Where Bad Citizens Are Made - 1921

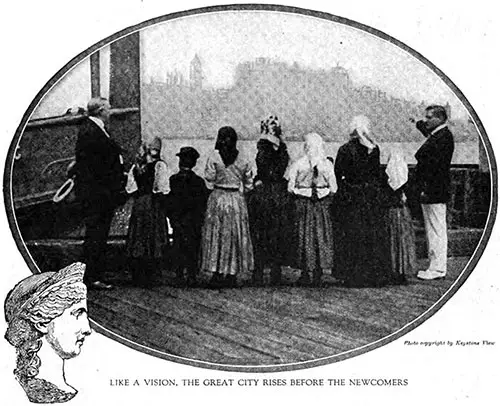

Like a Vision, The Great City Rises Before the Newcomers. Photograph by Keystone View Co.The Delineator, March 1921. GGA Image ID # 14d1ba127d

Wouldn't You Hate America If It Met You This Way?

By Marie de Montalvo and Rose Falls Bres

Read this story of what women and children endure at Ellis Island, where many immigrants gel their first taste of America. Then, while you are still boiling with the sense of injustice and outraged decency, write your congressman that conditions must be changed.

Talk about the cause of these immigrant women and children in your church. It will not stand for this gross violation of Christian principles. Talk about it in your club. The hatred that Ellis Island breeds is spreading like a plague to increase the discontent which menaces our institutions and the Government itself.

Do you know what happens at Ellis Island, in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, to the women who come to America from other lands because they think that this is the land of freedom, of justice and of plenty—women whose only crime is poverty, whose only offense is ignorance of our language and our ways?

Never mind the millions of men who are pouring into, this country, and the millions more who are waiting over there to come, some with passports, waiting for a few inches of space on some America-bound ship, and millions more still waiting for passports.

They constitute a problem of enormous importance—but we can leave it to the men. The thing that concerns the women of this country is that the proportion of women coming to this country is increasing, and nothing is being done about it.

National and international problems are coming to the point of confusion and complexity, which makes us feel that a man who seems to know what he thinks must be mistaken.

Immigration is one of the complicated problems about which people think and feel, and hardly anyone knows anything. Yet it may be possible to make one assertion which we can all agree to.

There are just two things to do with the immigrant to keep him out or treat him fairly.

Now, women of America! Do you know that women surrounded with children, carrying small babies, squeezed into airless rooms among men, are forced to stand day after day and week after week waiting for a man with a megaphone to yell their unpronounceable names at them so that they may know their relatives have come for them?

Do you know that after they disembark at Ellis Island, they are pushed and jostled and shouted at and bullied by so-called "officials" whose qualification for the job seems invariable to have been a harsh voice and a hot temper?

Do you know that women with babies and baggage are forced to stand in line for at least half a day, and sometimes several days, and negotiate several flights of stairs, carrying with them everything they own on earth before they pass their physical examinations, which could all be performed much more quickly and effectively on the same floor?

Do you know that there are 2,089 bunks on Ellis Island, provided with two blankets apiece; that because detained immigrants must be segregated into classes, only 1,500 of these beds are available—since if there are only ten Chinese, and the dormitory for Chinese holds twenty-five, the remaining fifteen bunks must remain empty rather than fill them with white people—and that recently on the Jewish holiday, Yom Kippur, 3,500 people remained five days in Ellis Island, of whom 2,000 men, women and children were without bunks and had to lie on the floor or sit up all night, six squeezed together on each bench?

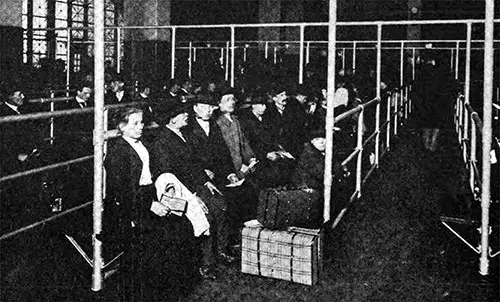

2,000 Men, Women, and Children Remained for Five Days at Ellis Island Recently, Without Bunk Beds, and Had to Lie on the Floor or Sit Up All Night, With Six Squeed Together on Each Bench. Photo © Brown Bros. The Delineator, March 1921. GGA Image ID # 14d1d00671

Do you know that there is no place for women to wash themselves, their clothes, and their babies, except at a sink out in the public hall? And no place to dry their clothes except on lines strung over their bunks in unventilated dormitories, with bunk beds four deep up and down the walls, where they must remain anywhere from a single night to a year?

Can you imagine the mental attitude of government employees who stopped up the faucets in the eating halls because they might drip on the floors if immigrants were allowed to drink water with their meals?

Have you a picture of a baby whose underclothing remains unchanged for so long that its skin peels off with its garments when they are finally removed?

Do you know the inadequacy of the sanitary arrangements—such that a visitor hates to inspect them because their awful presence is made known long before they are visible to the eye?

In brief, do you smell Ellis Island when you read these words?

When United States Commissioner of Immigration Frederick A. Wallis first went to Ellis Island, he noticed the women holding babies in their arms, who must stand in line for a day, sometimes, waiting their turn to pass.

It was trying and tiring and sickening enough for strong men who were not so burdened to drag their luggage up and down the interminable flights of stairs, then stand and wait for hours. Think of what it meant to the mother of eight little children, one of them in arms, with eleven pieces of baggage!

"Women with children first," was the first rule laid down by Commissioner Frederick A. Wallis. It seems as if some other commissioner might have thought of that years and years ago. Surely if there had been a woman at Ellis Island, she would have thought of it very quickly.

Next, he saw the crying children. And one of the terrible things about Ellis Island is that you can't ask people why they cry. If you ask, they cannot tell you. You must go and hunt up someone, perhaps a long way off, to find out for you. After you've been there half an hour, you'd rather know another language than own a million dollars.

The children cried, the commissioner found out, because the milk was sour. If it wasn't sour, it was always cold.

Any woman would have known long ago, at Ellis Island, that cold milk makes little babies ill. It is nothing against former commissioners that they didn't know. Men just don't seem to find out those things. Mr. Wallis did, and from the time that he first went there warm, fresh milk has been served to mothers and their babies at intervals during the day.

The newly appointed commissioner noticed next that these poor creatures slept with their clothes on, and asked the social workers to "teach them how to go to bed." Then he inquired what had become of all the towels.

Towels! The employees of the Island threw up their hands in wonder. What sort of man had been sent to them in authority? Towels for immigrants! What had immigrants ever done to deserve them? Very likely, they had never had towels where they came from. Why should they have them here?

They had no information on the subject of towels, and so stated to the commissioner. After which, the commissioner looked again at a particular inventory, noted the plain statement of a stock of thirty-odd thousand towels, brought them forth, and now immigrants are using towels.

And these same employees at Ellis Island-have you seen how they talk to the immigrant women? Have you been there, in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, and wondered whether a harsh voice, a rough hand, and a hot temper were the only qualifications necessary to get a job welcoming strangers to our fair land?

"Get back! Get along there! Quit that! Here, you get a move on! Hey, you, Ivan Ivanovitch, get out of there! Come here! What are you waiting for, you, Olga? Can't you hear? Are you deaf? No, I won't listen to you, come out of that-"

The tone is mightily like that of "Gee!" and "Haw!" when oxen are being driven, and the scene is a roped enclosure holding several hundred human beings back from a door just outside which. Just out of their longing sight, relatives are waiting, day after day and week after week, to claim their immigrant kin.

A man stands on a bench in that great crowded room shouting names through a megaphone-long, twisted, often incomprehensible name. And toward him on all sides in the crowded room are turned faces—the faces of children, white or brown, or glowing with the last fires kindled by the sunshine of a recent voyage; faces with delicate, hollow cheeks and high cheek-bones from Czechoslovakia, with the vivid, proud beauty of Sicilians, or silvery Scandinavian blondness—but all of them anxious faces. For upon the calling of a single name depends on the fate of families who come in through Ellis Island.

That delicate face under the Paisley-patterned headdress—it had been inclined to the man with the megaphone every day now for three weeks, while shadows darkened around its wistful eyes, only adding to their beauty.

The little girl from Czechoslovakia—she may have been fifteen—had shown real courage. But today it had reached its climax, and she pulled down the Paisley headdress to hide her tears.

The visitor to Ellis Island lost all her manners and pulled the sleeve of the director of social service. "That girl there"—she made herself heard through the babel of foreign languages— "couldn't you find out why she is so worried?"

Of course, it was against all the rules, but those who deal with the humanities, and that means, most often, women, find it their chief duty to see that all rules are broken once in a while. So a slip of a girl from Czechoslovakia found an arm about her, and she was led away from the crowded room to talk to an interpreter.

Nothing much was wrong. That was the pity of it. The girl had come with a cousin, and the cousin had a

child. That made a different kind of a "case," and she and her child had been sent away up-stairs while the others remained below. But the girl in the Paisley headdress knew only that the only creature she knew and was able to speak to in this strange, new land had been taken away from her, and she thought perhaps she might never see her again. This she explained to the interpreter, while swift eager smiles at being able to talk and be understood broke through her despair.

"Take her up-stairs," said the director of social service, "and see to it that she finds her cousin and talks to her if it's only for two minutes."

And a radiance like sunshine lighted the shadowed, anxious face under the Paisley headdress.

Here in this place, startlingly like the pens and runways of a slaughter-house for cattle, not long ago a woman waited, sickening in the foul air, weary of standing where there are no seats, frightened into despair because her child was ill and had been taken from her, terrified because her husband had not come for her.

More than a week, she waited—and all the time, her husband, not five feet away, out of sight behind the next partition, was waiting too, sick with anxiety—because the man with the megaphone had been unable to pronounce their name.

Ivan and Olga are youths of fourteen and a woman of twice that age, and each carries heavy bundles tight-packed with their worldly goods and chattels.

The woman is in dingy black, and the boy has a string of black for a tie. The relative who waits for them—undoubtedly the brother of the woman, from the resemblance of feature and expression—has a mourning-band on his cheap hat. It does not take a vivid imagination to piece out the story of a war widow and her son, and their search for a home in the new land.

They are both gathered after many days in the arms of the waiting relative, and the sobs and kisses of their relief bring a lump into the throat of the visitor-until America, in the form of a bully, shoves them apart with rough hands and not a little help from his ready, rough-shod foot, and again comes the greeting of America: "Get along there! Whaddya mean, blocking the passage? Out of the way! Move on! Get out!"

Immigrants in the Maze at Ellis Island, Waiting to be Inspected. "The Stream has become a Flood. There are War Widows, Many of Them; There are the Women Left Destitute of Funds by the War, Coming Here 'On Their Own' to Earn a Living." Photo © Brown Bros. The Delineator, March 1921. GGA Image ID # 14d2a09531

It is a scene enacted once a minute under the signs upon the wall labeled in large type "Treatment of Immigrants" and containing in plain English half a dozen excellent commands to be kind.

You ask, then, why this brutal rounding-up is tolerated? The answer is equally brutal, but it is true. Rough tones and shoves from ungentle hands are the only language the immigrant understands.

These strangers are from every land under the sun. America can not furnish an army of attendants, such that a Russian may call for the Ivanovitch family and take them to where they may talk and kiss to their hearts' content.

A Dutchman do the same for the little Dutch family, an Italian for the Italians, and so on; but unfortunately there is a tone which in any language means to go when you are bidden and come in haste when you are called, and that is the tone, aided by the foot and hand, which is used to immigrants.

And this brings us back to the original premise: We should either treat them right or keep them out. The saddest thing on the face of the earth is the sight of a woman with a baby in her arms being roughly driven, and the knowledge that, as conditions are now, anything else is impossible.

Women of America, you have a duty toward your immigrant sister: Either see to it that these conditions change, or that she does not come here.

If the stream of incoming women were a thin one, the welfare-workers, of whom Col. Bostedo is head, could help and ease their lot.

But the stream has become a flood. There are war widows, many of them; there are the women left destitute of funds by the war, coming here "on their own" to earn a living; there are the women relatives of men already here who earned enough during the war to bring their families over now.

There are pitiful groups of refugees from Bolshevism who have seen their menfolk slaughtered and tortured before their eyes, their children die of hunger, and a future of nameless horrors stretching out before themselves.

And the whole forms a torrent sweeping toward America by the million, enough holding passports in their hands right now to crowd every incoming ship for the next five years. The only thing that can be done for these foreign women is for the women of America to constitute themselves each a unit in the army of home defense.

Figures show that far the more significant part of our population is born of immigrant women, and thus that the future of America is in their toil-worn hands, their anxious hearts, their ignorant, uneducated minds. And so they constitute a problem which, notwithstanding their soft eyes, their tears and their humility, may threaten the very foundation of American institutions.

EVERY time a woman suffers excessive hardship en route from debarkation to somewhere in America, there is nourished in the bosom of the land an enemy—and difficulty for those passing through in such unpremeditated numbers is inevitable.

But conditions incident to such overcrowding is the sort that women know more about than men do, for they are the problems of housekeeping on a large scale.

No woman who has ever arranged a slide through which to pass hot soup from the kitchen to the pantry instead of carrying it around through the door would tolerate for one moment the fact that three medical examinations are made at Ellis Island on different floors when they might be done on the same floor.

No woman would submit her family to the condition which permits immigrants to be detained in a room that holds eight hundred people and contains six benches, each one big enough for three.

No woman exists but, given the power, would devise some way for an immigrant to buy, even with foreign money, a two-cent stamp to write to his relatives the first day after landing, instead of the last day before he is released, when all his money is changed.

Of course, there are inevitable hardships.

We cannot have suites deluxe reserved at our leading hotels for incoming immigrant women and their children. A perfect world is not expected by the quite sane, and it is only poets, sentimentalists, and Bolshevists who preach the doctrine of freedom from all restraint, wealth without work, and elastic civic conditions to meet any need.

But many that we have noted are hardships which we should avoid if we are to let the immigrants come at all, or we will suffer in the end as a nation much more than the immigrant does as an individual.

The searchlight of inquiry turned upon male aliens at ports of entry discovers a startling number equipped with blackjacks and black intentions. These men, if they do not have them written on their faces, carry evidence of criminal bent in their pockets.

But women over there, no less than here at home, have found that their sphere need not be bounded by kitchen stoves and washtubs. They have taken a hand in things in Europe. They have actually fought in the trenches. They have led mobs. They have organized revolutions.

And some few there may be of these who hide with humility and tears their active, red thinking minds, if not a knife in the sleeve.

Along with inquiries about foodstuffs, new fashions in local laws, and club activities, it might be just as well for American women to get acquainted with their sisters traveling third-class from abroad. Inevitably American women can cross wits with the women from any land and win.

Perhaps the need to do so is at the very gates of America in the tide pressing there for admission. Mostly the foreign woman's unlawful bent lies in her ignorance. She does not understand, and incidents that may start her on the wrong track can be seen by the dozen at Ellis Island.

Newly Arrived Immigrants from the Third Class. "It Might Be Just as Well for American Women to Get Acquinted with Their Sisters Traveling Thrid-Class from Abroad." Photo © Brown Bros. The Delineator, March 1921. GGA Image ID # 14d20dc761

Note the case of the woman who came over with four children, of whom one on the day of arrival came down with scarlet fever. It was taken from her to the hospital, and, obviously, she could not be allowed to see it.

The next day another child was stricken and removed from her, and on the following a third—and all three died. And when the last one sickened and an attendant came for it, she screamed and fought, crying: "Don't take this one away and kill it too!"

In time, that woman will pass into America's melting-pot, her heart and brain seared with grief and desolated with the loss of her children. She will go her way among other foreign women believing her children have been killed and telling others so.

Sullen, pressed down by poverty, she will sow discontent from the time of her landing and will be forever an unreconstructed rebel, unless American women help her. And it isn't flights of oratory in lady-made speeches that are needed.

Foreign women are hard to get to, harder to "get next" to, hardest to lead from native customs and loyalty to friendly fellowship with American institutions—but there is a language among women which only women understand, and it is universal.

Only women can explain to the newcomers why this or that condition may be almost intolerable but cannot be helped without time and legislation, and that no oppression is meant to strangers by it.

And women must be there to explain, for even without hardship to endure, the immigrant is homesick. With many miles between, the miseries at home seamless, the old country looks rosy far away, and little Giovanni and Heinrich and Pat and Olga and Sonia will imbibe with their mothers' milk a warmed-over loyalty to foreign lands, and a new, hot hatred for this one.

Immigrant women will be mothers of Americans. What should we do with them?

Marie de Montalvo and Rose Falls Bres, "Where Bad Citizens Are Made," in The Delineator, New York: The Butterick Publishing Co., Vol. XCVII, No. 2, March 1921, pp. 8-9, 54, & 57.