Conclusions - Rural Youth - Their Situation and Prospects - 1938

Front Cover, Rural Youth -- Their Situation and Prospects, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1531986355

Youth is an adjustment period. It is the age when most young people leave school. It is the time when they strive for economic adjustment, which frequently involves migration from one community to another.

It is a short period in the life of each individual when marriage and preparation for marriage and other social adaptations into adult life are made. During these transition years most of life's patterns are fixed.

Society's maladjustments are of particular concern when they intensify the problems of youth. To the extent that these maladjustments make a permanent imprint on the personalities of large numbers of youth, their consequences will be lasting— enduring for at least a generation.

The plight of rural youth is not a problem of the country alone. It is of vital significance to the cities as well. In one respect the crux of the rural youth problem is the relation of rural youth to city youth.

Except in periods of severe depression it is probable that urban youth could make their economic adjustments with relative ease, at least on a minimum subsistence level, if they did not face the competition of rural youth who migrate to the cities.

Death among the older city dwellers opens opportunities about as fast as urban youth mature. But the long-time rural youth problem is that of an excess in numbers in relation to a dearth of rural opportunities, a situation which becomes greatly aggravated during "hard times." Hence, rural youth must go to the cities in large numbers as long as there is any hope of employment.

During the next 15 to 20 years there will be a continual increase in the working population of the entire country. The number coming into the productive ages and automatically competing for employment opportunities, particularly with workers immediately older than themselves, will for some years be much greater than the deaths within the productive ages. As a result the intensification of the problems of youth in making their economic adjustments is likely to continue for some time.

While most rural young people encounter some difficulties in making their economic adjustments and in obtaining an adequate education and the opportunity for satisfactory personal and social development, those encountered since 1930 have been more acute than ever before.

This does not mean that the majority of all rural youth have been on relief or that all have faced insurmountable handicaps in "getting a start," but it does mean that great numbers of young people have faced serious obstacles in making their transition into adult activities.

Moreover, without definite public policies directed toward aiding young people, America is facing the prospect of successive generations of youth, among which many young people will be seriously maladjusted and some will be idle or only partially occupied throughout their mature years.

The future of American rural life, and to a large extent of urban life, rests on increased industrial production, a closer integration of industry and agriculture, and an expansion of the cultural and human services so badly needed in rural society.

Rural youth as they approach the threshold of citizenship responsibility need not necessarily face contracting opportunities. It is the responsibility of a democratic society to see that these new citizens receive a fair share of the national income in order that they may become effective consumers as well as producers and thus contribute in just measure to the prosperity of both agriculture and industry.

Rural America must choose between two courses. One is the active planning for the conservation of its human resources, recognizing the fact that with no age group will the planning produce greater returns than with young people.

The other is to let present trends continue. Until free land in the West was exhausted and the cities ceased their mass absorption, youth could escape from their home communities.

But the problems of rural youth can no longer be wholly transferred to other communities. Never has this country been faced so forcefully with the necessity of charting a course for its rural youth.

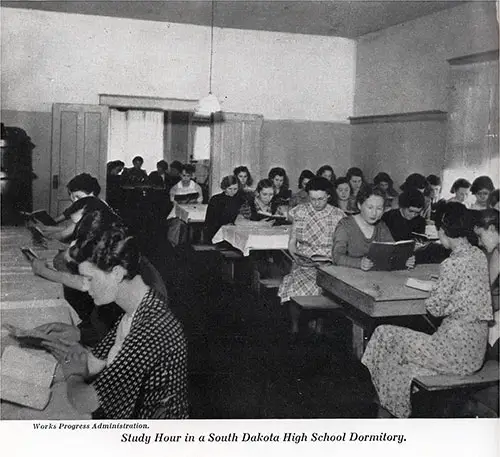

THE NEED FOR EDUCATION AND GUIDANCE

Study Hour in a South Dakota High School Dormitory. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Rural Youth -- Their Situation and Prospects, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1938. GGA Image ID # 15351eb2d5

The ability of the individual youth to make his economic adjustment when opportunities are available depends largely upon the education and guidance that may have been afforded him.

That education gives an advantage in the struggle for security and that equality of educational opportunity is an inherent right of youth are traditions in American life.

The fact must be clearly faced, however, that there is not equality of educational facilities in rural America and that the areas which supply the largest portion of the oncoming generation are those in which educational opportunities are most severely restricted.

A heavy increase in rural high school enrollment has occurred during the same years that the most serious problems of rural youth have emerged. While this enrollment may have been partly due to expanded school facilities, it undoubtedly has been in large measure a result of present-day employment conditions.

In numerous instances youth have gone to school because there was nothing else to do. Moreover, during recent years there has been a definite movement to keep youth in school longer.

This raises certain questions. Will the fact that youth attend school for longer periods solve the problems of rural youth? Or does continued attendance in the average public school of today only postpone the time when the same problems must be faced, with little better chance for successful solution? To what extent have the schools been shock absorbers for the depression? How effective have they really been in assisting youth to make their social and economic adjustments?

These queries cannot be answered categorically. They point, however, to the desirability of a redefinition of the functions of the rural schools in terms of current conditions, especially with respect to vocational education and guidance.

Guidance toward occupations is almost entirely lacking in rural areas. Youth commonly pass through the rural school curriculum with the hazy assumption that they are being prepared to enter adult life.

But the preparation they receive other than that core of knowledge recognized as general fundamental training too often has only indirect relation to their future work. Most youth enter adult occupations by chance.

Giving them greater opportunities for both general and specific occupational training and for learning more about occupational openings is a special need facing rural America.

Rural schools are responsible for the training and guidance of three broad groups of pupils: those who will go into commercial agriculture; those who will enter nonagricultural occupations in either rural or urban areas; and a third large group comprising those who under present circumstances are destined to remain in rural territory living on the land on a more or less self-sufficing basis. It is being increasingly recognized that one of the first duties of the school is the discovery of the particular potentialities and aptitudes of the developing pupil so that on reaching the youth age the individual has some idea of the vocation or vocations in which he or she could reasonably expect to succeed if given additional and proper training.

It is, of course, not to be expected that every rural high school can be equipped to train youth in a wide variety of skills, but there are certain fields in which they must provide training if a large proportion of rural young people are to have any vocational training at all.

Vocational training in agriculture is doing much to prepare youth for farming, but with all the efforts in this direction it is doubtful if at present enough youth are being trained in high schools and colleges to provide an adequate number of farmers to raise the agricultural products needed for market at the highest possible level of efficiency and at the same time to operate their farms in accordance with the best principles of soil conservation.

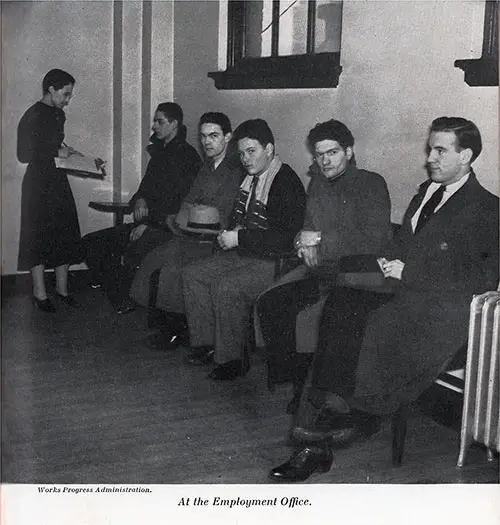

Young Americans Sit Patiently at the Employment Office During the Depression. Photograph by the Works Progress Administration. Rural Youth -- Their Situation and Prospects, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1535be0f38

That does not affect the fact that there is a "surplus" of youth on the land; it only indicates that youth are not being prepared in sufficient numbers to engage in scientific agriculture.

The rural-nonfarm youth who will enter nonagricultural occupations and the farm youth who will leave the farms receive little special consideration in the educational system.

These two groups together constitute considerably more than half of all rural youth. Usually these groups can secure only the general education provided by a standard curriculum.

Moreover, it is usually a curriculum built on the assumption that at high school graduation the young people will go on to college. This is in spite of the fact that many of the professions and white-collar occupations for which young people are being trained are at present overcrowded when judged in relation to the economic demand.

Schools have not been sufficiently aware of the fact that for youth in economically marginal families—and in recent years in families that have been on relief—the problems of social and economic adjustment are intensified.

Though some of this group of rural youth will migrate, the large number that will remain presents a continuing challenge to the schools to teach them a better way of life in their home communities.

In analyzing the educational needs of rural youth, it must be kept constantly in mind that high school facilities are not readily available for all rural youth. The above discussion respecting vocational education does not apply to many areas because even general secondary schools are lacking.

Despite past and pending commendable efforts to remedy the gross inequalities in educational opportunity, the goal is far from being reached. There has been a justified movement to place better schools in these areas through extending Federal support.

In view of the limited financial resources available in many rural areas, it seems clear that unless the Federal Government does extend support, the democratic ideal of equality in education will remain unrealized for rural youth.

Because inadequacies and inequalities in educational opportunity do exist, there are thousands of out-of-school rural youth poorly prepared to cope with modern life. It has been the function of the National Youth Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps to provide some education and training for this group.

These two agencies have done more than merely help the youth from underprivileged families. They have provided experience from which to project permanent policies to aid such out-of-school youth.

Unfortunately, limitation of funds has prevented them from meeting fully the needs of this mass of young people, who constitute the bulk of all rural youth and who need above all both training and guidance for occupational adjustment.

Consideration of the youth group, whether in or out of school, whether employed or unemployed, should be a definite and integral part of a program of social planning. Such a program should go hand in hand with economic planning whether under Federal, State, or local auspices.

In areas that are predominantly rural the unit for local planning is likely to be the county, though any particular type of plan that might be set up should be adapted to the particular situations of the communities concerned.

Representatives of such agencies as the extension service with its county farm and home demonstration agents; women's and business men's organizations of the villages and towns; the welfare agencies; the farmers' organizations, such as the Farm Bureau, the Grange, and the Farmers Union; the National Youth Administration; land banks; the Civilian Conservation Corps wherever possible; employment services; the schools, including particularly the county superintendent, principals, and vocational education teachers; the churches; and other special groups in particular counties that may be interested in youth's welfare could well constitute county planning councils to deal with the problems of youth.

Such councils could have at least three functions: planning for the general welfare of the youth of the county; acting as channels through which information on opportunities for work could be given to the youth of the county; and providing for adequate guidance for youth.

Such guidance involves encouraging youth to remain in school as well as helping them to make their adjustments when they leave school. The efforts of such county councils would be increased in effectiveness if coordinated and guided by State-wide councils organized on somewhat the same basis. The programs for such councils might be developed along somewhat the following lines.

In each State a division of occupational information and guidance with paid leadership and responsible financial backing could be established through the cooperation of such agencies as the State college of agriculture, the State department of education, the National Youth Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the employment services, the State department of public welfare, and other governmental and nongovernmental agencies concerned with the problems of youth. In fact, occupational information is now being gathered in many States. [Note 1]

The Rural Community Must Plan for Its Youth. Photograph by the Farm Security Administration (Lee). Rural Youth -- Their Situation and Prospects, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1531c7b80e

Through this office to the county planning councils would pass the results of the work of the many agencies that are working with youth and are assembling data on available opportunities and personal characteristics necessary for success in various occupations. With the passage of time a State agency of this type would be able through both personal representation and literature to render assistance to county councils or other county organizations that deal with youth problems.

With the available facts about occupational opportunities at hand, together with the school records and a working knowledge of the interests and aptitudes of the youth, the county planning councils would be in a position

- To help youth locate employment opportunities.

- To advise them as to whether or not they should accept some job that might be available in the community or vicinity or go to urban centers; and

- To recommend whether or not they should seek further education (with assistance from the National Youth Administration if necessary), go to a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, seek an apprenticeship in industry, take advantage of one of the training centers established by the National Youth Administration, or enroll in part-time training courses available through the schools.

Through this mechanism, moreover, the migration of youth either to cities or to other rural areas could be directed, thereby reducing the hazards of seeking to become established economically in a strange community. [Note 2]

Both the National Youth Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps have been making their programs of training more and more practical. Both agencies have demonstrated their usefulness in assisting youth to make their adjustment from the public school into an occupation. It appears essential that these agencies be allowed to plan on a more permanent basis, thereby increasing both their efficiency and their effectiveness.

In connection with advising young men about going into farming it would be well to emphasize the desirability of expanding the plan now being fostered by the Division of Vocational Agriculture of the United States Office of Education and by the Farm Credit Administration to place graduates of vocational high schools on good farms and to provide agricultural guidance until they are able to assume full responsibility for their farming operations.

By this method, the youth is given a chance to help himself and, if he is successful, in time he can purchase the farm from the Farm Credit Administration.

To the extent that rural youth can be started on good farms at the beginning of their careers they will be spared the destitution and failure that have been the lot of so many tenant, laborer, and sharecropper families.

Another educational activity which needs expansion is the discussion and evaluation of the problems of youth by the youth themselves. This i3 being done to some extent on other age levels by the forum method in both rural and urban areas.

By this means farmers themselves are planning soil conservation and crop control programs and becoming acquainted with the broad aspects of agricultural problems in America through the help of the State colleges and of the United States Department of Agriculture.

Agencies dealing with rural youth might well embark on the promotion of discussions to help the youth understand their own problems. Youth want to talk about their own problems and the problems confronting the world.

A democracy is obligated to give to its youth the facts about the complex economic and social world in which they live and which is so largely responsible for the difficulties they face in making their own adjustments.

Moreover, the solution of problems in a democracy must be a continuing process. The discussions may not produce immediate results in economic and social changes, but the conclusions reached by youth today are likely to form the groundwork for the programs of tomorrow.

THE BAFFLING ECONOMIC SITUATION

In the past rural youth entered farming or found work in a town or city as a matter of course. There was never any question on the part of themselves or their parents about opportunities being available when adulthood was reached.

If the individual wanted to work, he could find employment at home, in a city, or on new lands. The person who failed was generally considered to do so because of indolence.

"Go West, young man," was a guiding principle for decades. While agricultural areas were expanding, it was almost traditional that one son would take over the father's farm, a second go West, and a third go to the city.

During the first quarter to a third of the present century, while these traditional avenues were narrowing, education came increasingly to be looked upon as a necessary prerequisite to satisfactory adjustment into adult life.

No amount of education and training, however, will be of much benefit to youth if adequate opportunities for gainful employment are lacking. In spite of increasing pressure on the land in both good and poor farming areas many youth not needed for agricultural work have been forced to remain on farms, and many rural youth in nonfarm territory have turned to the land for a meager living.

Farm youth who are fortunate enough to be members of one- or two-child families and live on a family-sized farm largely free of debt in a good land area have the prospect of future security.

They stand a chance of coming into ownership through inheritance and of making the adjustments in their operations that may be required by developments in technology and commercial production.

Not so fortunate are youth who belong to large families, particularly in poor land areas, or who are the children of tenants, sharecroppers, and farm laborers.

More emphasis could well be placed on settling young married couples from this group, who want to go into farming, on land which will provide them a decent living and which they ultimately can expect to own or to hold under an equitable long-time lease and on giving them whatever assistance and supervision may be necessary to place their farming operations on a sound basis, instead of waiting until they have lived half or more of their lives on poor land.

Bases for programs to establish qualified youth on good land are supplied by the experience of the Farm Credit Administration and the Division of Vocational Agriculture in the plan already referred to for starting youth in agriculture, as well as by the experience of the Farm Security Administration.

The experience of the latter agency in selecting farm families in the lowest income class and supervising their agricultural activities has shown that with proper supervision and with the provision of other badly needed assistance many of these families can attain economic self-sufficiency. The youth of these families if properly taught and supervised can likewise succeed.

Unless present trends are checked and specific action taken to start youth on the road to farm ownership, more and more rural youth will never climb above the first or second rung of the agricultural ladder.

The difficulties of getting started in nonagricultural occupations also appear to be increasing. There is need of definite policies to prevent the logical consequences of these trends from blighting the lives of thousands of rural young people.

It must be remembered that probably less than one-half of the youth in agricultural territory today can be placed on good commercial farms. Consequently, the other half face one of two alternatives, accepting a lower standard of living or going into nonagricultural occupations.

This latter course involves either migrating to the cities or entering nonfarming occupations in rural territory. Such trends as increasing mechanization of agriculture, removal of sub-marginal land from cultivation, and limited foreign markets for farm products are factors restricting the opportunities for rural youth which have been discussed sufficiently (ch. II).

Introduction of new types of agricultural production and wider use of farm products already grown may offer some possibilities. For example, soybeans are being utilized for purposes other than food. Cornstalks are used in insulation and synthetic materials of many kinds.

This is all to the good. But farm products, it is well to remember, are largely consumed as food and fibers, and the expansion in consumption of both occurs very slowly. Increase in consumption depends upon an expanding population and the ability of that population to buy.

As long as population was increasing rapidly in this country through the excess of births over deaths and immigration, the increase in demand for farm products was greater than the increase in production per man.

Since population is no longer rapidly increasing, this outlet for farm products cannot be expected rapidly to augment the opportunities for commercial farming.

Owing to the fact that the solution of the problem of "surplus" youth on the land would appear to lie in the direction of expansion of opportunities in other fields than agriculture, brief consideration is given to a few possibilities.

Migration to urban centers of those not having economic opportunities in rural territory is one method of relieving the situation and preventing the increase of the lowest income group.[ ]

If it proceeds too rapidly or on too large a scale, however, migration to the cities is fraught with dangers both to the migrants and to laborers already there. Rural migrants are frequently in the position of having to accept work at any wage and under any conditions.

Untrained persons going from sub-marginal areas to the cities tend to follow unskilled occupations, and of unskilled laborers the cities already have an oversupply. These newcomers find it difficult to establish themselves while facing desperate competition in a strange environment.

Frequently these young people have no way of effectively relating themselves to other workers, to employers, and to society. [ ] Hence, thousands of young people who have sought work in urban centers within the last few years have been advised by employment agencies and employers to return to their home communities.

Directed migration could prevent in large measure the waste attendant upon unsuccessful search for urban employment and at the same time smooth the way for those who are able to enter the skilled trades, services, and professions.

It appears unlikely, however, that the cities will be able to absorb the vast numbers of rural youth who are now pressing for a start in life and who ought, under present conditions, to leave rural territory. While a limited number were being directed to satisfactory adjustments outside of rural territory, there would still be the problem of the adjustment of the remaining surplus.

Some of these should be enabled to prepare themselves for skilled trades and services so badly needed in rural communities. This should be paralleled by definite steps to make possible the utilization of these trained persons for the benefit of rural society.

It has frequently been proposed that this surplus, or part of it, might be satisfactorily provided for through part-time farming combined with employment away from the farm. The system has long been in operation in New England, and the industrial villages of the Southeast were frequently laid out on the assumption that the workers could tend small plots of land in their off-time from industrial employment.

This practice of living on the land and securing a wage from some source other than farming is common near cities and in rural industrial areas. It has several distinct advantages, such as low cost of housing, home ownership, and the production of a more adequate food supply than might be purchased, all of which supplement wages.

However, without an extension of opportunities for industrial labor with hours adapted to some work on the land, the expansion of this way of life to meet the needs of more youth appears unlikely.

Industry must evince additional signs of actual decentralization into more widely scattered areas of rural territory before this combination may be encouraged on a significant scale, except in connection with labor made available through conservation and forestry programs and such other occupations as may be developed in hitherto undeveloped rural areas.

The prospects for expansion of the principal rural industries, such as mining and small manufacturing plants, do not in general seem promising.[ ] Development of commercial services is becoming increasingly noticeable along extensions of hard surfaced highways into remote rural territory, but neither the nature nor the extent of such possibilities has as yet been accurately gauged.

While developments in scientific agriculture and mechanization of the farming process in the years to come promise to restrict even further opportunities for youth in agriculture and expansion in industrial opportunity appears problematical, the field of service occupations holds possibilities for absorbing large numbers of young people if adequate financial provision can be made for supplying more adequate social services in rural areas.

There is a distressing need for more doctors, nurses, and teachers. Society could also use more librarians, social workers, and recreational leaders. The field of personal services is only beginning to be exploited in rural areas.

In recent years, the Nation has been awakened to the consequences of unrestrained exploitation with its attendant waste of the country's natural resources. It is time society recognized the cruel exploitation and waste of its young manhood and womanhood which now exist.

The foregoing analysis may have a pessimistic outlook. The task of absorbing this surplus labor is not as easy as it might seem, nor can it be done with the facility that is implied when expansion or decentralization of industry is so glibly prescribed as the remedy for unemployment.

Talk alone does not bring about either of these developments. One prerequisite to a solution of the problem is the recognition on the part of both urban and rural society that the problem is a mutual one and that both need to appreciate the complementary relationship the other bears to the solution.

The difficulty in bringing about a full realization of the situation rests in the fact that temporary remedial measures are in danger of obscuring the long-time trends which were causal factors in the depression of the early thirties.

However, America will choose during the next few years between letting more and more of her rural youth drift into debilitating poverty and making provisions for them to travel a road to economic security.

THE SOCIAL AND RECREATIONAL SITUATION

The consequences of inequality of opportunity are nowhere more apparent than in the social and recreational life of young people. Since apparently rural youth marry at almost as great a rate in bad times as in good and in even greater proportions in the States with large destitute rural populations than in States with the higher rural incomes, it is clearly important to provide, in low as well as high income areas and in bad times as well as good, an environment conducive to wholesome family life and individual development.

It has been said that greater emphasis should be given "to values of family life, to ways of living which promote physical vigor, and to conditions which guarantee a larger measure of economic security, especially to young couples during the early reproductive years."[ ]

While education in its broader sense can do much to develop a more wholesome family life and is exceedingly important both to insure a wide selection of the marriage partner and as training for parenthood, economic security is fundamental to the promotion of family welfare.

The attainment of economic security for a substantial proportion of the families now in the marginal or sub-marginal class economically, in either rural or urban society, must occur through a process of social and economic evolution at times painfully slow.

Some of the debilitating effects of inequality of economic opportunity may be offset by more adequate provision for wholesome social and recreational life. Youth who cannot afford commercialized recreation because of their poverty may in the long run be better off if they can be guided to use their leisure time in pursuing interests that will provide a chance for full activity and self-expression.

Moreover, as already suggested, leadership in the field of wholesome recreation would afford opportunities for employment for some of the "surplus rural youth" if a program, along the lines of that now carried on by the Works Progress Administration, could be greatly expanded and placed on a more permanent basis.

Regardless of what the future holds in the way of recreation in rural areas, a fundamental question remains: To what constructive use is the leisure time of youth being put? Too often youth in rural communities are looked upon as a "floating population," meaning that they are past the age of high-school activities and have not yet reached the age for joining adult organizations.[ ]

This period in a young person's life should be bridged not only by wholesome individual activities but also by group activities that will both train and encourage him to enter into and assume responsibilities for the success of adult social-civic organizations.

Youth's participation in adult organizations outside the church is negligible if the entire bulk of the rural youth population is considered and is, moreover, definitely conditioned by social status. This, in turn, is usually conditioned by economic status.

While some of the farm organizations have made noteworthy attempts to appeal to the younger generation, they appear, with few exceptions, to have succeeded better with the juvenile age group than with youth. Moreover, they serve only a fraction of the rural population and chiefly those in the higher income brackets.

There are many factors in the situation. The fault lies not entirely with either the adults or the young people. In some cases the older generation may not take cognizance of the desire of youth to be effective participating members of local community organizations.

In other cases young people may scatter their energies over such wide areas in pursuit of commercialized urban amusements or the cheap counterpart which has invaded the countryside that there is no time or desire to join with the older folk to consider community problems or to participate in such group recreation as there may be. Roadhouses, "beer joints," and other "hangouts" in many cases provide the meeting places for the younger generation.

In some communities the tradition of what recreation should be restricts the actions of the young people with the result that they go to more distant places to do as they please. Those young people who do not have transportation facilities are then dependent upon communities that all too frequently have meager opportunities for recreation.

In those isolated rural areas where most of the families are at the poverty level, very few of the young people are able to seek diversion outside of the local community.

These are precisely the communities that have a dearth of faculties for constructive leisure-time activities with no financial resources to remedy the situation. It is not surprising therefore that in some areas of this type the principal forms of recreation indulged in by youth are drinking and fighting.

The attack on the problem of leisure-time activities cannot be uniform but must vary with the community. In some areas the first need is the provision of physical equipment, such as parks, swimming pools, tennis courts, baseball diamonds, recreational centers, and libraries.

The emergency agencies have made a beginning in this direction. Not only have they placed facilities for recreation in hundreds of communities, but they have also provided motivation for orderly behavior by providing work projects for young people.

These absorb the energy and interest of youth, and they yield a small money income. They also give youth a vision of what constructive activity can mean to the individual, and they offer the hope that life need not always be drab, monotonous, and tragic.

Local leaders in backward rural areas have many pathetic tales to tell of the hardships that some young people endure in order to be able to get to the county seat from their homes to participate in a shopwork or mechanics training project.

A major result of the work of the National Youth Administration has undoubtedly been a reduction in the volume of crime among young people. Moreover, a boy's experience in a Civilian Conservation Corps camp often does much to change his attitude toward life and to give him an appreciation of constructive recreation. This avenue of experience should certainly be kept open, and it probably should be extended to girls.

Dull and uneventful communities do not necessarily breed antisocial behavior, but they may yield lethargic and restricted personalities that are no asset to the community and that make the execution of progressive programs in any sphere of endeavor extremely difficult.

Individuals with such personalities are almost sure to lack social insight and even the elementary understanding of the workings of present social, economic, and political institutions which is so necessary as a background for a fundamental attack on local problems.

In vitalizing young people who were in imminent danger of being set in the mold of a dwarfed personality, the programs described in the preceding chapter have been of great benefit.

In rural areas that are not economically underprivileged, where there are or could be adequate recreational facilities, the approach is less obvious and may involve a change in ideology of both youth and adults.[ ]

In these areas youth must be encouraged to appreciate the wholesome value of community endeavors and neighborly fun as over against the doubtful, expensive, and ephemeral value of the mere seeking of diversion and thrills. Adults must be willing to relinquish some of their control of local affairs and accept younger people into their councils.

All this requires skillful leadership among both adults and youth, leadership which must, in large part, be consciously developed within the community, if not actually imported. In an earlier day satisfactory rural leadership may have evolved naturally. Today, however, there are too many hazards in the path of developing socially minded rural leadership to risk trusting it to spontaneous growth.

Society must, therefore, accept the responsibility not only of providing opportunity for adequate physical and mental development on the part of maturing young people but also of providing trained leadership.

Moreover, it must accept responsibility for bringing within the reach of the "other half" the means for developing rounded personalities, well equipped and eager to contribute to the life of their community.

Rural communities, and the youth who live within them, hold the power to solve their leisure-time problems. The youth themselves can do it if given direction. In addition to direction, of course, it may be necessary for help to be extended in providing facilities.

There are very few young people who would not rather engage in sports than sit around and plan mischief. The principle of keeping active young bodies engaged in wholesome physical recreation is just as applicable to maturing youth as to adolescents.

One fundamental principle to follow, however, in developing activities among youth for the wholesome use of leisure time is to give the youth themselves a chance at leadership.

Questions have been raised frequently respecting the competition of the roadhouse and other forms of commercialized amusement with community activities. Often the commercial agencies win.

It seems probable, however, that when this is the case programs have not been built with and by the youth but have been imposed by well-meaning adults." [ ]

GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSIBILITIES

The problems confronting rural youth today are the results of longtime trends as well as of the depression of the early thirties, but the depression has revealed the trends and intensified the problems.

Many long-time remedial measures must be directed at the roots of the social-economic structure of society. They should be directed in some cases to specific problem areas that cross State boundaries, in other cases to specific inequalities within local areas which need correction.

Some measures will benefit youth only through bettering the general condition; others should be promulgated expressly for youth's benefit.

Since all public services must, in the main, be paid for by taxation and since the States vary so widely in taxpaying ability, it is not to be expected that all States will be in the same position to deal with their youth problem.

Nor could the wealthier States be expected to contribute gratuitously to financing educational and welfare programs for youth in the less fortunate States merely because some of these youth may eventually become their citizens.

Hence, attempts to deal with the youth problem as a whole and to embark on a program of equalizing both social and economic opportunities, if these are to be effective, would appear to require the active participation of the Federal Government.

The Government's principal responsibilities to youth in this connection appear to fall into four categories:

- Assisting to equalize and to broaden educational opportunity.

- Helping young people find work for which they are fitted by training or aptitude.

- Providing work when private employment is not available; and (4) making provision by which youth can develop their full potentialities through wholesome leisure-time activities.

The Government has for some time past accepted limited responsibility in the first category. It has discharged this responsibility by assisting the States to bring instruction in vocational agriculture and home economics to schools serving rural areas and through the Cooperative Extension Service.

During the depression the Government has accepted additional responsibility for vocational training as well as general education for hundreds of thousands of young men from the lowest income families through the Civilian Conservation Corps camps.

Also, the National Youth Administration has extended vocational training to thousands of other young men and women from low income families by means of vocational training centers established over the country and through special training courses for rural young people at various State colleges of agriculture and other colleges.

This program, combined with the provision of student aid for students who cannot otherwise attend public schools and colleges, is evidence of the acceptance of the obligation on the part of the Federal Government to remove the economic barrier to educational opportunities, particularly on the high school level and above, for youth in low income families.

The need for these types of service has been demonstrated. Public opinion must decide how far the Federal Government should go in the future in supplementing the educational efforts of the various States. [ ]

The second and third categories of responsibility have been accepted on a broad scale only since the recent depression. Never before had the Government undertaken to provide work for its unemployed citizens or to engage in a wholesale search for employment in private enterprise for those who do not have work.

The second category of responsibility has now been accepted on a permanent basis by the expansion of the United States Employment Service of the Department of Labor and the inclusion of the work of an apprentice training committee as a regular function of the same department. Their activities should, however, be made more effective in rural communities.

Young Couple Faces an Uncertain Future. Photograph by the Farm Security Administration (Mydans). Rural Youth -- Their Situation and Prospects, Works Progress Administration, Division of Social Research, 1938. GGA Image ID # 1531e3411b

Under present conditions it appears probable that great numbers of youth—those from families above the relief level as well as those who have been the recipients of public assistance—will be unable to find satisfactory employment within a reasonable period after leaving school, particularly if they leave school at an early age.

How far the Federal Government should go in providing work and other assistance in making economic adjustments during this transition period remains to be determined. In this respect American democracy has as yet formulated no definite, inclusive policy.

Assumption of the last responsibility on a broad scale has also come since the initiation of the recreational program of the Works Progress Administration. In giving work by this means social and recreational life, much needed in times other than in a depression, has been provided in many places.

The work of this agency has pointed the way to permanent guidance and assistance for the more widespread and advantageous use of spare time by rural youth. It has no adequate program, however, to train people in underprivileged rural communities in effective utilization of such physical resources as are at hand.

It would be the better part of wisdom for America to provide an acceptable minimum of public services to these people, through Federal subsidy if no other means seems possible, to the end that a more satisfactory standard of living may be obtained.

The final outcome of the complex situation in which youth find themselves today depends upon whether definite, comprehensive, constructive policies for meeting the situation are adopted or only opportunist program building is followed. Accumulated experience points the way to enlarging and intensifying constructive action.

America has adopted a policy of conservation of natural resources; human resources are likewise in need of conservation. One step in the direction of human conservation has been taken through Social Security legislation,[ ] but on the whole it does not contribute importantly to the solution of the immediate problems of youth.[ ] Public opinion directed toward the conservation of youth must be the ultimate arbiter of governmental policy.

LOCAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Thoughtful students of rural life are constantly cautioning about the dangers of the inculcation of unhealthy dependence on Federal funds and leadership for the amelioration of the problems of rural youth. In spite of the necessity of, and the advantages to be secured through, Federal aid, the danger that many rural youth will come to feel that the Government owes them a living, that the Government is responsible for making available the facilities needed in rural areas, must be constantly guarded against.

Local groups have a tremendous responsibility in seeing that governmental assistance does not cloud the issue so far as the local situation is concerned. Many communities, though often loathe to admit it, can go a long way toward helping themselves.

The local leaders are keenly cognizant of local conditions. They should feel responsible for getting needed help for their youth and for encouraging and training them to participate constructively in community life. From this approach the values of local leadership and initiative developed over a long period cannot be overemphasized.

Only wise local leadership, moreover, can successfully incorporate into the local community life the full advantages offered by governmental agencies. Such leadership must be appreciated and retained while making available resources for carrying out programs impossible of achievement without outside financial aid.

It is easy to cite statistics concerning the accomplishments of various programs but far more difficult to evaluate their results in terms of the development of self-reliance and an appreciation of citizenship responsibilities on the part of the youth benefited.

Here is where the community faces a tremendous task in helping youth to profit most by this assistance and gradually to reach the point of relying on their unaided efforts.

Numerous local nongovernmental agencies for helping rural youth were described in the preceding chapter. Since these organizations are limited in their scope, their effects are likewise closely bounded.

However, their value as indigenous efforts to solve some of the difficulties faced by youth are incalculable and should not be overshadowed by the more extensive Federal and State programs.

With their rural leadership, with their emphasis on training children and youth for wholesome rural living and for eventual responsibility, they are deeply significant with respect to contemporary rural life.

The majority of rural youth are not touched by governmental programs, and it is on locally developed institutions that they must primarily depend.

While continuation and expansion of governmental programs for youth are earnestly to be desired, the increased development of non-governmental programs is equally as urgent.

To allow local programs to be curtailed or supplanted would bear tragic consequences in terms of the development of youth as well as of a well-rounded community life.

An equilibrium must be reached between what the community itself can and should do for its youth and the assistance it must have from outside sources.

End Notes

The National Youth Administration, for example, has already made industrial and occupational studies in Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Among the industrial studies made are those of aviation manufacturing, air transportation, baking, candy making, canning, cotton growing, furniture making, insurance, and millinery. The occupational studies include aviation, beauty culture, diesel engineering, forestry, photography, plant pathology, radio service, soil science, school teaching, and salesmanship (data secured from the Office of the National Youth Administration, Washington, D. C).

State and county councils have been organized in New York State on a voluntary basis. Efforts are now in progress to establish these councils on a legal basis. The movement is a result of cooperation between the State department of education, the State college of agriculture, and the National Youth Administration. While this plan differs in certain details from the one suggested here, the chief objectives are the same. See mimeographed statement of New York State Advisory Committee of the National Youth Administration, 30 Lodge Street, Albany, N. Y., February 11, 1938.

For a full discussion of migration see Goodrich, Carter and Others, Migration and Economic Opportunity, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1936.

4 A study in Cincinnati, Ohio, on the adjustments of migrants from the Kentucky mountains to the city showed that in comparison with residents of the same urban neighborhoods and of the same social class more highlanders worked at low-skilled occupations and more earned less than $1,000 a year. In slack times they were laid off earlier and were rehired later. See Leybourne, Grace G., "Urban Adjustments of Migrants from the Southern Appalachian Plateaus," Social Forces, Vol. 16, 1937, pp. 238-246.

See Allen, R. H., Cottrell, L. S., Jr., Troxell, W. W., Herring, Harriet L., and Edwards, A. D., Part-Time Farming in the Southeast, Research Monograph IX, Division of Social Research, Works Progress Administration, Washington, D. C, 1937; and Creamer, Daniel B., Is Industry Decentralizing! Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1935.

Lorimer, Frank and Osborn, Frederick, Dynamics of Population, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934, p. 348.

Office of Education, Young Men in Farming, Vocational Education Bulletin No. 188. U. S. Department of the Interior, 1936, p. 101.

Lindeman, Eduard C, "Youth and Leisure," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 194, November 1937, pp. 59-66, especially p. 65.

For a discussion of this point see George, William R., The Adult Minor, New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, Inc., 1937.

Unemployment compensation may be paid to young people if they have had employment of the types covered by State legislation for a specified period during the year prior to their application for benefits. Since the Social Security Act does not apply to agriculture, however, it is apparent that this legislation cannot directly affect any very large number of rural youth unless they have employment in covered industries.

Bruce L. Melvin and Elna N. Smith, "Conclusions," in Rural Youth: Their Situation and Prospects, Division of Social Research, Works Progress Administration, Research Monograph XV, Washington, DC: United States Govenment Printing Office, 1938, pp. 117-134.