Ellis Island - The Immigration Question - A Study of Migration (1897)

Among the many problems which the rapid and restless progress of civilized mankind has created in the nineteenth century, the issue of immigration is not the least interesting. Past centuries have known migration on an extended scale; in fact, the settlement of the earth is based on it.

Empires have sprung into existence and vanished by large migratory movements, to which all the present powers owe their final development.

Such migration of tribes, which changed the fate of nations and states in single violent onslaughts, has been superseded by immigration. That is the change of the domicile of individuals and families in large numbers but without any apparent union of interests or destination.

It is no longer the conqueror of the past centuries who threatens with open invasion. Still, it is now the humble and needy applicant modestly knocking for admission, in the hope of securing at least a small share of the wealth and culture of a more affluent nation.

As long as there is an abundance to divide, as long as the newcomer can be adequately provided for without any severe loss to the older settler. And especially as long as the latter sees an advantage to himself to be derived from the labor or services of the newly arrived, immigration is welcomed with open arms.

The time comes, however, in which the "beatus possi dens" the fortunate possessor who came ahead of the new arrival, may be no longer desirous of sharing his abundance with another, or may have nothing further to divide, or may be unable to foresee any immediate advantage to be gained from the presence of such new arrival.

Then the conflicting interests of the former settler and the new arrival may assume the proportions of a severe problem.

In addition to these purely economic difficulties, there may arise the danger of social and political evil influence. Through the arrival of too high a number of heterogeneous immigrants, which may threaten the progress and welfare of a highly civilized nation.

Then indeed, by the supreme law of self-protection, the state authorities would be obliged to interfere in the interest of the freedom, happiness, and culture of their subjects.

If we may judge from the denunciations hurled from some of our more popular pulpits, as well as from editorial chairs, public meetings and debates in Congress, such a critical stage in our public life has actually appeared, and our economic as well as social and political life has been and is still threatened with the highest possible danger from such immigration.

In the four years of my official life, as chief gatekeeper of the United States, I may freely state that of the many strange and unaccountable things with which I have been brought in contact, nothing has surprised me more than the conspicuous and permanent ignorance of the public at large about the actual condition of immigration matters.

For more than five years the port of New York, which handles about four-fifths of the entire immigration to the United States, has enjoyed the privilege of a particular immigration station, established, on a large scale and with every improvement, on Ellis Island, in the harbor of New York.

Nevertheless, it is found that not only immigrants but also citizens of the United States still speak and write of Castle Garden, which was the great receptacle for immigrants for nearly forty years, as the present point of landing.

For eight years, the old State Board of Commissioners of Immigration, which formerly consisted of the mayors of New York and Brooklyn, the presidents of the German and Irish societies, and six other commissioners appointed by the governor of the state, has been superseded by one United States Commissioner of Immigration.

Nevertheless, it is a common belief, shared even by a large number of editors, that a Board of Commissioners still exists for the control of immigration at this port.

The same anachronism exists about the immigration laws and their enforcement, and the ignorance regarding the number and character of immigrants of past years and their handling by the federal authorities is almost as profound.

Now it is true that in years gone by, we have had as many as eight hundred thousand immigrants arriving in a single year at the various ports of the United States, not counting those who simply cross over the borders of neighboring countries into the United States.

It is undoubtedly true that out of that very heavy immigration, a comparatively large portion became charges upon our public institutions or, through the assistance of unwise and antiquated naturalization laws, were permitted to assert an undue influence in our public affairs.

It is further undoubtedly true that, during years gone by, communities and private associations in Europe freely unloaded their charges upon the United States, without the formality of any question or restriction on the part of our laws, or concern by our officials.

If such conditions still obtained, or if they had prevailed during the last four years, I should have been among the first to say, "Stop it, and stop it at once, most energetically and efficiently, in the interests of American liberty, American welfare, and American civilization."

I am, however, in a position to declare and to prove that such unrestricted immigration has, for some years, been a thing of the past and that massive immigration has been made practically an impossibility for the future.

History of Immigration to America

In the face of actual facts, that part of our Declaration of Independence appears indeed like a glimpse of ancient history, which records, among the injuries and usurpations on the part of the King of England, his endeavor "to prevent the population of these states, for that purpose obstructing the Laws for the naturalization of foreigners, refusing to pass others to encourage their migration hither."

As late as 1864, a law was passed by Congress to encourage immigration, in which no safeguards whatever were provided to protect us against the dangers to be expected from the very worst refuse of foreign population.

Even in 1872, attempts were made in Congress to pass new laws promoting immigration. The first law of any restrictive character was passed in 1875 to prohibit the importation of prostitutes from China and Japan.

Still, it was not until the year 1882 that the law to regulate the landing of immigrants in this country was passed. In fact, it was not until 1891 that any legal examination was required.

The most radical change in our laws, and in the practical enforcement of them, was introduced by the Act of March 3, 1893, which I have had the privilege of putting into actual execution on Ellis Island since the beginning of May of that year. Since that time, it may be said that immigration has, in the broader sense, almost come to a standstill.

The number of immigrants landed since the enforcement of the new law of 1893, that is, such as may properly be called new arrivals, is actually hardly more significant than the average immigration into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

At the same time, the number of immigrants debarred from landing has increased to a marked degree. However, by the provisions of the same law, the most significant part of the really undesirable immigrants are, a trim, deterred from even embarking for the United States.

On the other hand, the number of foreign-born persons who have become public charges on our American communities or public institutions has mostly decreased.

Furthermore, there is, under the present law and its enforcement, no necessity and, I may say, with proper administration by our American municipal or state governments, no possibility of any alien becoming a permanent public charge. These statements may appear to be sweeping and may create some surprise. Still, I am fortunately in a position to verify them.

I have taken especial pains to determine the actual immigration under the new law, and, with this end in view, I have directed the statistical force at my command on Ellis Island to ascertain in the most detailed and reliable manner the number of aliens arriving, and to arrange them according to nationalities.

This allows us to determine who had been in the United States before or who came here to join members of their immediate families. That is only immigrants related in the first degree, such as children, parents, brothers, or sisters. Last year this method was adopted for the entire service.

It will be readily conceded that neither of these two classes can be appropriately called immigrants, nor do they, if not per se, belong to the excluded categories liable to add to the dangers experienced through former immigration. These are the surprising figures for the port of New York:

| Fiscal year | Total landing | In the United States before | Came to join immediate family | Leave as immigration proper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1893-4 | 219,046 | 29,782 | 90,887 | 98,377 |

| 1894-5 | 190,928 | 45,280 | 69,637 | 76,011 |

| 1895-6 | 263,709 | 48,804 | 95,269 | 119,636 |

Finally, for the calendar year 1896, out of 233,400 arriving 190,928 Island, only 108,563 could be classified as immigrants proper.

The above figures will conclusively prove to any thinking person that the total immigration to the United States has, within the last four years, fallen to such small data as to be absolutely insignificant as compared with our own enormous population.

It is worthy of note that with such nationalities as are generally regarded least desirable, the proportion of real immigrants to the total immigration is an unusually small one.

To illustrate in figures, out of 42,074 Italians in 1893-94, fully 8,111 had been in the United States before and is, tot came to join members of their immediate families, thus leaving only 18,862, a little over 40 percent, as the immigration proper for that period.

Out of 28,736 Russians the same percentage, only 12,099 may be appropriately called immigrants. On the other hand, out of 38,711 Germans fully 20,641, or nearly 60 percent, were new immigrants.

In this way, the much-dreaded immigration from nationalities more foreign to us dwindles very considerably under proper analysis.

The immigration authorities readily admit that a large share of the credit for the remarkable decrease in immigration during the last few years is due to the unprecedented financial crisis prevailing. However, they also assume some share of the credit for themselves.

The "lynx-eyed" officials at Ellis Island have, I may venture to say, become almost proverbial abroad and only too well known to the steamship companies and their agents, upon whom rests the full financial responsibility for all immigrants who are not "clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to admission." A few significant figures will serve to indicate the direct effect of the new law and its rigid enforcement:

- During the fiscal year 1891-92, out of some 445,987 landed in New York only 1,727, and in 1892-93 out of 343,422, not more than 817 were excluded.

- In 1893-94, from a total of but 219,046, fully 2,022 were debarred from landing.

- In 1894-95, out of 190,928 aliens arriving, 2,077 were debarred from landing at Ellis Island.

- In 1895-96, out of 263,709, no less than 2,512 were debarred from landing at Ellis Island.

While in this way, notwithstanding a continually decreasing immigration, a continuously more significant number of would-be immigrants was debarred from landing, the number of persons returned within one year after landing as public charges from the whole United States decreased from 637 in the fiscal year 1892 to 577 in 1893, 417 in the fiscal year 1894, 177 in 1895, and 238 in 1896.

It will thus be clearly seen, from the preceding figures, that the enforcement of the immigration laws during the last four years has been very much more efficient and beneficial than at any time before that.

The number of immigrants debarred from landing, as above indicated, increased absolutely and relatively, and with them increased the amount of the most efficient of the anti-immigration agents, i. e. those who endeavored to come here in violation of the law, but were detected through the vigilance of the immigration authorities, and compelled to return to their native countries, there to spread the story of the difficulty experienced in meeting or getting around the strict immigration laws of the United States and their rigid enforcement.

As to the number of those who have been refused tickets by the steamship companies, or who have been deterred even from risking their money in the purchase of passage, it is hardly possible to estimate the amount in full accurately; however, the number has unquestionably reached hundreds of thousands during the last few years.

On the other hand, as the number of those becoming public charges within one year after the time of landing and who were returned at the expense of the steamship companies, under the law, became so small, very few persons likely to become public charges could have evaded the inspection of government officials.

It is necessary to give an outline of the methods of our present inspection to explain the possibility of such results. However, I am convinced that no mere explanation could be so satisfactory as a visit to that unique institution at Ellis Island, the immigrant station of the port of New York.

I do not hesitate to state that it is absolutely impossible to get an intelligent idea of the letter and spirit of the present law, with its efficient enforcement, without such a personal observation.

The fundamental principle of our present immigration laws consists in placing the full financial responsibility for all undesirable immigration directly on the steamship companies.

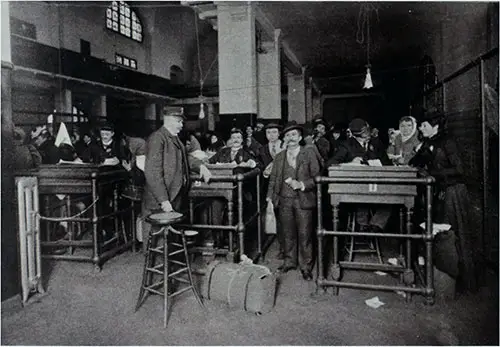

Final Discharge From Ellis Island—the Emigrant Showing Passport, Money, and Answering Questions With a View to Ascertaining Whether He Is Likely to Become a Charge on the Country, Is Amenable to the Contract Labor Law, Etc. The Maltine Company, Quarantine Sketches, 1902. GGA Image ID # 14ae20fc90

They are obliged to conduct a personal examination through their agents, of all intending immigrants, not only as to the general qualifications of age, sex, married or single, calling or occupation, nationality, last residence, final destination, but also as to the ability to:

- read or write,

- whether such immigrant has a through ticket to the point of final destination,

- whether he has paid his own passage or whether it has been paid by another person or persons, or by any corporation, society, municipality or government;

- whether in possession of money, and if so, whether upwards of thirty dollars, and how much, if thirty dollars or less; whether going to join a relative, and if so, what relative, his name and address;

- whether ever before in the United States, and if so, when and where; whether ever in prison or almshouse, or supported by charity;

- whether a polygamist;

- whether under contract, express or implied, to perform labor in the United States;

- and finally as to the immigrant's condition of health, mentally and physically; and whether deformed or crippled and if so, from what cause.

Responsibilities of the Steamships and Steamship Lines

The steamship companies are obliged to have complete ships' manifests, containing replies to each of these twenty questions, and sworn to by the master of the vessel and the ship's surgeon, in the presence of a United States Consul, before embarkation.

By a simple arrangement of dividing all passengers of a single ship into groups of thirty or less, and of providing each immigrant with a ticket, containing the numbers of the sheet and of his own entry on the same, for the purpose of identification, it is made possible to bring each immigrant in turn before an inspector who has the sworn statements of the steamship company about the immigrant before him and is thus able to intelligently control the matter by his own re-examination.

As soon as any steam or sailing vessels reach the Quarantine Station of any port in the United States, such ship is boarded by immigrant officials, at the same time, the customs officers arrive.

While the last-named busy themselves in seeking to discover violations of law in the importation of merchandise, the officials of the immigration bureau inspect the ship as to her arrangements for immigrants, especially in the steerage, and conduct a general inspection of cabin passengers, because it has been found by practical experience that no small proportion of undesirable aliens come as other than steerage passengers.

While this inspection is going on, the proud ship proceeds on her way through our most wonderful and beautiful Bay, which extends in all its grandeur between Staten Island, New Jersey, New York, and Brooklyn; she passes the imposing Statue of Liberty and immediately afterward the immigration station at Ellis Island, which, though just under the eyes of this Statue of Liberty, for the proper protection of the country, has, unfortunately, to be surrounded and guarded in such a manner as more to resemble a prison than an institution of a free and enlightened nation.

When the ship reaches her dock, all citizens of the United States, even though coming in the steerage, are discharged by the proper immigration officials, upon the production of sufficient proof of their citizenship; while all other steerage passengers are brought in special boats provided for the purpose to Ellis Island for further inspection, according to law.

Here, on the large main floor of the building erected by the government for this purpose, they pass before the critical and scrutinizing eyes of the matrons and the officers of the medical staff, who examine their physical condition.

After this, they must be further investigated as to their eligibility to land, by inspection officers who stand at the heads of the various aisles prepared for the purpose.

It is the duty of every inspector, and to this, I would call especial attention, to detain for a special inquiry every person who may not appear to him to be clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to admission.

All such special inquiries are conducted by not less than four officials, acting in the capacity of judge and jury, and no immigrant is permitted entry by the said board except after a favorable decision made by at least three of the inspectors sitting in such judicial capacity.

It depends entirely upon the character of the immigrants, as to how large a proportion of the passengers of any incoming ship has to be detained for such special inquiry.

Giving the Green Light to English, German and Scandinavian Ships

We have had English, or German, or Scandinavian ships where 5 percent or less did not appear to be dearly and beyond doubt entitled to admission, and where, after a special inquiry, perhaps not one of the detained immigrants had to be finally returned as undesirable through their exclusion by law.

And we not infrequently have ships from Italian ports where 50 percent and more have been detained for special inquiry, resulting in the final debarring from landing of some 20 percent of such number.

The simple fact that 24,000 cases in 1894-95 and fully 40,539 in 1895-96 (43,645 in the calendar year 1896) were brought before our Boards of Special Inquiry speaks volumes not only for the amount of work to be performed under the present law on Ellis Island but also for the meticulous care exercised in the winnowing process.

Any immigrant who is held or sentenced to be returned is permitted to consult with counsel and friends, under proper restrictions, and to file with the commissioner an appeal from the excluding decision of the board; while in cases of exceptional merit even immigrants who may not be eligible per se to admission are permitted to land if the authorization to accept a real estate bond to the amount of $500 in each case, conditioned that the immigrant will not become a public charge, is given by the Secretary of the Treasury.

During the entire examination, which sometimes consumes several weeks, the detained immigrants are appropriately housed and fed at the expense of the steamship company bringing them here, and, if ailing, are received in the hospital and treated, without expense to themselves, but at the cost of the steamship company. The company also has to stand the expense of returning all immigrants not permitted to land.

From these facts, it is evident that the steamship companies in their own interest, will be and are very careful before issuing tickets to such persons, and that they will and do necessarily exercise especial care before issuing tickets to those whose examination alone, not to speak of the return, results in an expense which in many cases is larger than the price of the ticket.

As the steamship companies hold their agents who have sold such tickets for them, responsible for the outlay in each case, it naturally follows that the agents themselves exercise greater vigilance in the conduct of their business.

Returning the Undesirables

Still another safeguard has been provided for the protection of our country in the law a section of which requires the return of all aliens at the expense of the steamship company who come into the United States in violation of law, and that any alien who becomes a public charge within one year after his arrival in the United States, from causes existing before his landing therein, shall be deemed to have come in violation of law and be returned.

In this manner, the responsibility of the steamship companies is practically extended over one year after the landing of immigrants. However, when on proper examination it is found that any immigrant has become a public charge within one year from the date of arrival, from causes not existing before that, and that he has been permanently incapacitated from earning a livelihood, he shall be returned at the expense of the Immigrant Fund, which also bears the cost for the care and maintenance of any immigrant suffering from a disease of temporary character until the expiration of one year from the date of landing.

The complaint formerly prevalent that our almshouses, insane asylums, and hospitals were overcrowded with newly arrived immigrants, will, therefore, be found to be no longer well-founded.

If, however, such public charges do exist, it is solely through negligence on the part of municipal or state authorities, who have failed to avail themselves of the opportunities given by law, and invariably most willingly rendered by the immigration authorities.

While I have hitherto endeavored to show that there is a rigid inspection of all immigrants going on under the new laws and that therefore complaints which are based upon former methods and their results can no longer justly be made at this time, I do not wish it to be understood that our present laws or their enforcement are perfect or beyond improvement.

On the thirteenth of June, 1894, the Secretary of the Treasury appointed a commission consisting of three practical immigration experts to investigate and report among other points what changes, if any, in the rules and regulations now in force were necessary to secure a more efficient execution of existing laws relating to immigration; and this commission, of which I had the honor to be a member, recommended in its report, submitted in October, 1895, no less than twenty-nine practical amendments to the existing laws and regulations.

Still, this same commission was and is unanimous in the opinion that the fundamental principle of the present law should be upheld and that the current laws, with certain practical amendments, under proper execution, are quite sufficient to protect this country against too massive or undesirable immigration.

The Immigration Investigating Commission, for reasons sufficiently explained above, does not believe in the necessity of heroic measures at this time.

We do not underestimate the dangers coming from unrestricted immigration. Still, we do believe, and are sincere in that belief, that there is not, and has not been for the last four years, any unrestricted immigration.

Our eyes are not closed to the evils which a sizeable foreign population, concentrated to a considerable measure in our larger cities, and unfortunately in many states invested with the full power of citizenship, may bring to our political institutions, nor do we overlook the fact that the competition of less civilized workmen, who have never been used to a higher standard of life, is liable in turn to lower our standard of wages.

But we do believe that any and all of these dangers and evils can be more successfully overcome and avoided than by introducing such methods of restriction as are likely to exclude the most desirable immigrant, while not helping us about the many millions who have already come here under the unrestricted condition of previous years.

Referring primarily to the evil political influence which an ignorant foreign-born population is likely to exert in our public affairs, I am personally of the opinion that the dangers from that source are very much exaggerated in a country where suffrage is distributed with so little discrimination that millions of half-savage Negroes enjoy the right of suffrage. At the same time, our intelligent and highly cultured women are precluded from availing themselves of its privilege.

But suppose the ignorant Pole or Italian is a more dangerous citizen than the ignorant Negro. There is nothing easier than to apply the severest test to the privilege of American citizenship, granting naturalization only to the enlightened and completely assimilated foreigner.

Let us not forget that immigration is and will be first of all a virtually economic question. At the same time, naturalization is a purely political one. What, in fact, ought to be no more than hostility to the ready naturalization permitted in many states, turns out, by an inexcusable confusion of ideas, to be a general hostility to immigration.

A number of those interested in the subject have hoped to solve the immigration problem through the introduction of a monetary test; however, this method cannot stand any close scrutiny.

The mere exhibition to the inspection officer of $200 or $1000 at the time of landing is not a sufficient guarantee that a person will not become a public charge within a short time, even if this money was not borrowed for the very purpose of an exhibition to such inspection officer.

It will be readily conceded that a young man with two dollars in his pocket, two good strong arms and an earnest intention of engaging in any kind of available work will, as a rule, find his way in this country; while a widow, hampered with several small children and without friends, could never convince me, even by showing as much as $5000, that she might not within a given time become a public charge.

A bankrupt merchant, unused to work, and coming over here perhaps with many hundreds of dollars, will almost invariably have to spend his last cent before finding any opportunity of earning a livelihood.

Another solution which has been proposed and much agitated is the plan of adopting Consular certification, but, in the words of Senator Lodge, " This plan is impracticable; the necessary machinery for it could not be provided, and it would lead to many serious questions with foreign governments and never be properly and justly enforced."

According to the Senator's declaration, the opinion of the committee of which he was chairman is shared by all expert judges who have given careful attention to the question.

Another method, involving a higher capitation tax, is appropriately designated by the Senate Committee's report as a severe but somewhat discriminating method for which the country is not yet prepared.

The Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League has finally decided, I may say after consultation with the officials on Ellis Island, to forego all those plans which were favored in former times and to adopt as their only demand the introduction of an educational test. I am in favor of a moderate academic test for the protection of American civilization and of the American standard of life.

Illiteracy is invariably coupled with a low standard of living, which inevitably leads to a lowering of wages. Under the present condition of education in Continental Europe, those nationalities which are considered as sending the most desirable immigrants to the United States, such as the Germans, English, and Scandinavians, are those which show the smallest percentage of illiteracy; while the southern part of Europe and the eastern part, which teach a low grade of education, furnish at the same time the least desirable immigrants.

However, with the progress of compulsory education in Europe, and especially, strange as it may sound, with the growth of mandatory military service, illiteracy is rapidly waning in all Europe, and any literary, educational test will, within twenty years or less, be entirely superfluous as far as Continental Europe is concerned.

In the meantime, it would undoubtedly appear extremely unjust to apply such tests to persons under sixteen years of age or to females, or in any other way that might lead to a separation of families, or to an aggravation of our severe and vexed servant-girl question.

With these limitations, I believe in the introduction of a limited and practical educational test, as a natural and proper addition to the present immigration laws, to be made without otherwise radically changing their fundamental character; and I may add that since October 1, 1896, I have practically introduced this test on Ellis Island without being forced by law.

One of the chief reasons for the introduction of this literary test at the station under my charge was shown by my practical experiences during an official trip to Europe last summer, where I observed that the statistics about the illiteracy of immigrants are, if possible, even less reliable than I have found general immigration statistics of former years.

That there is a tremendous discrepancy between the statistics as to immigrants arriving within the last quarter of a century and the results of the three United States censuses taken at the same time, is a fact generally recognized.

Our Bureau of Statistics has, of course, been obliged to rely on information gathered most carelessly and recklessly by so-called officials of state agencies.

We are confronted with figures as to age, occupation, destination, literacy, and money in possession of immigrants, which I can positively assert, from researches personally made, were, up to the enforcement of the law of 1893, based almost entirely upon guesswork.

Not only scholars and scientists but also legislators have been naturally misled by such erroneous premises and alleged facts to equally erroneous conclusions.

Even since the enforcement of the Act of 1893, which for the first time legally required an examination and sworn statements on these points, it has been found a most challenging task, requiring more skilled material in expert statisticians than public service in the United States usually furnishes, to secure reliable statistics.

Further, about illiteracy, I have found by practical experience that it is positively necessary to demand some functional tests to arrive at reliable and definite figures.

The results of an actual test on Ellis Island made during the last six months shows a marked divergence from data heretofore promulgated:

| Emigrated From | Current Percent | Prior Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Bohemia | 4.7 | 11.45 |

| Galicia | 39 | 60.37 |

| Other Austria | 22 | 36.38 |

| Hungary | 29 | 46.51 |

| France | 3.9 | 4.88 |

| Germany | 1.6 | 2.96 |

| Greece | 13 | 26.21 |

| Italy | 39 | 54.59 |

| Russia | 31 | 41.14 |

| Poland | 36 | 47.78 |

| Turkey in Europe | 8.8 | 31.43 |

This inaccuracy in the statistics formerly furnished as to immigration is, in my opinion, one of the most persuasive arguments against the advisability of any heroic change in our present immigration laws which, for the first time in our history, make it possible for us to secure reliable statistics, that may be used as safe bases for scientific and legislative conclusions.

But the introduction of such an educational test cannot solve the immigration problem, the very essence of which it fails to touch.

"The immigration question," I quote from the commission's report before referred to, ' 'is pre-eminently a national, one; this nation consists neither of a few large cities, which, as in all the other countries furnish only limited employment to a dense population, nor of the few states whose farms are deserted and whose manufacturing cities are overcrowded with idlers.

Immigration concerns the West no less than the East, and the South as well as the North, and the only line of policy which can be consistently recommended is one which will benefit the whole country most and harm each part of it the least.

"No one can undertake to deny that an entire closing of our ports to immigrants would inevitably result in untold injury to, if not the very annihilation of, our largest transportation and manufacturing enterprises; in a disastrous stoppage of the development of significant sections of the country; and in a famine of servants and menial laborers.

"There are some comparatively small densely populated sections to be sure where no immigrants or only the most highly qualified are desired, but in the more substantial part of this country, those immigrants are still needed who are only fitted for unskilled manual labor.

This is particularly true of the vast undeveloped agricultural and lumber areas of the Northwest, South, and Southwest.

"At present immigrants herd together in the densely populated centers. Nearly half of the steerage arrivals at the port of New York, for example, give their destination to the immigrant inspectors as New York City, because they know of no other place to go.

That a considerable proportion of them eventually drift elsewhere, for better or worse, is evident from the figures of the census. Still, quite too large a portion remains to swell the ranks of the paupers or depreciate the labor market.

Only a small percentage get where they really ought to be-that, into the work for which they are peculiarly noted.

Existing conditions, in a word, exhibit a clear case of maladjustment, and the maladjustment is principally due to the lack of accurate knowledge on the part of the immigrants and their complete inability to obtain it.

"Notwithstanding the rapid mail and cable connections and the enormous transatlantic trade, the geography, topography, resources, and industrial and social conditions of the different sections of the United States are practically unknown in Europe.

The only information accessible to an intending immigrant is contained in the letters received by himself or his neighbors, or in the circulars of speculators and steamship and railway companies.

He leaves home finally with the expectation of abundant opportunities of bettering his condition and with an eager determination to avail himself of them but without any precise knowledge of where or how he is to do it.

Under the circumstances, it would be strange indeed if glib-tongued agents did not sometimes, despite all the vigilance of the federal authorities, induce him to invest his funds in worthless lands and played-out enterprises, or to let his labor to an unscrupulous padrone."

Hit Rhodus hic salts, here is to be found the point where the real solution of the problem follows as a natural sequence: Let each immigrant receive the proper information, enlightenment and guidance, so that he may readily find the place where he can work with the best advantage to himself as well as to his adopted country.

Give him opportunity and the knowledge to find the proper labor market, where his services are actually needed; not in competition with American labor but for the building up of all sections of this great country and of all its industries.

Let the farmer or fruit-grower be shown to those sections of the country where his experience and personal qualifications will secure him the most significant returns. You will very seldom hear any objection to, or outcry against, immigration.

Exclude all undesirable, and at the same time, see that the most desirable immigrants are adequately distributed over the country, and there will no longer be any immigration problem.

Do not turn over the distribution of the incoming to irresponsible speculators or padrones, but place the distribution of settlers as well as of laborers under the responsible management of a National Land and Labor Clearing House, in close connection with, and under full regulation by the authorities charged with the enforcement of the immigration law.

This great National Land and Labor Clearing House is the instrumentality by which the whole immigration problem can be removed for all time, by which all possible dangers from immigration can be prevented, and this nation is given all the benefits in the future which it has unquestionably derived from immigration in the past.

Joseph H. Senner, "The Immigration Question." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, July 1897.