Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation - WPA - 1937

Front Cover, Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1536504cbe

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL

Works Progress Administration,

Washington, D. C.,

June 15, 1937.

Sir: I have the honor to transmit an analysis of the social and economic characteristics of farm operators and farm laborers receiving assistance under the general relief and rural rehabilitation programs. The analysis contributes significant material on the incidence of relief in the various agricultural groups and thus provides necessary information for the determination of future policies for the relief of unemployment in rural areas. The report is based on data obtained through surveys of Current Changes in the Rural Relief Population, conducted by the Division of Research, Statistics, and Finance of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

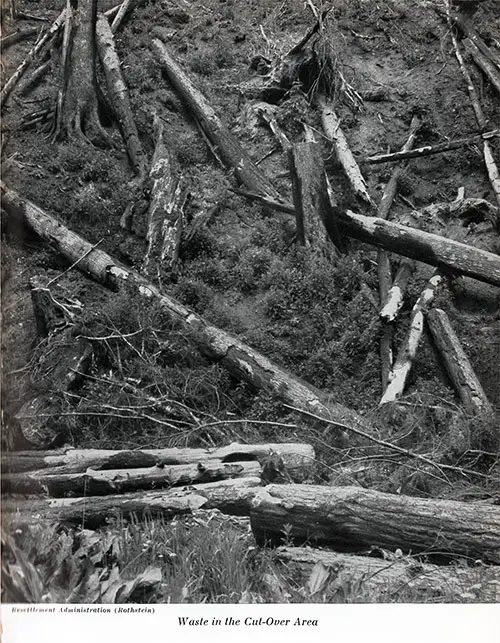

The report emphasizes the fact that the depression in agriculture began long before 1929 and that the distress of the early 1930's merely accentuated farm problems of long standing. Chief among these problems are: the pressure of rural birth rates on farm opportunities; the attempt to farm lands which are sub-marginal in production or approaching sub-marginality; attempts to farm eroded lands and adoption of farming practices which are conducive to erosion; subdivision of farms into units too small to afford support for a family; concentration on commercial rather than subsistence farming; overcapitalization of farms and consequent heavy foreclosures; decline of certain extractive industries, especially lumbering and mining, with consequent loss of the supplementary income which many farmers depended on for an adequate budget; growth of the tenant system; and increase in low-paid wage workers in agriculture. The situation has become acute in recent years, due largely to the lack of parity of prices of farm products and to the cumulative influence of a succession of disastrous droughts. The extension of relief into rural areas has focused attention on the human needs of the low-income farm families.

The study was made in the Division of Social Research, under the direction of Howard B. Myers, Director of the Division. The data were collected under the supervision of A. R. Mangus and T. C. McCormick, with the assistance of J. E. Hulett, Jr., and Wayne Daugherty. Acknowledgment is also made of the cooperation of the State Supervisors and Assistant State Supervisors of Rural Research who were in direct charge of the field work. The analysis of the data was made under the supervision of T. J. Woofter, Jr.r Coordinator of Rural Research.

The report was prepared by Berta Asch, whose services were made available to the Works Progress Administration by the Resettlement Administration, and by A. R. Mangus; it was edited by Ellen Winston and Rebecca Farnham. Special acknowledgement is made of the contribution of T. J. Woofter, Jr., who wrote the Introduction and Chapters I, VI, and VIII. A. R. Mangus contributed Chapter VII and Appendix B—The Methodology of Rural Relief Studies.

Respectfully submitted.

Corrington Gill,

Assistant Administrator.

Hon. Harry L. Hopkins,

Works Progress Administrator.

INTRODUCTION

This study was undertaken to assemble information concerning the relief and rehabilitation needs of farmers and to clarify the problems of the farm families that became dependent on public assistance during the depression.

The specific objectives have been to describe the extent of the farm relief problem and the underlying causes of distress; the development of the administrative programs which were formulated to meet the situation; the types and amounts of assistance given farm households; the social characteristics of these households; the relation of farmers on relief to the land with respect to residence and tenure and their relation to the factors of production and experience; and the trend of farm relief through 1935.

The sections describing the social and economic characteristics of relief and rehabilitation clients are based mainly on an analysis of farm households receiving aid in June 1935. This month was selected because it was considered less subject to seasonal and administrative fluctuations than other months for which similar data are available.

Supplementary data, however, are drawn from relief studies that were made in February 1935 and October 1935 in the same sample areas as was the June study. Material is also drawn from previous Works Progress Administration studies, principally Six Rural Problem Areas, Relief-Resources-Rehabilitation and Comparative Study of Rural Relief and Non-Relief Households.[Note 1]

In chapter VII, "Relief Trends, 1933 Through 1935," use is made of reports of the Resettlement Administration and of the Works Progress Administration, and of the study made by the latter organization of cases opened and closed by relief offices between March and October 1935.

The data presented in this report were obtained by means of a sample enumeration.[Note 2] The June relief study included 116,972 rural cases, in 300 counties representing 30 States, of which 37,854 were those of farm operators; 58,516 of the total rural cases were in 138 counties representing 9 agricultural areas. Of these, 18,126 were farm operator households. The estimated United States and State totals were based on the larger sample.

The sample counties were systematically chosen as representative of varied types of agriculture in the States and areas surveyed. These counties contained 12.1 percent of all the farm operators in the States sampled [Note 3] and 8.1 percent of farm operators in the areas sampled. The information on the schedules was obtained from case records in the county relief offices.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

This study is concerned with heads of families, either farm operators or farm laborers, 16 to 64 years of age. Those 65 years of age and over are arbitrarily excluded since they are considered as having passed their productive period.

Farm operators include both farmers still remaining on their land and those forced to leave their farms [Note 4] but whose usual occupation had been farming. In all areas, the study separates farm operators into two groups, owners, and tenants, while in the Cotton Areas, a third group, sharecroppers, as distinguished from other tenants, is represented.

Farm owners are farmers who own all or part of the land which they operate. Farm, tenants are defined as operating hired land only, furnishing all or part of the working equipment and stock, whether they pay cash, or a share of the crop, or both, as rent.

Fallen Trees Lay Waste in the Cut-Over Area. Photo by the Resettlement Administration (Rothstein). Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1536bb0e3a

Croppers are tenants to whom the landlord furnishes all the work animals, who contribute only their labor, and who receive in return a share of the crop. Farm laborers are persons who work on a farm with or without wages under the supervision of the farm operator. [Note 5] The major part of the discussion of laborers is confined to heads of families.

For purposes of this survey, a person was regarded as having had a usual occupation if at any time during the last 10 years he had worked at any job, other than work relief, for a period of at least 4 consecutive weeks.

If the person had worked at two or more occupations, the one at which he had worked the greatest length of time was considered the usual occupation. If he had worked for an equal length of time at two or more occupations, the one at which he worked last was considered the usual occupation.

A person on relief continuously from February to June was defined as currently employed in June if he had had non-relief employment lasting 1 week or more during February, the month of the preceding survey.[Note 6]

For cases opened or reopened from March to June, a person was considered currently employed in June if he had had non-relief employment, including employment as farm operator or laborer, during the week in which the first order for relief was received. The type of current employment is referred to hereafter as current occupation.

AGRICULTURAL AREAS SURVEYED

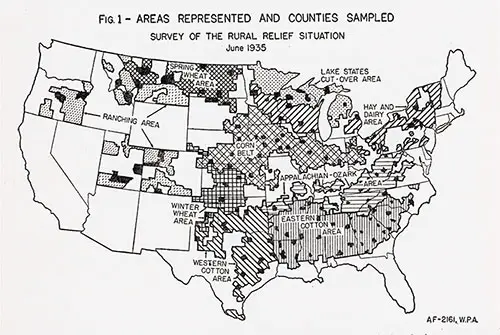

Although relief and rehabilitation rates are given by States, this study is primarily based on data for nine major agricultural areas. They are: the Eastern Cotton Belt, which includes portions of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas; the Lake States Cut-Over Area in northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan; the Western Cotton Area, including parts of Oklahoma and Texas; the Appalachian-Ozark Area, including the mountainous sections of West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas; the Spring Wheat Area in the northern part of the Great Plains; the Winter Wheat Area in the southern part of the Great Plains; the Ranching Area scattered through the mountain States; the Hay and Dairy Area, which stretches from New York along the Great Lakes to Wisconsin and Minnesota; and the Corn Belt in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri.

Fig. 1: Areas Represented and Counties Sampled. Survey of the Rural Relief Situation, June 1935. AF-2161, WPA. Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 15364eb77c

Figure 1 delineates these areas and indicates the counties sampled as representative of conditions in each area. The first six regions constitute definite rural problem areas. [Note 7] The Ranching Area may also be listed as a problem area, insofar as it has been affected by recent droughts.

The Hay and Dairy Area and the Corn Belt are more nearly normal agricultural regions and as such are especially interesting for a study of the general farm relief problem. This is particularly true of the Corn Belt, which was especially benefited by the corn-hog program of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration.

SUMMARY

The farm families that have received public assistance under the various Federal relief programs were only in part victims of the depression. In many cases, the need for outside aid was the result of long-standing agricultural maladjustments and adverse climatic conditions such as drought and flood.

A large majority of the farmers and farm laborers receiving public assistance, up to the summer of 1935, were clients of the general relief and rural rehabilitation programs of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. During the last half of 1935, the Federal Works Program and the Resettlement Administration took over the bulk of the load.

LOCATION OF FARM RELIEF AND REHABILITATION CASES

Over a million farmer and farm laborer families in rural and urban areas were on relief and rehabilitation rolls in February 1935, and almost 600,000 farmers in rural areas received relief grants or rehabilitation advances under the Federal programs in June 1935.

The June farm relief load varied widely among the States. New Mexico, with more than one-third of its fanners receiving these types of Federal aid, was followed in order by the Dakotas, Oklahoma, and Colorado, with more than one-fifth of all farmers on relief or rehabilitation, and by Kentucky, Florida, Idaho, Montana, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Arkansas, South Carolina, and Wyoming, each with 10 percent or more of their farm families receiving such aid. In the country as a whole, the proportion of all farm families receiving relief grants or rehabilitation advances in June averaged 9 percent.

The 14 States in which the relief load was concentrated contained only one-fourth of all farms in the United States in 1935; yet they contained over one-half of all farmers receiving relief grants or rehabilitation advances in June of that year.

The concentration of relief in these States primarily reflects the effects of the 1934 drought and the long-standing ills of the Appalachian-Ozark Area with its poor soil and abandoned industries.

Entrance to an Abandoned Coal Mine. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Jung). Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1537841852

At the same time, the heavy relief loads in these States, as compared with others suffering from similar unfavorable conditions, reflect differences in relief policies, more liberal in some sections than in others.

TYPES AND AMOUNTS OF RELIEF AND REHABILITATION

Types and amounts of relief grants and rehabilitation advances to farm families in June 1935 differed widely among various agricultural areas. Since the administration of both relief and rehabilitation was largely entrusted to the States, the available funds and the administrative policies of the various States, as well as differences in standard of living and employment status, caused variations in the aid granted.

Most of the employed as well as the unemployed heads of farm families on general relief rolls received work relief in June 1935. The presence on work relief rolls of farmers still operating their farms indicates either that other members of their families could attend to the farm duties or that their farming was of little consequence.

Many were normally full-time farmers whose operations had been curtailed by the drought, and others were part-time farmers who had lost their usual supplementary employment.

Relatively fewer Negroes than whites had work relief in the two Cotton Areas, with the difference more marked in the Eastern Cotton Belt. In that area two-thirds of the white farmers on relief but less than one-half of the Negroes had work assignments.

Amounts of relief given in June 1935 in all areas combined averaged $13 for farm owners, $12 for farm laborers and tenants, and $9 for croppers. Negroes in all agricultural groups received lower relief grants than whites. Relief grants were smallest in the Appalachian-Ozark and Cotton Areas, reflecting the relatively low standard of living of those sections.

The proportion of all rehabilitation clients receiving subsistence goods (for meeting budgetary needs) and the proportion receiving capital goods (for productive purposes) were about the same (83 and 84 percent, respectively) for the total of all areas, but differences among areas were marked.

Rehabilitation advances ranged in amount from an average of $31 in the Spring Wheat Area to $416 for whites in the Western Cotton Area, reflecting to some extent the different stages of development of the program in the various areas. The average for all areas was $189.

Relatively fewer Negro than white clients in the Cotton Areas received capital goods, and Negroes received smaller advances than whites of both capital and subsistence goods.

SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF RELIEF FAMILIES

Farmers at Work on a WPA Road Project. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1537a0cb06

Farmers on relief did not differ markedly in age from all farmers in the United States. Comparison of February and June data, however, indicates that the younger farmers and farm laborers (excluding the very young group, 16-24 years of age) left relief rolls in greater numbers than did the older clients during the spring planting season.

As in the general population, owners on relief were about 9 years older on the average than tenants, while sharecroppers and laborers were the youngest agricultural groups.

Relief families were found to be larger than those in the general population. In most areas, tenants had larger families than the other groups. Negro and white households were not consistently different in size.

Although the normal family (husband and wife, or husband, wife, and children) was the prevailing type on relief, the proportion of such families varied considerably by areas and by tenure groups.

Broken families were found more frequently in the two Cotton Areas and in the self-sufficing areas (Lake States Cut-Over and Appalachian-Ozark) than in the regions where rural distress is of more recent origin. These four areas were the only ones where the mother-and-children type of family was found on rural relief in any considerable proportions.

Nonfamily men were particularly important on the relief rolls in the Lake States Cut-Over Area, and nonfamily women on relief were of significance only in the Eastern Cotton Belt, where their presence on relief rolls reflects the influence of the considerable migration of males from the South.

Households with only one worker were found more frequently in the lower socio-economic groups. The number of workers increased with the size of the family, but it was not a proportionate increase.

Migration of farmers and farm laborers evidently increased during the drought and depression years. This trend would indicate that mobility, rather than being a cause of the need for relief, was, at least partially, the result of the need for relief. However, there was no clear-cut relationship between mobility and relief needs.

EMPLOYMENT STATUS AND RELATION TO THE LAND

Young Couple On The Move During the Depression. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Mydans). Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1537fe7577

More than one-tenth of the farmers on relief in rural areas lived in villages, while much larger proportions of farm laborers on relief lived in villages.

Although in some agricultural regions farmers and farm laborers normally live in villages rather than in the open country, the residence distribution probably reflects to a large extent the influence of depression unemployment, which causes families to migrate from open country to village communities, with their greater promise of opportunities for employment or relief.

Nearly three-fourths of the heads of farm families on relief in June 1935 were farmers by usual occupation, and slightly more than one-fourth were farm laborers. Tenants other than sharecroppers made up over one-half of the farm operators on relief, farm owners accounted for about one-third, and sharecroppers for nearly one-eighth.

In all areas, larger percentages of tenants than of owners were on relief, reflecting the less secure economic position of tenants as compared to owners. In both Cotton Areas sharecroppers were represented more heavily on relief than either owners or other tenants.

The overwhelming majority of farmers on relief were still operating farms at the time of the survey. In general, tenants (exclusive of croppers) on relief had not been able to remain on the land to the same degree as had farm owners.

Sharecroppers on relief had a lower employment rate at their usual occupation than either other tenants or owners, and relief heads who were farm laborers by usual occupation had the lowest employment rate of all.

Few agricultural workers had shifted into nonagricultural jobs. Heads of relief households with farm experience but not currently engaged in agriculture had left the farm, in most instances, during the depression.

While farmers and farm laborers were leaving the open country for the villages, there was a tendency among nonagricultural workers to move to the farm.

This was especially true in the Lake States Cut-Over and Appalachian-Ozark Areas where loss of industrial jobs evidently caused workers to give major attention to farming in which they had formerly engaged part-time.

The poor soil in these two areas made the land easy to obtain but hard to get a living from, so that the workers had to resort to relief.

A Rehabilitation Client Poses with a Lamb and Chicken. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Lange). Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1538575a6c

The majority of the heads of farm households on relief who were unemployed or who had gone into some nonagricultural occupation had left the farm between July 1, 1934, and July 1, 1935. Few had left farming in the prosperous years 1925-1930.

The greater economic resources of owners and tenants, as compared with those of sharecroppers and laborers, are reflected in the periods which elapsed between the time they lost their usual tenure status or job and the time they appeared on relief rolls.

The average farm laborer family head on relief, who was no longer employed as a farm laborer, was accepted for relief only 3 months after the loss of his usual type of job, and the average sharecropper, no longer employed as such, remained off relief rolls for only 5 months after losing his cropper status.

Displaced tenants and owners, however, did not receive relief until 7 and 13 months, respectively, after they had lost jobs at their usual occupation.

FACTORS IN PRODUCTION

Farmers who were unable to support themselves and their families were found to be handicapped with respect to acreage operated, livestock owned, and education attained.

The average acreage of farms operated by owners and tenants on relief was much less than that of all owner and tenant farms reported by the 1935 Census of Agriculture.

The average acreage reported in June for both groups was much less than that in February, indicating that farmers with larger acreages had been able to become self-supporting or to go on rehabilitation rolls more readily than those with smaller farms.

This situation may be taken to indicate that as recovery in agriculture becomes more general the relief group will contain a larger proportion of chronic or marginal cases as measured by size of holdings.

Many farmers with adequate acreage were hampered in their efforts at self-support by lack of sufficient livestock. From a study made as of January 1, 1934, it is evident that fewer farm operators on relief owned livestock than farmers not on relief, and that the relief clients who did own livestock had fewer animals.

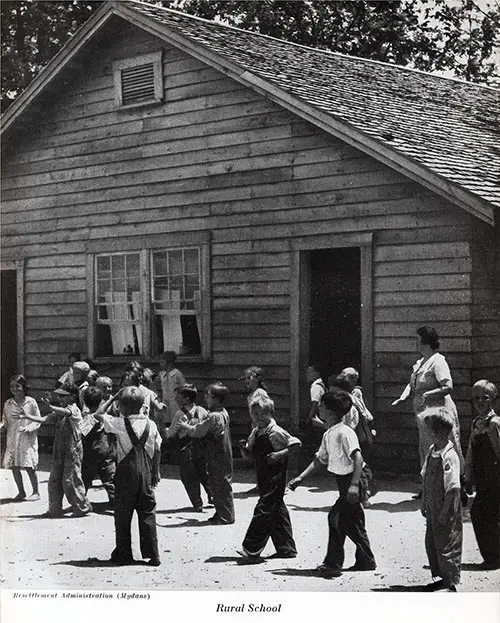

Children Playing Outside at a Rural School During the Depression. Photograph by the Resettlement Administration (Mydans). Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 15386e87c5

The farm families' need for Federal assistance was not caused by lack of agricultural experience. The great majority of the agricultural workers on relief and rehabilitation reported 10 years or more of farm experience.

One measurable index of personal ability of farm families on relief is their educational attainment. A study made as of 1933 showed that heads of rural relief families had consistently received less schooling than their non-relief neighbors.

In the present study, the majority of the heads of open country households on relief in October 1935 had not completed grade school. In no area was the average schooling higher than the eighth grade. However, the younger heads of open country households were better educated than the older heads, reflecting the trend toward increased educational opportunities in rural areas.

COMPARISON OF RELIEF AND REHABILITATION FAMILIES

When rehabilitation clients are considered separately from farm families receiving relief, some of the expected differences between the two groups do not appear.

Neither the older nor the younger relief heads and neither the larger nor the smaller relief families appear to have been consistently selected for rehabilitation.

Nor is there any evidence that the number of employable persons in the household influenced selection of families for rehabilitation. Relative stability of residence also was apparently not a determining factor.

On the other hand, in contrast with relief families, practically all rehabilitation clients lived in the open country. Also, the proportion of farm laborers was smaller among rehabilitation clients than among relief families.

Size of farm was evidently a criterion of selection, the farms of rehabilitation clients being larger than those of relief families in most areas. Some tendency to select normal families was evident.

Unattached women especially were almost unknown among rehabilitation clients, although unattached men, mother-children, and father-children families were accepted in considerable numbers in a few areas.

The rehabilitation program was primarily agricultural, but only 89 out of every 100 rehabilitation clients on the rolls in June 1935 were farmers or farm laborers by usual occupation. All but 2 out of every 100, however, had had agricultural experience.

RELIEF TRENDS

The estimated number of farm operators in the United States receiving Federal assistance, including emergency relief, advances under the rehabilitation program, and Works Program earnings, increased from 417,000 in October 1933 to 685,000 in February 1935 and then fell to 382,000 in October 1935.

During the last months of 1935, the downward trend in the number of farm operators receiving these types of Federal assistance was reversed as needs increased during the winter season. By December, 396,000 farm operators were receiving aid under the 3 programs.

In February 1935, when the relief load reached a peak in rural areas, nearly 1,000,000 farm families in rural areas alone, including those of farm operators and farm laborers, received general relief grants or rehabilitation loans.

The largest single factor accounting for the peak relief load in February was drought, which resulted in crop failures and loss of livestock.

Farm families left the general relief rolls rapidly after February 1935, with the expansion of the rural rehabilitation program and with increasing agricultural prosperity. Of all agricultural cases on relief in February, only 42 percent were carried forward through the month of June, the remainder being closed or transferred to the rural rehabilitation program.

Between July 1 and December 31, 1935, 551,000 farmers were removed from the rolls of agencies expending F. E. K. A. funds. About 186,000 of these found employment on the Works Program and 37,000 were transferred directly to the Resettlement Administration.

Of the 328,000 families completely removed from Federal aid, it is estimated that about half became at least temporarily self-supporting, largely through sale of produce or through earnings at private employment, and that the other half received aid from State or local funds or were left without care from any agency.

The temporary nature of the self-support obtained by many of the families in 1935 is indicated by the fact that out of 215,000 farm operator families accepted for aid between July 1 and December 31 by agencies expending F. E. R. A. funds, four-fifths were former relief cases returning to the rolls.

The reasons for opening relief cases in the July-October period are also significant, indicating that improvement in economic conditions had not been sufficient to offset the effects of the 1934 drought and other factors causing rural distress.

Crop failure and loss of livestock were reported most frequently as reasons for applying for relief. Loss of earnings from employment was the second most important reason given—seasonal employment had come to an end, or earnings had become so low that supplementary relief was required.

Other families came on relief which had been existing on savings for some time and which listed exhaustion of these resources as their reason for applying.

Increased needs with the approach of winter, loss of assistance from relatives and friends, failure of landlords to continue advances to croppers after the cotton harvest, appropriation of crop returns by creditors, and destruction of property by local floods were other reasons for opening of relief cases.

PROGRAMS OF RECONSTRUCTION

Any program for the reconstruction of American agriculture must take into account the conservation of human values as well as of soil and other natural resources. It must also be adaptable to the peculiar regional needs of different parts of the country.

Combined farming-industrial employment, proposed as a partial remedy for farm problems, is limited by the location and hours of industry. Retirement of sub-marginal lands from agriculture is an obvious necessity, but financial and legal difficulties stand in the way of measures which would be immediately effective.

View of Eroded Cropland. Photograph by Soil Conservation Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 1538cf53f8

Restoring fertility to eroded or exhausted soil is a sound measure of economic reconstruction, and a program to control surplus production is necessary to secure economic stability for farmers. Crop control can be successful, however, only if planned in such a way that agricultural production is adjusted to rural population trends.

For some areas, the reform of the tenant system and the arrest of the increase of tenancy are of paramount importance, since tenancy has proved to be a stumbling block in the path of such constructive efforts as crop diversification, soil conservation, and cooperative marketing.

Equally important in agrarian reconstruction are programs for the conservation of human resources. The needs of destitute farm families in the past few years have been met on an emergency basis by direct relief, work relief, and rehabilitation loans and grants.

Direct relief, whether in the form of E. R. A. benefits, State or local relief, or Resettlement grants, is often best suited to the needs of farmers for temporary assistance, even if it creates no lasting values. Work relief has the disadvantage of taking the farmer away from his land unless it is limited to off-seasons or to non-farming members of the family.

Rural rehabilitation loans are desirable for many farmers since they provide the necessary credit at a reasonable rate of interest, farm plans worked out to fit the individual farm, and advice and supervision in the execution of these plans.

Guided migration is a basic need in rural reconstruction. Although the Government cannot arbitrarily move people out of blighted areas, it can offer advice to farmers who wish to leave an area in which they cannot support themselves.

WPA Workers Building a Farm-To-Market Road. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1937. GGA Image ID # 15392b13b4

Cooperation is recognized as one of the hopes of the smaller farmer in marketing and purchasing, in owning machinery and lands in common, and in meeting farm and home problems. Education to awaken the desire for a higher standard of living is another means of social reconstruction.

The improvement of educational and other institutions in rural areas, however, calls for better financial support than is now available. Equalization funds are needed for health, education, and public welfare to reduce the financial inequalities between rural States and States which contain points of financial concentration—between rural counties and industrial cities.

The more fundamental measures for building a superior agrarian civilization in the United States are long-time measures, not planned for immediate results. Furthermore, they require national coordination and Federal financial support. Successful rehabilitation cannot be accomplished without a continuing course of action, uninterrupted by sudden shifts of policy such as have characterized relief and rehabilitation programs during the depression years.

End Notes

Note 1: Research Monographs I and II

Note 2: For details of the sampling procedure, see appendix B

Note 3: The State sample was based on 31 States, but Arizona was not included in the June survey.

Note 4: A farm is defined as having at least 3 acres, unless its agricultural products in 1929 were valued at $250 or more. Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population Vol I, p. 2.

Note 6: This procedure for determining current employment was necessary ns case records were not kept up-to-date with respect to employment status. It Is Justified by the fact that June is a peak month for agricultural employment and farm operators and laborers employed in February, a slack month, would normally continue their employment through the summer.

Note 7: See Beck, P. G. and Forster, M. C, Sir Rural Problem Areas, Relief-Resources-Rehabilitation, Research Monograph I, Division of Research, Statistics, and Finance, Federal Emergency Relief Administration, 1935, pp. 8 ff. This report also deals with the various aspects of the farm relief problem. However, the counties sampled differ from those covered by the present study, and the data refer to an earlier period.

Berta Asch and A. R. Mangus, Farmers on Relief and Rehabilitation, Research Monograph VIII, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1937.