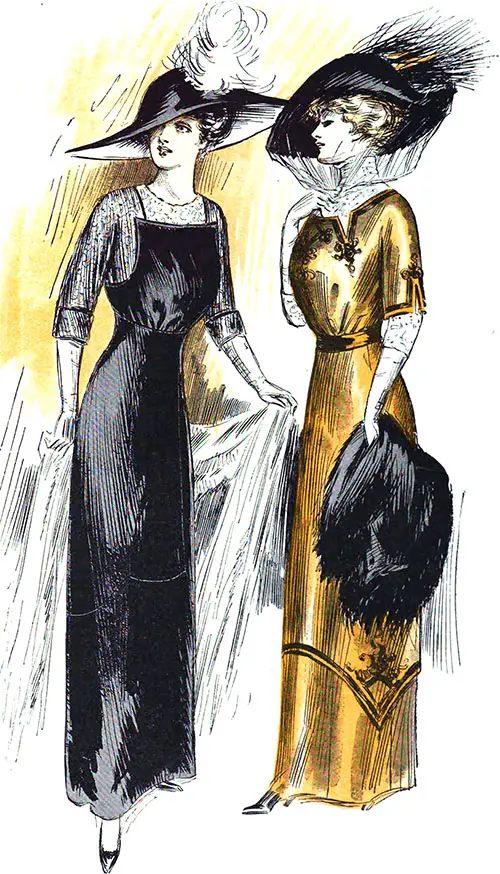

Delightful Dresses Intended for House Wear - 1911

Delighful Dresses for House Wear. The Delineator, February 1911. GGA Image ID # 164952023b

Of all ambiguous words and phrases, “house dress” seems to be the one that carries with it the most significant element of uncertainty so far as I am able to judge. Only recently a perplexed young bride wrote to me from the Middle West and asked me what she should wear for breakfast at hotels on her honeymoon.

I wrote back and told her that she might either wear the skirt of her tailored suit with shirt-waists or lingerie blouses, or a simple morning house dress. Then with a pleasing sense of having settled all her difficulties, I mailed the letter and started off for a stroll on the avenue.

Imagine my horror when I found, at the first shop I came to, a window full of kimonos and wrappers labeled with pitiless distinctness “House Dresses”! “Suppose,” I said to myself, “the little bride, like the window dresser, thinks that a kimono is a house dress!” My sickened imagination painted a dreadful picture of the poor child innocently misinterpreting my letter, and coming down to breakfast at the Annex or the New Willard in a robe de chambre. I hailed a cab and rushed back to send her a second letter by special delivery with a careful definition of my meaning of “house dress.”

To most people, I think, house gowns are any sort of negligees from Mother Hubbard wrappers to kimonos and bathrobes. But there is a much finer distinction to be drawn between them, for there are any number of indoor dresses that do not come under the head of deshabilles at all. In the first place, a house dress is a dress made primarily to be worn in the house and not on the street.

On that account, the materials used for it are generally light in weight and color—fresh prints and ginghams for morning dresses that are to be used for housework, etc.; challis and poplins for less utilitarian morning frocks; soft silks, cashmere and crêpe de Chine for afternoon house gowns. So far as their cut and fit are concerned, they are no different from other dresses.

Just the other day, a Broadway shop had a sale of little working dresses that I stopped to look at and admire, for they looked so very practical for women who potter around their own homes in the morning. They were not particularly inexpensive, for they were well made and the materials were good, but they could easily have been copied for a very small sum.

One of them that was especially pretty was made of a fine white gingham striped in two tones of lavender. It had a narrow, plain gored skirt with a panel at the front that ran up and formed the front of the tucked waist. Both the waist and skirt opened at the left side of the panel, and the waist had the new flat collar and a short sleeve that just covered the elbow. It looked very fresh and sweet and pretty—a “morning house dress” I should call it, for it was the sort of thing that one would only wear in the privacy of one's own house or flat.

Another little dress that I saw at a specialty shop farther up the avenue would have served a woman nicely for a breakfast dress if she were living at a hotel or a non-housekeeping apartment. It was made of a very soft crêpe mohair in a dull, grayish moss-green. The blouse was a simple shirt-waist laid in wide tucks at the front and set into a yoke at the back.

The shallow Dutch collar and the turned-back cuffs on the short sleeves were of white broadcloth buttonholed and embroidered in moss green. The skirt was nicely cut on rather narrow lines and with a band set just above its lower edge. Otherwise, it was quite plain, both in cut and trimming. It would have made a very nice little dress for a woman who was going to spend the Winter at Aiken or Tryon, where the mornings loaf themselves away making few demands on one's energy or wardrobe.

An afternoon house dress is quite a different creation from a morning frock. The function of the former is purely practical. You use it to save your suit skirts and nicer dresses when you do not feel lazy enough for a negligee or dressing gown. The chief purpose in life of the afternoon dress is to make itself agreeable, to look pretty and charming behind a tea-table when people whom you do not care to receive in the intimacy of your boudoir and tea gown, drop in for the cup that cheers.

I saw such a pretty dress the other day when I was making a call in Gramercy Square at a lovely old house with bright grate fires and bell-ropes that really ring bells in some distant quarter, and big mahogany doors that open into blind walls in a most disconcerting fashion when you are trying to make a graceful exit.

The dress in question was made of a clear powder-blue taffeta trimmed quite heavily with vivid scarlet. The waist had a big square collar of white satin overlaid with carmine colored chiffon, and the short kimono oversleeves ended in cuffs of the same satin and chiffon.

The collar crossed quite low on the chest, and the left side was brought across the right in a sort of attenuated revers that reached to the waistline. The collarless chemisette was cut down into a V-shaped opening in front and was made, as were the short under sleeves, of some lovely old rose-point lace.

The skirt was made with a rather long tunic that lapped at the left side of the front on a line with the closing of the sailor collar. The front edges of the tunic, instead of being straight, were cut on slightly slanting lines so that they separated toward the bottom, exposing part of the underskirt.

Both the tunic and the skirt beneath it were made of the taffeta silk, and both were perfectly plain and untrimmed save for a little braiding done in the lower corners of the tunic with a heavy cord covered with the satin and chiffon.

It was a house dress pure and simple—a dress that a woman would wear in her own home or under a carriage wrap if she were calling, but never on the street, any more than she would wear a tea-gown for tea unless she were distinctly “not at home” to the world at large. It seems a pity that tea-gowns cannot do more public service, for they are the most fascinating of all garments.

One of the prettiest of our youngest stars wears a most bewitching tea-gown in her last play. It is made of a very pale pink crêpe de Chine trimmed with quantities of Valenciennes lace.

The gown is quite loose and is drawn in at the high Empire waistline by a soft ribbon girdle caught up into a point in the back and tied in a soft knotted bow the sash ends weighted in front, with small satin buds and roses.

It opens in the front under a softly falling ruffle of the lace that runs from the flat lace trimmed collar on the tucked waist to the bottom of the flounce on the skirt. The flounce has a single deep tuck near the bottom that gives some weight to the light, flimsy material.

In another scene in the same play, this very deshabille heroine wears a most charming little bed-jacket or liseuse, as the Frenchwoman calls the little coatee that she slips on over her nightgown when she reads in bed.

This particular liseuse is made of cream-colored net mounted on pale blue satin and trimmed with narrow ruffles of cream-colored lace. The upper part of the jacket is laid in a cluster of tucks near the shoulder, and the lower part is finished with a belt and peplum.

Helen Berkeley-Loyd, "Delightful Dresses Intended for House and All Hours of the Day, " in The Delineator, New York: The Butterick Publishing Company, Vol. LXXVII, No. 2, February 1911, pp. 101-103.