Solving The Immigration Problem (1904)

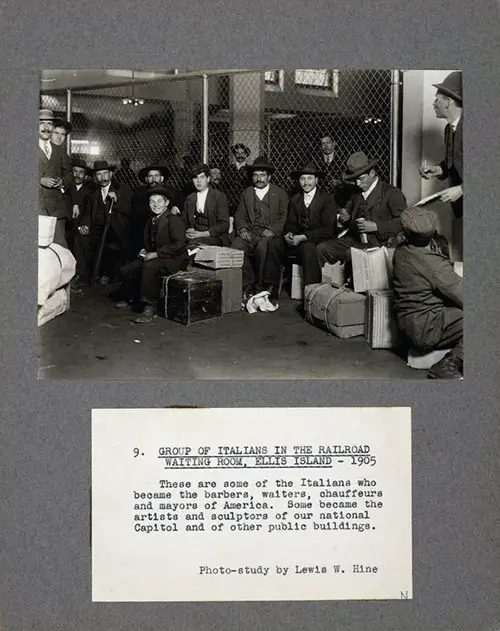

Photo 9. Group of Italians in the Railroad Waiting Room at Ellis Island, 1905.

These are some of the Italians who became the barbers, waiters, chauffeurs, and mayors of America. Some became the artists and sculptors of our national Capitol and other public buildings.

Photo Courtesy of NYPL Photo Study by Lewis W. Hine.

IT is an undeniable and inspiring fact that, no matter how grave may be any problem attracting public attention, there will always be a group of men actively engaged in the endeavor to solve it. It matters not whether the problem affects us directly or indirectly, so long as it involves a principle, there will always be found men and women who, while countless others are discussing it, fearing it, prophesying about it, will bravely face it and work for its right solution.

We hear a great deal nowadays of the "problem of immigration;" orators and statesmen, newspapers and magazines, never lose the opportunity of talking of the " foreign peril," of the danger from an influx of immigrants who do not readily assimilate with the elements and institutions of the Republic.

Indeed, many of our sins we conveniently saddle on the stranger, finding in him the responsibility for some of the evils of our own making. And so a thoughtless majority fails to see that such procedure can result only in race prejudice, and prevent rather than foster that very assimilation which we all desire.

On the other hand, how seldom do we hear of the work of those men and women who, while their companions discuss, are toiling to solve, this problem of the incoming stranger. It is true that, now and again, we get picturesque descriptions of what the agents of the various immigrant societies do at our ports of entry, or of the scenes, pitiful or humorous, witnessed before the Courts of Special Inquiry at our immigration stations.

Our knowledge of the field of labor of immigration societies, however, stops there. We know, in a vague way, that the Irish and the Scandinavians and the Jews maintain missionaries or agents who welcome the immigrant of their respective nationality, and perhaps find him work. But there is much more than this that such societies do, as a brief history of one of them and of its work will show.

I choose the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants for other reasons than that my knowledge of its work is more extensive than that of no less beneficent ones.

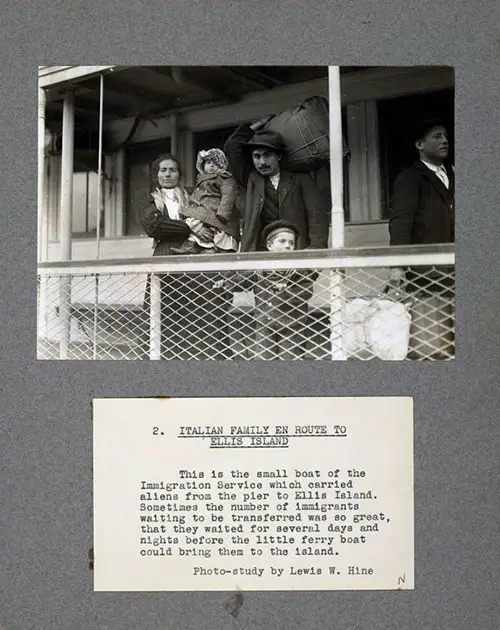

Italian Family en Route to Ellis Island. Photo Courtesy of the NYPL.

In the first place, it has the distinction of being the one immigrant society founded, not by " foreign Americans," such as the German, the Austro-Hungarian, or the Scandinavian, not by any religious sect or division, such as the Leo Haus, the Methodist Mission, or the Jewish Society, but by native Americans banded together by a love for Italy, without ulterior motive, either political or religious, except the desire to help the sons of a country to which humanity still owes a great debt.

This is not only an honorable distinction, but an encouraging sign of a practical solution to the immigration problem. My choice was deter. mined, moreover, by the fact that Italian immigration is decidedly on the increase, and any body of men actively engaged in solving the peculiar questions which the Italian immigrant presents deserve special attention.

The Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants was founded about two years ago by some fifteen people, most of whom were that type of men and women whom many would have classified as "dreamers "—settlement workers, reformers, philanthropists 1 They, however, had the wisdom to formulate a constitution setting forth such practical objects as these:

The objects of this Society shall be:

- I. To afford advice, information, aid, and protection of all kinds to Italian immigrants.

- II. By assisting, wherever possible, such immigrants as are unfamiliar with the language and customs of the country to a practical knowledge thereof.

- III. By learning the character of the labor for which each individual immigrant is best fitted, and endeavoring to procure for said immigrant employment, at his particular trade or calling, or at some remunerative occupation, that he may not, through want of work, become a charge to the State or an enemy of society.

- IV. By investigating and remedying, if possible, all abuses to which Italian immigrants are exposed, and all wrongs inflicted upon them.

- V. By familiarizing immigrants with their rights and duties under the State and Federal Constitutions, and securing for them the entire enjoyment of all their constitutional rights.

All these seem simple enough on reading; indeed, it might be said that, being for the immigrant's benefit, the immigrant will be only too glad to meet the Society's efforts. But this reasoning overlooks the forces which operate against the exercise of such good intentions and purposes.

First of all, you must overcome the immigrant's suspicions, and this is not a simple matter. The examination he undergoes by the Federal officials is a valuable and necessary thing, but put yourself in his place and you will see that if you had to answer the questions put to him, either you would refuse to answer them as impertinent, or else assault the official for making them; at all events, you would not think you were being welcomed to the new land.

Then, having passed this necessary examination, his first experience in the land of the free is likely to be his acquaintance with the boarding-house " runner," who will force him to go with him, or the crook who will exchange his foreign money into Confederate notes or take it without even such souvenirs of the transaction, or the " friend " who will take him to the banker and padrone who want to sell' his labor, or the district boss who will " Americanize " him for the sake of his vote.

Perhaps if he is fortunate in escaping these, he will experience the pleasure of what it means not to understand the policeman's " gaw on! "

It is obvious, though too often forgotten, that the first impression the foreigner gets of a new country will tend to color all his future opinions of and experiences in that country. It is natural, therefore, that immigrants' societies should concentrate their efforts in minimizing the bad impression that the alien is apt to get on his arrival.

This is especially important as regards the Italian, who is proverbially sensitive and inexperienced. Yet the work the representatives of the various immigrants' societies have to do at the landing station is, in a sense, very simple. It may be summed up in the words " lending a helping hand."

In the rush and excitement of handling some four thousand immigrants in a day by the Federal authorities, a little kindness, a word of advice, a reassuring promise in the tongue of the immigrant, will go far not only in helping the alien but also in aiding the authorities in expediting the trying work of examination.

In the case of Italians, the absence of a correct address to which they may be sent is a common source of trouble. This is due either to the use of phonetic spelling of American names or the absence of the house number. Thus " Chrippocricks " may be the immigrant's address for Cripple Creek or it may be simply Elizabeth Street. In that case the Agent of the Society goes to that section of Elizabeth Street where the fellow-townsmen of the new arrival reside, and there generally finds the immigrant's friends or relatives.

The Agent's work is not, however, always so simple. There are immigrants who, through failure properly to present their case, are ordered deported, or others against whom a strict application of the Federal laws would work an injustice. The Agents take up such cases before the Immigration Boards and endeavor to overcome the obstacles, which often are due to misunderstanding.

The moment the immigrant is " passed " by the authorities, he ceases to be in charge of Uncle Sam, and it is then that the immigration societies have to exercise special vigilance to save their charges from those various persons who are ready to pounce upon them at the landing.

The Italian Society has established at Ellis Island a corps of uniformed watchers who take in charge all those immigrants who desire to place themselves in the care of the Society. These watchers put tags of identification on the immigrants, and bring them over from Ellis Island to the Battery Landing in New York, where other uniformed guards take them in charge and conduct them to the Society's office at 17 Pearl Street.

Immigrants Seated on Long Benches in the Main Hall at Ellis Island

is at the Battery Landing that, before the corps of watchers bad been organized and the efficiency of the police increased there, open fights used to take place between the Agents who had charge of the immigrants and the " runners" and crooks who tried to get them away.

To give an idea of the aggressiveness of the powers that prey there, I might cite an instance where, of thirty-six immigrants in charge of the Society's Agents, only seventeen were left after an encounter with the runners. On another occasion the police reserves had to be called out. Nor is the drawing of weapons and the slashing with knives entirely done away with even now.

From the office of the Society the various immigrants are sent to their destination in the care of guides whose possible dishonesty Is checked by a system of cards and receipts and whose charges for services are fixed by the Society. By this method the usual rate charged immigrants for transportation to their destination has been cut down from an average of $4.50 a head charged by the runners to about 34 cents each.

An immigrant society could hardly render efficient service without what is known as an information bureau. Only men of the utmost patience and of pretty wide knowledge can be employed in such a bureau. To it the foreign-born goes for almost anything he does not know. Ostensibly it exists to supply information to friends and relatives of expected or detained immigrants.

Actually it is a dispenser of all sorts of information. Foreigners come to it for legal advice, for financial aid, for instruction regarding how to act or what to do in the new land, even for matrimonial advice. In the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants the man in charge of the information bureau also performs the important function of transmitting or distributing money from friends of detained immigrants.

Last year it handled over ten thousand dollars in sums not exceeding fifty dollars. An employment bureau is a necessary adjunct of every immigrant society. In the Jewish society young immigrants are sent out to try their luck as peddlers, being intrusted with a small stock. This is a most practical method for people of that race.

The Austro-Hungarian and Irish societies try to supply the servant demand.

The employment bureau of the society for Italians has a peculiarly difficult problem. It has made it a fundamental rule to place applicants only in out-of-town work; it will do nothing for men who want to labor in the city. In this it again contributes to the solution of the problem of immigration. For it cannot be denied that the problem of immigration with us is essentially one of distribution.

The demand for laborers is great outside of the cities, but the gregarious Italian prefers to increase our menacing urban congestion instead of going to the country. The Society, in its endeavors to relieve such .congestion, is forced to find work for large gangs of men as an inducement for them to leave the city.

An even greater difficulty lies in the fact that a successful labor bureau for Italians in competent American hands means the breaking up of the much talked-of padrone system. The padrones recognize this, and are actively using their great influence against the Italian labor bureau.

It will be apparent, after this summary, that the underlying aim of the work of immigrant societies, and more especially- of the society for Italians, is to make their wards fed that their advent into a strange land does nor mean their coming among those who wish them ill. By practical work the societies engender a feeling in the newcomer that the Republic holds friends ready to help him.

But with the sensitive Italian the work of friendly aid cannot stop here. He is probably the most complex character that comes to our shores, and the least understood by us. In a way he is the most helpless, not because he lacks strength or intelligence, but because he is often ignorant, childlike in his confidence once won, and highly impressionable to small matters.

Moreover, he is helpless in the sense that, unlike the Germans and the Irish, he possesses no political influence whatsoever, and his race in America has not yet won the prestige which would come from having among us many Italians or Italian-Americans either of affluence or distinction.

It is in supplying this very prestige that the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants, as a body of Americans of distinction, is really performing its greatest good. And it is this peculiar function which differentiates it from other similar societies; it is in this regard that we must look upon it as the most practical example of a way out of the immigration difficulty. What has it done to live up to this responsibility?

I will not enlarge on how it won the confidence of the immigration authorities; suffice it that it has never been accused of encouraging immigration. Neither will I enlarge on the fact, of which we may well be proud, of a body of Americans winning such complete confidence from a foreign government as this Society has won from the Government of Italy.

I shall describe, rather, two instances in which remarkable results were achieved by Yankee promptness and sheer force of influence begotten by the spectacle of determined Americans insisting on fair play for the stranger within the gates. For a long time the Government of Italy had sought, through diplomatic channels, to put an end to what was practically white slavery of Italians in the phosphate mines of South Carolina.

But the protestations of a foreign power are seldom effective with public opinion, because they savor either of intermeddling or of interestedness. In this case they availed nothing. The Society took up the complaints, carefully ascertained their truth, and promptly gave a National publicity to the facts. It made no threats; it simply told the story.

The Society could well rely on the support of public sentiment if the public felt convinced that the bill of complaint issued from a reliable chancery. As a result, the phosphate mines were obliged to shut down, and a repetition of the abuse has so far been prevented.

A more difficult task presented itself in the complaints of Italians in West Virginia. There the circumstances were such that no fair opinion could be formed regarding the alleged abuses without an investigation on the spot. So the Society *eat one of its officers with an assistant, to study the conditions of the labor camps in that State_ from which complaints had come.

Many were the difficulties and hardships encountered in obtaining evidence against those who had abused the complainants. But there was an inspiring .element in the work begotten of the thought that a small but determined band of American philanthropists, hundreds of miles away, had sent their representative to these desolate camps to maintain the principle that, even if men are not born equal, even though strangers in blood, they are born free. And here freedom was denied.

There were shocking instances of men forced to work under armed surveillance, their baggage searched lest they might use arms to assert their inalienable rights as free men. Laborers were tied and bound, boys and men brutally treated, cursed, beaten, and kicked. I need not dwell here on the specific instances of cruelty and abuse, nor on the causes of such lawless conditions, most of which I have elsewhere set forth. Besides, they make unpleasant reading, showing the supineness and indifference of the constituted authorities in enforcing the laws.

I would rather dwell on some of the lighter scenes, for the dark picture had its bright side. It was something very novel to notice the surprise among officials and contractors at the idea that an American society should be taking so much trouble for a few " dago" shovelers. The moral effect of this fact alone was worth all the money and labor contributed by the Society.

The Italian laborers themselves could not quite understand the situation. They naturally looked upon us with suspicion; their experience of Americans having been gathered from their contact with careless or brutal foremen and bosses, they could hardly have faith in disinterested Americanism.

When finally their suspicions were allayed, they persisted in looking upon us as persons invested with official powers, government officers who should have worn badges or gold braid. They could not conceive of private citizens arraying themselves against those whom they feared, and who to them represented power and its abuse.

I have no doubt we made a ridiculous figure in those wild places, carrying the habiliments of civilization; and yet, if we had roughed it as to dress, if we had omitted collars and cuffs and gloves, and had worn comfortable knock about hats, we would have failed to win the confidence of the men. Small as it may seem, the observance of such minor matters was of the very greatest help.

Going among these Italian laborers as representatives of an American society was an object-lesson to us of the power of friendliness as an assimilative force with these foreigners. As soon as they knew our purpose their native courtesy came to the front, and it mattered nothing that the giving of testimony meant a possibility of harm to them; they became zealous and intelligent assistants.

In a rough country they chose their best fellows as night escorts to us; they even mounted guard over our shanty. They traced up witnesses, and sifted their own testimony to give us only the most reliable. Their humble meals and their poor shanties were offered to us with simple, unaffected, yet dignified hospitality.

Within a month of the beginning of the investigation the Society was apprising the country, through the National press, of the bad conditions in West Virginia. Its only great weapon was publicity.

West Virginia herself was made aware of her shame. Its Chief Executive, its Labor Commissioner, and its press urged action, even though admitting the difficulty of reform through the inefficiency of the local authorities. But this was not enough; contractors who are so unbusinesslike, if not brutal, as to maltreat their men, are not the kind to be influenced by public opinion.

Against them the Society was forced to harsh measures, even though these, of necessity, affected the good and bad contractors alike. It published the facts in the Italian press throughout the country; it fearlessly gave the names and addresses both of the Italian padrones who were sending laborers to West Virginia under false promises and of the American contractors who had abused their men.

This had the expected effect of preventing Italian laborers from going to West Virginia—a heavy blow to those contractors who had time contracts on their hands (and they are many), and who needed men greatly. Contractors there are now offering special inducements, but Italians will not go.

There is what seems to me an important lesson to be learned as regards the function of immigrant societies, if we wish to make them instruments for the assimilation of those countless people who are flocking to us, They should, first of all, lose their distinctive foreign character, and take on their directive boards enough native Americans to bring these in touch with the characteristics of the incoming foreigners.

In the second place, they should enlarge their work from that of immediate assistance to the landing immigrant to the wider field of protection as practiced by the Society for the Protection of Immigrants—a protection rendered not as of Germans to Germans, or Jews to Jews, or Swedes to Swedes, but as men to men, as friends to fellows.

There is probably no greater enemy to the ready assimilation of these foreigners than the ballot-box. This may seem to be contrary to the accepted opinion, but do the facts justify the prevailing opinion? You have the German vote and the Irish vote, and the way of winning the support of either is to put up men representing those nations. The politicians favor such a system because the " foreign " vote can thus be handled better. But it is obvious that such a system tends to perpetuate race distinctions and to prevent assimilation.

We ourselves are mostly to blame; the foreign-born stump speaker is justified in urging his hearers to unite "as Italians " and vote for " an Italian," in order to uphold their rights and obtain favors. There seems no recognition possible except through the threat of the ballot-box of a united foreign vote.

The way out seems to me to lie in approaching the immigration problem from the point of friendliness rather than of defense. That is, in doing things that will tend to make the foreigner feel that he is among friends. Assimilation is a mutual process; it depends for success not only on what the foreign body will do to be absorbed into the greater body, but upon what the greater body will do to attract it.

Ours may be the best government on earth, our social life best type of a democracy, our State the most promising field for opportunities for fortune and success. But we take it too much for granted that these are such obvious facts that they must appeal directly and clearly to the foreigners who come to us. As a matter of fact, however, they do not, because, unfortunately, the foreigner too often sees the worst element of Americanism and comes in contact with only the seamy side of our National life. It is no pleasure to be looked upon as a " problem," still less as a "menace," yet this is what we often make the immigrant feel.

Take the Italian, who is probably the most sensitive to impressions among those who come to us. His children make good students in bur public schools, for they are bright boys; but many more would attend if they did not have to face the stigma placed upon them by their classmates, who look down upon them as " dagoes."

The press would help us in the work of Americanizing them, but why should Italians read American newspapers which chronicle only their crimes as distinctively Italian products and never take an interest in the good work they are quietly doing? And so Italians support a cheap Italian press, which helps only in keeping them apart from their American brothers.

There should be no " German Hospital," no "Italian Savings Bank," no "French Benevolent Society;" in short, no such marked lines of race distinction as we have. Nor will there be if we appreciate that if we really want to solve the immigration problem, if we are really anxious to strengthen the Republic and 'assure its honorable future by assimilating the foreign-born element in it, we must strive to know the characteristics of these people and their possibilities for good, in the light of their history at home.

Then, knowing them, we can approach them and win their confidence and friendship. That this can be done is shown in an eminently practical degree by what the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants has done in less than two years, by Americans who knew little, if anything, of immigration work, with little money at their command and still less moral support to aid them. But it was work in the right direction, and it counted; it was, above all, personal service.

Let us have less talk and discussion, and more active and organized effort; .fewer editorials on the " educational test" in the immigration law, and more educational institutions for our immigrants of the type of the Children's Aid Society School in Leonard Street, New York; less oratory on the dangers of the foreign peril, and more active friendliness for those who, directly or indirectly, have contributed to our material greatness as a Nation, and who, rightly helped, will contribute to our intellectual preeminence as a people.

Speranza, Gino Carlo, "Solving the Immigration Problem," in The Outlook, Volume 76, No. 16, April 16, 1904, pp. 928-933