The Anomalous Quarantine Situation In New York Bay

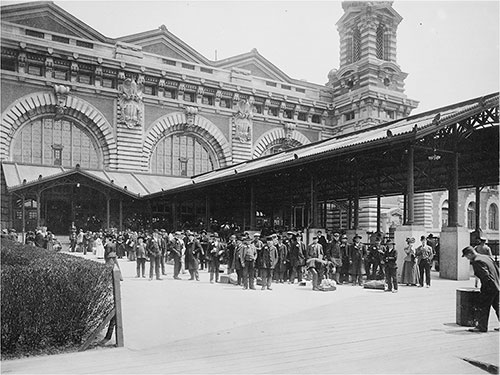

Immigrants Standing Outside the Main Building at Ellis Island circa 1910. National Archives and Records Administration # 6235189. GGA Image ID # 19f5894b4b

By SHELBY M. HARRISON

New York is the important quarantine port in the United States and probably worldwide. For the last half-dozen years, the total number of alien immigrants to the United States has averaged nearly a million, and almost seven-eighths of them entered through the port of New York.

Over 60 percent of these came from southern and southeastern Europe, where sanitary conditions are primitive, and cholera outbreaks are uncommon.

Between May 8 and November 1, 1910, 204,959 cases occurred in Russia, resulting in 95,673 deaths; from August 17 to November 1 of the same year, 1,814 cases and 899 deaths occurred in Italy.

In the last week of September 1910, there were 377 cases with 130 deaths from cholera in Naples alone—one of the embarking points for America.

Moreover, New York is one of the most important ports of entry from the West Indies and South and Central America, where the yellow fever problem has not yet been entirely solved.

Of course, vessels bringing immigrants also carry valuable cargoes of imports; and modern quarantine involves thorough and efficient inspection of passengers to detect quarantinable diseases while at the same time obstructing and delaying commerce the minimum amount.

During the last five years, the value of imports landed in New York City averaged almost $800,000,000 per year, an amount more significant than the imports of all the other United States ports put together.

Over one-eighth of this was from southern Europe, $50,000.000 coming from Italy. And yet, although the federal government conducts forty-four quarantine stations of its own, the station at New York, as is the case at only three or four other places, is maintained as a state station.

Because of the recent call by the governor of New York for the resignation of the health officer of the port, the time would seem reasonable for raising the question of transferring the New York quarantine station from state supervision and control to that of the federal government anew.

After being boarded far down the bay by their harbor pilot, incoming vessels bound for the harbor of New York must pass three kinds of barrier stations before they may land their passengers in the United States.

Standing on either side of the Narrows is the first—the military outposts at Fort Wadsworth and Fort Hamilton—set up to keep out invasion by a foreign military force.

Invasion of our shores by a hostile army has long been considered of vital concern to all the people of the United States, and means toward prevention are furnished on a national basis.

The soldiers who man the forts are representatives of the national government, and the physical equipment with which they work is owned and under the control of the federal powers.

While New York City would be the first and heaviest sufferer in case of a forceful attack upon the United States through this port and is therefore especially interested in solid fortifications down the bay, nevertheless the general government has assumed the responsibility for defense and spared no pains nor expense in obstructing against the undesirable entrance.

Furthermore, the hazards involved in possible military invasion have been thought so great that army service has been removed from either political control or local influences, which might in any way weaken its efficiency.

Up the bay, a little farther, is the second barrier, the state quarantine station. This barrier is also set up to keep out destructive invasion. No foreign army or fleet could play such costly havoc with the - general welfare or shatter our domestic peace as could the charge of pestilence.

Such an insinuating devastator of life and homes concerns more than the state of New York, for most of the possible carriers of contagion who enter the port soon scatter through many states. For instance, out of 850.000 aliens inspected in New York in 1910, all but 280,000 intended to reside in other states than New York.

Therefore, their physical condition is of interest to Kentucky, Ohio, Illinois, or Nebraska, and indeed to New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as well as to New York. Yet New York shoulders the burden of protecting the nation.

Roughly, over three-fifths of the immigrants entering through New York stay in five eastern states; yet, again, the other four states do not share with New York in quarantine inspection. Two islands just below the Narrows, Hoffman, and Swinburne, are fitted up for detention, observation, and treatment of incoming passengers.

The administrative headquarters are on Staten Island, just at the Narrows. Swinburne has four small hospital buildings housing isolation wards; it has comfortable quarters for officers and nurses, a crematory, and a morgue.

The island is used exclusively for the isolation and treatment of persons suffering from any of the generally recognized quarantinable diseases, namely, cholera, yellow fever, plague, leprosy, smallpox, and typhus fever and for observation of all except cholera suspects.

Until about two years ago, Hoffman, the other island, was used as a detention place for persons exposed to these diseases. At that time, however, the health officer prepared to detain persons afflicted with such contagious diseases as scarlet fever, measles, and Diptheria and accordingly fitted up a building to be used as a hospital for treating these cases.

Early last summer, when an invasion of cholera from Italy and southern Russia was threatening, another change was made, and since then, the Hoffman Island equipment has been reserved as detention quarters for cholera suspects only; and immigrants suffering front scarlet fever, measles, etc., have been sent to the federal hospital on Ellis Island.

The federal authorities had anticipated the increasing demand for hospital facilities and were adequately provided when this class of cases came to them.

The legislature of New York has repeatedly expressed the sentiment that the quarantine station should support itself; in other words, one should assess the cost of quarantine inspection and other services against the steamship companies.

Almost up to the beginning of the present administration at quarantine, the state felt no financial burden. The health officer was allowed to keep all fees collected above the expense of conducting quarantine.

That plan kept expenditures for improved service and better equipment to a minimum, and the office was regarded as a "gold mine" for the incumbent.

Fees assessed were: $5 for every inspection, regardless of the size or sanitary condition of the vessel; $2 additional for each two steerage passengers or fraction thereof; and from $5 to $50 (in the discretion of the health officer) for disinfecting a vessel.

Although these fees continue to be charged in recent years, the health officer has been paid a salary, and the state has made up deficits in the station's finances.

Owing to the increased carrying capacity of steamers, thereby reducing total fees, on the one hand, and to the increase in sanitary knowledge, the rising cost of administration, on the other hand, these annual differences between receipts and disbursements have grown until the legislature now furnishes about $75,000 per year for current expenses.

Thus, commerce into New York and the state of New York are together taxed so that the nation may protect itself against disease.

Further up the bay at the immigrant station on Ellis Island is the third breastworks thrown up against foreign invasions, and there, as at the forts, the federal government is again in charge.

The immigration station bars entrance of manifestly objectionable classes of immigrants such as idiots, imbeciles, the insane, paupers, persons likely to become public charges, persons with loathsome or dangerous contagious diseases, persons whose physical or mental defects might prevent them from earning a living, criminals, procurers, and prostitutes.

The government has expended several million on buildings and equipment. Although there may still be a need for more equipment, the comparative expenditures of the state at the quarantine islands and the federal government at Ellis island argue the more extraordinary ability to furnish and greater ease in obtaining large appropriations from the national resources.

In addition to the million-dollar administration building with inspection and detention quarters and other smaller facilities, the government has two huge hospitals, one of which includes thirteen large isolation wards.

More than 500 officials, exclusive of those in the hospital service, are regularly on duty at the station. Physical examinations are made by officers in the United States Public Health and Marine Hospital Service, who have charge also of treatment in the hospitals.

During 1910 the total number of immigrants admitted to this and other hospitals cooperating with the immigration station hospitals was 8,649; the total of clays' treatment furnished amounted to 58,559, and the daily average number of patients in the hospital was 160.

In that year, the chief medical officer reports that 19,545 aliens were certified for physical or mental defects, including 1,735 classified as loathsome, contagious, or dangerous contagious, trachoma 1,442, tinea-tonsuraus 94, favus 84, tuberculosis 32, syphilis 13, gonorrhea 32, etc.

Nine thousand, three hundred, and fifty-one were certified for disease or defect which affects the ability to earn a living, including senility 2,637, hernia 1,478, valvular disease of the heart 384, a curvature of the spine 310, etc.

Many officers required in this station of the marine hospital service and the 500 and more other employees, who are protected by the civil service, feel only the minimum of political interference.

Here, then, are three national frontiers, and yet at one of the three New York state shoulders not only the moral and physical but the financial responsibility of protecting against foreign invading foes.

At all of the smaller ports of entry sprinkled about our shores, and at nearly all of the larger ones, the states have given protection from disease invasion to the federal government.

New York, with the largest and most costly port to supervise with immigrants fast scattering to all states, with a federal station in its largest harbor protecting against the morally, physically, and economically unfit, stands most conspicuously in the way of a uniform system of inspection and detention throughout the country and a standardizing of the administration of quarantine stations.

THE SURVEY SOCIAL CHARITABLE CIVIC, VOLUME XXVII, No. 17 WEEK OF JAN. 27.1912

SWINBURNE ISLAND, NEW YORK' QUARANTINE, LOWER BAY.

Isolation quarters where persons afflicted with cholera, yellow fever, plague, leprosy, small-pox, or typhus fever are treated. Maintained by the state of New York.

HOFFMAN iSLAND, NEW YORK QUARANTiNE, LOWER BAY.

Until last summer used as detention and observation quarters for persons exposed to cholera, yellow fever, plague, leprosy smalll-pox, typhus, scarlet fever, measles, and diphtheria. Now reserved for cholera suspects only. Maintained by the state of New York.

ELLIS ISLAND IMMIGRATION STATION. UPPER NEW YORK BAY.

A barrier set up against entrance Into the United States of manifestly objectionable classes of immigrants such as idiots, Imbeciles. the insane, persons with loathsome or dangerous contagious diseases, etc. Maintained by the United States.