stationary laundry tub.

Ten persons could scarcely have used this room at one time. The basins were seldom used on account of their great inconvenience and because of the various other services to which they must be put.

To wash out of a laundry tub with only a little water on the bottom is quite tricky, and where so many persons must use so few basins, one cannot take the time to draw so large a basin full of water.

This same basin served as at dishpan for greasy tins, as a laundry tub for soiled handkerchiefs and clothing, and as a basin for shampoos, and without receiving any special cleaning. It was the only receptacle to be found for use in the case of seasickness.

The space indicated to me as the ‘women’s washroom’ contained 6 faucets of cold salt water and basins like those already described. The hot-water faucet did not act.

The sole arrangement for washing dishes in all the steerage was located in the women's washroom. It was a trough about 4 feet long, with a faucet of warm salt water.

This was never hot, and seldom more than lukewarm. Coming up in single-file to wash dishes at the trough would have meant very long waiting for those at the end of the line.

To avoid this, many preferred cold water and washbasins. The steerage stewards also brought dishes here to wash. If there was no privacy in our sleeping quarters, there indeed was none in the washrooms.

Steerage passengers may be filthy, as is often alleged, but considering the total absence of conveniences for keeping clean, this uncleanliness seems but a natural consequence.

Some may really be filthy in their habits, but many make heroic efforts to stay clean. No woman with the smallest degree of modesty, and with no other conveniences than a washroom, used jointly with men, and a faucet of cold salt water can keep clean amidst such surroundings for twelve days and more.

It was forbidden to bring water or washing purposes into the sleeping compartments, nor was there anything in which to carry it. On different occasions, some of the women rose early, brought drinking water in their soup pails, and thus tried to wash themselves adequately, but were driven out when detected by the steward.

Others, resorting to extreme measures, used night chambers, which they carry with them for the children, as washbasins. This was done a great deal when preparation was being made for landing. Even hair was washed with these vessels. No soap and no towels were supplied.

Seeing the sign "Baths" over a door, I inquired if these were for the steerage. The chief steerage steward informed me that this sign no longer meant anything; that when that section had been used by the second cabin, the baths had been there.

"Are there then no baths for the steerage?” I asked. "Oh, yes; in the hospital," he assured me. “Where all the steerage may bathe?" I continued. “They are really only for those in the hospital, but if you can persuade the stewardess to prepare you a bath, I will permit you to have one," he replied.

The toilets for women were six in number—for men about five. They baffle description as much as they did use. Each room or space was exceedingly narrow and short, and instead of a seat, there was an open trough, in front of which was an iron step and back of it a sheet of iron slanting forward. On either side wall was an iron handle.

The toilets were filthy and difficult of use and were apparently not cleaned at all during the first few days. Later in the voyage, they were evidently cleaned every night, but not during the day.

The day of landing, when the inspection was made by the customs official who came on board, the toilets were clean, the floors in both bathrooms and washrooms were dry, and the odor of a disinfectant was noticeable. All these were conditions that did not obtain during the voyage or at any one time.

Each steerage passenger is to be furnished all the eating utensils necessary. These he finds in his berth, and as the blanket, they are in his possession and his care. They consist of a fork, a large spoon, and a combination of workingman's tin lunch pail.

The bottom or pail art is used for soup and frequently as a washbasin; a small tin dish that fits into the top of the container is used for meat and potatoes; a cylindrical projection on the lid is a dish for vegetables or stewed fruits; a tin cup that fits onto this projection is for drinks.

These must serve the passenger throughout the voyage and so are generally hidden away in his berth for safekeeping, there is no other place provided. Each washed his own dishes, and if he wished to use soap and a towel, he must provide his own.

Dishwashing is not an easy job, as there is only one faucet for warm water, and when there is no chance to use this, he has no other choice than to try to get the grease off of his tins with cold salt water.

As the ordinary man doesn’t carry soap and dish towels with him, he has not these aids to proper dishwashing.

He uses his hand towel, if he happens to have one, or his handkerchief, or must let the dishes dry in the sun. The quality of the tin and this method of washing is responsible for the fact that the dishes are soon rusty, and not fit to eat from.

Here, as in the toilet and washrooms, it would require persons of very superior intelligence, skill, and ingenuity to maintain order with the given accommodations.

The steamship company clearly complies with the requirement that tables for eating be supplied in the steerage, and in spite of efforts cannot make the steerage passengers use these tables.

Apparently, it is true that the immigrants did not make use of the conveniences provided. But where are these tables, and how convenient is it to eat at them?

The main steerage dining room was a part of a compartment on the first deck below the main deck. It contained seven long tables, each with two benches, and seating at most 12 persons. The remainder of the compartment included 60 berths closely crowded together, the sleeping quarters for families.

During the first few days, the partition between these crowded sleeping quarters and the dining room was but a fence made of four 6-inch boards running horizontally. Only later was this partition made a solid wall. Most people preferred the open deck to this dining room and its disagreeable odors.

A table without appointment and service means nothing. The food was brought into the dining room in large galvanized tin cans. The meat and vegetables were placed on the tables in tins resembling smaller sized dishpans. There were no serving plates, knives, or spoons.

Each passenger had only his combination dinner pail, which is more convenient away from a table than at it. This he had to bring himself and wash when he had finished. Liquid food could not be easily served at the tables, so each must line up for his soup and coffee.

No places at the table were assigned, and no arrangement made for two sittings, and as all could not be seated at once, the result denoted disorder, to escape which many left the dining room. Besides these seven tables, there were two on the main deck, in the sleeping compartments of the single women.

In the other two sleeping compartments, there were shelves along the wall and benches by the side of these. Including these, there was barely seating capacity for the small number in the steerage on this trip.

On inquiring where the passengers were seated when the steerage was crowded, I was told by the Hebrew cook and several others of the crew that then there was no pretense made to seat them. The attempt at serving-us at tables was soon given up.

If the steerage passengers act like cattle at meals, undoubtedly it is because they are treated as such. The stewards complain that they crowd like swine, but unless each passenger seizes his pail when the bell rings announcing the meal and hurries for his share, he is very likely to be left without food. No time is wasted in the serving.

One morning, wishing to see if it were possible for a woman to rise and dress without the presence of men onlookers, I watched and waited my chance.

There was none until the breakfast bell rang when all rushed off to the meal. I arose, dressed quickly, and hurried to the washroom. When I went for my breakfast, it was no longer being served.

The steward asked why I hadn’t come sooner saying, “The bell rang at 5 minutes to 7, and now it is 20 after. I suggested that twenty-five minutes wasn’t a long time for serving 160 people, and also explained the real reason for my tardiness. He then said that under the circumstances I could still have some bread.

However, he warned me not to use that excuse again. As long as no systematic order is observed in serving food in the steerage, the passengers will resort to the only effective method they know. Each will rush to get his share.

Breakfast always consists of cereal, coffee, white bread, and either butter or prune jam. In the afternoon, coffee and dried bread were served. The two Sundays we were out, this was changed to chocolate and coffee cake, which were quite good and much appreciated.

The dinners and suppers were as follows:

Thursday, July 30, [1908].—Dinner: Macaroni soup, boiled beef, potatoes, white bread. Supper: Stew of meat and potatoes, tea, black bread, and butter.

Friday, July 31, [1908].—Dinner: Lentil soup, boiled fish, potatoes, gravy, white # Supper: Hash (mostly potatoes), dill pickle, tea, black bread, and butter.

Saturday, August 1, [1908].—Dinner: Stewed liver, gravy, potatoes, stewed rice with dried apples and raisins, white bread. Supper: Boiled fish, potatoes, gravy, tea, black bread, and butter.

Sunday, August 2, [1908].—Dinner: Salt pork, potatoes, string beans, white bread. Supper: Sausage, potatoes, tea, black bread, butter.

Monday, August 3, [1908].—Dinner: Soup meat (evidently stewed leftovers of roasts), potatoes, white bread. Supper: Sauerkraut with liver (left over from Saturday), potatoes, tea, black bread, and butter.

Tuesday, August 4, [1908].—Dinner: Sausage, potatoes, a vegetable mixture, white bread. Supper: Pickled herring, potatoes, tea, black bread.

Wednesday, August 5, [1908].—Dinner: Soup, corned beef, potatoes, white bread. Supper: Mutton stew, cabbage, potatoes, tea, black bread, butter.

Thursday, August 6, [1908].—Dinner: Macaroni soup, meat with gravy, potatoes, lentils, raisin bread. Supper: Potatoes, with meat gravy, tea, black bread, butter.

Friday, August 7, [1908].—Dinner: Pea soup, either herring or meat with gravy, potatoes, cabbage, bread. Supper: Canned fish, potatoes, tea, black bread, butter.

Saturday. August 8, [1908].—Dinner: Vegetable soup, left-overs of roast, potatoes, white bread. Supper: Hash (mostly potatoes), pickle, tea, black bread.

Sunday, August 9, [1908].—Dinner: Soup, salt pork, potatoes, cabbage, bread. Supper: Sausage, potatoes, tea, black bread, butter.

Monday, August 10, [1908].—Dinner: Soup, beef, potatoes, string beans, white bread. Supper: Boiled eggs, fried potatoes, bread.

The Reality of the Meals Served

These menus sound well, and the allowances for each person were generous, but the quality and the preparation of much of the food were inferior. It is no doubt a complicated matter to satisfy so many persons of such varied tastes, but the passengers of the nationality of the line were as [vocal in] their complaints of this cooking as any of the others.

So simple a thing as coffee was not adequately prepared. I carefully watched the process by which it was made. The coffee grounds, sugar, and milk were put in a large galvanized tin can. Hot water, not always boiling, was poured over these ingredients. This was served as coffee.

The white bread, potatoes, and soup, when hot, were the only good foods, and these received the same favorable criticism from passengers of all nationalities.

The meats were generally old, tough, and smelled terrible. The same was true of the fish, excepting pickled herring. The vegetables were often a queer, unanalyzable mixture, and therefore avoided. The butter was often inedible.

The stewed dried prunes and apples were merely the refuse that is left behind when all the edible fruit is graded out. The prune jam served at breakfast, judging by taste and looks, was made from the lowest possible grade of fruit.

Breakfast cereals, a food foreign to most Europeans, were merely boiled and served in an abundance of water. The black bread was soggy and not at all like the good, wholesome, coarse black bread served in the cabin.

During the twelve days, only about six meals were fair and gave satisfaction. More than half of the food was always thrown into the sea. Hot water could be had in the galley, and many of the passengers made tea and lived on this and bread. The last day out we were told on every hand to look pleasant, else, we would not be admitted in Baltimore.

The Farewell Dinner

To help bring about this happy appearance the last meal on board consisted of boiled eggs, bread, and fried potatoes. Those who commented on this meal said it was "the best yet."

None of this food was thrown into the sea, but all were eagerly eaten. If this simple meal of ordinary food, well prepared, gave such general satisfaction, then it is really not so difficult after all to satisfy the tastes" of the various nationalities.

A few simple standard dishes of fair quality and adequately prepared, even though less generously served, would, I am positive, give satisfaction. The expense certainly would not be higher than that now caused by the waste of so much inferior food.

The interpreter, the chief steerage steward, and one other officer were always in attendance during the meals to prevent any crowding. When all had been served, these three walked about among the passengers asking: "Does the food taste good?" The almost invariable answer was: "it has to; we must eat something.’"

The Popular Bar

There was a bar at which drinks, fruits, candies, and other such things were sold. This was well patronized. Those who had any money to spare soon spent it at the bar—-the men for drinks, the women for fruit.

Several of them told me they only had to supplement the mediocre food, and in doing so had spent all they dared for apples and oranges at 3 cents apiece. Different stewards told me that 1,000 marks and more were taken in at the bar when travel was more substantial.

There was a separate galley and another cook for the preparation of kosher food for the Hebrews. They used the same tables with others if they used any, and were served in the same manner. Their diet also seemed of the same quality.

The Shipboard Hospital

The two clean, light, airy hospital rooms on the port side of the main deck, one for women, the other for men, made an excellent first impression. Each contained 12 berths in two tiers.

The iron framework was the same as that of all the steerage berths, but the beds had white sheets and pillows with white slips. By the side of each berth was a frame, holding a glass and a bottle of water. Also, a sick can. A toilet and bath adjoined each hospital.

The steerage stewardess, whose chief duties were distributing milk for little children, and giving out bread at meals, acted as nurse. According to her own statement, she had never had any training in the care of the sick. She spoke German and some English.

The interpreter, I was told, interprets for her and the doctor when it is necessary. However, when the doctor learned that I could speak both Slavic languages and German, he called on me to interpret for him in the case of each of his four Slavic patients.

On one occasion a 6-year-old girl was seized with violent cramps. The doctor ordered a hot bath, but the hot-water faucet gave forth nothing. The stewardess had to bring hot water from the galley across one deck, up the stairs, across another deck, and down other stairs.

Later he ordered a cold bath, which could be given only after another delay. The water ran so thick and filthy that it was not fit to use. There were no towels, and a sheet was used instead.

Aside from the berths and a washstand, there were no hospital conveniences or apparatus in the room. The most trivial articles had to be sent for to the ‘drug store’ at some distance.

At another time I had proof of the difficulty of getting the doctor to respond to a call. A Polish girl was suffering from severe pains in her chest and side. This was reported to a passing officer with the request that the doctor is sent.

Later the same request was made of the chief steward, and then of another officer. Finally, someone secured the stewardess, and she went for the doctor. In all more than two and one-half hours had elapsed between the time when the case was first reported and the doctor’s appearance. The doctor never was sympathetic, and when not indifferent was quite rough.

I remarked to this physician that I and many others were not going to have any vaccination mark to present, and I showed some fear of not being admitted at Baltimore. He assured me, with a smile of self-satisfaction, that the mark on the inspection card was the vital matter.

Inspection of Immigrants Onboard Ship

The daily medical examination of the steerage was carried on as follows: The second day out we all passed in single file before the doctor as he leisurely conversed with another officer, casting an occasional glance at the passing line. The chief steerage steward punched six holes in each passenger’s inspection card, indicating that the inspection for six days was complete.

One steward told me this was done to save the passengers from going through this formality every day. The fourth day out we were again reviewed. The doctor stood by. Another officer holding a cablegram blank in his hand compared each passenger’s card to some writing on it.

There was another inspection on the seventh day when we were required to bare our arms and show the vaccinations. Again, our cards were punched six times, and this completed the medical examination.

Just before landing, we were reviewed by some officer who came on board and checked us off on a counting machine operated by a ship’s officer.

In the women’s sleeping compartment, in an inconspicuous place, here hung a small copy of section 7, passenger act for 1882, in German and English. A similar copy hung in the so-called dining room.

Few of the women could read either of these languages. From the time we boarded the steamer until we landed, no woman in the steerage had a moment’s privacy.

The Lack of Privacy

One steward was always on duty in our compartment, and others of the crew came and went continually. Nor was this room a passageway to another part of the vessel. The entrance was also the only exit. The men who came may or may not have been sent there on some errand.

This I could not ascertain, but I do know that, regularly, during the hour or so preceding the breakfast bell and while we were rising and dressing, several men usually passed through and returned for no ostensible reason. If it were necessary for them to move so often, another passageway should have been provided or a more convenient time chosen."

“As not nearly all the berths were occupied, we all chose upper ones. To get anything from an upper berth or to deposit anything in it or to arrange it, it was necessary to stand on the framework of the one below. The women often had to stand thus, with their backs to the aisle.

The crew in passing a woman in this position never failed to deal her a blow—even the head steward. If a woman were dressing, they always stopped to watch her, and frequently hit and handled her. Even though they were sent there, this was not their errand.

Two of the stewards were quite strict about driving men out of our quarters. One other steward who had business in our compartment was as annoying a visitor as we had and he began his offenses even before we left port.

Some of the women wished to put aside their better dresses immediately after coming on board. As soon as they began to undress, he stood about watching and touching them. They tried to walk away, but he followed them.

Not one day passed, but I saw him annoying some women, especially in the washrooms. At our second and last inspection, this steward was assigned the duty of holding each woman by her bare arm that the doctor might better see the vaccination.

A small notice stating the distance traveled was posted each day just within the entrance to our compartment. It was the only one posted in the steerage as far as I could learn, and consequently, both crew and men passengers came to see it, and it served as an excuse for coming at all times.

The first day out the bar just within our entrance was used. This brought a large number of men into our compartment, many not entirely sober, but later the bar was transferred.

One night, when I had retired very early with a severe cold, the chief steerage steward entered our compartment, but not noticing me approached a Polish girl who was apparently the only occupant. She spoke in Polish, saying, "My head aches—please go on and let me alone."

But he merely stood on and soon was taking unwarranted liberties with her. The girl, weakened by seasickness, defended herself as best she could, but soon was struggling to get out of the man’s arms.

Just then, other passengers entered, and he released her. Such was the man who was our highest protector and court of appeal.

I cannot say that any woman lost her virtue on this passage, but in making free with the women, the men of the crew went as far as possible without exposing themselves to the danger of punishment. But this limit is no doubt frequently overstepped.

Several of the crew told me that many of them marry girls from the steerage. When I mentioned that they could scarcely become well enough acquainted to marry during the passage, the answer was that the acquaintance had already gone so far that marriage was imperative.

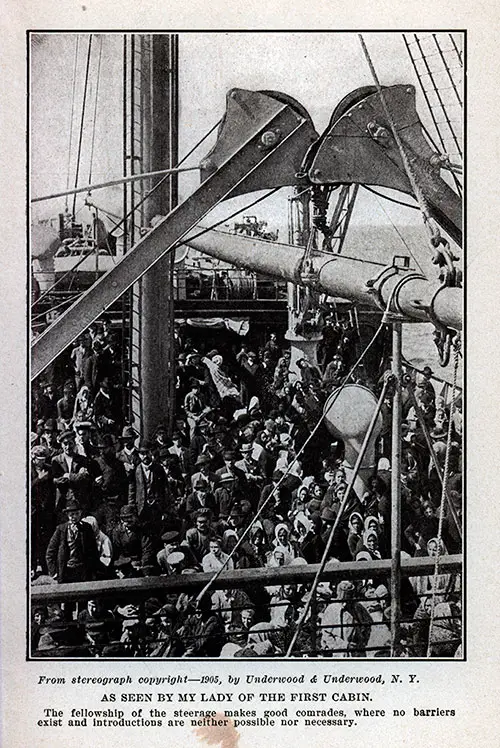

Steerage Passengers Crowded on Deck. From Stereograph by Underwood & Underwood, New York, 1905. GGA Image ID # 1d88074a41

Treatment of Women

There was an outside main deck and an upper deck on which steerage passengers were allowed. These were each about 40 feet wide by 50 feet long, but probably half of this space was occupied by machinery, ventilators, and other apparatus.

There was no canvas to keep out the rain, sun, and frequent showers of cinders from the smokestack. These fell so thick and fast that two young sailor boys were kept busy sweeping them off the decks. It is impossible to remain in one’s berth at the time, and as there were no smoking and sitting rooms, we spent most of the day on these decks.

No benches nor chairs were provided, so we sat wherever we could find a place on the machinery, exposed to the sun, fog, rain, and cinders. These not only filled our hair but also flew into our eyes, often causing considerable pain.

These same two outdoor decks were also used by the crew during their leisure. Then asked what right they had there, they answered: "As much as the passengers."

No notices hung anywhere about to refute this. How the sailors, stewards, firemen, and others mingled with the women passengers was thoroughly revolting.

Their language and the topics of their conversation were vile. Their comments about the women, and made in their presence, were coarse. What was far worse and of frequent occurrence was their handling the women and girls. Some of the crew were always on deck, and took all manner of liberties with the women, in broad daylight as well as after dark.

Not one young woman in the steerage escaped an attack. The writer herself was no exception. A hard, unexpected blow in the offender’s face in the presence of a large crowd of men, an evident acquaintance with the stewardess, doctor, and other officers, general experience, and manner were all required to ward off further attacks.

Some few of the women, perhaps, did not find these attentions so disagreeable; some resisted them for a time, then weakened; some fought with all their physical strength, which naturally was powerless against a man’s.

Others were continually fleeing to escape. Two more refined and very determined Polish girls fought the men with pins and teeth, but even they weakened under this continued warfare and needed some moral support about the ninth day.

The atmosphere was one of general lawlessness and total disrespect for women. It naturally demoralized the women themselves after a time. There was no one to whom they might appeal. Besides, most of them did not know the official language on the steamer, nor were they experienced enough to know they were entitled to protection.

The interpreter, who could and should a friend of the immigrants, passed through the steerage but twice a day. He positively discouraged every approach. I purposely tried on several occasions to get advice and information from him, but always failed.

His usual answer was, "How in the d___ do I know?" The chief steerage steward by his own familiarity with the women made himself impossible as their protector.

Once when a man passenger was annoying two Lithuanian girls, I undertook to rescue them. The man poured forth a volley of oaths at me in English. Just then, the chief steward appeared, and to test him I made a complaint.

The offender denied having sworn at all, but I insisted that he had and that I understood. The steward then administered this reproof, "You leave them girls alone, or I fix you easy.’"

The main deck was hosed down every night at 10 when we were driven in. The upper deck was washed only about four times during the voyage. At 8 each evening, we were driven below.

This was to protect the women; one of the crew informed me. What protection they gained on the same dark and unsupervised deck below isn’t at all clear. What worse things could have occurred them there than those to which they were already exposed at the hands of both the crew and the men passengers would have been criminal offenses.

Neither of these decks was lighted, because, as one sailor explained, maritime usage does not sanction lights either in the bow or stern of a vessel, the two parts always use by the steerage. The descriptions that I might give of the mingling of the crew and passengers on these outdoor decks would be endless and all necessarily much the same.

A series of snapshots would provide a more accurate and impressive account of this evil than can words. I would here suggest that any agent making a similar investigation be supplied with a Kodak for this purpose.

A Summary of the Investigators' Experience

To sum up, let me make some general statements that will give an idea of the awfulness of steerage conditions on the steamer in question. During these twelve days in the steerage, I lived in disorder and in surroundings that offended every sense. Only the fresh breeze from the sea overcame the sickening odors.

The vile language of the men, the screams of the women defending themselves, the crying of children, wretched because of their surroundings, and practically every sound that reached the ear, irritated beyond endurance.

There was no sight before which the eye did not prefer to close. Everything was dirty, sticky, and disagreeable to the touch. Every impression was offensive.

Worse than this was the general air of immorality. For fifteen hours each day, I witnessed all around me this improper, indecent, and forced mingling of men and women who were total strangers and often did not understand one word of the same language. People cannot live in such surroundings and not be influenced."

All that has been said of the mingling of the crew with the women of the steerage is also true of the association of the men steerage passengers with the women. Several times, when the sight of what was occurring about me was no longer endurable, I interfered and asked the men if they knew they might be deported and their actions reported on landing.

Most of them had been in America before, and the answer generally provided was "Immorality is permitted in America if it is anywhere. Everyone can do as he chooses; no one investigates his mode of life, and no account is made or kept of his doings."

Note a: “A small record book showing past employment, common among working classes in many sections of Europe. The “workbook" also serves as a local passport. (Resume from Note A)

A Typical New Type Steerage: An Investigator's Report

Report by the same investigator as to another vessel. Clearly, the experience was dramatically improved over the previous voyage. The text was edited for spelling, grammar, and clarity to improve readability.

The steerage, or third-class passage, as experienced on the steamer _______of the ______ Line, differed but slightly from the usual cabin passage, except in plainness and simplicity of appointment.

The steerage passenger was treated with every consideration from the very beginning of his relations with the line. It was not necessary that he be at the port of embarkation any significant length of time before the departure of the steamer.

I, for instance, arrived in London the day previous to the vessel’s sailing, presented myself at the company’s offices, requested passage, received my ticket immediately, and was told there was no necessity of leaving London until midnight.

This train brought many other emigrants and me to ____ in the morning of the day of sailing. Another train carried us from the same station to the docks. From here, a bus belonging to the _____ Line conveyed passengers and hand baggage to the steamer without charge. It was about 10 am when we went on board.

We were all placed in one of the large dining rooms, and from there passed the doctor in single file. He examined the eyes of each one, and we proceeded to a portion of the open deck.

Then we marched again in single file to another portion of the deck, giving up the two parts of the steamer ticket as we went and receiving a doctor’s card—those who were still without it.

The last official approached in this procession assigned staterooms and berths. This was done both judiciously and with an evident desire to give satisfaction.

Friends and acquaintances were placed together. The various nationalities were quartered near together as much as possible. The few Jewish passengers were assigned staterooms distantly removed from all the others.

All these proceedings followed a careful plan and were kindly conducted so that no excessive crowding and rough handling resulted. The same consideration that was shown here continued throughout the ten days’ journey.

The steerage passengers on board, examined, and assigned to their quarters, the steamer pulled out of the dock and proceeded to the landing where cabin passengers were taken on.

The steerage on the ______ presented practically no novelty and interest due to unique and inhuman accommodations. The same human needs were recognized as in the case of cabin passengers, and every revision was made for these. The appointments, however, were plain and simple and entirely devoid of all nonessentials.

Relative to the main deck, the first wholly enclosed deck extended the entire length and breadth of the vessel, the sleeping quarters were located on the first and second decks below the main deck.

These two decks were divided into sections designated by letters of the alphabet. These could be, and in some cases were, shut off from one another by iron bulkheads.

A separate entrance or stairway led to each section. In no case did a hatchway open directly from the upper or spar deck into a sleeping compartment, admitting water and wind.

Each section or compartment with but two exceptions was subdivided into staterooms. These contained two and four berths each.

The partitions were of wood, painted white, and kept thoroughly clean. A current of air was admitted at the base and top of the barriers. The air we breathed on these two decks, both in the staterooms and hallways, was remarkably fresh.

Berths were arranged in two tiers, and in construction apparently differed in no way from those usually found in the second cabin. Each berth contained a straw-filled mattress and pillow. Both of them were covered with white slips, which, however, were not changed during the ten days.

For covering, a pair of heavy gray blankets were provided. These were of ample size and weight to be practically sufficient even on the coldest nights of the journey.

At the head of the berths was a drop-shelf that served either as a seat or table, as the occasion demanded. Each room was furnished with a mirror, and hooks to hold clothes were quite abundantly supplied.

A lever for turning on the electric light in the room and a bell for summoning steward or matron were within easy reach of both berths. There was plenty of space for hand baggage under the lower berths and also beyond the foot of the berths.

The floors everywhere were of plain white boards, and these were kept scrupulously clean. They were scrubbed every day by the stewards on their hands and knees, and were well dried, to avoid all unnecessary dampness.

At 9 o’clock each morning, all the passengers except those who were ill or indisposed were requested to vacate their rooms. The stewards then went through them all, giving each such attention as it needed-making beds and sweeping or scrubbing floors. At intervals in the hallways were placed cans to receive waste.

These were not frequent and convenient enough to be used by all in cases of seasickness, but they did afford a place for other waste. If a criticism might be offered on the staterooms, it could only be on the lack of cans to use in case of seasickness.

The stewards were untiring in cleaning up the results of the innumerable cases of illness resulting from the rough sea during the first few days. Many of them provided such cans as were available for this disposition.

Each section was in the distinct charge of a steward, who was held strictly responsible for all order in his section. A steward was always on duty in the hallways, both day and night, and lights burned all night in the passageways.

Men, women, and families were assigned each to separate sections. The capacity of steerage passengers is 2,200. Staterooms are provided for 1,600. The two sleeping sections or compartments previously excepted from the arrangement just described contained about 300 berths each.

When the steerage is full, these two rooms are used as sleeping quarters for men. The berths are constructed and supplied precisely like those in the staterooms.

There were numerous toilet rooms, usually containing five basins each, with a faucet of running water and five toilets. The basins were of the conventional shape and size and were supplied each with a stopper that could be applied to retain water in the basin or removed to allow its escape.

There was always an abundance of soap, and large roller towels were supplied frequently enough to ensure the presence of clean ones at all times.

The floors in these rooms were of tile. These were practically always in a fit condition for use. Only when an accident occurred, occasioned by a leak in some pipe, was the floor wet, and this was remedied as soon as discovered.

The toilet rooms were all located on the main deck and as much as possible immediately at the head of stairs leading up from the sleeping quarters.

In no instance was it necessary to cross the open deck to reach a toilet room, and in many cases, it was not even necessary to cross a passageway other than the one on which the stateroom opened.

Since there were less than 250 passengers in the steerage, not nearly all the steerage quarters were in use. However, enough toilet rooms were open to avoid all crowding.

The toilet and staterooms of the men were so completely separated from those of the women that there was no possibility of mistaking them or using them in common. The supervision in this respect was particularly strict; men were positively kept out of the women’s quarters.

There were four large dining rooms for the third class, two on the main deck and two on the deck below. Only the two on the main deck were needed on this trip, and even these were only about half full each.

The one was used by the men passengers, the other by the women and families. The two were side by side and were served from one pantry, located between the two.

Long tables were seating from ten to fourteen persons. At meals, these were covered with white cloths, and each place was set with a thoroughly good knife, fork, and spoon. Bread, salt, pepper, and mustard were arranged all along the center of the table. Soup and meat were served from the pantry.

Vegetables preserves, pickles, and sugar were placed at either end of the table in large dishes, and each passenger could serve himself. Each table was in charge of one steward, who laid the cover, served, and attended to the wants of those there seated.

The service and attention were real and all that could be asked. The food was of very fair quality and abundant. Absolutely everything served was such as might be eaten without hesitation b anyone.

The preserves served with each breakfast and the fresh fruits, apples, and oranges, given out several times at dinner were of exceptional quality and would have made endurable, meals of much poorer quality.

Coffee, tea, and hot water could be had by women and children at almost all hours of the day from the pantry.

A bar opening on the passageway near the entrance to the men’s dining room afforded stout, ginger ale, soda water, and smokers’ necessities. This received some patronage but was not particularly popular.

Although the set of notices everywhere posted forbade the sale of all provisions by any of the crew, there were some such indirect dealings. Some passengers appeared on deck continually with apples and oranges when these had not been given out at the table.

Others, who were ill, complained they could eat nothing but fruit and that that was not available. It proved that those who could speak English or give tips to the right persons were abundantly supplied with fruit.

Nothing, however, was openly offered for sale except at the bar. The total seating capacity in the dining rooms of the steerage on the ______ is about 1,100. However, even when the steerage is full, all passengers are served at the table, so I was told. In that case, there are two sittings for each meal.

The Hebrew steerage passengers were looked after by a Hebrew who is employed by the company as a cook and is at the same time appointed by Rabbi ______ as guardian of such passengers. This particular man told me that he is a pioneer in this work.

He was the first to receive such an appointment. He must see that all Jewish passengers are assigned sleeping quarters that are as comfortable and good as any; to see that kosher food is provided and to prepare it. He has done duty on most of the ships of the ______ Line.

On each, he has instituted this system of caring for the Hebrews and then has left it to be looked after by some successor. An interpreter who spoke English, Swedish, Norwegian, and some German was on board to serve when needed.

He was, however, not at all conscientious in the performance of any duties and evidently not very capable. His price for granting privileges, performing favors, and overlooking abuses was a mug of stout.

I know him to have openly asked one passenger for such a treat and, judging from the number of gifts he received and the reputation given him by others of the crew, he did not hesitate to solicit free drinks from everyone. He was generally present in the dining room during meals, though he did nothing.

To young women passengers, his manner could be most friendly and gracious. To others, he was positively rude. He made most disparaging remarks about a German who merely refused to buy favor with drinks. A matron or stewardess performed necessary services for the sick. She brought food to those who were unable to go to the dining room.

At the table, she gave out milk to the children and served bouillon to women and children during the forenoon. She went the rounds of the sick at least three times a day to inquire after their needs and was patient enough in waiting on them. She could be even more obliging when her palm was crossed with a coin.

Only one serious complaint about her was heard during the journey. A group of Jewish women who occupied staterooms at an extreme end of the second deck below the main deck were ill and unable to attend meals.