Flirtatious Fashions for Women - April 1919

She who thinks fashions are dull should not skim the surface of the pot but dip deep down into its boiling contents to find the swirling ingredients that are awaiting their chance to pop out.

Fashion was never dull, except on the surface, and today it is inextricably mixed with politics, history, psychology, and industry. Paris is not the only spot around which the boiling current swirls. America has proclaimed her second Declaration of Independence.

This phrase should not be misunderstood by those who flaunt the eagle and cry aloud for the supremacy of God's country; it only means that we do not slavishly follow Paris, and I fancy that Paris admires this trait in us.

Our most rebellious act was to introduce the long skirt when the French launched the short one, and with a stubborn obstinacy we clung to our own opinion and appeared to have no intention of changing it.

Our independence has been further shown in the introduction of new colors, individual combinations of fabrics, and a new-born spirit of confidence; nor have we yet adopted the French four-inch sleeve for day gowns.

In other words, we are like the tiny child standing on its own feet in the middle of the floor for the first time, not fearing to fall.

There are students of dress who think that the American Declaration of Independence has produced a sudden, rapid boiling of the fashion-pot and that it is the reason for the extraordinary mixture of clothes that Paris has thrown into the market for two years. She has tried to please the American public through the American buyers.

Possibly, though not probably, this theory is correct. The genuine truth is more likely to be that Paris needs a group of leaders in fashion. Her dressmakers have always thrown out dozens of various styles, silhouettes and color combinations, and she had offered these to her influential directors of style and fashion before the world had a chance at them.

These women were made up of a small clique in aristocratic circles, a larger clique from the stage, and still another, and a powerful one, from those who walk the primrose path. It was these women who cast aside the things that were not to be. They wore the clothes of their own choice, and the world followed them.

These clothes were showing at the semi-annual exhibitions to the other countries.

Now Paris has not had a set of leaders since August 1914. However, she may find herself committed to her old ways by the summer, for there are rumors of renewal of those features of the good life where exploited fashions are in the limelight.

If the old leaders arise, Paris will again submit to their verdict.

In America, there has never been a set of leaders, except in finance. In dress, as in society, no one person or group of persons has had the ambition, or perhaps the power, to dominate the activities and the clothes of other people.

This condition makes for individuality in dress, but it also makes for chaos, and chaos is the word that describes the present situation of fashionable apparel. In the clothes of today, we are heirs to all the ages.

She did not insist upon any particular silhouette When Paris sent her models to this country in March. She drew her inspirations from so many historical sources that if all her mannequins had appeared together, they would have staged a fancy-dress ball.

When the American clothes appeared on the scene, and very, very good clothes they were, they, too, dashed backward and forwards through several essential epochs of history.

Clothes from the period of the Stuarts were cheek by jowl with those from ancient Japan, modern China; the Arizona Indians and the artificial Eighteenth Century hobnobbed pleasantly.

Two Silhouettes—and a Third

It wouldn't matter much if the details in seasonal clothes were chaotic, but women have been confused because the silhouette has not been definite.

Two dominating contours ruled until April, that of the Directoire and that of the Japanese. The former was not a direct contrast to the straight lines that we have adopted for two years, but the Japanese posture was striking, peculiar, sometimes uncanny.

It gained in momentum as the weeks went on, and today its only rival is the third silhouette, which has been advanced by two influential designers, one in Paris, one in America.

This is the Dutch-doll silhouette, or as Callot calls it, the Camargo style, a name which is more euphonious and distinguished. The waist is tight and wrinkled, the skirt is voluminous, and the difference between it and the full skirt of other periods is that the new one has a tight hem.

With these three silhouettes out in the open it is no wonder that women are confused. Must they accept one, both, or all of them? Which is French, and which is American?

Which will endure, and which will pass away? Do they wish to appear like Geraldine Farrar in "Madam Butterfly," as Madame Tallien of the Directoire, or as a Watteau shepherdess?

Women are conscious that all three silhouettes are struggling for supremacy, yet the average American woman wants to get into the picture, but fears to feel herself out of it in six weeks.

She is a canny person, the average American woman. She is not as avaricious of her money as of her time. She is ceaselessly restless, and she imagines that she is the center of a world of activities, even though she could indulge in limitless leisure without injuring herself or others.

Therefore she dislikes a suggestion of continually changing in her clothes. This is the attitude of the average woman.

Out of this attitude of mind has grown the custom indulged in by many women of wealth and fashion, of ordering a half dozen gowns on one model. If a woman does that today, she is foolish, for the situation in dress is as unsettled as the political situation in the Balkans.

Running True to History

The American woman rarely looks backward, but if she did this today, she would find that the extraordinary chaos which exists in fashions in this country and Paris has had its parallel in all stupendous wars.

There is always the period of self-abnegation in clothes, expressed by a chaste severity of line, ugly or lovely; then a period of relief from death and terror, in which the pendulum swings wildly to the other extreme and produces a violent reaction that expresses itself in rudeness which often lapses into indecency; then chaos, when the struggle against rudeness arises, which eternally resolves itself into a flirtatious upsurge.

We have been through three of these phases since August 1914, and the fourth and last phase we enter now. Frivolity, in utility and over-decoration, is the quality of flirtations in a dress.

It will be interesting to watch the development to find out if years of artistic endeavor have carried us beyond the ugly periods of coquettish costumery.

The main thing is that a woman is again to be seductive. Historically, she has always tried the old and ancient art after being repressed through terror.

Those who study history in its relation to women's dress saw all these phases coming after the war was well on its way.

Eddie Rickenbacker, the American aviator, in telling how high one of his machines went, said that he could see the sunrise day after tomorrow. That is what some of the prophets of dress saw two years ago.

It is now "the day after tomorrow." The prophets were not quite sure what form of flirtation the dress would take. Today they find out. Its expression at present lies between the Japanese and the French woman of the Eighteenth Century, who repeated herself in the middle of the nineteenth.

The flirtatiousness of the Japanese silhouette is as old as time. Its birth was the birth of dress, the day when a woman covered herself for seductiveness. However, the last development of the Japanese idea is astonishing to all observers.

To see Geraldine Farrar in the gorgeous robes and slinking attitude of Madam Butterfly is no longer to see alien costumery, but the apotheosis of the clothes and posture of an ultra-modern woman.

The source of this inspiration is said to be the presence at the Peace Conference of the Japanese delegation. So enamored of the fashion are some of the individualists abroad that they paint the eyes into an oblique line and brush back the hair with brilliantine that suggests lacquer.

Everyone whose hair grows to a point in the middle of the forehead exploits it as a precious jewel.

The women in America adopted the Japanese posture months ago. It came out through the mannequins in the salons of the smart dressmakers, a class of young women from whom America gets many of its dominating fashions.

The stage, eager to seize anything that promises more posturing, more or less successful, accentuated that peculiar swing backward that shows off with such nicety the slenderness of the figure.

So the young and the graceful aped the stage and the mannequins. In consequence, the very dancing steps had to be changed to suit the modern frock and the tilt of the body.

It is as curious in its way as the famous Grecian bend that has the privilege of dropping downwards through the corridors of history.

It is not possible for this attitude to outlast the season if the new silhouette prevails. If we are to appear as Watteau women, we resume the upright in stature.

The doctors and physical culturists will be joyful. It will be interesting to observe the modern woman fit herself into the clothes of coquetry. None of her observers’ will despair of her ability to do it well and with abounding grace.

She has proved herself capable of assuming, even if she does not possess, the qualities of a chameleon; she goes to robustness from emaciation, and back again whenever Fashion puts over a new silhouette.

She is now asked to swing from the military correctness of figure to one that snoops and slinks, or one that has the swaying movements of an upright lily, a lily that never was on land or sea, one that must smile and retreat and allure, if it is to live up to its apparel.

Why all this change, asks the wondering world? For the sake of war-weary men, is the answer.

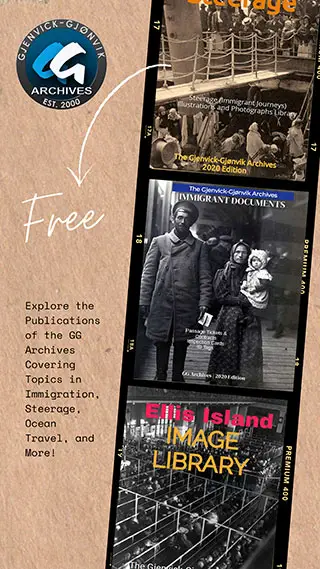

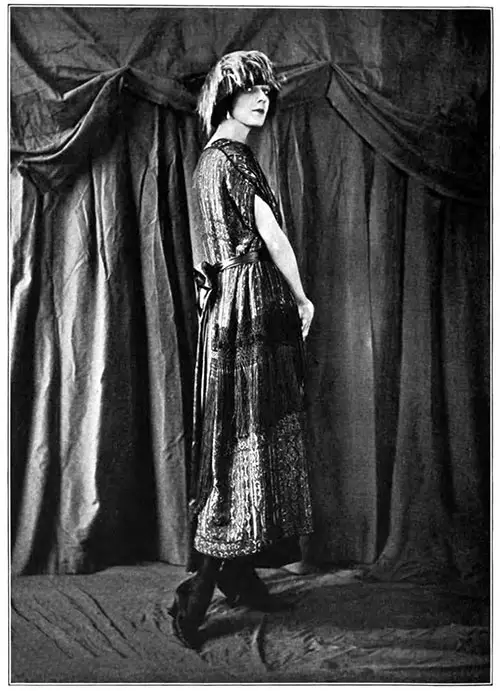

Afternoon Gown in Taupe and Gold Embroidered Chiffon by Callot Posed by Mme. Lubovska

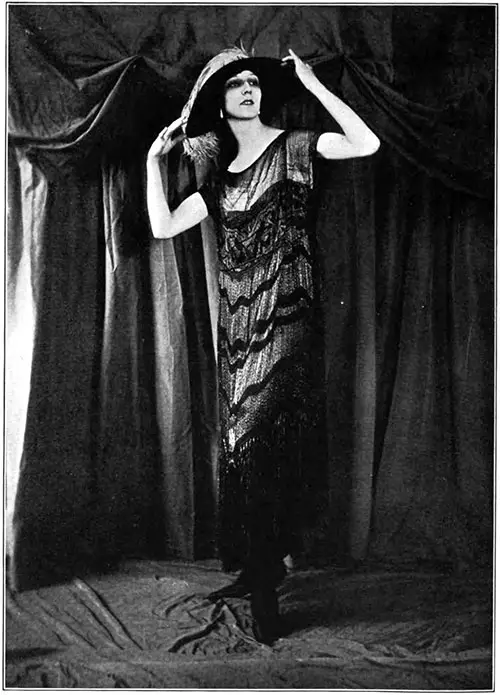

Parchment Charmeuse Evening Gown by Hickson Posed by Mme. Lubovska

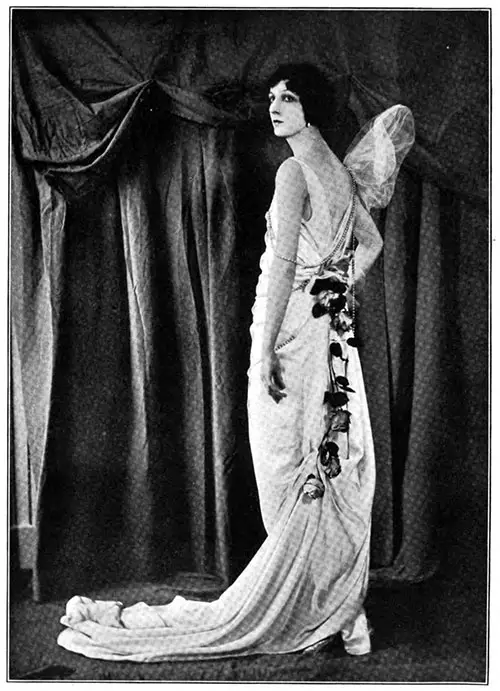

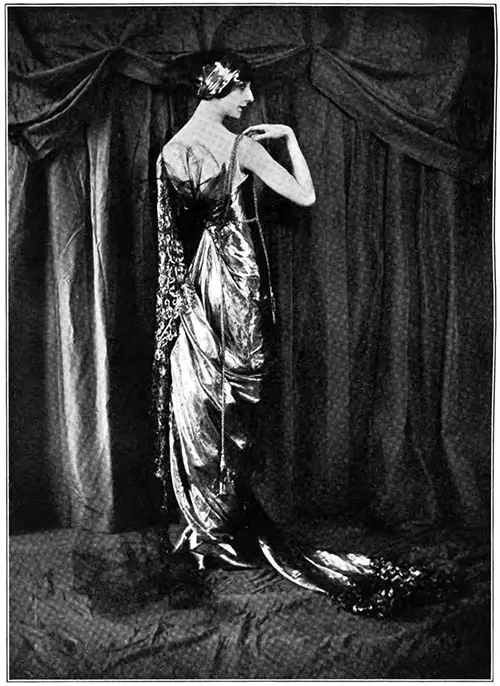

Evening Gown by Bergdorf-Goodman, of Havana Brown Charmeuse, The Draping of Which Serves as The Only Trimming Except For The Girdle of Jade Green and Amber Beads

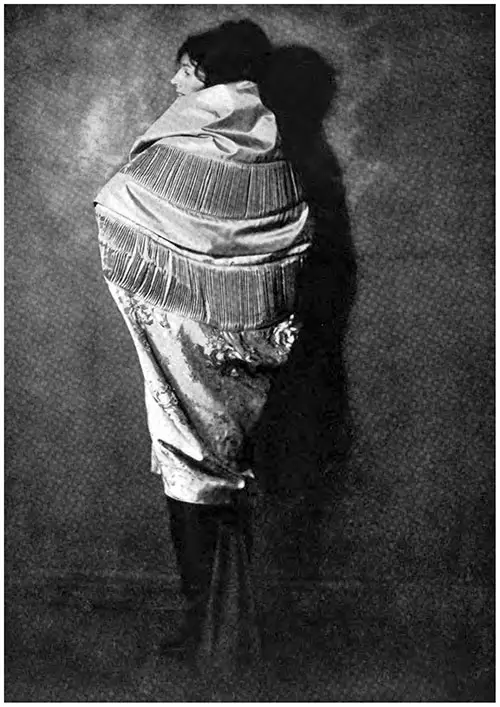

This Distinctive Wrap, Designed by Bergdorf-Goodman, Is of Apricot Brocade and Taffeta

Afternoon Gown in Blue and Silver Brocade by Callot Posed by Mme. Lubovska

Evening Gown in Cloth of Gold, Showing A New Use for Paradise in The Corsage. By Hickson Posed by Mme. Lubovska

Rittenhouse, Anne (Miss Harrydele Hallmark), “The Lotus Leaf: The Glass of Fashion - The Recrudescence of Coquetry” in The Lotus Magazine, New York: The Lotus Magazine Foundation, Inc., Vol. X, No. 4, April 1919, p. 219-231.

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.