Disease Quarantine of Inbound Vessels

Barriers Against Invisible Foes. Frank Leslies Popular Monthly, June 1892. GGA Image ID # 14ffe81782

" Quarantine for the protection of the public health, according to the provisions of this Act, is hereby authorized & required and established in and for the port of New York, for all vessels, their crews, passengers. equipage, cargoes. and other property, on board the same, arriving thereat from other ports."—Act of April 29th, 1863, Section 1.

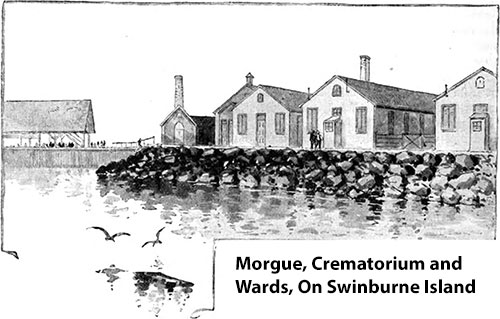

IT is a pleasant morning in late summer. The sun shines warm and bright over the group of buildings and chicks lying a little above Fort Wadsworth on the east shore of Staten Island, and known as Sthe Quarantine Station. Its rays are made bearable by a refreshing breeze that blows inland over the bay. Still, it is warm enough to make things appear quiet and sleepy.

In the lower room of the little building at the land end of the L-shaped dock, some boatmen are lazily waiting for incoming ships, while another is tinkering about in a little place in the back, fitted up as a workshop.

In the smaller, towerlike second story the telegraph operator of the Western Union is kept busy, besides his routine work, in receiving and transmitting messages coming in from Fire Island, the Highlands and Sandy Hook. from which places the arrival of ships is successively reported for the benefit of the public.

On two sides of his den long, narrow openings are arranged in the wall, through which the operator thrusts his telescope, by the aid of which he verifies the names of the ships as they pass him and perhaps other details occasionally.

But the watchers in the room below have seen a large steamer coming in, and the big bell that hangs suspended on a forked pole before the door is vigorously tolled. The signal is intended for the doctors that live in the two houses perched picturesquely between the trees higher up from the shore.

Boarding Incoming Steamships

Vessels are boarded as soon as possible after arrival, and thus, only a few minutes later, a blue-uniformed figure comes hurrying down the wooden flights of steps which lead from the offices and dwellings to the dock. It is one of the two deputies that assist the Chief Health Officer, and to whom falls a good share of the outside, routine work.

That there is plenty of this is apparent from the latest report of the Health Officer, from which it appears that 5,758 vessels from foreign ports, and 1,842 from domestic ports, arrived and were inspected at Quarantine during 1890, the passenger steamers bringing over 370,000 steerage passengers.

The George A. Preston Tugboat

Beside the dock lies the tugboat of the station, the George A. Preston, with the official yellow flag fluttering at its stern. (Yellow, by the way, gruesomely suggestive of that dread fever from the South, is the official color of Quarantine.) The captain is already at his place in the wheelhouse, and as soon as the doctor and the Associated Press agent get on board, off they go.

They have already put in two hours of hard work in the early morning, and there is more before them, for away down the bay there are a number of black dots that are rapidly resolving themselves into incoming ships, among them one of those huge transatlantic ferryboats. The little steamboat puffs and reels as it makes straight for the first arrival, a Scandinavian freight steamer.

As we near it, the men begin to tumble up on deck from all points, and by the time we make fast to the vessel's side, and the doctor reaches the ship's ladder with a long jump and clambers up they are drawn in line ready for inspection. The crew that stands before the officer is composed principally of descendants of those hardy Norsemen who " discovered" America on their own hook ages ago.

A Bill of Health

Everything is found in good order, and the bill of health is banded over, together with the regular fee of O. (All masters of ships from foreign ports must present such a bill of health, duly executed by the consul, vice consul, or other consular officials of the United States at such port, setting forth the sanitary condition and history of the vessel.)

Morgue, Crematorium, And Wards On Swinburne Island. Frank Leslie's Popular Magazine, June 1892. GGA Image ID # 14fff9a78f

A similarly satisfactory state of affairs prevails on the next ship, a West Indian freight steamer, except that there is an uncertified bale of skins on board, and the word is passed to the captain of the tug for the necessary disinfectants. A blue-coated boatman hustles up the ladder with a huge black bottle. It contains oil of vitriol, a little of which is mixed in a pail with some other chemicals, placed beside the bale and covered.

A good whiff of the strong vapor that arises from this mixture is enough to take your breath away, and the steaming disinfectant thoroughly permeates the entire bale. Oil of vitriol or sulphuric acid is generally used to disinfect all animal products not vouched for by certificate as having come from healthy animals, or which have been shipped from a point infected by some epidemic.

Disinfecting A Ship

If there is a case of infectious disease, like smallpox, on board, the most potent disinfectant, sulfur, is used in the room occupied by the patient. Chlorine gas is employed in regular fumigation, while for cholera and yellow fever a strong solution of bichloride of mercury is used.

Quarantine

Quarantine, by the way, used to apply only against yellow fever, cholera, typhus or ship fever, smallpox, and "any new disease of a contagious, infectious or pestilential nature." However, by Act of Legislature of 1885, scarlatina, diphtheria, measles and relapsing fever have been added to the diseases subject to quarantine at the port of New York.

Meanwhile, other ships have been arriving, and are awaiting their turn in a long, straggling line. They are taken up as nearly as possible in the order of their arrival. The little tug turns on its center and steams a short distance to where the large passenger steamer which we saw coming up before is now lying; the vessel is one of the Hamburg Line.

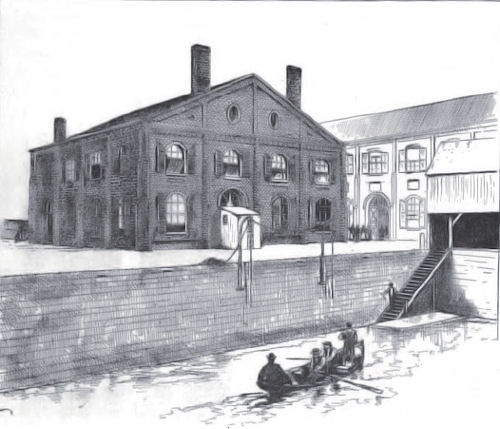

Telegraph Office and Quarantine Boathouse. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, June 1892. GGA Image ID # 1500059b6c

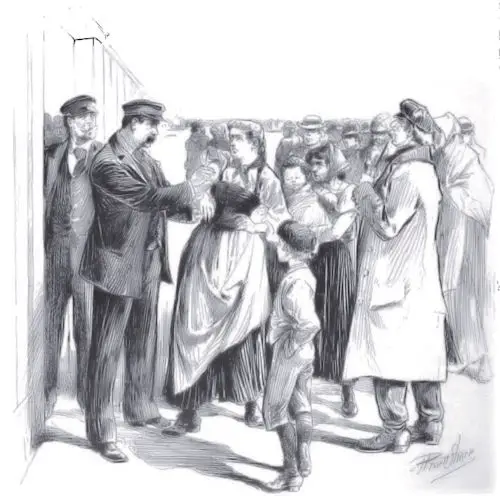

As we near the floating palace, we diner% the officers standing in a group in the center of the ship, a fine-looking body of men, broad-shouldered, well-built Teutons. The cabin passengers are gathered together aft, divided off by a rope stretched across from side to side, while the forward deck is black with the mass of steerage passengers, 350 in number.

A few minutes later the latter are passing in single file before the Health Officer, those who forget to uncover their heads being quickly reminded of the fact by the energetic "Hal 61" of the ship's officers. Each one holds up his green ticket, which furnishes evidence of his vaccination by the ship's surgeon, and which he will also need on some of the emigrant trains going West.

What a heterogeneous stream of humanity passes before us! Germans from all parts of the empire; Austrians, their trousers thrust into high boots, shiny and smooth except for the accordion-like wrinkles at the bottom, over the feet; Russian and Polish Jews, the men usually wearing very long and heavy coats and an apologetic air, with strings of children, carried, dragged and stumbling along; Arabs, Italians, and what not, most of them with a half-scared, furtive air, which some make an unsuccessful attempt to conceal under an assumption of bravado or jocularity.

It is surprising what a large percentage of the people consists of Germans of the better classes, many of them evidently well educated, forced for reasons of economy to avail themselves of the cheapest mode of traveling to the promised land of the thousands who hope to better their condition.

But the inspection is over, and the officious little steamer again turns in its tracks and makes straight for a large sailing vessel that has cast anchor nearer shore. This ship is from Rotterdam. The usual questions are put and answered satisfactorily: the captain's name, the duration of the voyage, the number of men, what cargo, the consignee's name, and the broker's name.

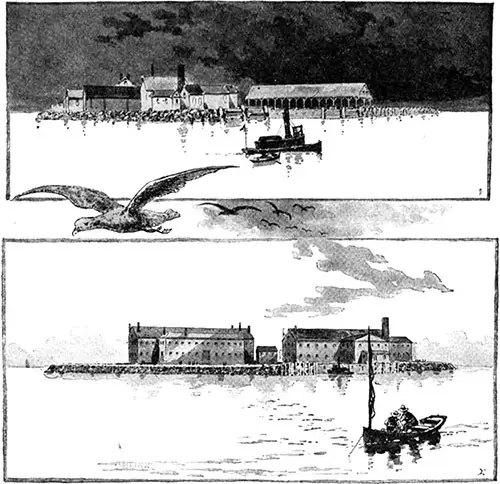

Swinburne Island (top) And Hoffman Island (bottom). Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, June 1892. GGA Image ID # 1500022e03

The skipper is unprovided with a bill of health, however, which omission makes a difference of $3 to him. On the other side he could have procured it for *2; here it costs him O. Again the tug swerves off, and a few minutes later we are lying beside a magnificent four-master. It has come from the Philippine Islands, and the sailors form a crew made up of a medley mixture of slight Chinamen, heavy, bushy-bearded Scandinavians, swarthy, powerful Malays, dark-skinned West Indians, and other exotic nationalities.

We now steam back to the dock, stopping on the way to examine two small sailing boats from Georgia. The lanky skipper of one of them—proud commander of a crew of six—when ordered to hand over his health bill and the obligatory fee of $1, in his anxiety and excitement risks a broken leg in his hurried scramble over the lumber piled up high on his deck. The necessary formalities are observed, however, and the worthy salt may proceed on his way.

The little steamer swings in at the dock once more, but it does not stay long. In a short while, a gentleman in civilian attire gets on board. It is Dr. Smith,* the Chief Health Officer, who is to visit Hoffman Island this morning.

* The above was written just before Dr. William T. Jenkins succeeded Dr. Smith. Another change must also be noted: the appointment of Dr. A. T. Tallmadge in place of Dr. A. W. Smith, deputies accompanying him.

All on board are veterans in the business. Dr. Smith has been in charge since 1880, succeeding Dr. S. Oakley Vanderpoel, and both the deputies, Drs. E. 0. Skinner and A. W. Smith, have also served for several years.

William Seguine, the Health Officer's secretary, with whom we are chatting in the stern, has held his office since 1876, and the spare-built man who is busy over a notebook, just outside of the pilot house, in which Captain E. F. Keegan has been turning the wheel for some eighteen years, is Richard Lee, who has represented the Associated Press here ever since January 1st, 1877.

We first take a run over to a couple of freight steamers from Havana. We are informed on the way that during June to September all ships from that port (which has the name of the most infectious one in the West Indies), or any other "yellow-fever port" from which the trip is made in less than five days, are detained until they have been away from it for that time, which is considered the maximum incubative period of yellow fever.

Various other precautionary measures further ensure safety against infection. The United States consuls in the West Indies, east coast of South America, west coast of Africa, the Spanish Main, Bahama and Bermuda, are expected to report immediately if infectious diseases become rampant at those places, or if the number of deaths from infectious diseases common at any of such places rises above the usual figure. (Thus, forty-five deaths a week from yellow fever is considered the maximum at Havana.)

In such cases, incoming ships from those parts are stopped at the Lower Quarantine, which is situated six miles below the upper station. Here a ship is always moored, from which such vessels are boarded. If there are cases on board, they are removed to Swinburne Island; the ship, after proper fumigation, being allowed to go on its way.

Formerly all vessels liable for quarantine were compelled to discharge "in quarantine," and were detained for periods of from ten to thirty days, the law providing for warehouses, docks, and wharves for such vessels.

Nowadays, exemption from long delays and substantial expense at Quarantine is the inducement offered to masters or owners of vessels to adopt vigorous protective measures against infection at the beginning of a trip.

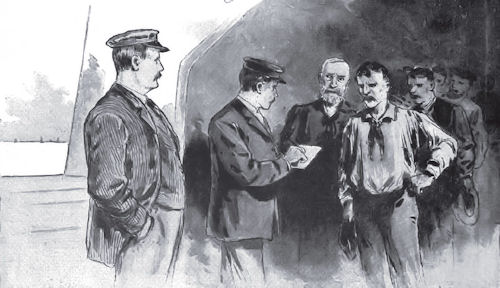

Fig 03 - Calling The Crew Of A Steamer

Vessels from ports subject to yellow fever, for instance, were formerly detained for forty-eight hours at the Lower Quarantine for fumigation, and then permitted to proceed to the upper bay, between Bobbin's Reef Lighthouse and Bedloe's Island, where their cargoes were discharged into lighters, and the vessel cleansed and allowed to proceed to the wharf.

Under Dr. William M. Smith's regime, much of this cumbersome and unnecessary mode of procedure has been done away with. If there is good evidence that the incoming vessel is not infected, it is allowed to proceed with as little delay as possible, the detention lasting only ten or twelve hours.

Masters and owners of such vessels, therefore, naturally strive to have a clean record, and do their best to preserve their people from contagion. As we have seen before, an exception to this rule is made in the case of vessels arriving from yellow-fever ports with passengers or a crew that have been on shore within five days previous to their arrival, which vessels are detained until the five-day period is over.

This plan has been attended by most satisfactory results, and the arrival of a vessel infected with yellow fever is an event of an extremely rare occurrence. In a word, ships are now restored to commerce with as much expedition as is consistent with the protective purposes of Quarantine.

Meanwhile, we have already reached the ships which are staying out the required five-day term, and after a double fumigation by oil of vitriol, in a number of buckets placed in the hold, will be allowed to pass up.

This done, we turn around and steam down toward Hoffman Island. On our way, we learn the object of our visit there. A steamer of the Belgian line came in, a few days before, with a smallpox patient on board. The sick man has been taken to the Reception Hospital in Sixteenth Street, New York City, and thence transferred to North Brother Island, in Long Island Sound.

Vaccinated Steerage Passengers

Those of the steerage passengers who had been successfully vaccinated before the breaking out of the disease were allowed to land, and the steamer passed on after proper fumigation. The Quarantine people immediately immunized the other emigrants, and they were then transferred, at the steamship company's expense, to Hoffman Island. Here they are visited daily, after the second day of their sojourn, by the Health Officer.

Those on whom, upon examination, the vaccination is proven to have been successful, are soon taken away; the others must remain for two weeks, within which period the disease will reveal itself if present. As they stay here at the expense of the steamship company, the latter has a good reason for seeing that its passengers are effectually vaccinated at the beginning of the trip.

The importance of doing this has frequently been urged upon them by Dr. Smith, and his efforts have been successful to a considerable degree. Dr. Smith also repeatedly pointed out the inefficiency of the medical service, especially on merchantmen, and suggested that better salaries be paid, so as to ensure the procuring of competent medical officers on ships.

Even the financial interests of the steamship companies would seem to demand this, for the incompetence or carelessness of the ship's surgeon often brings about detentions at Quarantine which are expensive to the owners of the vessel, and might have been avoided. In 1890 alone, 1,538 immigrants were removed from eight different steamers and kept at the Quarantine of Observation for periods varying from four to fourteen days.

While we are getting these facts we have already passed by Fort Richmond, and the mass of grass-covered earthworks beyond and above known as Fort Wadsworth, running along pretty near to shore in following the channel. It is getting cooler, and a stiff little breeze blows into our faces and drives the spray of the waves onto the deck of the tug.

A water boat lies at the dock of the island, vigorously pumping up Ridgewood (L. I.) water from its hold. The big yard beyond is swarming with immigrants, for some 500 have been relegated to this place for a two weeks' exile. A high fence encloses the mass of humanity on both sides, and the Quarantine people at once take up their position at a table by a gate, through which each person passes after being examined. It is now lunchtime, and we have a good opportunity of assuring ourselves that the immigrants kept here are well fed and cared for.

We clamber up on shore, and enter the New Administration Building, on our right. The examinations are almost completed, but the large dining room is still empty. We pass through the spacious kitchen, where large, fine chunks of meat are being cut up by the steamship's stewards, who are kept here with their steerage passengers, while the cook is perspiring and poking around about some huge kettles, in which potatoes and other eatables are steaming and simmering.

In all these rooms the ceilings are of galvanized corrugated iron, and the wails, up to a height of about five feet from the bottom, are made of imported white enameled bricks, the smooth glaze on which ensures cleanness, dryness and an absence of lodging place for disease germs, as does also the asphalt under your feet in the dormitories, which are located in two separate buildings.

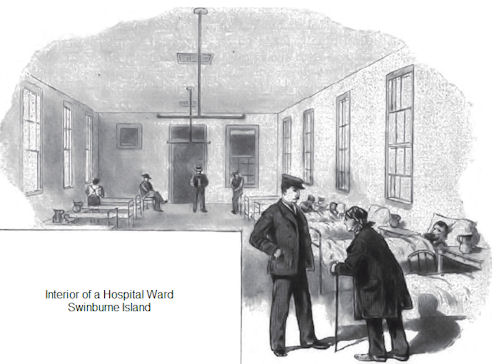

Fig 04 - Interior Of A Hospital Ward - Swinburne Island

The beds in these—bands of canvas stretched on frames of iron tubing—are folded upward and back against the wall and fastened to hooks when not in use. Mattresses were found to be of no particular use here except to breed vermin.

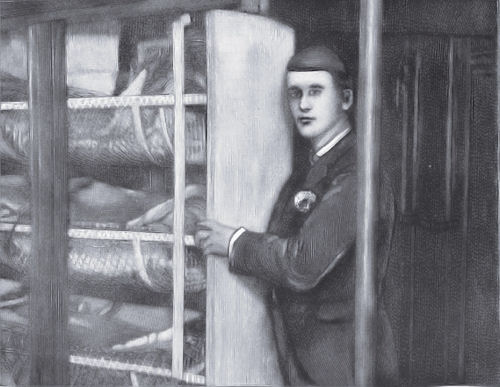

We then pass through the laundry, where the clothes are hung over horizontal poles fitted in upright boards at each end after being washed. These sliding frames are run together into a solid row, and steam does the drying, just as it does the cooking. From here we go up to what is, perhaps, the most interesting place in the building—the disinfecting chamber. This is occupied by a series of sliding frames, ranged along narrow passageways. In each of these frames, three wire baskets are hung, one above the other.

Each one of these baskets is intended to hold the clothing of one person or family when disinfection is going on. A tag is affixed to each basket, for identification, and the frames, which run on overhead tracks, are pushed back, their ends forming a solid along the passageway.

Everything in the chamber is of iron, and the place is as airtight as it can possibly be made. Nine thousand feet of coiled piping passes through the MOM.

The process of disinfection is to exhaust the air in the chamber, the stanchions in the room serving to support the enormous pressure from above. "The doors and room," we are told, "are calculated to withstand the pressure of 7 pounds per square inch," and gauges are so placed as to indicate the pressure. Superheated steam is let in under high pressure, rising to about 250°, more or less, as desired.

There is a thermometer in each of the three sections of the disinfecting room, and the degree of heat as shown by these is indicated to the engineer below utilizing bells over the door of the engine room, worked by electric connections. Thus the amount of heat desired can be regulated at will. After disinfection, the effects are taken, if necessary, to the drying room, where steam dries them.

Formerly, much of the work was done in the Old Administration Building, which contains Superintendent Bernard A. Owens's dwelling, as also accommodations for cabin passengers. But considerable and important improvements have been undertaken at Hoffman Island within the last three years, the necessity for them becoming manifest when the grim visage of cholera loomed up before the port in 1887 like a threatening thundercloud.

The importance of being ready for such dread visitors, who threaten destruction to health and business alike, was hardly recognized until so forcibly presented, but over $200,000 were then appropriated for the improvement of the Quarantine of Observation.

To mention but a part of the work that has been accomplished: The masses of sand around the buildings have disappeared under a layer of broken stones, and the whole place is paved with asphalt, the same material also covering the floors of the dormitories, and rendering them impervious to disease germs.

Fig 06 - Fumigating Room - Quarantine

Sixty-eight metallic bathtubs have been put up in place of the half-barrels formerly used. The closets discharge into porcelain-lined troughs, where the dejecta can be disinfected, if necessary, a valve closing the opening into the sewer until that object has been affected. They are placed in annex buildings erected beside the two dormitories, each building being divided into four sections, which communicate respectively with four corresponding divisions in the dormitory, divided off by galvanized iron partitions.

It is perhaps not very generally known that both Hoffman and Swinburne Islands are not entirely natural formations, but mainly artificial constructions. They are both built on West. Bank, a long strip of sandbar lying just east of the channel that runs southeast of Staten Island.

The sand is enclosed by cribwork protected by heavy riprap, and by a concrete wall surrounding each island, inside of the cribwork, and extending from below low-water mark to a foot above the surface of the islands.

The foundation of Swinburne Island was laid in 1866, that of Hoffman Island some two years later, the first being completed in 1870, the second in 1873. The improvements made within the last three years have, however, brought the cost of the whole up to pretty near $3,000,000.

Swinburne Island, as it now stands, after the improvements it has undergone—with its rows of hospital wards, its crematory and mortuary (masons des mores), the new dock, seventy-five feet, long, the breakwater that makes a safe slip north of this dock for vessels, and all the other necessary arrangements, as complete as any in the world—is as satisfactory as the plans intended it to be.

Hoffman Island, as we have seen, is not a hospital, but simply a "Quarantine of Observation," for those who have been exposed to smallpox or typhus, and 12,000 emigrants have been isolated here since 1880.

The other island, Swinburne, is a hospital pure and simple and is intended solely for yellow-fever and cholera eases. It has been used for this purpose ever since its completion in 1870, in place of the " floating hospital " called for by law. The ten white hospital wards, opening off from both sides of a central hallway, are airy and pleasant, each ward forming a building by itself. These, as also Superintendent John Butler's dwelling, is of wood, the other buildings being of brick.

Patients Who Die

Those of the patients who die are cremated unless their relatives or friends object. The effects of the sick are fumigated with sulfur, and in case of the owner's death, if not claimed by the heirs within two months, they are delivered over to the public administrator.

Those of the dead who are to be buried must be placed in metallic coffins, and if they die in the hot season their bodies go to the mortuary. Here they are placed in metallic boxes, and t h e latter sealed up until the weather becomes cooler. The mortuary lies just behind the crematory, in which latter place there stands a row of numbered brown earthenware jars containing the unclaimed ashes of some half a dozen of those who have been incinerated here.

Until a few years ago those who died in Quarantine were buried at Seguine Point, and when the crematory upon Swinburne Island was finished, in 1889, the remains of those buried at the cemetery were disinterred and incinerated on the spot, in a rude but effective furnace. Seguine Point was then abandoned by the Quarantine people.

Swinburne Island, by the way, was originally to be named after Governor Dix; however, by Act of May 15th, 1872, it received the name of Dr. Swinburne, under whose direction it was built.

Before the erection of these islands, and to meet the emergency created by the destruction of the Quarantine hospitals at Tompkinsville in September 1857, the sick were taken on board the hospital ship moored at the Lower Quarantine Station. Just below this ship is the anchorage ground of the Lower Quarantine, designated by yellow buoys.

Fig 07 - Superintendents House - Hoffman Island

The present ship, the S. D. Carlton, is really no longer the "floating hospital" provided for by law, but simply a floating station from which ships are boarded that come from ports infected by yellow fever or cholera.

The arrival of suspected vessels is reported by a very simple system of signaling, which works more surely and is less troublesome than the telegraphic connection formerly tried and found wanting.

The yellow flag that usually floats on the front of the "hospital ship "—from the foremast head— is transferred to the mizzenmast head, and its place is taken by the American flag. This is seen at Swinburne Island above, and from there the telegraph carries the news to the Quarantine Station, whence they go down to board the detained ships.

While absorbing all this information, we have once more boarded the tugboat. There is more routine work in the afternoon, but we put in a little time profitably chatting with Secretary Seguine, who gives us some interesting historical data, for Quarantine has its history.

The fact that the port of New York, through its extended trade, is peculiarly exposed to the introduction of contagious diseases, has at various times been brought rather forcibly to the notice of the powers that be, and numerous laws have been enacted with the view of providing for the protection of the public health.

As early as 1647 the Council adopted measures to prevent the introduction of epidemic diseases into New York. In 1714 His Majesty's Council issued an order directing that vessels from Jamaica should be quarantined at Staten Island, and two years later this order was extended to all vessels from the West Indies.

The first quarantine law for New York harbor passed by the Colonial Legislature was enacted in 1758, and provided for quarantine at Bedloe's Island; the State Legislature re-enacted this law in 1784. In 1794 the Governor was authorized to appropriate Governor's Island for quarantine purposes, and five years later Staten Island was designated instead, full authority being given for securing an anchorage ground and erecting a hospital, to be known as the Marine Hospital.

In 1801 the Quarantine establishment was finally instituted at Tompkinsville, Staten Island, upon the site of the present Cotton Docks, where it remained for over sixty years.

Though New York was no doubt satisfied with the change which removed Quarantine further from the city, Staten Island was not, and with the increase of population the growing hostility against the institution became so bitter that the Legislature, in 1857, passed an Act to secure the selection of another site.

George Hall, Egbert Benson and Obadiah Brown, the first Quarantine Commissioners to be appointed under this law, chose Sandy Hook, but New Jersey objected. Failing here, they pitched upon Segnine Point, at the southern end of Staten Island, and began with the erection of the necessary buildings. The inhabitants, however, cut off Quarantine from that quarter by turning out on the night of May 6th, 1857, and setting fire to the establishment.

A second attempt to obtain Sandy Hook having also failed, the old station at Tompkinsville was continued in use, which so incensed the surrounding population that they followed the example of their Seguine Point brethren, and on the night of September 1st-2d destroyed the place which their petitions and remonstrances had not been able to dislodge. The county, later on, had to foot the bills, for by law it was held responsible for the damage done by its mob.

To meet the emergency thus created, the Commissioners decided upon the construction of a floating hospital but changed their minds, and in 1858 hit upon " Old Orchard Shoals," in Raniton Bay, as a site, which plans also was not carried out. When, in 1859, another Commission was appointed, consisting of Horatio Seymour, John C. Green and Ex-Governor Patterson, the " floating hospital " idea was finally adopted, and the steamship Falcon purchased for that purpose and located below the Narrows.

The steamers Illinois and Empire City were subsequently also placed at the disposal of the Quarantine people by the general government. The Illinois served until 1888 when it was finally abandoned, and the B. D. Carlton purchased to take its place.

The arrangements were still inadequate in the early sixties. On the 23d of April 1863, however, the General Quarantine Act was passed, establishing a general system of quarantine for the port. By this Act, the permanent office of Quarantine Commissioners w a s created, and their duties and powers, with those of the Health Officer, were more closely defined.

Among the subsequent amendatory Acts was that of April 22d, 1867, which provided for a permanent structure on West Bank, as also a temporary one on Barren Island, and a landing and boarding station on the west end of Coney Island. Of the last two projects nothing more was heard, but the construction of Hoffman and Swinburne Islands, on West Bank, was duly undertaken, and then earns the location of the present hoarding station just above Fort Wadsworth, in 1874.

Fig 08 - On Board An Emigrant Steamer -Passing The Doctor

Thus, out of all these difficulties—occasioned to a great extent by the apathy of the people, out of which they were occasionally aroused by the alarming proximity of Yellow Jack and cholera—there has arisen a Quarantine establishment that probably excels in completeness any other in the world.

The confidence felt in its efficiency has made the air of secrecy which formerly enshrouded all doings at Quarantine a thing of the past. Still, if the methods down there were as well known as they ought to be, some of the misstatements made by the newspapers during the late " hunger-typhus " scare might have been avoided.

Fig 09 - Vaccinating Immigrants

A perusal of the collected laws relating to Quarantine will convince us that they are in some measure antiquated and conflicting, but the jurisdiction of the Quarantine establishment extends from Sandy Hook to Hell Gate, and the Health Officer is invested with almost unlimited discretionary power, which has been used with good judgment.

Anyone aggrieved by a decision of the Health Officer, however, may appeal to the Commissioners of Quarantine, whose decision, in that case, is final.

Violation of the Quarantine regulations, or obstruction of the officers in the performance of their duty, is punishable by a fine of not less than $100 nor more than $500, or by an imprisonment of not less than three nor more than six months, or by both such fine and imprisonment. And masters of vessels who refuse or neglect to furnish all necessary information to the Health Officer are punishable by a fine not exceeding $2,000, or by imprisonment not exceeding twelve months, or by both.

By the law of April 11th, 1888, the annual salary of the Health Officer was fixed at $10,000, and all fees were legalized. The fee for the inspection of vessels from foreign ports was reduced from $0.50 to $5.00, and that for vessels from domestic ports south of Cape Henlopen, formerly $1.00, $2.00 and $3.00, according to the tonnage of the vessel, has been fixed at the uniform rate of $1.00 for all classes.

The fee for boarding at night is reduced from $15.00, $10.00 and $8.00 to the uniform rate of $5.00, and the same amount constitutes the disinfection fee, which formerly ranged from $3.00 to $8.00.

Since the Act of 1801 was passed, providing for the appointment of a Health Officer, the following M.D.'s have served in that capacity :

Physicians Serving As Health Officers Since 1801

| Name | Date of Appointment |

|---|---|

| John R. B. Rodgers | October 5, 1803 |

| Benjamin De Witt | March 6, 1815 |

| Joseph Bayley | February 4, 1820 |

| John T. Harrison | April 24, 1823 |

| John S. Westervelt | February 25, 1829 |

| William Rockwell | February 10, 1836 |

| A. Sidney Doane | February 14, 1840 |

| Henry Van Hovenburgh | February 8, 1843 |

| Alexander E. Whiting | January 28, 1848 |

| A. Sidney Doane | April 4, 1850 |

| Richard L. Morris | April 10, 1852 |

| Henry E. Bartlett | April 21, 1854 |

| Richard H. Thompson | April 21, 1855 |

| Alexander N. Gunn | April 6, 1859 |

| John Swinburne | March 19, 1864 |

| John M. Carnochan | January 2'7, 1870 |

| Samuel Oakley Vanderpoel | February 28, 1872 |

| William M. Smiths* | March 27, 1880 |

* Dr. William T. Jenkins succeeded Dr. Smith on February lst, 1892.

While we are listening and reading, a steamer of the Compagnie Transatlantique has come in. It is growing late, and a raw wind has arisen and blows hard over the water, while the sky has become dismally gray in tone. A merry babble of voices is borne over to us from the deck of the steamer, and the shrill, squeaking notes of a clarinet rise high above the faintly heard hubbub.

They are anxious to reach the Compagnie's dock before nightfall, and the big ship steams slowly up the bay, with the small black-and-white Quarantine tug puffing along beside it. They have lost some time already, because the Portuguese steamer that came in just before from the Azores has been subjected to a very thorough and careful examination, it having brought smallpox on its two preceding trips. But there is no more work to be done after this, as it is nearly six o'clock, at which hour the working day ends here.

It is with a feeling of relief that we get out of the damp wind at the waterside, and board the northbound train at the Fort Wadsworth station, a quarter of a mile beyond.

But as we glide homeward on the Staten Island Ferry boat, our glance, following the impulse of the many impressions we have received, naturally turns back once more in the direction where New York has set up her wall of protection against the insidious attacks of subtle and deadly epidemics.

White, Frank Linstow, "Barriers Against Invisible Foes" in Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, Vol XXXIII, No. 6, June 1892