London Fashions June 1888

une is the month of fruition; our flowers and our dresses are seen at their best. We expect sunshine, and we generally enjoy it, so that everything is seen en couleur de rose.

The tint of the year is green; no undecided green that melts into blue, but the emerald and watercress tint that is really becoming. It asserts itself mostly in millinery and green tulle bonnets trimmed with deep green velvet with water-lilies at the top, which are seen at most fashionable gatherings.

Time was when ladies did not wear hats in town; now young girls hardly sport anything else, and some married women only put on a bonnet when the occasion absolutely demands it. Doubtless, it is on this account that so many are stringless and so approach nearly to the hat.

They are shaped somewhat like a round tent, the flowers forming a point on the top of the head and whether it be loops of velvet or ribbon, they all start from this apex. In hand, these bonnets look extremely small; not so on the head, where their adornments give them height.

Floral bonnets are being prepared for Ascot and other peeps of Vanity Fair. Some of them are entirely composed of small blooms clustered together on a wired shape with an upstanding bouquet at the side; newer and more original are bonnets composed of one single flower such as a large rose or a peony.

Resting on the head are large velvet pink leaves set in a circular form, and above them, silk leaves (smaller, and of a slightly lighter tone), crowned with a tuft of rose-buds. There is nothing bizarre in this headgear; on the contrary, it is eminently becoming.

Another of the same class of bonnet is composed of moss-green velvet leaves, surmounted by a bunch of lilacs and most natural mignonette.

These styles of head-gear accord well with the floral parasols, surmounted by a rose as large as an ordinary cabbage, and bordered by rose - leaves made of Lisse.

The groundwork of these parasols varies greatly, from velvet to the most transparent piece-lace, and they display a variety of flowers, which sometimes are used in bunches as a trimming, and sometimes constitute the parasol itself, the upper part forming the heart of the flower, the lower portion the petals.

The idea is poetical and suited to a summer day. The size is not quite so large as the parasols of last season. En-tout-cas are most used for everyday wear and red more than any other tone. They have long cane handles with gold tops, and serve a double purpose, being used as walking-sticks.

Of course, you know that a woman of fashion requires a cane in this year of grace 1888 quite as much as the beaux of a century back. A glance at our illustration of a Race Course Costume (below) shows how she uses it, as also the latest cut of Directoire bodice with its elongated waistcoat, introduced by Messrs. Lewis and Allenby.

Next to green, red is the favorite color. Red cotton gowns will be worn, and red bonnets. Red tulles, by a strange perversity of taste, are covered often with red beetles, which inspire an inclination to shake them off, and so to get rid of a foreign and an undesirable ornament.

Americans call all insects of the kind "bugs," and, notwithstanding the unpleasant association, they are buying bonnets mainly, with a beetle of some species used as trimming.

There is a great disposition to show the hair through the headgears, which are sometimes cloven down the center from the forehead to the nape of the neck, while others have fronts composed of detached bands of jet.

Jet is the one favorite material, and, trimmed with mixed flowers, assimilates with most dresses. The brims of many linnets are edged with jet ruches, or with silk pinked ruches of two tones.

The strings are sometimes made of lace, sometimes of narrow velvet, and start from the middle of the back, without being attached at all to the sides.

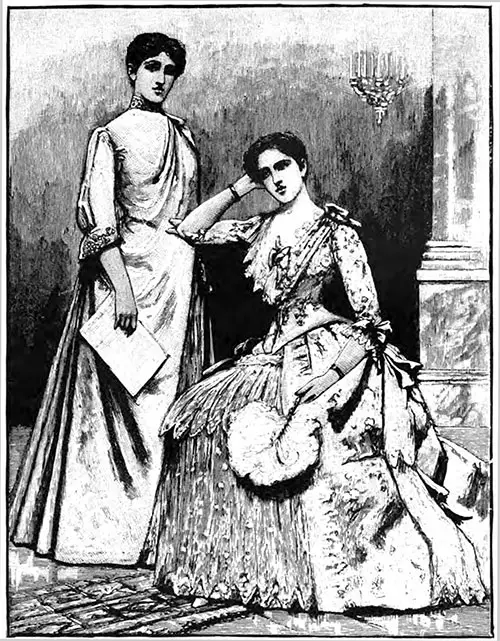

The printed surahs and toiles de soie, which, after all, are a revival of the useful foulards, are being employed for tea-gowns, and in our first illustration, an easy mode of making is shown.

Tea-Gown of Printed Surah, with Embroidered Collar. Dinner-Dress of Pompadour Broché, with Cream Lace Flounces, of Printed Surah, with Embroidered Collar. Dinner-Dress of Pompadour Broché, with Cream Lace Flounces.

The dress is cut in one, and the front breadth fastens on the left shoulder, the collar being embroidered, also the cuffs. The sleeve is new, easy, and comfortable, coming below the elbow.

It is just the kind of dress which could be worn without stays, as tea-gowns all originally were; or it can be made dressy enough for home dinners. On a hot summer day, it could be slipped on comfortably after a long walk or drive.

Dressmakers are directing more attention to tea-gowns than to almost any other style of dress; the demand is so high.

While some of these garments are made of striped moire and velvet, in the new cowslip-green (a perfect color for candle-light and day wear), to fit the figure exactly with the bodice cut open in front; others are concocted of house flannel or simple mousseline de laine which is printed with floral sprays and is fresh and well suited to youth.

The back should flow easily, and the front is generally loose, often made with wing-like sleeves of some thin material.

The accompanying figure (above) wears a dinner-gown of Pompadour broché, made to rest on the ground. It has the appearance of being a lace skirt, with a silk one over it. You see the double flounce of vandyked lace in the front, and again at the side, where the silk opens to show it. The bodice has each shoulder differently trimmed.

The fronts of evening gowns are the medium for displaying most elaborate materials and minute ornamentation. Much of the wide lace intended for them is really an embroidered net, into which are interwoven bands of gold, mixed with white silk, which softens it while it gives it substance.

Many of the striped nets have hand-painted flowers in natural colorings between, or sometimes the sprays are worked in silks. For tea-gowns, they are made sufficiently long to form a blouse to the bodice.

The Directoire style suggests the best silk embroideries arranged to form the fronts of the more costly gowns. They always have an important design at the foot, which is often simply accompanied by distinct sprays above. Large sheaves of straw are set on a rich white poult de soie, the designs bordered with fine gold cord, and detached wheat-ears sparsely scattered all over.

Crepe de Chine is worked with true lover's knots in gold, enclosing garlands of Pompadour roses. Moires have the watering outlined with spangles, intermixed with sprays of grass and wheat, and many conventional patterns of the Pompeian order are finely wrought.

Stomacher pieces accompany such work for the bodices. Tinsel threads are used for floral bouquets on net and silk and play a most important part in the guipure galons, recalling the play of tints in mother-of-pearl or opal, "like colors of a shell, which keeps the wear and polish of the wave."

The colors are good in themselves but rarely has Dame Fashion blended them so deftly.

Mme. Renande of Sussex Place, South Kensington, has a number of beautiful stuff from which dinner and tea-gowns are made in original and pretty combinations, such as yellow and coral-pink (both light and delicate) and heliotropes of two tones.

The lisses and crepes de Chine are some embroidered, some interwoven with a diagonal insertion of lace to suit matrons, while the grenadines in all colors make young girls' gowns, and are especially well suited to summer dinner dresses, which have to stand the daylight. They are looped up with bunches of ribbons in girl-like fashion.

Reception Dress

The redingotes made by Mme. Renande are a useful and elegant style of dress, which can be either simple or elaborate. The skirts are made of plain wool or shot silk, and the redingote reaches almost to the hem, has wide velvet revers, and square pockets, cuffs, and collars, the back being arranged in large folds.

The addition of tinsel galons makes an elaborate dress, though a fancy and plain woolen combined answers every purpose.

Opera-cloaks go through various phases from time to time, and just now they are elaborate and bright in coloring, some of the brocades being outlined with gold, and the satins are embroidered all over with floral sprays.

Mme. Renande has brought out a new shape, short at the back, the square fronts pleated and falling low on the dress. The fronts and backs are united by a straight basque like a Directoire pocket, and large gimp ornaments of a combination of all the colors in the stuff appear in front, on the shoulders, and at the back.

"You may wear your rue with a difference." Indeed, opinions differ widely as to the depth of mourning necessary to show respect to the departed. However, in our more enlightened time, people are beginning to see that it is no proof of woe to shroud themselves in perishable silk crape, which spoils with every shower and soon looks shabby.

Messrs. Briggs, Priestly, and Sons have conferred a public benefit by introducing some silk and wool crepe cloths (forty-four inches wide, soft, and firm) with all the mournful appearance of crape. These are calculated to bear the wear and tear of constant use.

Wool crepe cloth is even stronger; and there is a thicker make with large patterned crapings, intended for cloaks, and useful for the deepest garb of woe.

For summer and dinner wear there are three qualities of wool grenadine, two of them as thin as barège; and the pure white veiling, with black ribbons, could be worn as the depth of mourning lessened.

For first mourning, there is Melrose cloth (which has a fine interwoven pattern like a thick make of silk called widows' silk), silk and wool Henrietta cloth, and silk and wool Armure cloth. The combination is one which deserves special attention.

Black and greys and lavenders are so generally worn now, that it is not easy to find an excellent half-mourning material; but some pepper-and-salt grey and black stuff of the same firm in silk and wool exactly meet the want.

Some are fancy-woven, and some are plain, but all display a streaky admixture of tones which children call " thunder and lightning." Also, there can be no doubt as to why they are worn; no one would select them except for mourning.

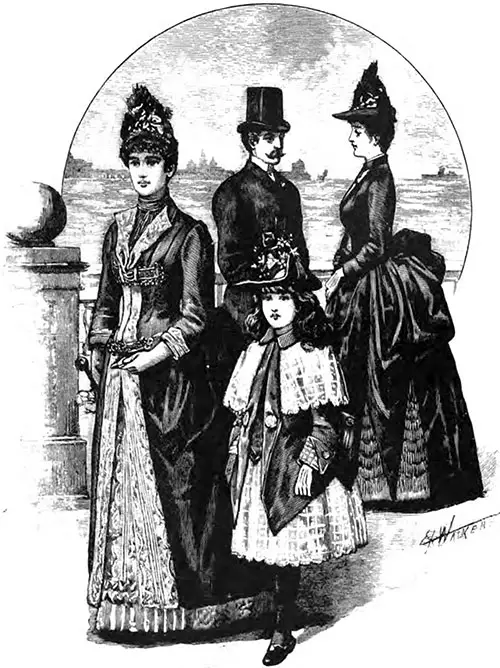

Promenade Costumes

The group before us gives a true impression of the dresses now worn out of doors. In the prominent figure, the bonnet is stringless; the wired ribbon combined with flowers makes it stand up high over the face. The dress is of two colorings.

The plain petticoat has a flounce with a double heading and is of the lighter tone, which also borders the redingote, forming revers in the front of the skirt and bodice. A gathered vest with collar appears beneath the turned-back portion.

At the back the skirt is sewn in large pleats to the point of the bodice, and essential metal ornaments of mixed coloring fasten the revers on the bust and at the waist: a new treatment which opens out an admirable use for the old clasps of antique design, that used to be worn years ago, and are still existing.

The little girl wears a hat that is turned up only on one side but with a sharp and very decided corner covered with velvet. Flowers entirely hide the crown, now a prevailing style, the straw or velvet, of which the rest of the hat is made, being superseded by a transparent foundation.

It is a healthy mode, as it lessens the weight. The dress is a mixture of finely embroidered muslin and silk; the skirt is full and gathered, as is the muslin cape. The silk is cut after the order of a Louis XV jacket; only it is caught up at the side.

It turns back in front to show a contrasting lining, fastened with one large button, the cuff showing a corresponding button and the same coloring. Beneath these is a vest, which ends below the waist in a point. The idea and the mode of carrying it out are quite new.

The young girl standing behind the child wears a dress in which the idea of one gown over another is again apparent; as it is in most of this season's dresses, though it has many developments.

Here the under-skirt can be composed of lace flounces, plain or goffered, the over-dress being draped in points above it.

It is a polonaise, and might well be adapted to washing-gowns, though these are now mostly made with full sleeves gathered into a band, hidden by an upturning cuff, or showing many runnings, on which a round lace, like a bootlace, is sewn, the accompanying tags being allowed to hang.

The gatherings are often repeated on the outside of the arm, below the shoulder, and in the middle of the length.

Full bodices with belts are essentially well suited to cotton, but it is more fashionable now to carry the fullness down to the long point which comes below the waist, and to trim the bodice with one or two revers of a contrasting color, often covered with lace.

The draperies are always long, the back being arranged full, and sewn around the point. At the side the skirts frequently open to show a series of scanty flounces trimmed with lace, which is laid on, and not sewn, at the edge.

Polonaises are a distinguishing feature in washing gowns, and in the pure mousseline de laine, with tiny esprit spots, such as red on a cream ground, or white on a red ground. The polonaises are long almost enough to hide the under-skirt; this is full and plain.

The trimmings on bodices—such as ribbon or bands of embroidery or lace—start from beneath the arm-pits and meet in the center of the front, which is becoming to the figure, and quite an original treatment.

Wide sash ribbons are often placed in the same way with another broad sash, an arrangement nearly always seen in the Directoire styles. The double sash seems to swathe the waist, and — if adequately arranged—diminishes its apparent size.

There are two new materials for simple summer dresses —such as, "mousseline chiffon" (like fine undressed Mull muslin), which, by means of a cool iron, will keep in good order a long time, and is to be had in all colors; and "crepon Pekin," which is more costly.

Race Course Costume

The latter makes beautiful dresses by itself, or is applied to the fronts only, and might replace the lace in the reception dress of our second picture. It shows a silky stripe of uniform tone matching the groundwork, made of a tenacious thread, yet so soft it might be passed through a wedding ring. Race-gowns made of it would have parasols to match.

Stripes display an infinite variety. The striped moire, with its bouquets, is used for the back of the reception dress (above).

Johnstone, Violette, “June Fashions,” in The Woman’s World, Cassell & Company, Limited, London, Paris, New York & Melbourne, Volume I, No. 8, June 1888, p. 377-380.

Note: We have edited this text to correct grammatical errors and improve word choice to clarify the article for today’s readers. Changes made are typically minor, and we often left passive text “as is.” Those who need to quote the article directly should verify any changes by reviewing the original material.