King George V and the Great War - 1920

King George V in Uniform circa 1920. GGA Image ID # 1872322be4

Chief Dates

- 1910. Accession of George V; Second General Election of 1910.

- 1911. The Parliament Act. National Insurance Act.

- 1912. The Balkan League.

- 1914. Home Rule and Welsh Disestablishment Bills become law. Outbreak of war with Germany. Battles of the Marne, Aisne, and Ypres.

- 1915. Second Battle of Ypres. The Dardanelles Expedition. Battle of the Dunajec. The Asquith National Ministry.

- 1916. Capitulation of Kut-el- Amara . Battle off Jutland. The Dublin Rebellion . The Lloyd George Coalition Ministry.

- 1917. Capture of Bagdad. Battle of Caporetto. America at war with Germany.

- 1918. Treaty of Brest-Litovsk . Failure of German offensive in France. Second Battle of the Marne. Conquest of Syria, Mesopotamia, and Serbia. Armistice signed. Reform and Education Acts. General Election.

George V and the House of Windsor

George V was forty-five years old when he became king. A second son, he was an active naval officer until his brother's death in 1892 put him in the direct line of succession. He was known as a good sailor, a great traveler, and an excellent speaker.

He threw himself conscientiously into the discharge of his position's delicate duties and showed courage in speaking his mind. In 1893 he married his second cousin, Princess Mary of Teck, a great-granddaughter of George III.

Though the daughter of a German father, she was born and brought up in England. Thus, for the first time since the Tudors, both king and queen were thoroughly British in sympathy and education.

This was emphasized after the German war outbreak, when king George repudiated all foreign titles and desired that his dynasty should be known as the House of Windsor.

The Crown, The Dominions, and India

The new king appreciated the importance of the crown as a link between the various portions of the Empire, which were tending to drift in different directions as they severally worked on their own destinies.

His uncle, the Duke of Connaught, who had already been sent to South Africa to open the first Union Parliament, was appointed Governor-General of the Dominion of Canada.

In the winter of 1911-1912, the king and queen went to India, being the first British reigning- sovereigns to visit the greatest of their dominions.

They held a magnificent Durbar in Delhi. The king announced the transference of India's seat of government from Calcutta to Delhi, the old capital of the Mogul Empire.

Many schemes for the improvement of the government and the development of the resources of India were suggested, and in 1917 a considerable advance in the direction of Indian self-government was promised.

During four years of war, the loyalty of India and the large share taken by Indian troops in the campaigns gave reasons for making such changes as early as practicable.

Meanwhile, the self-governing colonies were all developing their own resources. Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa set an example to the mother country by schemes for organizing national defense The problems of the relations of the Dominions to the Empire, though much discussed, were never seriously faced.

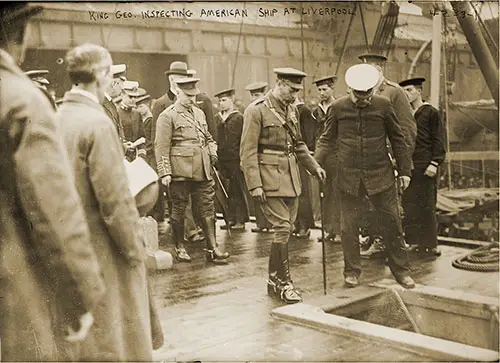

American Sailors Saluting King George V of Great Britain during His Visit to Their Troop Transport Ship the USS Finland, Docked at Liverpool, England, 1917. Photograph by Bain News Service. Library of Congress LC 2014704814. GGA Image ID # 18724b2846

1910-1914

The Second Election of 1910

Between 1910-1914 Parliament was hotly engaged in the old party warfare, though it found some leisure to deal with problems more deeply affecting the heart of society. The great fact for the politicians was the impending conflict between Lords and Commons.

To avoid this, an attempt was made to bring about an understanding between the two houses by a conference of party leaders of both sides. On the failure of the effort, the government appealed to the country, seeking a clear mandate from the electors to destroy the House of Lords' veto.

The Parliament, elected in January 1910, was dissolved in November, and another general election was held in December; but the balance of parties in the new house was the same as in the old one.

The number of Liberal and Unionist members was exactly equal, so that the ministry, as in the earlier Parliament, could maintain its majority only when it could secure Irish Nationalist and Labor support. It was accordingly with weakened authority that it began in 1911 to put its proposals into practice.

The Veto Act, 1911

A Parliament Bill was laid before the Commons in February 1911. The Lords' absolute power to stop all legislation was to be changed into a suspensory veto.

The Lords were neither to reject nor amend a money bill; any other bill, if passed by the Commons in three consecutive sessions, was to become law, irrespective of the action of the Lords; the duration of a Parliament was to be cut down from seven years to five, so that only measures passed by a young House of Commons could be pushed through, over the heads of the Lords, without an appeal to the people.

To meet complaints that no proposals were made as to the reconstitution of the upper chamber, the Prime Minister pledged the government to bring forward a scheme for this within the lifetime of Parliament. However, insisting that the Parliament Bill must be got through as a first step, he carried it in the Commons.

The Lords' attempts to amend the bill were firmly resisted, and as the Lords dared not persist, it became law by August. A measure was also carried to pay each member of the House of Commons £400 a year for his services. Other government measures, including the budget, had to be postponed to an autumn session.

National Insurance Act, 1911

In this autumn session, Lloyd George finally passed his National Insurance scheme. This plan secured that all workers with an income below a certain level should be provided with an allowance, in the event of their sickness or unemployment, out of funds to which the insured person, his employer, and the State alike contributed.

This was the first of a series of measures designed to make life more tolerable to the mass of the population and to mitigate the harshness of the industrial struggle for existence. Unrest, culminating in a series of strikes, showed that there was widespread dissatisfaction with existing conditions. The most serious of the labor troubles was a great strike of colliers in the spring of 1912.

Home Rule, Welsh Disestablishment, and Parliamentary Reform, 1912

In 1912 also, Parliament sat most of the year. The government proposed setting up the Home Rule for Ireland, to disestablish and disendow the Welsh Church, and to widen the electoral franchise. Its Irish scheme took a different shape from the provisions of the Home Rule bills of 1886 and 1893.

Ireland was to have a parliament of two chambers, a House of Commons, and a small, nominated senate: but the Irish Parliament was only gradually to take over its full powers, and was not to make laws concerning the crown, the army, and navy, or foreign policy.

There was also to be an Irish executive, responsible to the local Parliament. Forty-two Irish members were still to sit at Westminster, with powers equal to those of Great Britain's representatives.

The bill produced acrimonious debates, and the Irish Unionist members, led by Sir Edward Carson, openly threatened resistance in its becoming law. However, the measure was slowly pushed through the Commons, only to be rejected by the Lords.

The Welsh Church Bill, also passed by the Commons, had the same fate. The New Reform Bill proposed that no man should have more than one vote that residence or occupation should be the sole qualification of a voter, and that the cumbrous registration law should be simplified.

However, there was no proposal to rearrange the constituencies or give women votes, despite strong agitation, both inside and outside Parliament, in favor of the later step.

An amendment for giving women votes was ruled inadmissible by the Speaker. Thereupon Asquith withdrew the whole bill. He promised to give facilities next year for the discussion of a measure for women's suffrage.

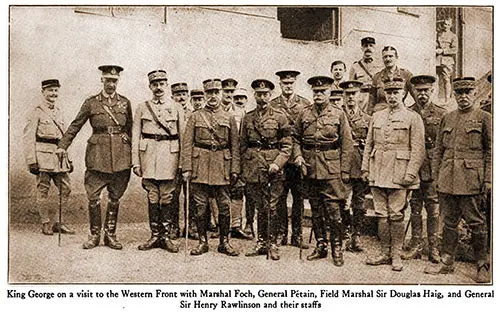

King George on a Visit to the Western Front With Marshal Foch, General Pétain, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, and General Sir Henry Rawlinson and Their Staffs. A Remarkable Group of British and French Leaders Photographed on the British Front in 1918. King George Is the Center. at the King’s Right (Left of Picture) Are Maréchal Foch, General Debeney, and General Rawlinson. at the King’s Left (Right of Picture) Are Field Marshal Haig, General Petain, and General Fayolle. British Official Photo. The United States in the Great War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18725773fc

The Session of 1913

Unfruitful debates prolonged the 1912 session till February 1913, and, after a few days' intervals, the new session began. The Home Rule and the Welsh Church bills were again sent up by the Commons and again rejected by the Lords.

The same fate overtook a bill abolishing plural voting while leaving untouched the electoral system's other anomalies. A "Women's Suffrage” bill, brought forward by private members, failed to pass the Commons, the Prime Minister, being in the forefront of the opposition to it.

Ulster and Home Rule, 1913-1914

The government had not improved its position either in Parliament or in the country. Even its more broadly conceived measures, such as the Insurance Act, were difficult to carry out and required amending and supplementing before they worked well.

The Prime Minister was vigorously attacked by the friends of Women's Suffrage, who thought that he had interpreted his pledge in too lawyer-like a fashion. Adverse goodbye-elections slowly undermined the Liberal majority and increased the ministers' reluctance to appeal to the country.

The worst trouble before them seemed to be the disturbed State of Ireland, brought about by the fact that the Home Rule Bill would automatically become law by the end of the session under the Parliament Act.

Headed by Carson, the Ulster Protestant party took a solemn covenant to resist Home Rule by force. It drilled and armed a large force of Ulster Volunteers to defend Protestant Ulster. The Nationalists naturally followed the example and levied a host of National Volunteers to enforce Home Rule.

Ireland was divided into two armed camps, each professing to prepare to fight the other. The Irish government, barely controlled by the weak Irish Secretary, proved incompetent to either comprehend or restrain the fierce passions that its proposals had excited.

Home Rule and the Ulster Covenant 1914

In this tense atmosphere, the session of 1914 opened. The government once more brought forward its old measures, but, as a concession to Ulster, it allowed any county, or county borough, to exclude itself by popular vote from the Home Rule Act for six years.

Carson offered to consider permanent exclusion, but ministers refused to move any farther. Rumors spread of a projected concentration of troops to enforce Home Rule on Ulster. Thereupon some highly placed army officers stationed in Ireland sent in their resignation.

The result was a ministerial crisis, involving the resignation of the minister of war and of Sir John French, chief of the staff. The trouble was patched up only by the Prime Minister himself undertaking the charge of the War Office.

Nevertheless, the Home Rule Bill was still pressed through the House, Asquith maintaining that concession to Ulster must take the shape of a subsequent amending act. But his Amending Bill was only produced because the Lords refused to discuss the Home Rule Bill until this was done.

It proved to be the old offer of six years' exclusion to any counties voting for such a course. The Lords then amended the Home Rule Bill before them by excluding all-Ulster from its operation.

The danger of war with Germany led the king to summon a conference of all parties to Buckingham Palace, but nothing resulted from this. After war broke out, the Government dropped the Amending Bill and forced the Lords to reject the Home Rule Bill.

When the Welsh Church Bill was again sent up to the Lords, it was once more thrown out. As union against the German peril made it undesirable that these two fiercely opposed measures should become law at the end of the session under the Parliament Act, a Suspensory Act postponed their operation until after the war.

Thomas Frederick Tout, "Chapter II: George V. and the Great War (1910-1918)," in An Advanced History of Great Britain from the Earliest Times, New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1920, pp. 740-744.