PWA and Industry - 1938

Front Cover, PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1512a8e80c

Introducing A Study

The construction of public works has long been a first line of defense against unemployment in periods of severe depression. In judging the effectiveness of any program of public works as a means for reemployment, several groups of workers must be considered.

First, there are tinmen who work on the job itself. They are the carpenters, bricklayers, stone masons, ditch diggers, cement finishers, and the host of other skilled, semiskilled, and unskilled men who work with them.

Men and Rock at Grand Coulee [1]. Sign in Background Reads "Safety Pays." PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1512c3e36f

Second, there are the men in the factories which provide the brick, cement, lumber, or steel to be used on the job. Back of them are the miners, the loggers, and others who supply the raw materials for the factories; and last, there are the men on transportation systems which carry the materials to the factory and, later, to the job.

Employment of these secondary groups of workers is just as important in any reemployment program as the employment of men on the site of construction. For many types of public works the materials-makers and transportation men are numerically more important than the men on the job.

Notwithstanding the recognized importance of materials-makers and transportation employees, it has been impossible, until recently, to measure with any accuracy the amount of indirect labor provided by public works projects in the United States.

When a new road or bridge or a new school building was proposed, everyone knew that cement and brick and steel and lumber would be needed, but no one knew how many men would be employed in factories to make these materials or on the railroads or steamship lines to ship them to market.

The importance of such information, now and in the future, to the Department of Labor in appraising a proposed program of public works from the standpoint of reemployment, and to the Federal agencies which are engaged in supervising and operating public works programs, can hardly be overemphasized.

For that reason, the bureau of Labor Statistics welcomed the opportunity provided by the program of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works in 1933, to begin the first comprehensive study of "behind-the-lines employment" on public works jobs.

Every contractor or Government employee in charge of a project was required by the Administrator of Public Works to keep payroll records which showed the number of men employed on each P. W. A. job, the number of hours they worked, and the amount of pay they earned.

Summaries of these records were sent each month to the Bureau of Labor Statistics to give a running record of direct employment at the site. Each contractor or builder also notified the Bureau of the amount and value of materials which he ordered.

This provided a record of the total value of materials used in relation to the cost of the job us a whole and to the size of the payroll. The Bureau then sent inquiries to the manufacturer of the materials to whom a contract had been let asking how many man-hours of labor would be required in the process of fabrication.

This gave a measure of the amount of labor required by the manufacturer or dealer who sold the materials, thus measuring the first stage of indirect employment.

Calculations: In Search of Labor Figures. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1512f0198b

This file of records has been maintained throughout the life of the public works program, for more than 4-years, and is being built up every day. The study has had the generous cooperation and assistance of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, and of the thousands of contractors and Government construction agents who have been in charge of actual construction jobs; of the makers of steel, of cement, of brick, and of the many other products used in the program.

Even these records did not tell the full story as to the amount of labor which had originally gone into the product before it reached the manufacturer who sold it to the P. W. A. contractor.

For steel, cement, lumber, brick, and plumbing and heating supplies the record was traced far back along the line to the original supplies of raw materials, to the railroads, into the factory for fabrication and again along transportation systems to the P. W. A. job. Mines, railroads. far lories, and shipping lines opened their records for the personal inspection of agents of the Bureau, so that these facts could be obtained.

In 1933 it was not possible to gage accurately what would happen us a result of an expenditure of a works fund of $3,300,000,000. With millions jobless and industry idle, the program had the general aim of putting to work as many men as possible, and reviving industry as widely as possible.

But no measured, specific, sharply defined objective, in terms of a definite number of people to lie aided in designated areas or particular sectors of business, was possible, for no factual basis existed with which to measure.

The studies of the Bureau of Labor Statistics have now segregated the benefits to industry and employment arising from each major type of public works construction. They show what happened to men and machines when waterworks and sewers were chosen as desirable public works.

They traced the orders which resulted when public buildings were erected, and when reclamation projects were undertaken. They measured direct and indirect labor created when railroad construction was authorized.

With the material from these surveys, it is possible to forecast with a reasonable degree of accuracy the results which might be expected from new works programs should they be deemed desirable.

It should be possible also to choose types of needed projects which could be undertaken to bring aid to a specified area of the country or to a particular branch of industry which may be suffering from lack of activity.

Thus, knowledge of how the erection of public buildings or of waterworks affects the building trades, the material and construction-supply companies in industry, provides more exact procedures for any new public works program than were available in 1933.

Public Works Program 1933-37

The need for employment in the construction industry and all of the industries which supply its materials was greatest in 1933, when the enlarged public works program of the Federal Government was set in motion by the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which President Roosevelt signed on June 16 of that year.

During the first half of 1933, virtually no new construction work had been done by private organizations. Although the Government had already increased its program of public building to some extent, the total volume of contracts for new construction in the first 6 months of 1933 was only 14 percent as large as in the corresponding period of 1929.

This extremely low volume of activity was the culmination of 5 years of drastic reductions in new construction. Contractors and builders, workers in the building trades, and employees normally at work in factories fabricating building materials were widely unemployed. Construction was more severely depressed than any other major American industry.

As an inevitable consequence, the heavy industries were also depressed. In the first half of 1933 factories making durable goods of all kinds employed only 44 percent as many men as in 1929, lumber mills had 45 jicrcent of their 1929 crews, cement mills 44 percent, and steel mills .51 percent. Many of these workers themselves were on short time.

The original act which established the Public Works Administration provided a total fund of $3,300,000,000 to be allotted for various kinds of public works and public relief projects.

Later acts enlarged the funds and extended the life of the organization through June 1939. Since June 1937, P. W. A. has had no new funds, but has financed certain previously approved types of projects using its remaining unexpended funds and proceeds from the sale of securities.

The Public Works Program which began in 1933 was undertaken in three major divisions: Projects to be conducted directly by agencies of the Federal Government, projects to be undertaken by State, and local authorities or other non-Federal bodies, and loans to industry on a commercial basis for such purposes as the development and improvement of the railroads or other private construction activities.

State and local authorities which operated under the program provided most of the funds for their projects, but P. W. A. was authorized initially to make direct grants from the Federal Treasury amounting to 30 percent of the cost of labor and materials to be used on the projects.

Later the maximum grant was raised to 45 percent of total cost. The State or local agency financed the remaining 70 or 55 percent. In some cases, P. W. A. provided necessary funds for local projects in the form of loans.

All public works projects, in order to be approved, were required to have specific social value and to be conducted in such a way as to relieve unemployment in areas where the local employment situation had become serious.

Rules governing the work provided for the payment of prevailing wages in the locality and for the protection of pay envelopes against "kick-backs". Most of the hiring was done either through trade- unions, where contractors had an agreement with a union, or through the offices of the United States Employment Service.

To assure the widest possible use of the appropriations for financing public works. P. W. A. required that every project be economically planned and constructed.

Most of the work on these public works projects, with the exception of some Federal projects, was done by contracts awarded to private contractors. All work was under the general supervision of P. W. A. engineers and inspectors.

From its beginning in July 1933 to the end of 1937, the Public Works Administration financed the construction of nearly 16,000 Federal public works projects and 10,500 public works for State, local, and commercial agencies.

The value of contracts awarded for construction in the shorter period from July 1933 to June 1937, covered by the special study of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, totaled nearly $3,700,000,000, a substantial share of which was provided by State and local agencies.

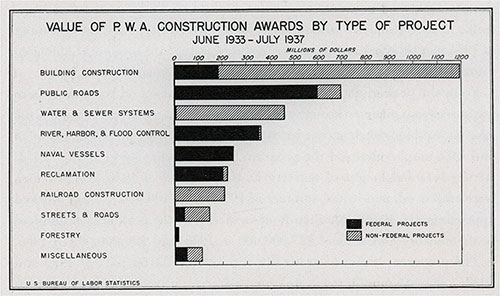

Graph of the Value of P.W.A. Construction Awards by Type of Product, June 1933 - July 1937. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 151334d218

Many different kinds of public works were undertaken under the program. The most popular type was public buildings, constructed by State and local authorities.

They built schoolhouses, courthouses, city halls, hospitals, and many other needed public buildings, valued at more than $1,200,000,000.

Road work undertaken by the Federal Bureau of Public Roads and other Federal agencies cost nearly $700,000,000, and water and sewerage systems for local use over $450,000,000.

Federal army engineers and other Federal agencies spent $360,000,000 on flood control along the Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and other rivers, and in deepening river channels and harbors.

The value of different kinds of public works projects undertaken by Federal and non-Federal agencies is shown in the accompanying chart. These are the projects for which men and materials were required.

The program got under way in 1933, first on road work for which project plans were already completed, and later on the larger and more complex engineering jobs which required a longer time to plan, such as reclamation projects, sewerage and water systems, and local public buildings.

By the spring of 1934, the program was expanding rapidly and in August 1934 activity reached its peak. At that time, according to the records of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 630,000 men engaged on P. W. A. projects.

In this one peak month of August 1934, there were more than 60,000,000 man-hours worked at the site on these construction projects. Payrolls went up with corresponding rapidity. In the beginning of 1934, monthly pay envelopes for workers at the site totaled $12,800,000 a month and at the height of the program in August $35,300.000.

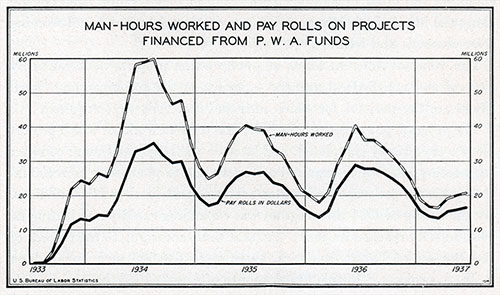

From the peak of activity in August 1931, as shown on the chart, there was a seasonal decline throughout the autumn and winter as is always the case on outdoor construction where had weather slows up work. In 1935 and 1936, employment on the program was somewhat lower than in 1934.

At the seasonal height of activity in the summer of 1935, 450,000 men were employed, and in the summer of 1936 about 400,000. They worked approximately 40,000,000 man-hours a month at the peak season and had peak monthly payrolls of $27,000,000 in 1935 and $29,000,000 in 1936.

The program slackened gradually through the latter part of 1936 and 1937. Private employment was increasing rapidly in the heavy manufacturing industries, and in certain types of private construction.

The Federal Government also undertook other types of projects for the relief of unemployed but employable workers. The month-by-month record of man-hours of labor and monthly payrolls on the P. W. A. program from July 1933 through June 1937 is shown on the chart. All of the detailed figures are given in table 4 of the appendix to this bulletin.

Man-Hours Worked and Payrolls on Projects Financed from P.W.A. Funds, 1933-1937. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 151371dabd

Throughout the 4-year period to the end of June 1937, 1,423,000,000 man-hours of direct labor were worked on job sites. Of this total 867,000,000 were put in on Federal jobs and 556,000,000 on non-Federal work.

Payrolls for men on the job totaled $960,000,000 for the entire program. Five hundred thirty-four million dollars of this went into pay envelopes on federal projects and over $426,000,000 on non-Federal projects.

This measures only the Work on the job—the employment given to bricklayers, stone masons, carpenters, plumbers, truck drivers, cement finishers, day laborers on the roads, and many other skills which the public works program called into action.

P.W.A. Orders Mean Steel Mill Employment. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1513937944

The creation of payrolls because of this direct employment had obvious secondary benefits. Workers previously without jobs can devote pay checks to the purchase of necessities hitherto denied their families.

New clothing is purchased, furniture and household equipment bought., medical rare previously postponed is obtained. Families can enjoy a more ample board, buying power is put into action.

This has a direct effect on merchants who sell to the reemployed workers. If their business improves measurably, they are enabled to put on additional help.

As their shelves are cleared of old stocks, new goods must he supplied. Here consumers' goods industries enter the picture. With renewed orders, they may have to augment their employment, hehl down during lean years. An enlarged demand for raw materials is felt.

It is obviously impossible to calculate the entire effects of the stimulus given by employment created on a project. However, secondary benefits do exist, and they add their force toward general economic stimulation.

Factory Wheels Turn

As plans were completed and ground broken for projects, orders went forward to factories from the contractors, for machinery to do the work and for materials for the job.

Factories railed men hark to work and, in their turn, ordered raw materials or partly fabricated supplies which they needed from mines, quarries, cotton warehouses, lumber camps, and steel mills.

Rail, truck, and water traffic increased as these materials moved to factories, and finished steel, plumbing, or cement moved to the jobs on which they were to be used.

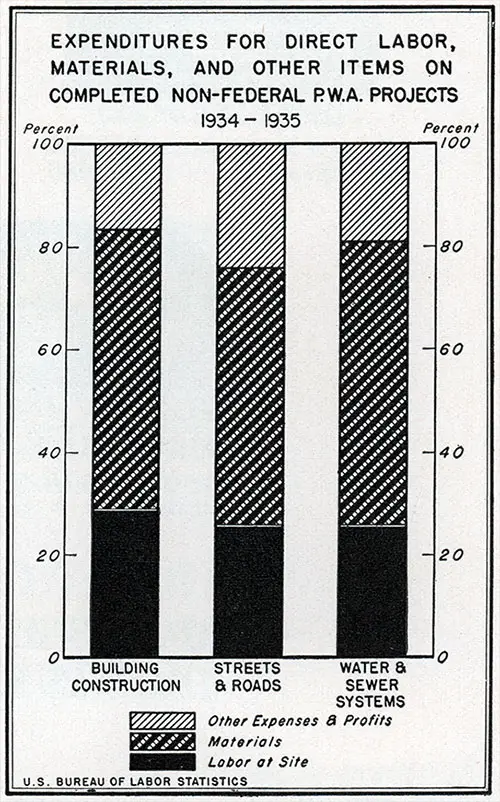

In almost all kinds of public works the cost of materials exceeded the amount of money paid out in wages to the skilled and unskilled men engaged in construction at the site.

Expenditures for Direct Labor, Materials, and Other Items on Completed Non-Federal P.W.A. Projects, 1934-1935. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The chart shows the relative cost, of labor at the site and the value of orders for materials for each of the principal types of public works undertaken by the program. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 15139d295c

On non-Federal building construction jobs labor at the site received 28 percent of the total outlay, materials 55 percent, and other expenses and profit 17 percent.

On street and road project undertaken by localities, 26 percent went to site labor, 50 percent to materials, and 24 percent for other expenses and profits. Water and sewerage projects also expended about 26 percent for labor, 55 percent for materials, and 19 percent for other expenses.

Highest material cost of all was on railroad shop work, where 75 percent of the funds were expended for parts and materials to build and repair cars and locomotives, and 25 percent for direct labor.

Forestry projects alone paid out more for the salaries of men engaged directly on projects than for materials. This work consists largely of clearing land and making trails and camp sites, and requires comparatively few supplies.

Orders placed for materials on P. W. A. projects totaled more than $1,700,000,000 in 4 years from July 1933 to June 1937. These orders went to practically every line of industry in the country.

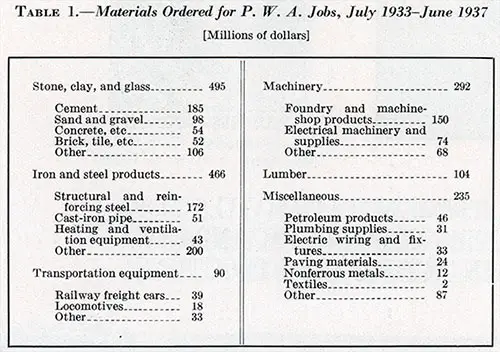

Table 1: Materials Ordered for P.W.A. Jobs, July 1933 - June 1937 (in Millions of Dollars). The table shows the kind of materials P. W. A. dollars bought. Cement and steel, foundry and machine-shop products, and products of lumber lead the list. For some heavy industries, these orders were strong contributing factors for stability in the early years of the program before private industry again began to use heavy materials. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 15139f2ce3

Cement orders from P. W. A. took 72 percent of the entire domestic cement output in 1934. As general business revived, these orders became relatively less important, although in 1935 they accounted for 37 percent of the total. By 1936 they had dropped to 17 percent of domestic output.

P. W. A. orders for brick and hollow building tile increased each year from 1934 to 1936. In 1934, they amounted to about one-fourth of the estimated value of all shipments, in 1935 to 27 percent, and in 1936 to 43 percent.

Steel rail mills benefited almost as much as cement and brick. In 1934, the railroads which were granted P. W. A. loans to make repairs to their roadbeds or to extend their lines, placed orders accounting for 48 percent of the value of all rails produced in that year.

These orders tapered off considerably during the next 2 years. In 1935, they amounted to 9 percent of the value of the Nation's purchases and in 1936 to 6 percent.

In the lumber industry, P. W . A. orders in the 3 1/2 years from July 1933 through December 1936 totaled 3,375,000,000 board feet.

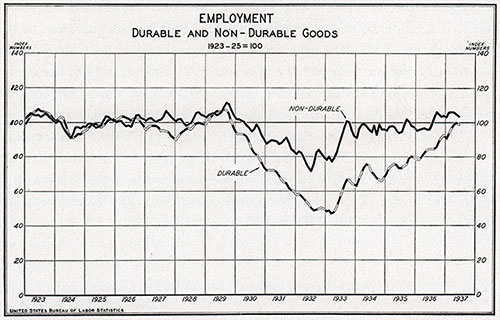

Many of the other heavy industries, severely depressed in 1933 and 1934, were given an initial impetus in 1934 and 1935 from P. W. A. buying. They continued to provide materials for the Public Works Program in 1936 and 1937.

Employment: Durable and Non-Durable Goods, 1923-1937. (1923-25 = 1000). United States Department of Labor Statistics. During all of this period of employment in the heavy industries recovered rapidly, as is indicated on the chart. It is clear that in some industries, P. W. A. orders played a vital part in increasing employment. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1513af787a

The amount of employment actually given to factory labor as a result of these orders for materials was shown by monthly reports submitted by nearly 40,000 contractors who placed hundreds of thousands of contracts, and by the factories from which the materials were ordered.

In five of the major industries which supplied the principal materials for public works, the Bureau of Labor Statistics made intensive studies of the accounts kept by individual companies to determine us precisely as possible the amount of labor generated all along the line from the mine that supplied the ore, or the logging camp in which the original trees were felled to make the lumber, through the transportation system to the factory.

These products were steel, cement, lumber, brick and other clay products, and plumbing supplies. Transportation agencies were also studied in detail.

These analyses indicated that for every hour of labor created on a public works project undertaken by a non-Federal agency, 2.5 hours were spent by employees engaged in supplying and transporting the materials for the project.

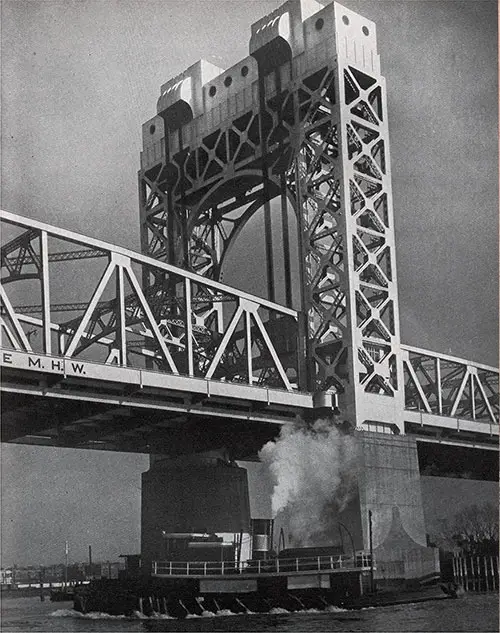

Socially Useful Projects Serving a Definite Purpose such as this Vertical Lift Bridge. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 151442920b

On this basis, it is estimated that more than 1,400,000,000 man-hours of labor were required in mines, forests, factories and on transportation systems to supply the necessary materials and take them to non-Federal P. W. A. jobs, and in administration.

When this is combined with the 550,000,000 man-hours of direct employment at the site, it appears that the non-Federal P. W. A. construction program as a whole created 1,956,000,000 man-hours of work.

This is the equivalent of the employment of 980,000 men for one year, assuming that 2.000 hours represent a normal year of full employment. Analysis has not been completed of projects on the Federal program, which in the aggregate provided more labor at the site than the non-Federal program.

There was considerable difference in the amount of indirect labor needed to supply materials for different types of projects. For example, construction of water supply systems involved much less indirect labor than light and power plants, which require expensive heavy machinery, and forestry projects required least of all.

For Future Use

With a look to the future, the Bureau of Labor Statistics singled out for special study three types of projects which figured heavily in the P. W. A. program from 1933 through 1937—public buildings, water and sewerage projects, and reclamation projects.

On the basis of experience with hundreds of millions of dollars worth of construction, the Bureau developed fundamental ratios for determining the industrial and employment benefits which would result from an expenditure of $1,000.000 on each type of project.

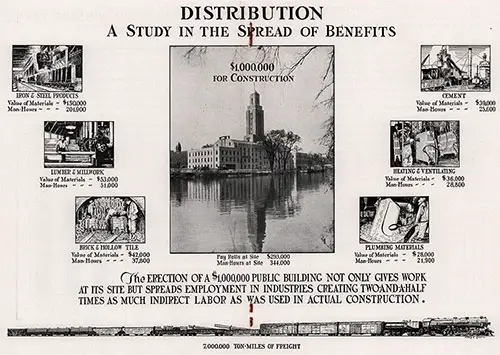

The indirect labor created by every $1,000,000 of contracts awarded for public buildings is illustrated below:

Distribution: A Study in the Spread of Benefits. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1513cecedb

Distribution: A Study in the Spread of Benefits. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1513cecedb

DISTRIBUTION - A Study in the SPREAD OF BENEFITS

THE ERECTION OF A $1,000,000 PUBLIC BUILDING NOT ONLY GIVES WORK AT ITS SITE BUT SPREADS EMPLOYMENT IN INDUSTRIES CREATING TWO AND A HALF TIMES AS MUCH INDIRECT LABOR AS WAS USED IN ACTUAL CONSTRUCTION .

$1,000,000 for Construction

Payrolls at Site: $293,000

Man-Hours at Site:344,000

IRON & STEEL PRODUCTS

Value of Materials: $150,000

Man-Hours: 201,900

LUMBER & MILLWORK

Value of Materials: $53,000

Man-Hours: 51,000

BRICK & HOLLOW TILE

Value of Materials: $42,000

Man-Hours: 37,800

CEMENT

Value of Materials: $39,000

Man-Hours: 25,600

HEATING & VENTILATING

Value of Materials: $36,000

Man-Hours: 28,800

PLUMBING MATERIALS

Value of Materials: $28,000

Man-Hours: 21,900

7,000,000 TON-MILES OF FREIGHT

About 344,000 man-hours of labor would be created at the site. For the mining and production of raw materials, transportation, manufacture, and distribution necessary to supply the needs of the $1,000,000 contract, 710,000 man-hours of indirect or "behind-the-lines" labor would be required.

Thus, for the expenditure of $1,000,000 on a public building, a total of 1,084,000 man-hours of employment would be created. Of the total, only a portion would appear directly at the site, the balance being spread through manufacturing, transportation, and production of raw materials, and in administration and overhead on the project, as shown in the chart. Thus, the expanding wave of employment would move out to many points of the industrial system.

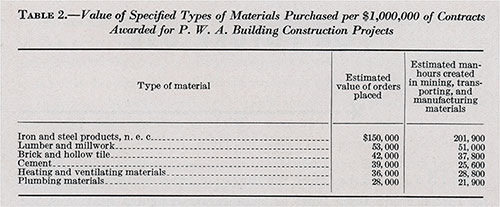

Six major types of building materials were found to benefit chiefly from the construction of public buildings. If a $1,000,000 contract were to be awarded for a public building under the same conditions as those which prevailed during the height of the P. W. A. program, the approximate volume of orders indicated in table 2 might be expected for these six types of materials. Man-hours of employment required to make these materials are also shown.

Table 2: Value of Specified Types of Materials Purchased per $1,000000 of Contracts Awarded for P.W.A. Building Construction Products. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1514072bb3

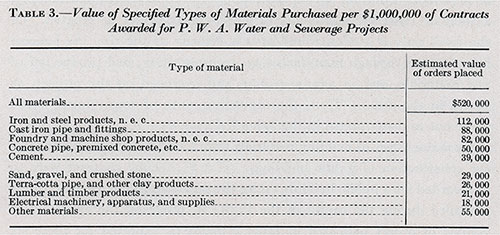

On water and sewerage projects a somewhat larger volume of direct on-site employment may be expected. For $1,000,000 of contracts awarded, it is estimated that 387,000 man-hours of site employment would result.

To supply the materials for the projects would require 760,000 man-hours behind the lines in the mines, forests, mills, factories, distribution yards, on the railroads and truck lines handling transportation, and other expenses on the project.

For a $1,000,000 award in contracts for water and sewerage projects, therefore, a total of about 1,147,000 man-hours of direct and indirect labor would be. anticipated.

A wide variety of materials is required for projects of this type. The orders to be expected by industry from this kind of undertaking are shown in table 3.

Table 3: Value of Specified Types of Materials Purchased per $1,000,000 of Contracts Awarded for P.W.A. Water and Sewage Projects. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 15141fd1f5

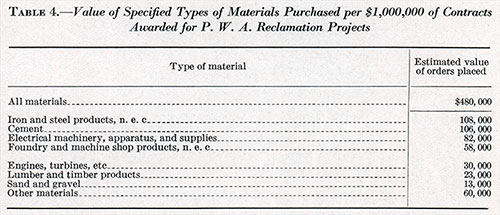

Reclamation developments were next analyzed for their future possibilities. In this ease it was found that for every $1,000,000 of contracts, 402,000 man-hours of direct employment would he created.

This would mean in turn that close to 691,000 man-hours would be required in ''unseen" employment to supply the needs of the men on the line. An idea of the type of materials necessary is provided by table 4, showing the amounts of each kind of material necessary for every $1,000,000 of contracts awarded.

Table 4: Value of Specified Types of Materials Purchased per $1,000,000 of Contracts Awarded for P.W.A. Reclamation Projects. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1514929d54

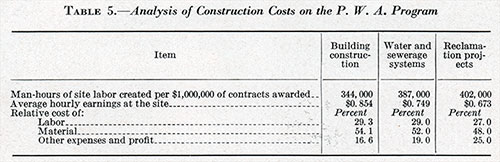

A cross-section of the expenditures of public works funds on these three types of programs is given in the analysis of construction costs on the P. W . A. program in table 5.

Table 5: Analysis of Construction Costs on the P.W.A. Program. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1514a105da

Analysis of cost on more than one thousand completed non-Federal P. W. A. projects indicates that the equivalent of the employment of one man for 1 month in labor at the site and on materials can be provided by the expenditure of approximately $136.

Of this amount, about $61 or 45 percent was provided by the Federal Government during the latter part of the P. W. A. program, and $75 was paid by the community which undertook the project.

This composite man-month of labor would be worked at the construction site or in a mine, forest or factory, in the transportation and distribution of materials, or in the administration of the project. In making this estimate, the Bureau based its figures on wages and working conditions prevailing in 1937 in the construction industry and in other industrial enterprises.

Thus, the estimate is up-to- date with reference to wage levels and other costs, although much of the information on which the study is based was obtained from P. W. A. projects begun in 1934 and 1935.

Thus, through measurement of the results of the public works program in actual operation, yardsticks have been evolved by which the effects of future programs can be evaluated in advance.

Should a new public works program be undertaken at some future time, the facts provided by this study will enable those who are planning it to appraise proposed projects with a view to providing the wisest distribution of employment and the most effective use of labor.

Machinery Used on a P.W.A. Project at Rest. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1514c776e7

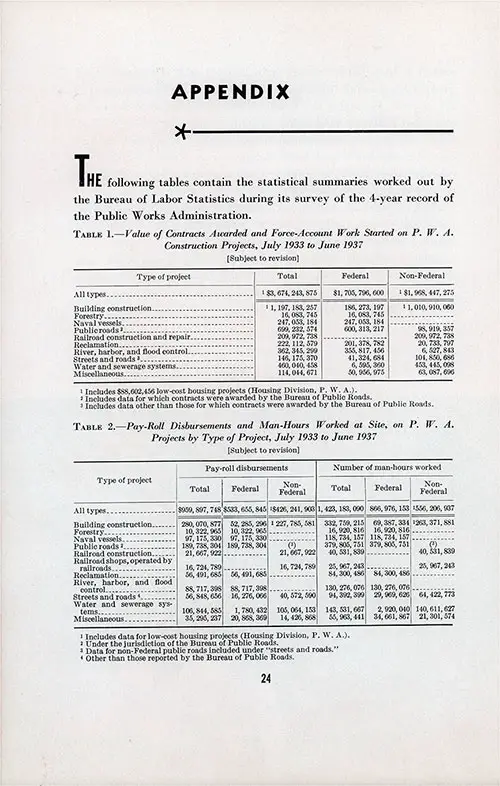

Appendix

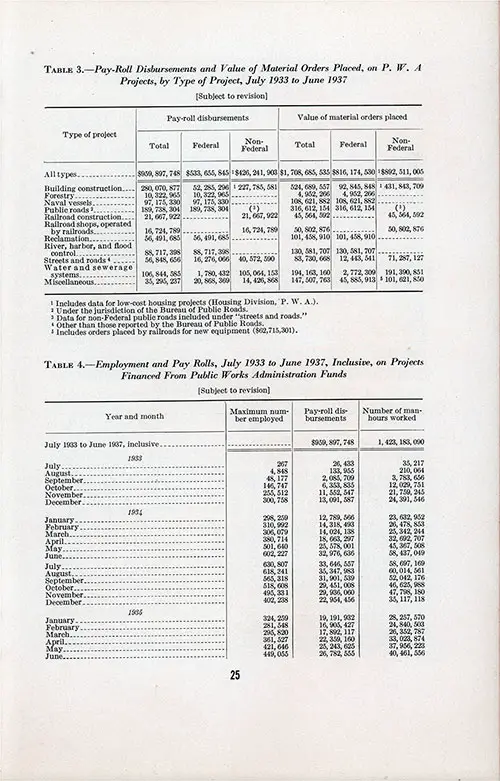

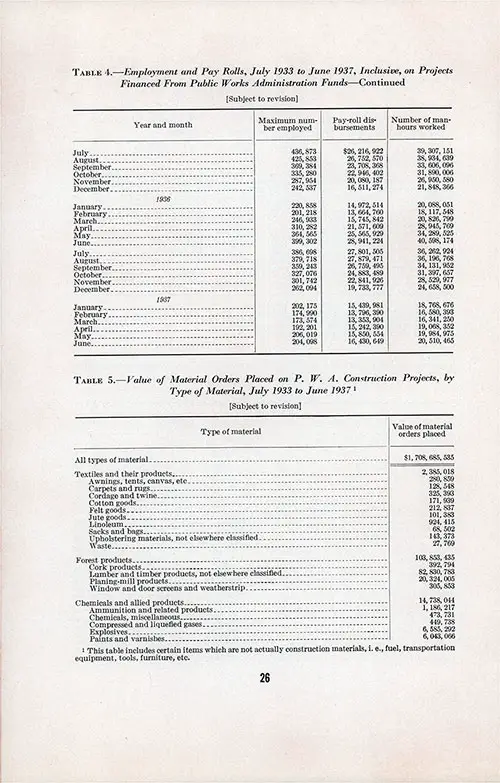

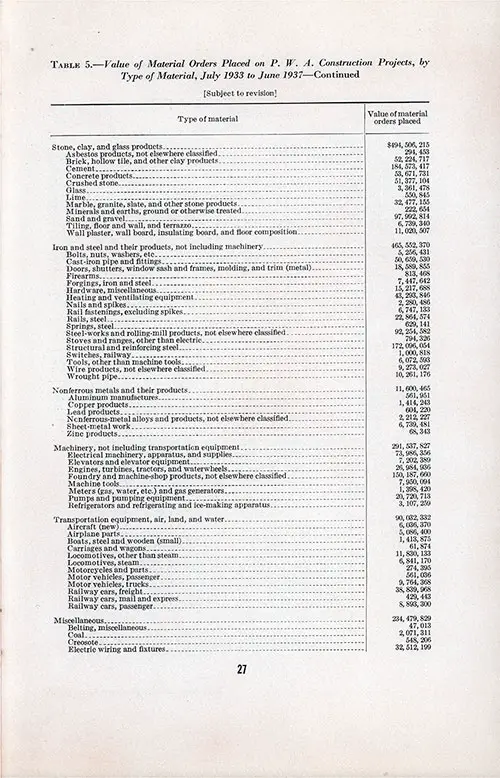

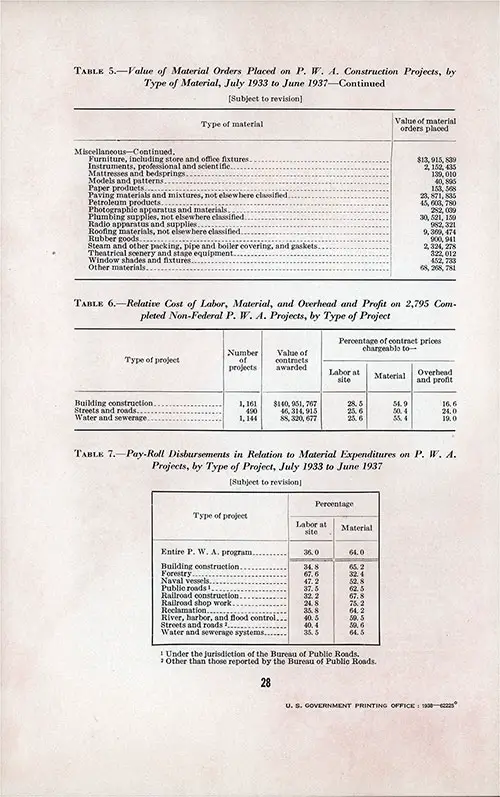

The following tables contain the statistical summaries worked out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics during its survey of the 4-Year record of the Public Works Administration.

Note: The Appendix is reproduced here in image format only for use by students and teachers studying the Great Depression.

Appendix Page 24. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1515025362

Appendix Page 25. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1515540d6e

Appendix Page 26. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 15155c0fc5

Appendix Page 27. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1515c1b747

Appendix Page 28. PWA and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employement, Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1515d5fa62

End Notes

Note 1: Grand Coulee Dam is a concrete gravity dam on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington, built to produce hydroelectric power and provide irrigation water. Constructed between 1933 and 1942,

Bureau of Statistics, United States Department of Labor, "P. W. A. and Industry: A Four-Year Study of Regenerative Employment," Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents, Bulletin No. 658, 1938. Isador Lubin, Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics; Frances Perkins, Secretary of the United States Department of Labor.