Emigration from the German Ports of Hamburg and Bremen

History of Emigration from the German Ports of Hamburg and Bremen with a discussion of how the two major steamship companies competed with one another for the immigrant trade.

Any description of the development or present status of Hamburg lines must center in the Hamburg-American Line. Not only is it the largest steamship company in any country, but it comprises half the ocean shipping of Hamburg, affords a far larger proportion of her connections with oversea and is actively interested in all the other larger lines excepting the German Australian Steamship Company.

The Hamburg-American Line was established in 1847; its official name is the Hamburg- Amerikanische Paketfahrt Aktien-Gesellschaft. The initial letters of the official name spell the word Hapag and it is as Hapag that the line is popularly known.[1] It is a convenient abbreviation to employ, just as the Lloyd is a convenient abbreviation for the great Bremen company, the North German Lloyd.

The Hapag was founded in 1847 to prevent a further concentration in Bremen of the American mail service, as well as imports from America of cotton and tobacco and exports thither of German emigrants. Bremen had had a packet sailing line to New York since 1826.

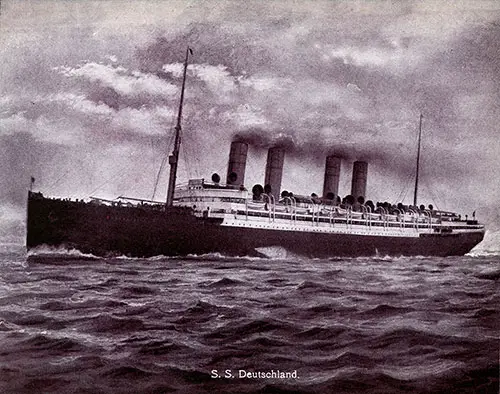

The Hapag began business with three copper-bottomed sailing ships of together 1,600 register tons, and with a capital of 460,000 marks. The “Deutschland,” which left on her first voyage to New York on October 15, 1848, was of 717 tons register and had room for 20 cabin and 200 steerage passengers.

Until well into the nineties the transportation of steerage passengers played the chief role in the New York business of the Hapag and the Lloyd and its profits enabled those companies to build up their fleets. In the early days of the Hapag there was little return freight to America to exchange for the bulk products we sent Germany.

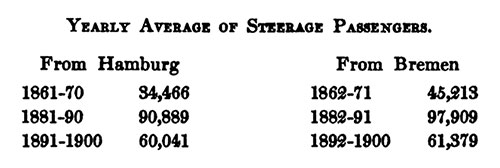

But Germany did send us men. The average number of steerage passengers brought us by the two German companies in the years 1860-1900 was as follows:[2]

Average Steerage Passengers from Hamburg Compared to Bremen During Selected Years 1861-1900. GGA Image ID # 1413ad196f

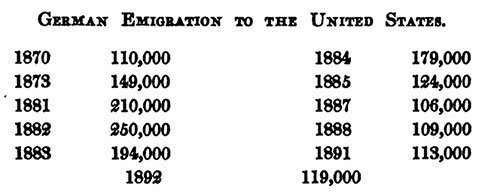

German emigration to the United States, in those years since 1870 when it exceeded 100,000, was as follows:[3]

German Emigration to the United States, 1870-1892. GGA Image ID # 1413c7c12c

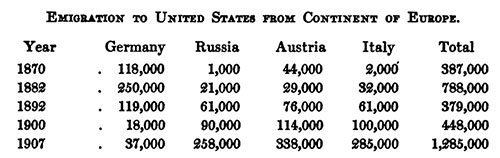

In 1895 the German emigration dropped to 82,000 and has never since reached 50,000. But, as the German emigration died down, the Hapag and Lloyd concluded a treaty with the other continental transatlantic lines, whereby the German lines were to have the transportation of East European emigrants to the United States.

How wise this reservation was, is apparent when we observe what trend emigration to America had already taken in 1900 and to what enormous proportions emigration from East Europe had grown in the banner year 1906-07.[4]

Emigration to the United States from Europe for Selected Years Between 1870 and 1907. GGA Image ID # 1413ed7f7c

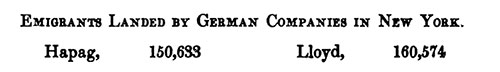

The part the German lines play in the transportation of these hordes is exceptionally large. In 1907 they landed in New York from their German and Italian services the following number of emigrants:

Emigrants Landed in New York by the German Steamship Companies.[5] GGA Image ID # 141409098a

Their nearest rival was the Cunard Line, which in 1906 landed in New York from its British and its Mediterranean services 107,790 steerage passengers.

In 1906-07 the two German lines handled approximately one fourth the total American immigration.

Assuming an average fare of $86.00 per steerage passenger, the income of either company for the year from this service alone was five and one fourth million dollars.

Germany now exports largely to the United States, but her exports are primarily manufactured articles of high specific value and small bulk. The ship room occupied by American goods cannot be filled for the return voyage with German goods.

Ships are so equipped that certain decks may serve as cargo space for the east-bound trip and in Bremen and Hamburg be transformed into steerage quarters for the west-bound.

The fact that emigrants can be counted on as return freight has had a great influence on the inducements that the German companies could offer in freight rates from the United States to the continent. It accounts, in large measure, for instance, for the concentration in Bremen of the European trade in American cotton and tobacco.

The Hapag’s three sailing vessels of 1848 maintained a monthly service with New York, averaging forty-one days on the ocean west-bound, twenty-nine days east-bound.

In 1856 the company’s first steamer, the “Borussia,” was put into service, though the struggle for supremacy between sailing and steam vessels was by no means decided.

Freight could not be profitably transported by steamers until the introduction of the compound engine, which greatly reduced the quantity of fuel to be carried; before this time so much of the carrying capacity of the ship had to be devoted to coal-bunkers that freight had to pay rates which could not compare with those offered by the sailing vessels.[6]

But, as we have seen, the North Atlantic trade was preeminently a passenger trade. The saving in time which the steamers afforded—though slight at first—their greater steadiness and safety, conspired to give them the preference in the Hapag’s fleet. By 1867 the last of the sailers was sold. The Lloyd, founded in 1857, never possessed a sailing vessel.

Business for the Hapag was excellent in the decade 1860-70. Especially was this true for the years 1865- 66-67. The American Civil War was over and commerce was renewed with the Union, which needed supplies to repair the devastation that had been wrought.

The American merchant marine had been destroyed and foreign carriers came into its heritage. In the three years 1866- 66-67 the Hapag distributed 20, 20 and 16 per cent in dividends, respectively.

The year 1871, when the Empire was formed, saw the Hamburg lines multiply. The Hapag instituted a service to the West Indies; in the same year the Hamburg South American Steamship Company was founded to ply between Hamburg, Brazil and the la Plata.

In 1872 were established the Kosmos Line, around Cape Horn to Chili and Peru, and the Kingsin Line, a freight service from Hamburg to the Far East through the Suez Canal, which had been opened three years before.

The panic of 1873 set in and held up further advances. In 1873 the Hapag fell into a rate war with the newly founded Adler Line, established to partake in the profits of the transatlantic trade. It was a war that lasted three years.

The Hapag, which had paid 12, 16 and 20 per cent dividends in the years 1871-73, paid no more dividends until 1878. The contest ended in 1875, when the Hapag unwillingly purchased the Adler steamers.

In order to do this, the company’s capital was increased from sixteen and one half to twenty-two and one half million marks; it had to be scaled down to fifteen million in 1877.

The Hapag was left with a fleet out of all proportion to its needs, into which it could not grow for years to come. Yet the cloud had a silver lining. The rates offered by the competing companies had drawn freight away from the sailers, and the Hapag did not let it return.

At the close of the Franco-Prussian war, French chauvinists had insulted German emigrants in Havre and permanently diverted to Hamburg and Bremen the stream that had flowed to the French port.

Moreover, Hamburg was learning from Bremen how to and attract emigrants. Early in the century Bremen had recognized the future of the emigrant trade.

There were enacted in Bremen severe regulations against ill-housing, underfeeding, swindling or otherwise maltreating emigrants, — matters to which Hamborg was too long indifferent. This policy gave Bremen on the entire continent a reputation that still endures and is worth to her thousands of emigrants yearly.

Hardly had the Hapag recovered from its first rate-war when, m 188$, a second broke out. The new Edward Carr line and the old Hamburg shipowner, Robert Sloman, who had instituted as early as 1849 an emigrant sailing line to New York, united to form the Union Steamship Company, which fought the Hapag’s line to New York.

The struggle was terminated in 1886, when the Hapag and the Union companies combined their schedules. In 1888 the Carr steamers were purchased; the 1886 agreement with Sloman ran on until 1907, when his steamers also were bought.

This second rate-war gave the Hapag its present brilliant manager, Albert Ballin, who was taken over from the Carr line; and it taught the company the raine of timely compromise in ocean warfare.

Since then the Hapag has been the prime mover in many of the combinations that go to make up the complicated system of agreements, pools, defensive and offensive alliances, and fusions that prevail in ocean shipping today.

From now on the Hapag had a clear field. Foreign trade grew -- Hamburg’s hinterland demanded increased grain, meat and other foodstuffs, fertilizers and fodder and the raw materials of industry; it exported more and more potash, sugar and manufactured goods as Germany became established in the markets of the world.

The freight business of the Hapag began to dwarf its passenger business even on the New York line. In 1891 the Hamburg Hansa Steamship Company was bought up and its lines to Montreal, Boston and Philadelphia turned over to the Hapag flag, which was already serving Baltimore.

In 1898 a freight line was established to China and the Far East and the Hamburg Kingsin Line (1871) of the same destination was purchased.

The “Deutschland,” the Hapag’s only express steamer, paid for with the proceeds of the sale to Spain of obsolete Hapag liners, at the time of the Spanish-American war. She is being built over into a pleasure cruiser, the “Victoria Luise.” GGA Image ID # 14141cec29

In the meantime other lines had not been idle. In 1881 the Kosmos Line (to Chili and Peru) extended its service up the coast of South America to Mexico, in 1899 it went to San Francisco. In the following year, the Hapag made the Kosmos Line let the Hapag share its extremely profitable service to West America under an agreement whereby either company supplies a certain proportion of the total number of steamers dispatched per year.

Profit and loss are distributed according to the tonnage of steamers which each company supplies. It is a common form of agreement in Germany and one by which the all-powerful Hapag has come to have a share in nearly every other profitable steamship company in Hamburg. The Kosmos also has a line from Genoa to West America and in the course of its career has bought up the rival Hamburg Pacific Steamship Company.

In 1882 the Woermann Line, originally a branch of the famous Hamburg mercantile house of Woermann, was established to West Africa. Since 1907 the Hapag has also shared this service. The Lloyd and the Hamburg- Bremen Africa Line had formed a similar partnership.

In 1907 they entered into a “community of interest” (Interessengemeinschaft) with the Hapag and Woermann. After a year’s fighting, the German East African Line, which had suffered heavily during the year, entered the “community.” Thus all German lines to Africa are united.

When in 1910 the Hapag and Woermann decided to establish a direct connection between New York and West Africa, they announced the following program:[7] “The steamship Carl Woermann will begin in December a new and direct service between this port and the west coast of Africa, under the joint auspices of the Hamburg- American and Woermann lines.

Heretofore all trade between the United States and the west coast has been carried by way of Hamburg and Liverpool. The Canary Islands will be the first port of the service. The ships will call at a hundred or more places on the west coast. Very little money will be used.

The ships will exchange oil, tobacco, flour, machinery, cotton goods and food products—practically every ship will be a department store afloat—for mahogany, palm oil, rubber, ivory, cacao, and copper.

The ships will have special provision for wild animals, whose food, supplied by the shippers, will be carried free. It will cost a shipper $250 to bring an elephant to New York; $200 for a giraffe; $100 for a lion, tiger or leopard, and $25 for an ostrich.” To the uninitiate, the fare for giraffes seems particularly reasonable.

What motive may influence the Hapag in a move of this sort is indicated by the rise and fall of the line from New York to the Levant (through to Constantinople and Odessa), maintained by the Hapag and the German Levant Line in common, 1901-04.

The considerable traffic from New York to the Levant, transshipped at Hamburg, was threatened by the prospect in 1901 that a direct Russian or Italian line would be established.

So the Hapag and the German Levant Line instituted the direct connection themselves and continued it for three years. In 1904, when conditions had changed and there was no longer fear of Russian or Italian competition, the line was withdrawn; New York goods for the Levant were again brought to Hamburg and transshipped there to the steamers of the German Levant Line.[8]

In 1888 the Hamburg-Australian Steamship Company came into life. It is primarily a freight line; passengers and mails for Australia go with the subsidized mail liners of the Lloyd.

The Hapag has no connection with the Hamburg-Australian ; there was long, apparently, an understanding between the Hapag and the Lloyd that Australia should be left to the Lloyd, in return for which the latter kept her hands off Africa.

In 1890 the German East African Line was established with a subsidy of 900,000 marks yearly, given to assure regular connection between Germany and her colony of German East Africa.

The Hapag and Woermann are now financially interested in the line. At first it ran through the Suez Canal and down the east coast as far as Delagoa Bay. Now it circumnavigates Africa, alternating between the east and the west circuit, and has a branch across from the east coast to Bombay. Its subsidy amounts to 1,350,000 marks per year and a considerable part of its service is performed by the Hapag.

[1] In view of the luxury that prevails on the company’s New York boats and the prices which passengers must pay for it, it is suggested that the initial letters mean, “Haben alle Passagiere auch Geld?” (Are all passengers well supplied with money?)

[2] Fitger: Die wirtschaftliche und technische Entwicklung der Seeschiffahrt, 1903, page 19.

[3] Thiess: Die Hamburg, page 86.

[4] Report of the Commissioner of Immigration in the 1907 Report of the Department of Commerce and Labor.

[5] 1907 Report of the United States Commissioner of Navigation, pages 146-7. The German companies were hard hit when the American panic of 1907 set in and ruined their emigration business for 1908. Emigration via Hamburg dropped to 78,808 in 1908; in Bremen it dropped to 74,626. (Nauticus, 1909, page 298.) In 1910, emigration had about regained its normal status. In the year ending December 31, 1910, there were landed in New York, by the three leading companies in the passenger and emigrant business, the following number of persons:

Cabin and Steerage Pastengert Landed in New York, 1910.

Figures of the Landing Agent of the United States Immigration Service, published in New York papers, January 11, 1911.)

[6] In 1866 Adolph Wagner wrote an article on Ocean Transportation in Rentsch’s Handwörterbuch der Volkswirtschaftslehre. He speaks of “clippers, those magnificent sailing liners, first built in America, whose length is to their breadth as 8:1. This relation* was formerly 3:1 or 4:1 in sailing ships. Hamburg clippers like the ‘Donau’ have made the trip from New York to Cuxhaven in 18 days, while good steamers do not get under 13 1/2 to 14 days and ordinary sailing vessels take 5 or 6 weeks.” Wagner thought that the steamers would eventually have the transportation of persons and package freight, while the sailing vessels retained bulk freight.

[7] New York papers, November, 1910.

[8] K. Thiess : Die Hamburg-Amerika Linie, page 34.

Edwin J. Clapp, The Port of Hamburg, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1912, p. 82-91.