In The Paths of Immigration to America - 1902

It is ten years now since that well-remembered epidemic of cholera in Hamburg among the Russian immigrants, which, being carried by them into New York Harbor, for some weeks kept this country in a fever of dread.

Cholera did not obtain a hold among us at the time, nor afterward, but we can all very well recollect how general was the fear of it; ever since then the business of transporting this class of travel has been allowed to continue only under the strictest oversight by the health authorities in this country and abroad.

As an outcome of the restrictions imposed in 1892, the poor Russian who would now leave the old country for this more careful, if also more promising land of ours, finds his road hedged in with all kinds of bewildering regulations.

He comes—to take a well-traveled route —as one of several car-loads to Eydtkuhnen, the largest of the frontier towns of Germany, where a combination of four great Continental steamship companies has established, under the supervision of the German authorities, what are called "control-stations" —places where the immigrants are examined and inspected, persons and baggage, and detained in isolation until such time as there may be enough of them to make an economical shipment to the port where they are to take steamer.

The idea is to keep them together, to allow them to mingle with none outside their own class—class as the authorities have determined it—until they are safe aboard ship.

A timid, wondering lot they appear to be when the train finally arrives at Eydtkuhnen. Before coming to the little bridge that spans the creek dividing the two countries here, they have been able to make out the armed Russian sentinels pacing back and forth, less than fifty meters apart, and very watchful that no man, woman, or child crosses the frontier without the usual papers. If the stranger must have a passport to break into Russia, the native needs a similar document to get out.

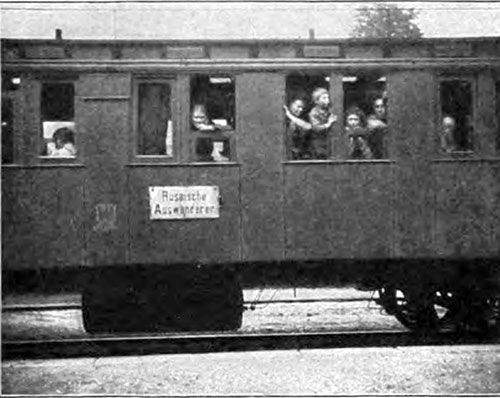

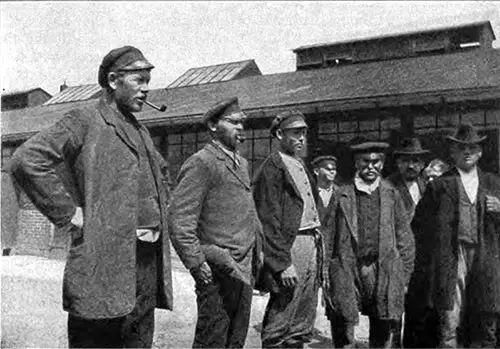

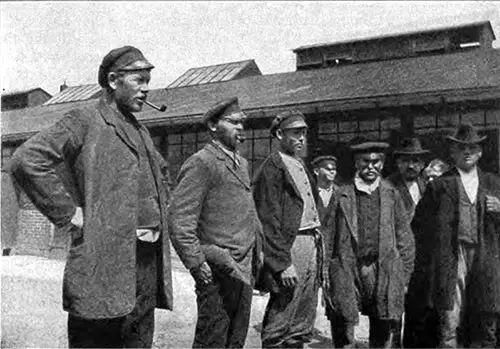

Russian Immigrants en Route to Hamburg. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fbe8886d

The train comes to a full stop. Their car-door is unlocked, a guttural guard " harasses " them out, and they scramble out and down to the platform with boxes, bundles, and babies dragged below and carried aloft.

As Eydtkuhnen is a town of some importance, there are those from the train who, having some business to transact, are away to attend to it, after, of course, an inspection of their tickets by the uniformed guardian of the gate.

But our immigrants, though they do not know what is to happen next, know very well that their way lies not after such free people. So holding on to household goods and children, they halt for further orders.

A Continental immigrant early learns that when he arrives in a strange place, he must do nothing whatever in the line of progress until some official person in uniform comes along and gives him orders.

However, they are looked after eventually. " Auswanderer, Auswanderer, Herr Greunmann," shouts somebody, and another uniform comes along — epaulets, green coat, red stripes, buttons, and the cap with the official rating in metallic letters—waves an inclusive arm, and in the patois of some province or other of their country, which some understand and some do not, shouts at them that soon they will be taken to the steamship company's lodging-house and there attended to.

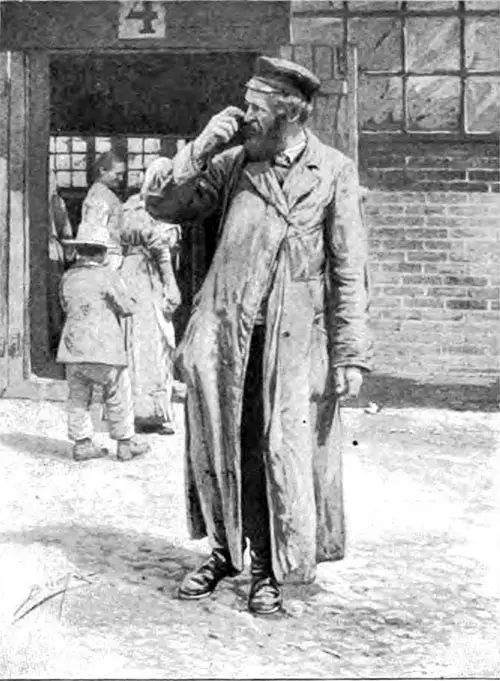

And then comes the first man thus far out of uniform with whom they have had to deal, the superintendent himself—Herr Greunmann—a large man, with good-humor in his face, who goes among them, asks a question here, examines there, and finally gives them in charge of a little old man, with a puckered face, who skillfully masses them in an irregular square and starts them off for the company's lodging-house, where they are to stop for the night.

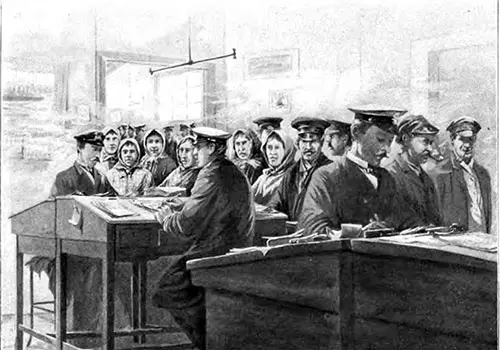

Examining Immigrants' Papers at Hamburg. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fc646673

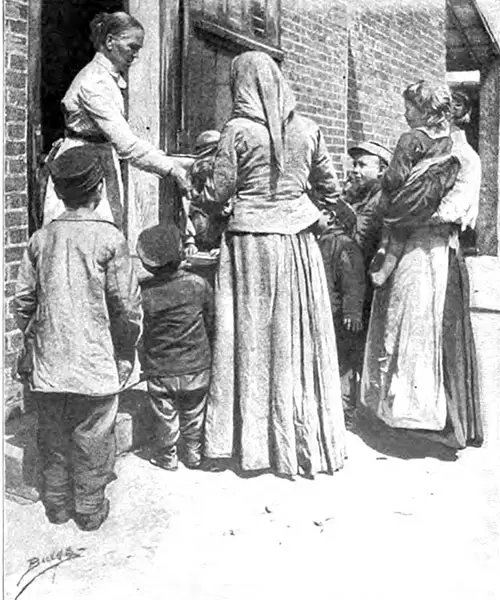

A two-story house is this where they lodge, wherein the floors are well-scrubbed, with separate rooms for men and women, and bunks clean and inviting, though stacked in tiers and divided one from the other only by iron piping.

On the ground floor is the kitchen, with long tables, on which always may be found the useful samovar. In the yard is a pump for fresh water, where the women may wash the dishes or small pieces of clothing, and against the walls are benches, whereon the men may sit and smoke and talk of things to come.

Immigrants at the Kitchen Door. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fee2eb12

There was, to bother them, a man of the company, not a learned man nor a man of importance, just one who looked like themselves, who went about without a uniform—yes, without a coat even—and who made it his business to be forever telling them that they must keep the place clean.

To his bothersome ways, they became accustomed only after two-three routings, when they minded him no more; and the building and its arrangements were excellent. Indeed, they all took great comfort there.

The next day, in the middle of the forenoon, came again to them the shrewd-looking little old man, who had led the march from the railroad station. Now he counted them over, up and down, and marched them, with their bags and bundles and babies, through the streets of Eydtkuhnen to the control-station. They had heard of that place, the control-station, and they knew that their ordeal was coming.

Manager of the Control Station at Eydtkuhnen. Chernyshevskoye (Russian: Черныше́вское; German: Eydtkuhnen, from 1938: Eydtkau); is a settlement in Nesterovsky District in the eastern part of Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia, close to the border with Lithuania. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fc070a9d

They measured it up when they came to it—many buildings with a high fence all about, a gate that locked behind them, and a long boardwalk down which they filed under the hot sun until they came to the last building of all.

Here they huddled together under the searching eye of a man, whom they all knew at once for the surgeon that was to examine them—lie that was to say who had disease of the hair or the eyes, or any of the other forbidden infirmities—to say who might go on to America and who must go back to Russia.

A look of business had the surgeon. Fifteen thousand came under his hands and eyes every year, though our immigrants did not know that. The forty here now hardly made an average day for him, and he went at them with precision. First, he sized them up.

Then the commands: " Now then! caps off and shirts open! " He didn't even look carefully about to pick any particular one, but suddenly said, " You ! " and the man at the head of the line jumped painfully.

It was a lesson to watch that first man who had to face the surgeon. We, who have never lived in a country from which we are longing to escape, might not feel as did this man, to whom pretty nearly everything of the moment in the world was at stake just then.

There might be something wrong with his eyes or hair, or with some part of him inside—he did not know.

He had never before been examined in this way by a doctor, and how was he to know? And so many had come back, too. Think what it meant to him if he was sent back.

The money for his passage had come from a relative in America. In essence, possibly all the relatives for whom he cared were already in America. Think about what this meant to him.

And so he faced the surgeon, while thirty-nine others fixed distressful eyes upon him as the indicator is a measure of their own fortunes. As he was served, so too would they be served. As a brave conscript might face his first battle, so did this man arise and walk toward the surgeon.

It is a deep breath, and a tautening of the ligaments, He draws nearer. The eyes begin to set, and the lips to tighten. He stands rigid before the man who is to decide his fate.

The surgeon's hand draws his head forward, and the man quivers. With the fingers rolling back the lids of his eyes, The surgeon's voice commands his eyebrows to the light, and the man shivers.

The surgeon drops him, and his chest flattens, and his shoulders droop. Still, quickly the chest rounds out, and the shoulders are squared when the professional hand again reaches for him, now to tap him over the heart and sound the lungs.

Another look at the hair and he is motioned on. He is not yet through, but he has passed thus far, and the shadow of tears leaves him. And around the room runs a wistful sigh of confidence. As it has been with him, so it may be with them.

However, there were several rejections. There was the old woman who had come with her daughter and her daughter's children. The daughter's husband had sent the money on from America, and they had been rarely happy that morning.

Three more days and they would be on the great steamship, and then!—it was but a short trip to America then I But the old woman had a disease of the eyes.

Did she not know? Know ? and how should she know? A sickness of the eyes! She touched them with her fingers. Her eyes? She had seen to sew with them all her life.

Why, she had seen to make all the clothes for all the babies with them—for all the babies. Only the last night at home, she had finished the dress the littlest one was even now wearing—oh—oh—the little baby!

She looked over at the baby, and in her poor old eyes, despite the love of two generations, was seen the reason for the surgeon's decision. And the rejection held.

There was a young man, and a girl trying to soothe him—not an uncommon case—talking bravely to him as they sat together, she on the top of a green box and he below her on a round bundle of bedding.

They may have been brother and sister, they may have been betrothed -- indeed, they cared for each other, and now they were to part.

There was another, a man of middle age, who sat over in the corner, as far away as he could get, with his bundles and boxes about him. When the door of that room should be thrown open and the gate of the control-station unlocked, he would be allowed to go out and wait for a train to take him back to Russia.

He was a strong one, who had earned his passage-money himself, but now the years of saving were gone for naught. He would go back and live out his life in hard Russia, not in beautiful America. Why had somebody not told him and spared him the extra toil? What for now were the nights and days of pleasure he had put aside?

He looked about him. Dry as the old woman's eyes were his own hopeless eyes, but for him, there was not even the prattle of a little child to lead to an hour's forgetfulness.

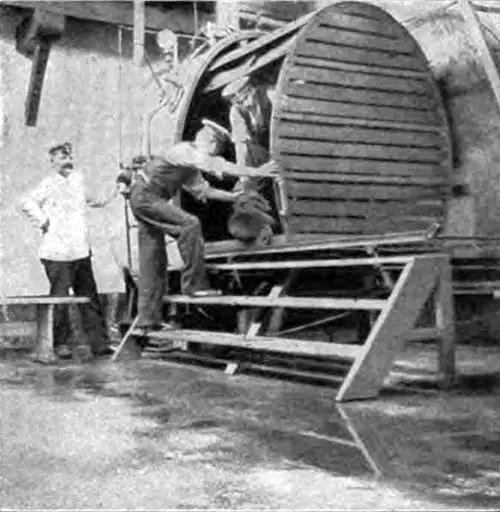

The accepted ones passed out of that room and into another, where, on command, they discarded coats, waistcoats, and hats, which were piled up on the slatted tables—coats, waistcoats, and hats in separate heaps.

For any money or jewelry, they might have to check they received a numbered tin tag, which was hung around the neck by a string, and guarded as if it were a religious token. Some seemed to have nothing to check.

And now they were told to separate, the women to the right-hand room, the men to the left, where they were to take a bath while their outer clothing should be undergoing disinfection in the big steam-box.

On the men's side, the surgeon came again and examined them yet more closely. There was no delay, except for consultation over a young man who happened to be gifted with a right dorsal muscle that stuck out like a fin. He was a young fellow with a good face, which blushed during all the time his muscular formation was under discussion.

His name was shouted back and forth. The superintendent was called in to look, and then somebody else was called in to look. Every other immigrant in the bath-room stretched his neck and had a look. The lad squirmed. There was nothing there to hinder him from becoming a good citizen or doing a good day's work—they agreed on that.

And he seemed to be a well-behaved and hard-working lad, too. But this peculiar development had to be noted, despite the lad's mortification. So they set it down on a blank form, with his name, and age, and other things, before they allowed him to pass on to his bath.

After the bath, they had only to go down to the superintendent's office, settle for their tickets, if they had not already done so, and then all sit around in the waiting room until the officials should make ready the train that was to take them on to Hamburg or Bremen or whatever port it was to be.

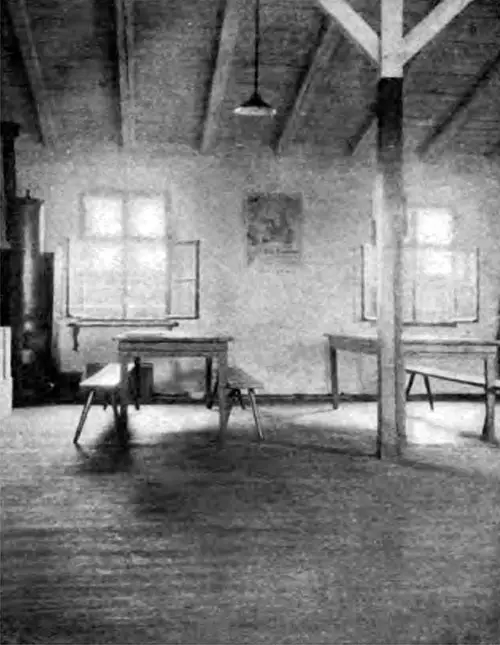

Immigrant Waiting Room -- The Immigrants Sit in This Room Till the Train Is Ready to Take Them to the Coast. Each Table Has a Samovar for Their Use. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fbd9106f

So they waited, with everybody having a little something to eat while waiting. And a little something to drink, too. There were two tables with a good-working samovar on each, and they made tea and got out their bread, cheese, and dried beef.

Some there were who had sweet brandy, by these much preferred to tea. So they ate and drank and chattered and looked after the babies —and there was a nursery of babies—watching them while they rolled around, soothing them when they cried. Things were looking brighter now.

They had hoped to be away by the middle of the afternoon, but it was nearly dark when the train pulled out. A half dozen had come to join them during the day, and they were now forty-odd in number, divided between two little cars at the end of the train.

Such little cars! No seats such as are given to ordinary travelers, but narrow benches, lengthwise along the sides. By crowding close, they all found room.

It seemed to be a sort of accommodation train this, that bumped along after a way of its own and stopped at the smallest stations. All along the road, people left the cars and went away—that is, from every car except theirs.

They were locked in, although not on that account forgotten. Whenever they seemed to be side-tracked, or whenever, for one reason or another, the train halted for longer than five minutes, a man would come, always in uniform, stick his head through the upper part of the door.

He would gaze around upon them, count them over, and check up the tally on what must have been his official list. "As if we would escape!" commented an immigrant with an eloquent shrug of the shoulders.

There was not much sleeping among them that night. They curled up on the benches and on the floor and pretended to sleep, but there was really very little sleeping among them.

They had had a good sleep in the lodging-house at Eydtkuhnen the night before, and because of that, and possibly because this was really their first night away from their own country, they did not feel quite like it.

The babies slept, of course, though restlessly, with now and again a cry for the mother. It was instead a springless sort of car for young ones, but they slept. At every station, the more nervous of the elders were up and crowding the little square windows to see what was doing outside.

At such places, there was a great banging of doors from the other cars, but nothing from their vehicles. Their doors were shut and kept shut. But the guard, the inevitable man in uniform, kept looking in the same as ever, except that now, with the darkness covering all things, he held up a lantern.

It was good when morning came, and especially good when they were allowed to leave the car at one station and get under a pump. It had been a hot summer's night, with no water in their cars, and they bathed hands and faces, and let it run streaming over neck and chest, and drank it up until they could hold not another drop. Ah, but it was good! And they filled their water-bottles until they spouted from the neck like little hydrants.

Back to the cars after that, and then their morning meal, which was much the same as at Eydtkuhnen, except that now there was no samovar, and so no hot tea, no fine coffee. Some, grieving for their usual tea or coffee, consoled themselves with a swallow of sweet brandy from companions more variously provided.

Later in the morning, the station boys, who attended the trains with loaded trays of foaming beer, sometimes found time to come to them, after all the other cars had been supplied, and then it was good that beer; but not all could afford it.

Through all the long, hot days, the train made its way over the fertile fields of northern Germany. At every station, our immigrants could see men and women rush from the train toward the platform, and other men and women rush from the platform toward the train, and meeting, there would be a laugh, a cry, an embrace, and children, maybe, held up to be kissed.

But none rushed from out of their cars, no more than did any rush toward their cars for greeting. And babies to be kissed! Yes, when they cried, a mother's kiss was needed to quiet them. However, these others did not mean that they were to remain unnoticed.

Quite often, people did come up, and stand, and stare at them, and read and re-read the placards beneath the little windows of their two cars.

RUSSISCHE AUSWAN DER ER it said on each placard—RUSSISCHE AUSWANDERER—in big black letters.

People spelled that out—not the best of people, perhaps, but yet free people, who could come and go as they wished—people spelled it out and repeated it to each other, and then looked up at them with immense curiosity—and sometimes laughed aloud.

In the evening they came to the great city of Berlin. None of them had ever seen Berlin before, and none of them could say for sure that this was Berlin, but in some way, the word got to them, and they gazed eagerly out of the little windows.

Berlin! They knew of it like the great city of the vast German Empire, as St. Petersburg was of mighty Russia. Berlin, St. Petersburg, London. Paris—they knew them for the great cities of the world.

And this New York they were going to? Larger than them all said one. Larger than Berlin? Yes, indeed. All they gurgled at that and took a fresh look at the lights of Berlin from out of the little windows.

They were held for several hours at Berlin, guarded more carefully than ever, and before they left it, some time in the middle of the night, other cars were added to the train—from Poland, Austria, and southern Russia they were told—and all went on together.

The morning was longer in coming this time, even though earlier in the evening, they had thought they would be sleepier than on the previous night.

All day long, they had been munching at their mediocre food, but munching is hardly eating, and there had been no hot tea, nor coffee, and they missed them so. They were thirsty, too—no water in their cars since Berlin, water-bottles empty, and no chance to refill them along the way.

They had stopped at many places—it seemed as if they were forever switching and jolting —and at many of these places, they had seen drinking-fountains. Still, the guards would not open the doors for them, and nobody quite dared to climb through the little windows.

They slept all over the car that night, curled up on the benches, tucked tinder the benches, sprawling about the floor, and two there were with heads under the stove that still remained in the car from colder days.

The benches were not so bad, though some Aas wide as a small man's foot was long they were, and some managed to hang on to a three-foot section of it lengthwise. By bending the stiffening joints, one could manage.

The great trouble about sleeping was that the benches not being fastened down, and also the legs not being quite equal in length, and the floor not quite even, and the matter of flat wheels and bad springs not having been carefully looked after in the construction of their cars—the bother at times, also accented at sharp curves, was to stay in the same spot where one turned in, especially if it was on top of a bench and not under it.

And so it happened that most of them awoke many times during the night to the fact that their sleep was not as sweet as they had found it in dreams of happier nights. But even to these mornings came at last. With apathetic eyes, they arose and viewed the sliding landscape.

By this time, they were rather tired of that same landscape, and it drew no particularly approving comment from them. Still, when the emigrants heard that they were nearing Hamburg, and when at length they came into sight of that city, they stirred themselves.

The tall masts, the first signs of the immense shipping of the port, were viewed by them with wonder. Some of them had never before seen a ship. They had seen riverboats in their own country and along their line of travel, but nothing like these tall ships in the distance.

When the train stopped—and for them the last time it was to stop — they found themselves close to the famous Auswanderer-Hallen, the most exquisite thing of its kind in the world, descriptions of which had come back to them from friends and relatives have gone before.

Immigrants On the Way from the Train to the Auswanderer-Hallen. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fe4c8e95

A collection of many fine buildings they saw it to be, with a fence around all, the same as at Eydtkuhnen, though here it was a much more luxurious place.

For those who could not carry all their bundles in one load—and there were some such among the old women especially tired after their long journey —for these, there were stout young porters of the steamship company to take what was left behind. This was good of the company indeed, although they had no manner of doubt that it was done to save valuable time.

Emigrants at Auswanderer-Hallen. nd, circa 1890. GGA Image ID # 14feeca2eb

In the waiting room were the most comfortable benches—benches with backs—and on the walls, the notices were in Russian as well as German, and indeed that was a great convenience.

A keen-eyed energetic little man, surprisingly agile for his age, hopped in and about among them, asking questions of everybody and taking care to put them all in the right way of things.

Like a clicking mill-wheel he was, so snappy and quick, but he was kind to the women and children and patient with the men. It was he who saw them to a room where, behind a rail and many desks, were many clerks asking quick questions and setting everything down on large sheets of paper. Such foolish questions, too, some of them, and such personal matters, others, but, of course, one had to answer.

And more examinations in baths, not for them who had come from Eydtkuhnenno, God be praised, not for them—but for some who had come from other places, and for others of whom the surgeons were not quite sure. Eyes and hair again, yes—and bundles that did not have the red disinfecting cross to go through the steam-box yet.

The Big Steam-Box in Which the Outer Clothing of the Immigrant Undergoes Disinfection. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fea1d561

It was the control-station all over again. But here things were so much better. Honestly, one could go through this examination, if examination there must be, in comfort.

Comfort? Luxury! Such great high rooms, with cement floors all so clean, and in the bath-rooms white tiles against the walls and porcelain basins to wash the face and hands in—everywhere arrangements like that.

The Last Examination of Immigrants Before Heading to America. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fc90aed7

Was it not like in beautiful houses? And if one had money, there was a Hotel Nord and the Hotel Sud. Such large buildings they were, one for the women and the other for the men, where for two marks—one ruble—in the day, one might sleep in a bed in a room where only three other beds were and could eat in a tremendous extensive hall, where hot faces might be cooled by the pleasant breezes that came in from the veranda through one door and out the other.

And there were the shops where things could be bought cheaply, one for the men and another for the women, outside each of which it was painted beautifully on a tall board what one could buy inside.

Skirts, shoes, stockings, corsets, gloves, bonnets, parasols, and what not—everything a woman might need if she wished to look her best when at last, with the long voyage ended, she stood among her friends on the other side of the vast ocean.

For the men, it was the same—the tall board with the paintings of shirts, suspenders, waistcoats, hats—such elegant, round, hard hats. Who could not be satisfied?

And when it was time to eat, there were separate kitchens for Jews and for Christians, and eating places also apart. And no weak one need be tempted through shame or hunger to avoid religious duties here.

There Were Separate Kitchens for Jews and Christians. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fd2a1087

When it came time, there were the places of worship for all; for the Jew his synagogue with the round top, for the Catholic his church with the cross, and for the Protestant also a church, with a place for the Emperor—all elegant buildings with plenty of seats.

And in the evening there was the garden, along the paths of which were placed such comfortable benches, where once more the elderly men might sit together and smoke and discuss the more important things. The younger ones sit and talk or remain silent, as they wished.

That night they went to bed by electric light, in a long room, where the cots were not in tiers as at Eydtkuhnen, like one full bed divided into spaces by iron piping only.

The Cots Were Like One Wide Bed Divided Into Spaces by Iron Piping. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fbc36658

Still, here there were two rows of beds, every bed resting on the floor by itself, with a decent space on either side, so that he who cared might feel free to undress, and not go to sleep in his clothes.

And if it were cold weather now, those of them who knew told the other wondering ones that they would be kept warm by the steam, which, as well as the electric lights, was everywhere to be had in this beautiful place.

And for all this, a mark and sixty pfennig, less than one ruble, and if one had not that to pay—well, if he was a Jew, there was a committee of wealthy Jews in Hamburg who saw that the money was paid to the steamship company, and if he was not a Jew—well, there was some mysterious way.

In the morning, they stood by and watched other immigrants coming in from the train, and by and by—about noon it was—they were all told to get ready to leave for the steamer. That was the announcement that thrilled them. Somewhere in the river below, the ship that was to take them to America was even then waiting.

In the Morning, They Watched Other Immigrants Coming In from the Train. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fd04518b

Hurriedly they gathered their bundles together and made ready the children, seeing to it that all the little ones got into their stockings and shoes, except of course those that had no socks nor shoes to get into.

The company's band was playing lively airs while they were assembling. It Was this same band that had played to them in the yard the day before, that played every afternoon in fact. Now when they were about to leave for the steamer, this lively band helped to put heart into them again.

It was American music they were playing, something that would tempt a lame man to hop along bravely. To the marching music of that band, they left the beautiful Auswanderer-Hallen behind.

The company was kind to them again. A wagon with two healthy horses came to take all their more cumbersome bundles. But there were some who, trusting no wagon, preferred to take their bundles on their backs, and they did so.

Out they went, across the long bridge above the Elbe, down the dark quay and aboard the tender—the little ship. Down the river, the tender took them, past the great vessels, which, now that they were close to them, looked greater than ever—more magnificent than anything they had ever heard or been told of—as high as a synagogue were some or a church, and as long as a village street.

A Tender Takes Immigrants Down the River. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fee15e3b

And such chimneys out of them! Vas it in one of these immense things, they were to cross the vast sea? Surely no waves could ever sink them? But they had been sunk. So? What storms there must be on the ocean!

Once more, they went ashore, and again it was a surgeon who looked at doubtful eyes. Back again to the tender by way of a gangway, where they were rushed along and counted like so many sheep, down the river again, down past the great ships —such a lot of great ships!—until to their own particular great ship they came, at last, none of them all more substantial than she. They had to look almost straight up in the air to see all of her.

Then it was more shouting, more ropes, more hurrying—would there never be an end to the hurrying? But aboard, they were at last. Amid shouting and churning and heaving of ropes, they were aboard at last—crowding and bumping, up the gang-plank and down the extended deck, and at last below.

Amid rows of tiered bunks packed close together they were now. Still, they had come to a place of rest at least, and dropping their bundles and thankfully sitting on them, they heaved sighs all around and listened to the music that came floating down to them from the upper deck. Most significant—though not to them—was that music.

The ship's band, while they were piling aboard, was playing " The Star-Spangled Banner." These poor immigrants did not know what national anthem it was, did not know that it was a national anthem at all, this story of an incident in connection with the flag that to them was soon to stand for so much, and to their children after them, if their blood was not water, so very much more.

That trip with those Russian immigrants was not carried beyond the lower decks of the German liner as she lay at the mouth of the Elbe River. However, we know that in good time they reached New York.

Possibly all things were not to their entire liking. Still, it was assumed that our steerage passengers were carried across the ocean with as much comfort or lack of discomfort as could be reconciled with a fair profit on the amount of passage money paid in.

Considered merely as a business proposition in the case of a company with a plan big enough to construct the Auswanderer-Hallen at Hamburg for $350,000, one might reasonably assume that, and feel safe in jumping over to Havre, France, there to observe the treatment meted out on the ocean trip to another great body of immigrants.

Immigrants' Waiting Room at Hamburg. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fd51931f

The type of immigrant that is particularly interesting in the United States because of the strange customs and the new tints he is adding to the nation's life comes from southern Europe and Asiatic Turkey, from the Mediterranean countries of Asia and Europe and from southern Russia, Austria, and France.

A Type of Immigrant. Illustration by M. J. Burns, Scribner's Magazine, November 1902. GGA Image ID # 14fdd78e3d

Havre offers a quick route for the greater part of southern Europe, and so these countries choose to shoot their emigrants through here. From Asiatic and European Turkey, from southern Russia, from Greece, from Austria and Italy they start for us; by way of Smyrna, Constantinople, Piraeus, and Naples, through Moscow, Vienna, and Berlin they come and increasing as they come so that when they reach Paris, where all rail routes converge, there is a vast army of them.

Here they are gathered like lost tribes and set right on their circuitous journey. At Havre, they, too, are switched on to stone piers, passed through physicians' hands, and later hustled into the holds of great ships. Eventually, all are dumped into New York, where the wide-meshed Immigration Bureau, taking charge, sifts them through Ellis Island and discharges them on to the country.

One of the biggest liners sailing out of France, with 800 steerage passengers aboard, was selected for observing the manner of handling steerage passengers bound for America.

A firm conclusion reached after the experience of that trip is that an immigrant of this class has to put up with much unnecessarily unpleasant treatment:

First, simply because he is an immigrant, and therefore in judgment meriting it; and, secondly, because, being what he is, he has not yet learned to protect himself.

The picture conjured up by the term " immigrant " in the minds of those who have their care en route is not at all the color of the vision that arises before us with the word.

Here in America, we have a notion of a band of earnest, and it may be, if we are uncharitable, worn and unwashed men and women with families (though the family and the washing are really outside for the moment), hurrying from hard conditions of life—scant, underpaid labor, ignorance, oppression, misrule—pressing on to what they must conceive to be a bright land of promise, or they would not be rushing hereto a glorious young country, where all men are free and equal and all that sort of thing.

But the man who has to see that these immigrants are given food and bunk and that they do not fall sick below, has no such fancies his sympathy, he will tell you, is not for the immigrants, but for the country that is to get them.

Those in charge of the immigrant from southern Europe will tell you that he is not a desirable creature. They have handled many, many thousands of his kind, and they should know something of him now.

The company transports him, it is true, but as to that, he is freight, freight of good profit. The company would take freight to the highest degree distasteful if so be the rates were paid.

Indeed, yes, it is business. There is a substantial profit in the immigrant—oh, yes—but as a fellow-passenger, he is—oh, well, repulsive, repugnant, or whatever you say in your language.

He has such ways, such habits that are—well objectionable, would you say? He is neglectful of the most ordinary civilities, he is slothful, the immigrant is boorish he is—m-m—dirty.

And his manners b-r-r h! He is—Oh, what is he, not that this is distressful? It is the steerage stewards that tell you this.

They are pleasant little fellows, these stewards—courteous, cheerful, entertaining, even desirous (after you have attended to the matter of the tip) that you will take with them an extra dipper of wine from their table after the others have gone.

Chemical, purple wine it is, but no matter, you like them already, and you feel that you will like them better before the trip is made. But even as they tell you these things, and even while you appreciate their kindness and good-fellowship, you also feel that there is much in their own attitude to set on edge the feelings of a self-respecting immigrant, who is made to understand from the first that he is low-caste aboard ship. He needs not the gift of intuition to discover that. It almost rises up and hits him in the face.

The poor immigrant may be deficient in many ways. He may not be given to a morning tub and to regular tooth-brushes. He may be unaware of the uses of many modem improvements, of the latest things in plumbing, of the last variation in court etiquette. Of many other curious devices, he is not cognizant.

He suspected it long ago, and every single peep into luxurious second-class quarters is strengthening lately acquired suspicions that he is missing some desirable things in life.

That he is really behind the age in many particulars is not to be denied. He would probably admit it to anybody who would present the argument in a speech that would not damage the little self-respect that still clings to him.

But it is slightly rough that before he heaves in sight at all, before his height, weight, complexion, or shape of the head is known, he is assumed to be an inferior kind of creature, a dull brute on whom consideration would be thrown away.

And there you have it. And from the time he crawls out of his bunk in the morning, until he backs in again at night and crawls out still next morning—he is " up against " the hard features of steerage transportation.

If the servants of the company would but be kind to him, the immigrant's lot would not be so bad; but the servants of the company are not helpful to him. The stewards, quoted in a previous paragraph, really come nearest of all to extending him kindness aboard ship. (Possibly that is because they have the feeding of him.)

One might think that the ship's crew would be disposed of above all others to show sympathy for the immigrants. But it does not seem to run that way. Steerage and crew, as things go ashore, would be rated about the same caste. If it is a question of social standing, as conventionally measured, neither has much the advantage—as a class.

It may be true that the immigrant has little use for a sailor-man. But as it lies principally with the ship's people whether relations are to be friendly or otherwise, and as the crew generally prefer to squelch any advances on the part of the steerage, with the crew should rest the blame.

Now should these same immigrants make the trip back, after having lived here ten, fifteen, or twenty years, they will look for a different state of affairs. They will resent the old treatment, and if the ship's people persist, they will complain, even when they suspect the complaint will never reach head-quarters.

The difference between the green immigrant and the same man after he has lived in the United States for a decade or two is well known to steamship servants. It is everyday talk below deck on ocean liners that steerage going west and steerage going east are not to be handled in quite the same way.

The moral of it all may only be a logical deduction from the social evolution which has for a long time now been considered an inevitable, or possibly indispensable, part of our better growth, and which—or something like it—will enter into our growth for a long time to come.

It is likely that in the future, this social development may take on less violent transitions than some we have seen in the past. However, that is open to free argument.

The average immigrant that comes here and soaks in our public life during a residence among us of ten or twenty or thirty years is a vastly better creature, take him all round, than when he came to us a timorous immigrant.

He is aware of the change, rates himself the higher for it, and expects that others will rate him higher also, and, without stopping to reason it out, the others do so.

Connolly, James B., Illustrated by M. J. Burns, "In the Paths of Immigration," in Scribner's Magazine, Volume XXXII, No. 3, November 1902, pp. 513-527.