Labor and the New Deal - 1936

Front Cover, Labor and the New Deal, Public Affairs Pamphlets No. 2, Public Affairs Committee, National Press Building, Washington, DC, 1936. GGA Image ID # 15114cebec

This pamphlet was prepared by Louis Stark on the basis of a study by a special committee of the Twentieth Century Fund. For details see "Labor and the Government," published for the Twentieth Century Fund by the McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Many persons speak of labor relations under the New Deal as if it were the first time in our history that the government has been concerned with economic problems. Such a view naturally prevents a clear understanding of current developments.

As a matter of fact government intervention in the eco- nomic life of a people is as old as government itself. In our own Colonial period, wages, hours, prices and quality were regulated in the interest of the dominant economic group, the farmer.

Later, the rising business groups sought governmental aid in various forms, and business demanded freedom from local control in the form of price fixing and local tariffs in order to enjoy free com- petition.

The Beginnings of Labor Legislation

As the employers grew in power the workers sought to organize for self-protection. Opposing such organization, business sought assistance from the government. The growing friction between business on one side, and the labor and farmer group on the other, forced con- cessions from the vested interests.

These concessions included a free public-school system, abolition of imprisonment for debt, mechanics' lien laws, the homestead law, regulation of hours of labor and the establishment of the Department of Agriculture.

With all social and economic groups seeking government aid, the resulting laws were hammered out on the anvil of heated controversy. The Civil War gave a great impetus to economic development and the foundations were laid for the modern industrial system.

Subsidies and high protective tariffs were the order of the day. Employers appealed to the courts to keep down labor organizations. In this period protective labor legislation was scanty and was contested bitterly by employers.

The depressions of the seventies, eighties, and nineties saw many strikes, the earlier ones under the aegis of the Knights of Labor, the dominant labor organization of the period. The general eight-hour day strike of 1886 was spectacular as was the militant Pullman strike of 1894.

There were demonstrations of the unemployed. Coxey marched his "army" of idle to Washington in 1894 to persuade Congress to issue $500,000,000 of irredeemable paper currency to be used for public works.

Farmers and Small businessmen and salaried groups united in asking for protection from organized business. They obtained some results. The Granger movement brought the first railroad regulation of the western states.

The clamor against monopoly and big corporations led to the Sherman Anti-trust Act, the first law to curb "trusts." Protective labor legislation was also enacted. In 1884 the federal government founded its Bureau of Labor and about this time set up machinery for intervening in industrial disputes affecting interstate Commerce.

With the return to prosperity marked by the Spanish-American War and America's emergence as a great power, business concentration was accelerated. Demands for protective labor legislation grew, and farmers and small business groups continued their agitation for relief from big business.

This was the "trust busting" era, marked by dissolution of the Standard Oil Company and American Tobacco Company. The period was also marked by social welfare legislation such as minimum-wage laws, prohibition of night work for women, and laws against use of industrial poisons.

With the further development of industry, labor disputes increased. Government officials intervened in these disputes. Courts were appealed to and issued injunctions against strikers.

Labor Relations During the War

When this country entered the World War, organization of labor for efficient production became a problem of national defense, and the government found it necessary to exercise unprecedented control over the nation's economic life.

Labor relations were as extensively regulated as other economic activities. Special boards were set up in different branches of the government to deal with labor relations. A Committee on Labor was established in the War Industries Board, a board of control was created for labor standards in the manufacture of army clothing.

A War Labor Board was created, comprising representatives of employers, employees, and the public, to handle labor controversies "with a view to guaranteeing the uninterrupted operation of industry and the maximum of war materials."

The principles governing labor relations during the war were very similar to those developed later under the New Deal. Full recognition was accorded to employers to organize into trade groups and to employees to organize for collective bargaining.

Graph of Industrial Conflicts -- Strikes and Walkouts and the Workers Involved for the Year 1916, 1919, 1921, 1930, and 1935 by Pictorial Statistics, Inc. Labor and the New Deal, Public Affairs Pamphlets No. 2, Public Affairs Committee, National Press Building, Washington, DC, 1936. GGA Image ID # 1512806395

The period was marked by agitation to prohibit strikes by state law, but the federal government frowned on this policy. After the war there was a business recession in 1920, an upturn in 1921 and a prosperous period until the fall of 1929 when the great depression began.

Demands then mounted for government intervention. Though the Hoover administration opposed government interference in economic activities, it was compelled to act by forming the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Even before the depression the farmers had forced creation of the Federal Farm Board in 1929.

The Beginning of the New Deal

But artificial attempts to stimulate production failed to stave off the collapse of the banking system in 1933 when President Roosevelt assumed office. The stage was set for widespread government intervention in business, in industry and in agriculture.

On all sides confidence in individual initiative had been lost. Even con- servative business interests, which in ordinary times would have resisted such intervention, cooperated in extending the functions of government. Most of the new agencies created since the crisis of 1929 were given wide powers.

The Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the Tennessee Valley Authority were authorized either to subsidize or undertake economic activities. Another group was commissioned to determine and supervise the conditions under which important activities were to be conducted.

Among these were the Petroleum Administrative Board and the Na- tional Recovery Administration, the latter agency being the key pillar of the New Deal.

Section 7a of the NIRA, giving labor the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of its own choosing, provoked a storm of controversy.

Many employers, alarmed at the prospect of being called upon to deal with independent trade unions, fostered "company unions" with which they could bargain collectively.

These organizations, already in existence to some extent, multiplied with great rapidity. They were encouraged by employers who expected to be able to control and dominate them and limit their functions in such a way as to discourage genuine collective bargaining.

Naturally they were bitterly opposed by the regular labor movement. The issue was drawn between employees and employers over such questions as the right to organize, the right to represent employees, the alleged discrimination against trade union members, and the alleged unlawful acts on the part of employers arising out of the formation of company unions.

Formation of the National Labor Board

The National Labor Board, the first of the national agencies to handle labor disputes, was created in August 1933, to "consider, adjust and settle differences and controversies."

The Executive Order of December 1933, empowered the board to "settle by mediation, conciliation, or arbitration all controversies between employers and employees." Senator Wagner, representing the public, was chairman and the other members were drawn from organized labor and industry.

However, the National Labor Board was without statutory basis and without explicit enforcement power. Of necessity its policy was one of persuasion, relying on the force of public opinion.

It was primarily an administrative agency with the duty to inquire into facts with regard to alleged violations of Section 7a and to make recommendations to the enforcement agencies of the federal government.

Regional boards, agents of the National Board, assumed jurisdiction and mediation in all cases involving violation of Section 7a and in cases involving code violations if a strike was in progress or pending.

Experience with the bi-partisan National Labor Board was not wholly satisfactory, and on June 29, 1934, President Roosevelt created the National Labor Relations Board. Since the work of the new board was to be quasi-judicial, it was decided to limit its personnel to neutral, impartial persons technically qualified to handle labor relations.

Throughout its history the major emphasis in the board's function was that of mediation. Settlements between parties were encouraged and if this was not possible the contending groups were urged to agree to arbitration.

Under the authority of a Congressional resolution which he invoked in creating the National Labor Relations Board, the President also created the National Steel Labor Relations Board, the Textile Labor Relations Board and the National Longshoremen's Labor Board.

The National Labor Relations Board took exclusive jurisdiction over all controversies arising under Section 7a except those under jurisdiction of the three above-mentioned boards. At the same time industrial boards were set up under the codes of fair competition to handle disputes within their own industries.

In June 1934, the Railway Labor Act was amended. The amendments to the Act made clearer than the provisions of Section 7a the rights of employees to self- organization and collective bargaining and the obligations and prohibitions imposed upon management, in regard to such matters as "outside representatives, majority rule, use of funds by carriers for labor organization."

A National Mediation Board, created by this amended act, was authorized to investigate disputes among employees as to who are their representatives. Company unions declined on the railroads after the passage of the Act.

The first National Labor Board held that collective bargaining involved an obligation by employers to discuss differences with their employees and make every reasonable effort to reach an agreement in all matters in dispute. The second board, the National Labor Relations Board, went further.

It said that bargaining in good faith meant not only consideration of employees' proposals but also submission of counter proposals and the exertion of every effort to reach an agreement binding the company for an appropriate term.

The question of union recognition was a vital one and arose in nearly all cases presented to the board. Since the law contemplated collective bargaining between employers and employees, it soon became a question of which type of organization employers would bargain with.

To forestall dealing with regular unions and yet fulfill the collective bargaining provisions of the NIRA, employers reorganized existing company unions or set up new ones. The board conducted many elections for collective bargaining representatives and certified those candidates who received a majority of the votes.

In some cases the board ruled that by establishing company unions the employers had interfered with their employees' right of self-organization.

In the Houde Engineering Case, the board held for the first time that an employer may not bargain with a minority but must bargain with a majority as the exclusive collective bargaining agency of all employees. These decisions led to many legal controversies and the board was enjoined in a number of instances.

Strikes and Labor Disputes

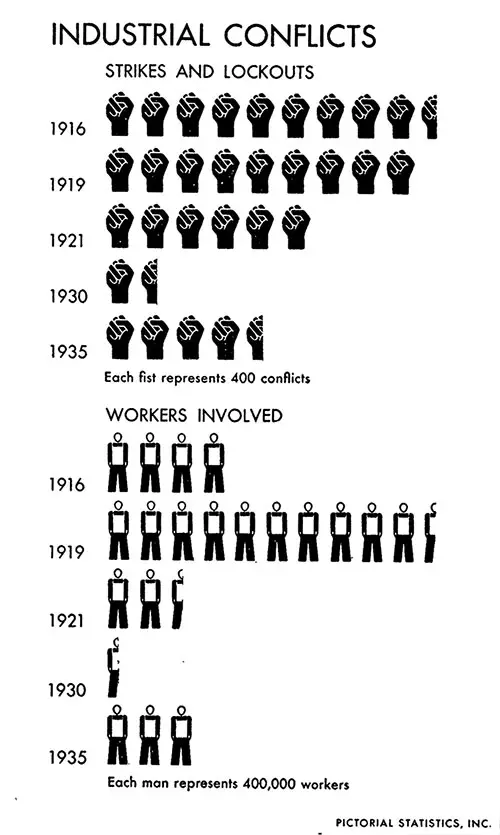

Contrary to popular impression, neither the number of strikes nor the number of workers involved were as great during the period of the NRA as in some former years.

Statistics show that in other economic crises, when there was no such government intervention as existed during the war and the NIRA periods, there was intense labor unrest and an even larger number of strikes.

It is dangerous, however, to draw definite conclusions as to the effect of government intervention on strikes. There are so many variables which determine strikes that it is often impossible to attribute their occurrence to a single factor.

Thus while government intervention of itself may not increase the number of strikes, an ambiguous law or one which confers upon employees' rights which employers are not prepared to concede, may, for a time at least, tend to foment labor disputes.

While study discloses the fact that in the year 1934—the only full year of the NRA period—there was a decided increase over 1932 both in the number of strikes and the number of workers involved, it also reveals that there have been other years of far greater strike activity.

The number of disputes in each year from 1916 through 1921–ranging from 2,400 to 4,500—stood higher than in 1934 when 1,742 were recorded. From the point of view of workers involved the year 1919 was the peak, with 4, 160,348 involved—almost four times as many as in 1934 when 1,353,912 employees were involved.

The years 1916, 1920 and 1922 all show a larger number involved than 1934. A new trend toward a reduction in the duration of industrial disputes began in 1928 and reached the lowest point in 1933.

This is explained in part by the mediation activities of the various government labor boards. Their intervention in the early days of the NRA not only averted a large number of strikes but aided materially in bringing them quickly to an end.

While from the point of view of duration, disputes appear to be becoming less serious, the average number of workers involved in each dispute seems to be increasing. In 1933, the average number of persons involved in disputes was 520 as compared to 3ol in 1931—a gain of about 73 per cent. In 1934 the number of persons involved per dispute jumped to 777.

Invalidation of the NRA

In May 1935 the Supreme Court invalidated the NRA. Immediately there was considerable agitation from the labor groups for some law that would replace section 7a of the NIRA. With the NRA the National Labor Relations Board as well as the various special labor boards in steel, textile, and petroleum industries, had passed out of the picture.

In June 1935, upon the insistent demand of labor and its sympathizers, Congress adopted the National Labor Relations Act sponsored by Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York and Representative William Connery of Massachusetts.

This law created a National Labor Relations Board of three neutral members, reiterated the guarantee of collective bargaining that had been written into the NIRA, but went much further by specifically providing against interference by an employer in the self-organization of his employees.

This was done by writing into the law what are referred to as unfair labor practices. An employer, under Section 8 of the Act, is prevented from coercing his employees in their right to self-organization, from contributing financially to any labor organization, from discriminating against union members in hiring or tenure of employment, from discharging an employee because he has filed charges under the Act, and from refusing to bargain collectively with his employees.

The application of the act was limited to firms whose business affects interstate commerce. The law was written in this way so as to conform with the Supreme Court ruling in the so-called Schechter "sick chicken" case.

Hardly had the National Labor Relations Board begun its activities in October 1935, before it met with the opposition of employers who attacked the law as un- constitutional. When the board, at public hearings, refused to dismiss cases on constitutional grounds employers frequently refused to present their cases or did so under protest.

Other employers went to the Federal District Courts and obtained temporary orders restraining the board from holding hearings. The labor law did not contemplate allowing employers to hold up the board's work to the extent of preventing it from holding hearings.

It did provide, however, that after the hearings by a Trial Examiner, whose findings were upheld by the board, the latter would deposit the testimony in the Circuit Court of Appeals, at the same time issuing a "cease and desist order" and calling on the employer to refrain from unfair labor practices.

At this time, if the employer wished, he might apply for a restraining order. But the board and the labor law's proponents held it distinctly unfair to hamper them even from proceeding to ascertain the facts behind a complaint.

In several cases the Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the board's right to order hearings. These were balanced with other cases in the same court but in different jurisdictions in which restraining orders were approved. The first case before the Supreme Court on the board's constitutionality is expected to be passed upon in the winter of 1936-37.

Rise of the Trade Unions

BEHIND these recent events is a long, tortuous his- tory of trade union development. The first known instance of direct action by workers to improve their conditions was a spontaneous strike of printers in 1776.

The first recorded permanent organization of workers, a cordwainers' union, came into existence in 1792. Organized at first on a local basis by crafts or occupations and federated into local bodies, the trade-union movement expanded with the growth of the country and the widening of markets.

The early policy of the trade unions was to secure betterment of advantages mainly through their own efforts and to rely on the government as little as possible, but the World War modified this philosophy to some extent.

Under the new policy, labor demanded that the government take over the railroads and mines and other important industries and operate them in the public interest.

During the World War there were few trades or industries in which unions did not function to some extent. Following the war the employers launched an aggressive open-shop campaign which routed unionism from mass production industries, the railroad shops, and mining.

With the advent of the NIRA and the amended Railway Labor Act of 1934, however, the unions were given a new impetus, being strengthened where they were already operating and gaining at least a foothold in practically every trade and industry, including the mass- production industries and the important service trades.

The American Federation of Labor

Today trade-unions are to be found in every industry and every geographic area. It is estimated that the total union membership in 1934 was 4,200,000 out of the 32,000,000 wage earners eligible for organization.

The various unions are, in the main, members of the American Federation of Labor which is "a loose federation under which each international and national union has complete trade autonomy." Unions calling themselves "international" have members in Canada; a few have members in Mexico.

The federation also has state and city federations which are permitted to accept into membership only local unions that are part of national and international unions. The railway transportation unions are not affiliated with the A. F. of L.

These are the engineers, firemen, conductors and brake- men's organizations. There are also independent unions in shipyards, radio and electrical plants and among agricultural workers.

The charter which the federation grants each national or international union describes the field of operations allotted to that organization. That field is known as the union's "jurisdiction".

The unions are forbidden to encroach on each other's "jurisdiction". For example, the miners' union has the authority to take within its fold all workers "in and about the mines".

If, let us say, the machinists' union should try to induct men pursuing that calling in a mine the miners' union would resent it on the ground that its "jurisdiction" covers all employees including the machinists.

No feature of American unionism has been so severely challenged as has union structure. The problem presented by the need to organize the mass production industries has forced the A. F. of L. to consider revising its structure to meet the new situation.

When the present unions were founded, during the transition from handicraft to mass production, the skilled worker predominated. Each worker could per- form all the operations in the production of a particular commodity.

This is the kind of worker that the term "craft" describes, and the early organizations of workers could truly be described as craft unions. As industry progressed, especially with the impetus of the Civil War, production began to be reorganized.

This reorganization took two general forms. Most of industry became factorized, which meant the introduction of machinery and the concentration of a considerable number of workers under one roof and employed by one firm.

Where machinery could not supplement or replace hand labor, the processes on the commodity were divided. Thus in the manufacture of clothing certain workers were required to specialize in sleeve making, others in pressing.

This division of labor accomplished the same purpose as had machinery; skilled occupations were broken up into specialized operations whether performed by hand or machine.

Mass production with the belt and conveyor is a more recent development that has accentuated the problem. This new type of production gave rise to a new problem of organization: the formation of industrial unions.

An industrial union is one that includes all workers in and around a plant, skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled. Al- though the predominant group of employees in a mass- production industry factory may perform specific operations; they do not belong to any particular craft calling and are termed production workers.

There are, however, in the plant, small groups of craft workers who form an auxiliary class, such as maintenance and repair crews.

Industrial vs. Craft Unionism

With the impetus given by the NIRA to organization in the mass production industries—automobile, rubber, cement, aluminum—the question of industrial unions again became a major issue in the labor movement.

That issue was carried to the 1934 convention of the A. F. of L., which decided to form industrial unions in the automobile, cement and aluminum industries; but at the 1935 convention the industrial unionists, led by John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers of America, claimed that the charter issued to the automobile workers shortly before the convention opened was not an industrial union charter.

This led to a heated debate and when the votes were counted the industrial unionists had about 40 per cent of the ballots. This meant that the official policy of the federation as interpreted by the craft union leaders, would permit the formation of unions of production workers in the mass industries, but the craft leaders retained the right to claim jurisdiction over their mechanics in these mass production plants.

The movement for complete industrial unionism did not stop when the 1935 convention concluded. A month later Mr. Lewis and the leaders of seven other unions who favored industrial unionism formed the Committee for Industrial Organization and set up an office in Washington to disseminate their ideas.

The Executive Council of the A. F. of L., in January 1936, ordered the committee to disband as it feared that the eight union group was setting up a rival to the federation, but the committee refused to dissolve and denied that it was interested in building up a rival organization, claiming it was intent only on assisting the federation to organize large industrial unions in the mass production industries.

In essence the craft unions are said to fear that if a large industrial union movement attained headway, comprising workers in the steel, automobile, rubber, aluminum, cement and other industries the balance of power in the A. F. of L. would pass to the industrial unions.

The craft union leaders who have dominated union policy for 55 years would be removed from control and the labor movement would adopt more aggressive organizational policies and probably more in the direction of building up a labor party, based on a broad appeal to all workers "of hand and brain".

The great bulk of the organized workers in these mass production industries have been organized into "federal" unions, one for each plant. A federal labor union consists of employees who are not under the jurisdiction of any national or international union.

Affiliated directly to the A. F. of L., they look for guidance and advice and protection to the parent organization. A federal labor union is an incipient industrial union. Craft or trade lines have been disregarded.

The question naturally arose whether the workers in these new unions should be permitted to continue on an industrial basis or be divided up among the various craft and trade unions having technical jurisdiction but which did not organize them.

If the craft and trade idea prevailed, the workers in the automobile industry, for example, would be divided into a dozen or more unions, such as machinists, electricians, blacksmiths, sheet-metal workers, boiler makers, molders, pattern makers, polishers, painters, upholsterers—to mention only the more important unions claiming jurisdiction over automobile employees.

This procedure would apply to all the mass- production industries. Most of the workers prefer to remain in the federal labor unions with the idea that these be combined into industrial unions.

The Company Union

Employers, in order to safeguard their interests in dealing with their organized workers, have, as we have seen, organized associations of their own. Most of them resisted demands for collective bargaining, insisting that conditions of employment should be determined between individual employers and individual workers.

They held that collective bargaining interfere with the constitutional right of the individual worker to con- tract for his services, that collective bargaining was a monopolistic practice interfering with unrestrained business dealings, and they objected to outsiders interfering in the conduct of their business.

With the advent of the NIRA and its Section 7a legalizing collective bar- gaining by statute, employers declared that the employee representation plan furnished a means by which workers might attempt to bargain collectively with the management.

It is to be noted that stimulation of independent as well as company unions resulted from conditions created by the World War. At that time the government's policy was to recognize unions and the right of collective bargaining.

The great unrest caused by the rising tide of industrial activity, accompanied by mounting living costs, made employers seek in company unions the machinery for settling disputes and maintaining peaceful labor relations.

Company unions are serious competitors for membership with the regular or outside trade unions. It is estimated that about 2,500,000 workers are now organized under such plans, compared with a total trade union membership of approximately 4,200,000.

In contrast to the total number of wage-earners in the United States, however, the proportion organized in both company and trade unions is relatively small—only 6,700,000 out of approximately 32,000,000.

In the period since the War membership in company unions has grown rapidly, while that of the regular unions has not. For example, comparable figures show that the number of employees in company unions increased from 404,000 to 1,300,000 between 1919 and 1932, while the membership of the American Federation of Labor fell from 3,300,000 to 2,500,000 in the same period.

An especially rapid growth in company unions has occurred since the summer of 1933. This has been attributed largely to the influence of Section 7a of the NIRA under which employees were given the right to bargain collectively and to organize some form of collective bargaining agency.

At present, the outstanding anti-union employers' associations, headed by the National Association of Manufacturers and the Chamber of Commerce of the United States are urging the company union as against the trade union.

The Congress of American Industry held in conjunction with the National Association of Manufacturers in 1934, declared:

The effect of recent labor legislation and decisions of labor boards has been to build up in the public mind the thought that in labor relations the interests of employers and employees are in conflict and that the only method whereby these interests can be reconciled is through enforced collective bargaining.

he very term "collective bargaining" as now used, denotes to many the idea of two private parties each with a separate and distinct interest, endeavoring by bargaining to obtain what he considers an advantage over the other. Proper relationships cannot be established on such misconceptions.

Signs of revolt among the company unions are already appearing. Recently eleven company unions in separate plants of a large steel corporation held a convention, decided to ask for a wage increase and made other demands which displayed certain characteristics of independence not usually attributed to company-dominated unions.

If this tendency toward independence increases, it is possible that ultimately the company union groups in separate plants or mills may unite in large industrial unions.

Employers in some industries fear that the company unions may yet prove a Franken- stein that will override their efforts to keep them in- nocuous for genuine collective bargaining.

Company unions as a whole face a hard struggle for existence if the provisions of the Wagner National Labor Relations Bill are enforced, because of the provisions that forbid employers to finance, dominate or in any way control employee representation groups. It is doubtful, however, if organized labor, without government intervention, is strong enough to eliminate company unions in the big corporations.

Problems in Collective Bargaining

Trade Unions

Collective bargaining offers the best approach to satisfactory employer-employee relations by providing a worker with a status and a stake in his job, but it must be freely admitted that collective bargaining is not a panacea for labor ills.

In the face of resistance by the employers, labor's efforts to obtain collective bargaining are likely to cause interruption to trade. Until adequate adjustment machinery is created, conflict is frequent and inevitable.

Effective collective bargaining necessitates a strong, disciplined union movement under competent leadership. Such a union movement does not at present exist in the United States.

The reasons are inherent in American tradition and history, and in the structural weaknesses of such labor unions as are now operating.

In Europe, until the advent of the totalitarian state in some countries, labor was a closely-knit class aware not only of its strength but of its group interest and it has organized into political parties, fraternal and educational organizations, all of which have functioned as part of the labor movement.

In the United States, however, the worker has never felt himself as different from his "boss", except in the matter of income. In the United States also, the employee identified himself largely with the middle and property-owning class.

This lack of labor consciousness resulted naturally enough from the peculiar progress of the United States, founded on democratic principles, whereas European countries were stratified into class groupings.

The American land policy under which free land was to be had for the asking offered security which was unprecedented in history. In a land of infinite promise a labor movement seems out of place.

The worker feels that he does not need his own political party, his own fraternal or social organizations, nor a class-conscious workers' press. This explains a fundamental weakness of American organized labor.

The worker has always been torn be- tween loyalty to his union and his identification with other organizations or influences hostile to trade unions. There are enormous difficulties in the way of unionization in the United States.

The movement is handicapped by the extent of the country and the size of the population. To organize an industry like steel means reaching hundreds of thousands of employees over a large area.

In the 1919 steel strike 400,000 workers were involved, but the walkout was abandoned after three months. Migration of industrial units is another effective method of checking unionization. Thus the textile industry in moving South has done so partly to tap the reservoir of low-paid unorganized labor.

Technological progress, replacing of men by machines, the replace- ment of skilled by unskilled men, also affects unionization. Internal factors in union make-up also retard growth of the movement. Most unions have failed to devise a successful technique for organizing workers in the mass production industries.

Company Unions as Bargaining Agencies Where the trade union was unwelcome, the company union or employee-representation plan offered itself as the obvious substitute.

The sudden appearance of company unions in plants that had always adhered to an individual-bargaining method, especially in the mass-production industries, merely indicated in most cases an attempt at formal compliance with a collective- bargaining law for the purpose of avoiding bargaining with a trade union.

Difficulties, however, immediately arose over the fact that the recovery act did not merely give employees the right to organize and bargain collectively, but also provided that in the exercise of this right employees were to be free from the interference, restraint or coercion of employers.

Most of the troubles involved the newer company unions. Only an insignificant number of disputes concerned employee representation plans which were functioning prior to 1933.

These are the essential characteristics of company unions:

- Their jurisdiction does not often extend be- yond a single business enterprise or plant;

- Management is aware of, and approves their formation and cooperates in it to some degree;

- They usually embrace all classes of employees in a plant or concern rather than a craft, as is usual with trade unions.

- The membership is usually free of financial obligations.

- Membership is coincident with employment; and

- The power of referendum to the membership on acts of their officers is usually lacking.

On the basis of an intensive investigation of 80 Specific plans by a committee from the Twentieth Century Fund, the company unions were found to be in- adequate agencies for collective bargaining because direct or indirect employer influence can, in the nature of this type of organization, never be entirely absent.

The degree to which such influence is present varies greatly between one plan and another. Employees do not always suffer economic injury because of employer influence in the bargaining organization.

They may enjoy conditions as good as those enjoyed by like workers in competing plants where there is no organization or where there is trade union jurisdiction.

Furthermore, company unions often supply effective machinery for adjusting grievances and correcting abuses when none would otherwise exist.

In this respect they afford the employee a means of protection which he can seldom achieve under conditions of individual bargaining.

There are many reasons why company unions have failed to function as genuine collective bargaining agencies.

Company union representatives are on the employer's payroll and if they are too aggressive in presenting grievances they may be disciplined, discharged or otherwise penalized. The vital necessity for an employee to retain his job makes it impossible for him to represent his associates as energetically as he might if he were protected by an outside organization.

The fact that the expenses of the company unions are borne by the management tends to fetter the employee organization. Company unions can rarely back up their demands by a strike threat, for strikes must be financed and the company unions have no dues.

Bargaining equality cannot be attained where one party has disproportionate economic power. In company unions the bargaining representatives are usually chosen from the ranks of the employees though by the nature of their lives and occupations they cannot be equipped to contend successfully with the specialists hired by the employers.

The trade union can use agents not on the company's payroll, men experienced in collective bargaining and may also hire outside experts.

Company unions have no contacts outside the single plant and so cannot obtain the support of other workers and organizations. Their difficulties are thus increased because they cannot conveniently obtain firsthand knowledge of conditions in the industry.

Finally, company union plans do not ordinarily lead to signed agreements for fixed periods of time as do those under the usual trade union practice. A two to one vote in favor of trade unions as opposed to company unions was cast by workers where United States government labor boards conducted elections to determine collective bargaining agencies, except in the automobile industry where the elections showed a four to one majority against both independent and company unions and in favor of unaffiliated representatives.

This disparity in results was explained in part by the fact that elections held by the boards other than in the automobile industry usually involved the question of union recognition and were held at the request of trade unions, which naturally did not ask for them unless they felt that they had at least a reasonable chance of winning.

In the automobile industry, on the other hand, the elections were held on the initiative of the Automobile Labor Board, and on ballots that made voting for an organization less likely than in other board elections.

Conclusions

Although dissenting from some of the provisions of the Wagner-Connery labor relations bill, the report of the Twentieth Century Fund Committee endorsed the main purposes of that measure.

It differed from the Wagner-Connery bill chiefly in recommending complete independence of the national labor board from the Department of Labor. In studying the role of the government in labor relations, collective bargaining between employers and their employees stands out as of predominant importance.

From a difficult birth in the days when the banding together of employees to make demands on their employers was looked upon as an unlawful conspiracy in restraint of trade, the practice has grown to its present stature.

The policy of the United States to protect and foster the right of employees to organize and to choose representatives for collective bargaining without interference, restraint or coercion has been declared and reiterated by Congress in the Railway Labor Act of 1926, in the Norris-La Guardia Anti-Injunction Act of 1932; in the Bankruptcy Act (Interstate Railroads) of 1933; in the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1934 and in the amended Railway Labor Act of 1934.

The effective development of collective bargaining presents the most immediately pressing problem in the relation of the federal government to labor.

As the organization of workers for collective bargaining is only a means to an end—the establishment and observance of written agreements—such agreements should, if the parties to the agreement so desire, and after registration by an appropriate government agency, be sanctioned by giving to such agency appropriate power to enforce the agreements.

In any society in which employers and employees retain a large measure of freedom, strikes and lockouts are likely to occur. The spread of organization for collective bargaining is not likely, in its early stages at least, to diminish the number of such occurrences.

Therefore the government's policy of guaranteeing collective bargaining should be supplemented by improved machinery for handling industrial disputes because the government will find it necessary to intervene in such disputes whenever they seriously threaten to obstruct the free flow of interstate commerce and threaten the general welfare.

There has been considerable confusion of function and overlapping of authority among the national labor relations agencies. It is essential to separate governmental mediation in labor disputes from the administration of labor law, and it is clear that the problem requires for its solution other agencies that can take care of minor law infractions.

These considerations point to the desirability of a permanent federal labor law applicable to all cases that affect interstate commerce or threaten the general welfare.

The specific recommendations of the committee follow:

Enactment of a federal labor law applicable to all industries (except railroads which are covered by the Railway Labor Act) guaranteeing to the workers freedom of association, self-organization and choice of representatives, and designed to encourage and sanction collective agreements with respect to hours, wages and working conditions.

The law should declare it unlawful:

a. For anyone to intimidate or coerce employees in the free exercise of their right to organize and to choose their own representatives for collective bargaining;

b. For an employer to discriminate against or in favor of an employee for any activity in connection with any employee organization; but the employer shall have the right to make an agreement requiring membership in a particular employee organization if that organization represents the majority of employees in a bargaining unit;

c. For an employer to interfere in any way with the formation or administration of any collective bar- gaining agency of his employees or with the choice of employee representatives for collective bargaining or to contribute toward support of any bargaining agency.

d. For an employer to discharge or otherwise discriminate against an employee because he has filed charges or given testimony under the act.

The federal labor law should provide for a Federal Labor Commission, a permanent and independent governmental agency which shall have the following functions:

(a) jurisdiction of all violations of the act;

(b) jurisdiction over disputes that arise between or among employees on questions of employee organization or representation, with power to decide what is the appropriate unit of employee organization for collective bargaining and to hold elections and otherwise determine and certify the duly chosen representatives of such units;

(c) the power to register at the joint request of the parties and to enforce trade agreements of definite duration freely entered into by employers and their employees.

The commission should not be a policy making body but should confine itself to administering policy as defined by the law. It should be given power to enforce its decisions by cease and desist orders enforce- able in the United States Circuit Court of Appeals.

It should have full power of investigation and examination of witnesses, with the right to subpoena witnesses, payrolls, and other records and to administer oaths.

Representatives chosen by a majority of employees in any bargaining unit should be the exclusive representatives of all the employees in that unit for collective bargaining as to wages, hours, and other basic working conditions.

But individuals and minorities have the right to present grievances to their employers which do not affect the wages, hours, or working conditions established by collective agreement.

A federal mediation agency should be created, or existing federal mediation agencies should be strengthened. Such agency or agencies should have power to mediate in all industrial disputes which obstruct or threaten to obstruct the free flow of interstate commerce or threaten the general welfare, and failing success, to recommend the appointment of a special investigating commission by the President.

In order to provide a reasonable period within which disputes that might give rise to strikes or lockouts may be mediated the law should oblige employers and employees to give fifteen days' notice of all changes or demanded changes in wages, hours, or working conditions except where an agreement may exist for a different period of notice or where the employees have no bargaining representatives in which case they need not give notice to the employer.

Mediation should begin when either side gives notice and if mediation fails and the disputants do not wish to submit to voluntary arbitration, the facts should be certified to the President if the dispute is likely to create a national emergency or seriously interfere with the flow of commerce among the states.

The President would then be required to appoint a special commission to make a report and specific recommendation for settlement. These recommendations would not limit the right to strike or lockout.

A special commission should be created to study the practices of employers and employees in collective bargaining and industrial disputes, as well as the operations of the agencies through which these relations are carried on, in order that it may recommend to Congress further definitions of such unlawful practices as involve unfair interference on the part of employers with employees or on the part of employees with employers.

The Wagner-Connery Bill

The Wagner-Connery bill was proposed in February 1935 and adopted in June 1935. It enacted two of the main recommendations of the Fund's special committee:

(1) Guarantee of freedom to workers to organize and choose their representatives for collective bargaining.

(2) Creation of an independent semi-judicial federal labor board to enforce these guarantees and to determine, in cases of dispute, the appropriate unit of representation, and who should represent the employees in each bargaining unit.

It did not, however, provide the machinery for mediation, arbitration and investigation of industrial disputes, the registration and enforcement of collective bargaining agreements, or the appointment of a commission to study collective bargaining practices.

The Twentieth Century Fund Committee pro- posed specific amendments to the bill. These amendments were designed to give the Federal Labor Commission the power to register and enforce collective labor agreements at the request of both parties, to protect the organizing and election activities of employees from interference through fraud or violence by anyone and to give to the Federal Mediation Service, separate from the Labor Commission, all functions of mediation and the promotion of arbitration in employer-employee disputes. These amendments were not enacted.

Public Affairs Committee

THE purpose of the Public Affairs Committee is to make available in pamphlet form accurate information regarding public affairs and to place at the disposal of the public some of the resources of existing research institutions.

The following individuals compose the Committee:

- Raymond Leslie Buell (Chairman), Foreign Policy Association

- Harold G. Moulton (Treasurer), Brookings Institution

- Lyman Bryson, Columbia University

- Evans Clark, Twentieth Century Fund

- Frederick V. Field, American Council, Institute of Pacific Relations

- William T. Foster, Pollak Foundation

- Luther Gulick, Institute of Public Administration

- Felix Morley, Editor, Washington Post

- George Soule, National Bureau of Economic Research

- Francis Pickens Miller (Executive Secretary)

The members of the Public Affairs Committee are serving on the Committee in a personal capacity and not as representatives of their respective organizations. The organizations with which they are connected are in no way responsible for the policies or activities of the Committee.

The Committee has no thesis or program of its own but will serve merely as a medium for disseminating the results of research and expert knowledge regarding public issues.

It is a non-profit making organization financed during its first year by the Maurice and Laura Falk Foundation. Mr. Maxwell S. Stewart is editor of the pamphlet series. Public Affairs Committee, National Press Building, Washington, DC.

This pamphlet is the second of a series dealing with the economic and social Organization of America. It is available in quantity lots at the following prices: 0 to 49 copies, 8 cents each; 50 to 99 copies, 6 cents each; 100 to 999 copies, 5 cents each; 1,000 AND UP, 4 cents each. Postpaid Public Affairs Committee, National Press Building, Washington, DC.