The Loves of Ellis Island - 1909

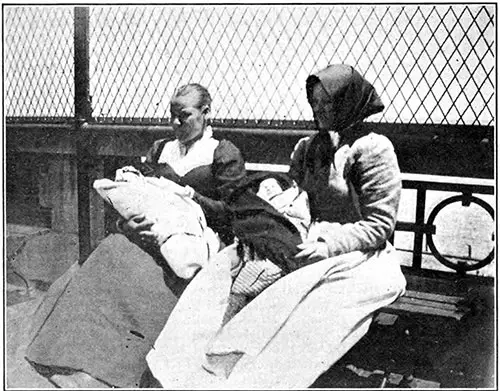

Two Young Dutch Mothers, Their Babies in Swaddling Clothes, On the Roof of Ellis Island. Home Mission Monthly, August 1901. GGA Image ID # 14f7c27a80

In This Flood-Tide of Foreign Humanity One May Discover the Real Pulsing Motif that Throbs through Human Life

By MABEL POTTER DAGGETT

GREAT artists have tried to paint it. Great poets have sung it. At the Place of Tears and Kisses you may see it, the real pulsing motif that throbs through human life. A gong has sounded twice.

There is a tremulous movement of the American flag suspended across the great hall. Now beneath its folds a long line is struggling up from the sea and the steerage.

It is another shipload seeking admission to the American shore. At this threshold of the continent out in New York Bay they pass in review. Government inspectors look them over to see if they are fit.

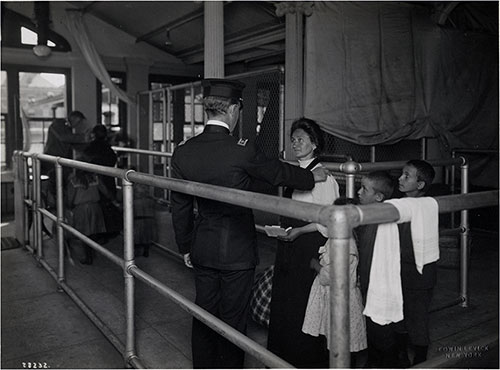

Immigrants Undergo Medical Examination at Ellis Island ca. 1908 (1902-1913). Photograph by Edwin Levick from the William Williams Collection. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, New York Public Library. NYPL # 416754. GGA Image ID # 14ea9ea1e3

Here and there where a white towel hangs on the wall, doctors examine eyes or tongue, and wipe their fingers for the next. Down at the end of the row they must give their personal history. Are they anarchist, pauper or criminal? No.

Then a small iron gate swings easily outward. The inspection proceeds without protest. Not in a day or a generation did these people learn their respect for authority. They know a brass badge when they see it. They are coming along in droves.

Almost akin to dumb driven beasts they seem to you looking down from the visitors' gallery. Many are small and stunted. Mostly their lives have been spent in the bearing of burdens. In the furrowed faces are written hardship and toil.

But wait. In their hearts is something more. Beneath a peasant's coat you may find the same divine spark that links you to immortality.

When the immigrant has lifted his eyes in hope toward his promised land of better fortune, there has been that which has made the pursuing of fortune worthwhile.

Lacking it, men and women of many more material possessions than the bundle slung over yonder traveler's shoulder have asked of the universe a “why” that has echoed back from an empty void.

In the Loves of Ellis Island you may find a theme to answer the eternal question of existence. You shall see the immigrants laugh and cry. Nothing more matters much.

After many winding passageways they have come to the department marked by the sign on the wall the “Discharging Division.” No name, that, for a place where the greatest wonder of the world flashes forth before your eyes. One would speak here only words that are soft and sweet.

There is a stone floor, tall windows admitting a gray light, and a long desk at which sit inspectors on high stools. Behind in a compartment partitioned off with latticed wire are immigrants passed as satisfactory for admission to the United States. They are waiting to be called for.

Their friends come by the ferry-boat from the Battery. It has just arrived outside with an eager throng. On the way Over, utter strangers smiled into each other's faces and in many alien accents spoke together a common joy.

“Since last night when I got the telegram, it has seemed also like a year that I have waited.” “You have never come for any one before?

I have taken out already five, and I will show you where to go.” “My breakfast I could not eat at all. I was so glad.” “Not in seven years have I seen her, but I shall know her! I shall know her!”

So, talking excitedly they reach the gray lighted room. They move in line before the high desk to make application each for his own. As they enter, the latticed cage beyond thrills with anticipation. The folk song of a far homeland crooning in a corner hushes Inspectors look them over quietly.

A child crying stops suddenly to find out what is stirring its elders. The people crowd toward the latticework. They press their faces close to peer through. Outside, just beyond reach, are dear ones whom the years and the ocean have rolled between.

As they recognize relatives there is an exclamation, a cry in a foreign tongue. They gesticulate. They call across the intervening space. They throw up hats. They wave handkerchiefs. And the line beyond, in more subdued agitation, waves back.

The door is locked. It has to be. In their impatience, some even now are shaking the wire lattice. Some lean against it, their heads bowed on their arms in tears. Meantime the red tape of the Discharging Division of the Immigration Service of the United States Department of Commerce and Labor measures off slowly, surely,

No money, no friends, she will have to return safely. These new arrivals the Government holds in its keeping. Before surrendering them, particularly women and children, it must be sure of their destination. Uncle Sam does not mean to let girls go wrong.

Those who say they are relatives must prove it. “What is this woman to you?” is searchingly asked. And the answers to all questions of family history must tally with the information on the immigrant's landing-card.

Satisfied that all is well, the inspector gets down from his stool and turns the lock in the latticed door. We may see with him the simple life and the warm heart of it.

“Katrina Wurtemberger,” he calls. A smiling woman in a woolen dress and heavy shoes pushes past the rest, a brood of nine about her, little girls with plaid dresses and tightly braided yellow hair, little boys in long trousers and queer caps.

The man who has rushed toward them is a homesteader from the Canadian Northwest, his honest German face aglow with joy at claiming his own. At the pillar which all Ellis Island calls the “Kissing Post” they meet.

He gathers them to his heart, reaching out after the mother and all the rest his arms can hold. “Meine liebchen, meine liebchen,” he says over and over. And he hugs them together, and he hugs them separately until an attendant good naturedly admonishes, “Move on.”

The door has clicked several times. More are coming toward the Kissing Post. Bridget Muldoon in a black shawl and a gingham apron lays her old head on her daughter's shoulder. And the daughter, fashionably attired, a buyer for a New York department store, holds the shawled figure close and kisses the wrinkled face tenderly.

Simon Kapoletsky drops a huge bundle on the floor to throw his arms about a young man from the East Side. They embrace again and again, as the old man murmurs brokenly in Yiddish, “My boy, my boy!”

Zofia Kaceluk's kerchiefed head is bowed low as she frantically kisses the hand that would draw her closer.

“Is this your sister?” the inspector had asked her. And poor Zofia hardly knew, for her wonder of this fine grand young lady Joseffa has become, wearing kid gloves and a hat with a soft feather. Joseffa, who sent the money for her passage, has been here two years.

She works as a domestic and earns twenty-five dollars a month. As they go out through the door labeled “New York” she unties the paper parcel that she carries. Before they reach the ferry-boat, Zofia's peasant head-dress will have disappeared and she will be wearing uneasily but proudly her first hat. No street gamin of the metropolis shall call “greeney” after Joseffa's sister.

Terezia Petrona, whose aunt has asked for her, is not getting through easily. She is sixteen and too pretty.

Accompanying the aunt is a young man who telegraphs, right over the inspector's head, ardent glances that Terezia knows how to answer. “I don't like the fellow's looks,” objects the inspector. “How do I know what he wants of the girl?”

Her aunt is protesting in distress, and behind the lattice Terezia's dark eyes are suffused with tears. Up comes the chief inspector with gray-haired wisdom. “Tut, tut!” he says to the careful younger man. “Have a little faith in human nature. Suppose the boy is her sweetheart. That's no crime. Let the girl go.”

“On your responsibility then, sir,” answers the other disapprovingly. Terezia flies to her aunt's arms. The young man looks on hungrily. To him she shyly gives her hand. Then she stoops for her bundle. She brought it up from the ship balanced gracefully on her head.

With an exclamation he reaches beyond her. He is good-looking and well-dressed. In their country, men do not carry women's burdens.

The bundle is large and blue. But he picks it up and leads the way to New York. It is all right. He certainly loves her.

In the latticed waiting-room another pair of lovers talk. She is ticketed “to her intended husband.” They have let him through to see her. And now she hesitates. She has changed her mind. But Jan paid her passage over from Hungary, where they grew up together.

He holds her hand and talks eagerly. She stares at the wall. She drops her eyes and lifts them coquettishly. Now she shakes her head. “What are they saying?” I ask an interpreter. “Oh,” he tells me, “the boy keeps asking her, “When ? When ?” and she says, “Not yet. Maybe in six months.'”

This is all he can get her to say. ‘‘Be a good girl,” he tells her as he sadly goes away. And into her hand he has slipped ten cents with which she afterward buys two red apples. The Hungarian Society will find her a position as a domestic. Some day when she gets lonesome enough she will write Jan to come and see her.

Katarzyna Tobay, wide-waisted and red-cheeked, is given to her husband, who has been here a year. They meet with a great happiness shining in their eyes, and he kisses her almost reverently. Then she opens the bundle she carries so close to her breast.

SHE shows him something soft and wonderful and pink he has never seen before. With a hard-brown finger he touches it gently as if it might break. She says something in Magyar and he leans and kisses his son.

Angelica Ferrante in a lavender gown, and a white silk scarf over her black hair, is standing hand in hand with Gaetano Lucchio. They want to be married.

They are conducted to the missionary's room to Father Moretto, who in the afternoon will take them over to New York and marry them in the little chapel at the house of San Raffael in Charlton Street.

It is the home maintained for assisting Italian immigrants, and to Father Moretto is paroled the Italian in need of protection. There was Clementina Rosa, who came one day in her bridal gown, and there was no one waiting at the Kissing Post.

From her pockets she produced a folded paper, the “promisso matrimonio” of one Battista Maiorca. He probably had not received the letter announcing her arrival. Father Moretto took her to the house of San Raffael, and there Battista came for her.

“Let me have the girl,” he said. “I will marry her by a civil ceremony.”

“No,” answered the priest, “to you, as to her, a marriage except by the Church would be no marriage at all.”

“Well, then, let her come with me while I buy her a hat,” he urged.

“No,” said the priest, looking him full in the face until his shifting eyes fell. The girl spoke entreatingly to the man, laying her hand on his arm. But he wrenched away, the door slammed, and he was gone.

When she burst into tears, Father Moretto stroked her dark head soothingly, “There, there, my daughter. Some two thousand other girls I have taken care of in the last three years. I can take care of you.”

In the little chapel in the front room the candles burned dimly, and the white saints looked down from their niches in the wall. A home was found for Clementina with a widow and her two daughters.

With them she earns a living making flowers. Now and then as she looks out over the New York roof-tops she crosses herself and thanks God and Father Moretto who kept her safe from harm.

For Father Moretto the adoration of his people is manifest as he moves among them at Ellis Island. Not every immigrant may pass out from the Place of Tears and Kisses on the day of his arrival.

Some are detained for weeks pending the settlement of a question about their landing. Missionaries of their own nationality visit them daily. And it means much to the alien among strangers to pour out in his own tongue the story he has tried so hard to express through interpreters.

All the missionaries help, but none so radiates hope and humanity as Father Moretto when he comes to speak with the Italians. He is a young man with a smiling, sunny face. As he goes through now, the people would kiss his feet, only he laughs and will not let them.

A girl has lost her railroad ticket, and he tells her not to cry, that he will find her uncle for her. An old woman wants a letter written to her son in the West, and he will do it gladly. A woman kneeling by the wooden bench in one corner is moaning and praying. “She has been taking on terrible,” the matron of the waiting-room tells him. All night she was saying ave marias and pater nosters.

As she and her three children passed yesterday in review before the inspectors, a doctor marked with blue chalk on the sleeve of her small Lorenzo, aged seven.

And at once they were turned aside from the regular line. Lorenzo had the measles and had to be sent to a hospital in Brooklyn, and she must wait with the other children until he gets well. The interpreter told her. But she only knew that they were taking her child away.

“He will die,” she shrieked. Just as the matron now tells the priest, she “took on terrible.” He goes to the praying woman and rests a hand gently on her shoulder. She lifts a haggard face and eyes red with weeping. In soft low Italian syllables he tells her how it has to be.

Her case is not nearly as bad as is that of another woman, who sits disconsolate over by the window, whose child has the dread trachoma and must, therefore, be deported. It is really better for Lorenzo to be with the nurses and doctors.

Little by little the woman's weeping ceases and she is calm. And when the priest gently disengages the hand she is covering with kisses, she is reconciled. While she stays she will be well taken care of. The accommodations provided by the Government are really better than any to which she has been accustomed.

In the velvet-carpeted office upstairs for a number of years sat a man to whom no detail of the comfort of the people in his keeping was too trivial for personal supervision. Why, the Government one day laundered a peasant woman’s apron carelessly so that the red embroidered border all ran into the blue.

She felt as badly as might some fine lady whose Paris gown should be spoiled in dry cleaning. He, the Commissioner of Immigration, heard about it and went down to the laundry, and now all the aprons come through without fading.

He, too, had the benches put in the long aisles where the people have to wait. For, long ago, this man himself who afterward was made the guard for the gateway of a continent, came through the lines, an immigrant boy with fifty cents in his pocket, on his way to work in the coal mines of Iowa.

So even yet he knows. And there is always in his heart a brooding tenderness for the alien. It looks from his eyes in the full-length oil painting that hangs in the reception-room along with the portraits of other government officials.

Beneath that picture a Hungarian mother and her baby sat as I passed through to talk with Commissioner Watchorn. She never saw an upholstered chair before, and she was sitting awkwardly on the edge of this one, in toilsome contrast to the handsome room.

She was standing in the corridor outside waiting with a group of others before one of the numerous offices for some special examination that her case required. The commissioner, happening to see her, himself ushered her in here.

In his private office now we may see something of how he has always felt about the people of Ellis Island. One of the cases chalk marked out of the regular lines has been referred to him. Two travelers stand before him, Constantino Stavnos and a little boy, Antonios Kopelos.

A great many, little Greek boys have been stolen and worked as boot-blacks under the padrone system. It was feared this might be such a case, though the man strenuously asserted he was bringing Antonios to his father.

Even when the father had been sent for from Chicago, there had been doubt because he hadn't told things through the interpreter just as small Antonios had. And those who sat in judgment, it happened, hadn’t seen the man daily on the ferry-boat with the hungry, pleading look in his eyes.

“Come here, Antonios,” says the commissioner, kindly, drawing the boy between his knees while he orders his secretary to read him the case. “Bring in the other man,” then he says. “Now Antonios,” he asks, “which is your father?”

The boy nods with a smile toward the man who is struggling hard to keep back the tears that begin to course down his cheeks. “Suppose you shake hands with your father, Antonios,” says the commissioner, releasing him.

With a bound the child throws himself into the outstretched arms that close tightly about him. A mighty sobbing shakes the frame of the man bending above him. “There isn't any doubt where that boy belongs,” says the commissioner, using his handkerchief vigorously. “I order him admitted.”

Here and there on the walls of the great receiving station you may see posted notices that read, “Immigrants must be treated with kindness and consideration.”

It was put there by Robert Watchorn.

And this order works. Come into the Board of Special Inquiry where are heard the cases detained for more extended examination than the inspectors in the line can give.

There is a long-polished table before which sit four men to judge the merits of the case through information conveyed by the interpreter. The waiting people are in rows on the benches.

An Italian woman, Giuseppa La Rocco, with her three children, is called to the bar of the tribunal. She is gathering them up, and little Rosina is asleep. “Never mind,” says the chairman of the board kindly, “do not waken her.”

Small Pasquale, tied up in a brown shawl, trudges forward with his mother. As they begin to question her, the baby in her arms commences to cry, and another board member hunts for a cough drop in his pocket and dexterously administers it as the baby's mouth opens for a loud scream.

The woman is a widow, it develops. She has no money, and the immigration authorities must be assured of support for her and the children. She has brothers. They have been sent for and are now in the witness room. They come in, three prosperous Italians.

Two are painters and one a macaroni manufacturer, who throws his card upon the table. They smile as they readily promise, after the usual formula, that their sister shall not become a public charge. She is committed to their care. Each kisses her tenderly.

The macaroni manufacturer gathers in his arms the little niece sleeping on the bench, and the happy family party depart for the home in the Bronx.

Next comes Moses Rolfsky, a book binder from Russia, and his wife Sarah. His long beard is white, and her shoulders are bent. “I come to America to work at my trade,” he says. “In Russia I have been through riots and persecution. I was robbed on the street. They took three hundred dollars from me. They broke all my instruments.”

“How do you know you can get work in America?” asked the chairman of the board. “Everybody gets work in America,” is the hopeful reply.

But there must be more than the old man's hope to guarantee the couple's future. From the witness room is called their son, Simon, an East Side tailor. He offers bonds for their support. “And you will give your parents a home?” he is asked.

His home, a six-room flat, already teems with a family of thirteen, but he answers cordially, “Sure,” as he puts an arm about his mother and reaches a hand to his father. It is a habit of an East Side home always to have room for more.

“Our cousin from Russia is coming,” is cause enough to make up another bed on the floor. “Why, he is our kinsman.”

Among all Oriental people the ties of blood are close. Next there is called Musa Beshada. He is only fourteen, and unless the board can know that he will make a living, or someone make it for him, he will have to be excluded.

“Why, Musa, have you come so far alone to seek your fortune?” asks the chairman, and Musa tells: “At home a worm eats all the crops. Nothing grew last year that did not fail. Many people in my village are starving.

There are my aged grandparents, my mother and five children. I have come to America to my uncle that I may work and send money back to them.” The uncle, a Syrian peddler, who travels through small towns of New York State with a pack on his back is called in.

Will he look after his nephew and provide for him? Unhesitatingly he answers in the affirmative and takes the boy by the hand.

“Of course he would,” comments the Syrian interpreter with pride. “In my country a nephew is as dear almost as a son. The blood of his brother flows in that boy's veins. He bears the family name. It is a sacred duty that he be loved by his uncle.”

There is summoned Anna Czorpita. She wears a flowered kerchief over her fair hair and stands with her hands crossed one over the other. Her blue eyes survey the faces of the four men before her and her eyelids flutter.

“Tell her not to be frightened,” the chairman of the board says to the interpreter. Then they take her testimony. She is seventeen, an Austrian peasant girl traveling alone.

She is going to her betrothed husband.

HE IS Leopold Adarczyk, in Pittsburg. Why do they not let her proceed on her journey? Of course she has before been told the reason. But she has not understood. They must know who is this Leopold and whether he will be able to support her.

So they sent to Pittsburg for him to come and get her. They call him from the outer room. In her face flashes a look of glad surprise at sight of him. He starts eagerly toward her, but an attendant brings him up before the board instead.

They question him.

“You intend to make Anna your wife?”

“Yes.”

“What do you do for a living?”

“I am a musician."

“How much do you earn?”

“Fifteen dollars a week and it is to be I have the promise of a place in the orchestra at the opera house.” From his pocket protrudes one end of a flute.

“Let us hear if you can play,” suggests Leopold complies.

The notes of an Austrian love-song fill the air. At first the player is a trifle self-conscious. But as his music throbs and thrills through the room, his heart gets in rhythm with it. His eyes are on the fair haired girl, and all the board is forgotten.

They are sitting in rapt attention, and as the last measure dies away the chairman says warmly, “My! but that makes me young again. I guess you can have your girl.” Outside the door, the Austrian missionary waits to marry them.

There is one more case. Not even the board, who are used to life as it passes by their table, have wanted to come to it.

A woman sits alone on the rearmost bench. They call her, and she comes forward. Before them a record the doctors have furnished states a medical fact. In answer to the question that they are obliged according to form to ask her, she confirms it. “You are coming to your husband?” they continue.

“Yes,” she says. “And you say he has been in America two years and you have never seen him during that time?” “Yes,” she answers in a low voice, realizing the meaning of the admission.

“Bring in the husband,” slowly orders the chairman. Every member of the board looks out of the window at the sea, and the clock ticks loudly.

The interpreter now is repeating it. In eager anticipation a young man enters. He has come in answer to the postal card from the immigration authorities announcing that his wife is here.

“This woman is your wife?” asks the chairman. “Yes." “You paid her passage over?” “Yes, sent her the money. I wrote for her many times. I have a home ready.”

He is a window-cleaner, Jean Dupron by name. He earns ten dollars a week and he has one hundred dollars in the bank.

“We must tell him, gentlemen,” says the chairman as if soliciting the support of the rest in the performance of his duty.

“We regret to inform you,” he begins, “that your wife comes here,” and he reads the rest from the medical record.

The woman's face flushes and she hangs her head. The man's face is a study. It might have been graven from stone.

“Shall I tell him again?” asks the interpreter. “I guess you'll have to,” the chairman says. And they repeat the statement. There is a quiver of his shoulders as if under the lash of a whip.

“Knowing the fact, do you still wish to take your wife?” If he renounces her, she must be deported.

There is silence for a moment and a quick intaking of the man's breath. Then he answers, “Yes.” All the time he has not looked at the woman.

“Better take time to consider it. We will give you ten minutes in which to confer with your wife,” says the chairman, waving him toward the bench where she sits.

As the man turns, the woman with a sob throws herself on his breast and kisses his lips and his cheeks. He submits passively, looking into her poor, weak, pretty face with eyes that for the rest of his life will mirror something of this moment's anguish. They sit down to talk. He bows his head in his hands.

She strokes his coat sleeve entreatingly. In Austrian dialect she is telling him the story. The board turn their backs. They try to talk about the steamship arrivals, about the weather, and they note the mist that is coming up over the sea.

At length they look at the clock. “Call them up,” the interpreter is ordered.

And they come, the man's arm now about the woman's waist. He is not more than twenty-five, but his face is suddenly old. Yet through the lines of pain are lines of strength. “I will take her,” he says.

“Swear him,” the interpreter is direct ed. The man raises his right hand.

“Do you promise to care for her and cherish her and to stand in the place of a father to her child?” Outside the fog bells on the boats are tolling dismally.

“I do,” he answers solemnly.

“Then this alien is admitted,” announces the Board. And a tragedy is done and begun. Jean Dupron, window-cleaner, goes out with his wife. The chairman wiping his glasses, murmurs, “Greater love hath no man shown.”

And day in, day out, the lines at Ellis Island are moving. There is the quiver of the trembling lip, the lifted eyelid's glance, the touch of the hand, the swift embrace. Why, for this the immigrant will suffer and endure and live. He may not live so high intellectually as some who have scaled the heights ahead.

The treadmill of existence is necessarily placed over against the base of the social pyramid where some beams of light never penetrate. But he lives as deep as the wells of human affection, as wide as the waves of human sympathy.

Once you have stood at the Place of Tears and Kisses, you have found this out. For here you have seen the immigrant's soul unfold. He is no longer dull or plodding or stupid. Even sometimes before you is he suddenly glorified in the image of God in which he was made.

Daggett, Mabel Potter, “The Loves of Ellis Island,” in The Delineator, New York: The Butterick Publishing Company, Vol. LXXIV, No. 3, September 1909, p. 205, 222, 226, 228.

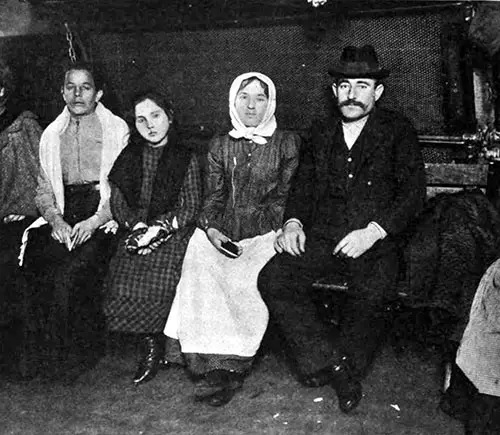

Kissing Gates of America — Friend Greeting Emigrant Just Discharged. The Maltine Company, Quarantine Sketches, 1902. GGA Image ID # 14af1b0021

The Kissing-Post

The boats steam up through the Narrows into New York harbor, toward the welcoming statue that symbolizes the spirit of our country. And the new pilgrims—pilgrims who are ignorant, and poorly nurtured, and badly clothed— enter the land of the free. And the gateway is called Ellis Island.

A wonderful system rules at this gateway. And smoothly, steadily, all the time the wheels keep rolling on, admitting the right ones, deporting the impossible kind, helping the new-comer to find a home—and a family.

"I am going to let you see the immigrants claimed by their friends," said the superintendent, as he guided us through a series of apartments, dormitories, baggage-rooms, resting-rooms and ticket-exchanges.

Swiftly he led us to a hallway that was divided into two parts. In one corner the pilgrims waited; in another their families were showing the necessary credentials. Smilingly, the superintendent turned toward us.

"Do you see that post at the doorway?" he questioned, and as we glanced at it, "Some call it the kissing-post. It is there that the long-separated families meet." And then we saw that he spoke the truth.

For, while he was talking, some excited Neapolitan in American clothes ran out of the tiny gate. At the foot of the kissing-post his family met him— a young wife and two tiny children.

And there they were reunited—at the gateway of our land! The gateway of Liberty had become their gate of Thanksgiving. —Christian Herald.