Yank Weekly: 10th Mountain Division - 1945-04-06

These ski and boot troopers have learned how to get the maximum in mobility and surprise on the snow-covered slopes of Italy.

By Cpl. George Barrett YANK Staff Correspondent

Pfc. Alexander L. Cherkasky and Pfc. Robert L. Blome orient themselves with a map and a compass.

With the Fifth Army in Italy—The six-foot-three MP waved the German prisoner into the PW cage with his machine pistol. The Kraut’s fingers played nervously with the Ml-bullet hole in his right breast pocket. He turned around and said to no one in particular: “They look upon the war as though it were a sport. They are not tired at all. It’s all a sport with them.” He was talking about his captors.

The PW was one of 388 Germans captured recently in three days by the picked and specially trained “Ski and Boot Troops” of the 10th U.S. Mountain Infantry Division—the same outfit that- used to pose for all those snow pictures in the magazines and newsreels when it was training back at Camp Hale in the Colorado Rockies.

In a way the German was right. It sometimes seems as if the 10th regards this slow and punishing war in the Apennines as a part of a college winter-sports carnival. There are regimental orders decreeing undergraduate crew haircuts for every man and encouraging singing. Before the division began its drive on Mount Belvedere in late February—the first successful American offensive action in Italy since the cracking of the Gothic Line five months before— the divisional newspaper published the following:

“In case you’re worried about being able to keep that Luger or machine pistol you expect to take from Jerry, forget it Here’s a direct quote from the top: ‘I don’t want any souvenirs my men may get from a Kraut taken away from them. That Luger or burp gun belongs to that soldier and if he wants to trade it off for cognac or save it for his best girl until after the war—OK. It’s his, to do with as he sees fit. . . . It’s open season, and there are plenty of Lugers. Good hunting.’ ”

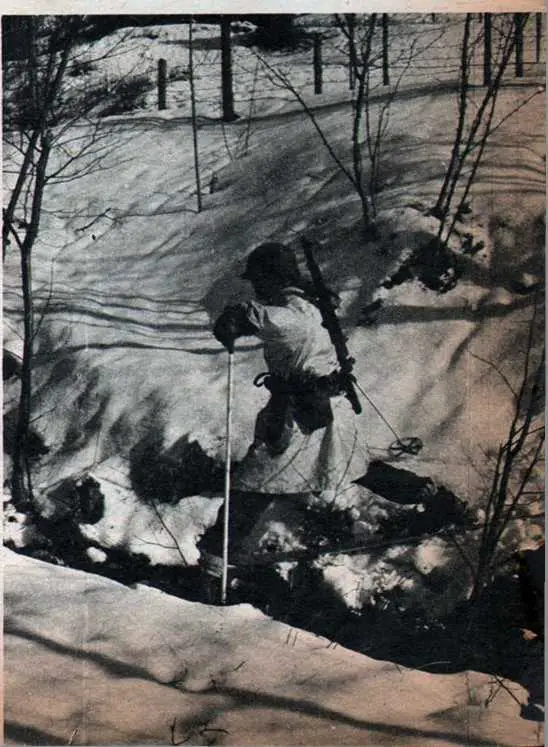

Pfc. William C. Douglas of Lake Forest, III., carefully makes his way across a mountain stream on his skis.

The next morning the 10th attacked. Climbing upward over sheer cliffs that the Germans had considered inaccessible and losing men in deep chasms and from dangerously high peaks, they took the strategic mountain which had been lost on two previous occasions. They stripped the burp guns and Lugers, and the periscopes, mortars and knives, from the dead Krauts and rolled the corpses down the mountainside.

“We returned with much booty,” said a GI in the 2d Platoon of Company A, 86th Mountain Regiment. “We took a victrola from a German dugout and carted it to our foxhole. Jerry had left a lot of A1 Jolson records, and we played them all night long after we took the top of that ridge. Oh, hell, there was nothing dangerous abouUmaking all that noise. They knew we were there anyhow. Incidentally, their butter is lousy.”

The winter-carnival atmosphere in the 10th is something that might be expected. After all, Walter Prager, the Dartmouth ski coach, is a first sergeant in the 87th Mountain Regiment. Friedl Pfeiffer, U. S. slalom champion and ski instructor at Sun Valley, Idaho, is one of the buck sergeants. Torger Tokle, the national ski-jumping champion, is a teclf sergeant. Pvt. Herbert Schneider, scout-observer in the 86th Regiment’s I and R Platoon, has spent his whole life at winter-sport resorts; he is the son of Hannes Schneider, the famous Austrian ski instructor.

And most of the other-men are members of the National Ski Association, which helped the Army organize its first Mountain Infantry battalion in December 1941, at Fort Lewis, Wash. One of the few soldiers in the 10th who didn’t spend all their free time before the war at winter-sports resorts and ski tournaments is the division commander, Maj. Gen. George P. Hays, who flew here from France, where he had been commanding the 2d Infantry Division’s artillery, and took over the mountain outfit when it arrived from the States.

But Maj. Gen. Hays has another claim to distinction; he is one of the rare generals who are entitled to wear the Congressional Medal of Honor ribbon. He won it as a second lieutenant in the other World War.

Because the division was drawn largely from the social class of men who could afford the rather expensive sport of skiing in civilian life, it has more swank than the usual Infantry outfit. It is quite normal to hear one of its lieutenants say, “My platoon sergeant is a Princeton graduate, cum laude,” or to get challenged in its area by a sentry with a Harvard accent.

Back at Camp Hale, where they bothered about such things, the average AGCT of one of the regiments was 121, which meant that the dumbest buck private was eligible for OCS. If he did decide to take that step, the chances are it wouldn’t have gotten him out of the division. Most officer candidates from the 10th, because of their specialized mountain training, go right back into the division after they get their commissions. Nine of the current company commanders used to be enlisted men in the division.

The men of the 10th have been trained for every kind of mountain fighting, summer and winter—their stub-toed ski boots have heavy rubber cleats for rock climbing—but they are particularly effective in snow operations. As snow troops, according to one platoon leader, patrols of the 10th move “five tithes as far, four times as fast” as regular Infantry. Winter reconnaissance patrols by the 10th are likely to be more successful than I and R sorties by ordinary Infantry outfits because ski soldiers go higher and deeper into the mountains. If they are suddenly spotted by the Krauts at close range, they have the mobility to get out and away fast.

The 10th faces peculiar difficulties. It is not practical, for example, for skiers to carry their rifles at port in enemy territory; it takes two hands to use ski poles, and skiers must use their poles to climb high ground. Sometimes, under pressure, they have to fire their rifles with these poles still hanging from their wrists. The 12- pound skis and 2-pound poles make it important for the mountain trooper to streamline his movements. He will sometimes carry grenades fastened to his harness so the safety pin will be pulled out automatically when he yanks a grenade off to toss it.

A lot of the special equipment and tactics they cooked up back in the States in training, however, have been discarded at the front. They used to get superstreamlined mountain rations, but they now find that the 10-in-ls are just as good. They don’t bother to wear the white ski pants any more; the parka is just as effective for camouflage. Rifles were once painted white, but that is not considered necessary on the line in Italy. Special ski waxes are in the T/E but candles do the trick almost as well.

“We also discovered that the mountains here are a lot steeper and more wind-swept than those in the States,” one GI says. “Consequently we learned that we’d probably have to carry our skis a lot oftener than they carried us. On the other hand, the 4,000-foot altitudes in the Apennines are nothing compared with the 10,000 feet of the Rockies,' where we trained. It’s much easier to breathe over here. Also, during training back in the States we stuck pretty close to the cover of forests, but here we’ve found we’re not taking many risks if we move in the open, even in daylight, when we are in positions higher than the enemy.”

The men find their skis make noise on the hard snow crusts in the Apennines, and they have to take their boards off when approaching a Kraut position. On patrols, the mountain troops often require two scouts, one to break trail and another to do the scouting.

Everybody in the division is trained to move on skis or snowshoes in winter, even the chaplains. The mountain-troopers use the Arlberg technique of skiing. It is slower than the parallel technique but it provides more control on the turns and is a lot surer for soldiers carrying packs and weapons. They can move at 10 miles per hour if they have to make a fast get-away, and a good skier, using $11 GI skis, will cut over the snow at 25 miles per hour on some stretches. What with the back pack and the weapons they carry, this is considered pretty good by the same guys who in pre-war races thought 50 miles per hour was nothing and who made records of 80 miles per hour.

“Snow jeeps”—M29s, or weasels as they are usually called—are the all-purpose vehicles of the 10th. These amphibious tractors—all white, even to the leather seats—haul supplies, tow skiers and do generally on the snow what jeeps do on the dirt. With their tread they can go almost anywhere a mule can go.

The 10th is organized on the combat-team principle. The rugged terrain of the mountains requires that the various units be self-sustaining, because supplies are often impossible to transport. The division’s artillery pieces—75-mm pack howitzers—are broken down into sections and carried over the mountains on burros.

Gunners are trained to direct their fire against masses of rock and snow to create avalanches and engulf Kraut positions on the slopes below. These tactics are surprisingly effective. Division artillery officers point out that more than half of the casualties in Alpine fighting during the first World War were caused by avalanches.

Fighting in the mountains as a division presents the 10th with other problems. For example, the length of a battalion going single file up a mountain is four miles, but there may be more than 3,000 feet difference in altitude between the head and the tail of the column, affecting differently the speed and endurance of the men in its various sections.

The 10th probably does more climbing than skiing, and many of their sessions look like something out of a sea story when the GIs practice knots and lashings. They use the Tyrolean Traverse—a two-rope bridge stretched across crevasses and chasms—and improvise cableways to hoist jeeps and supplies up sheer cliffs.

Ropes are standard equipment and are given the same personal care that Mis get The lore of hemp has been drilled into the men of the 10th. They know that rope will lose 40 percent of its strength in nine months from age alone; that 40 percent of strength is lost when manila is bent sharply around a hook, and that any knot weakens a rope but no knot weakens it so little as the butterfly.

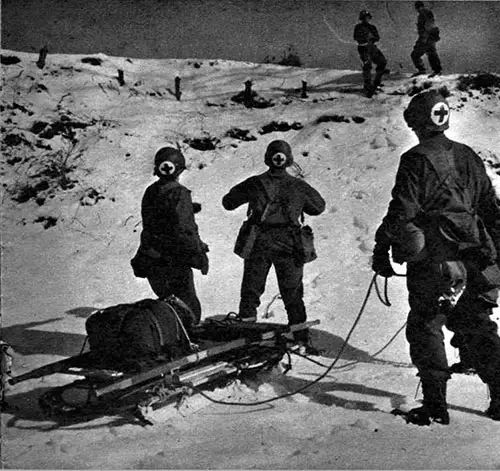

The mountain medics have had to alter ordinary procedure. “Plasma is useless to us,” one medic says. “It won’t flow in intense cold, and we don’t even take it along. In fact, we take very little with us except morphine and bandages. What counts in our work is speedy evacuation. Wounded men relapse into shock cases very feist in the cold at high altitudes, and unless we get them to a warm place soon they’re finished.

“The other day we picked up a sergeant in the snow and brought him to the station on a sled; it was fast work but he was in profound shock when we arrived. If we had not been equipped for snow transport the normal delay would have killed him.”

The medics are picked partly for their size; they are generally husky guys who have been given intensive training in mountain work. “It takes a strong man to get casualties out of mountain and snow areas," a medical captain points out. “Medics must be experts—in skiing, snow- shoe work, ropes and climbing—and they must work in large teams, for it takes six or seven medics to go after, say, one expert mountain- climbing infantryman and bring him back.”

The medics’ job is made harder by the fact that the ratio of walking-wounded to litter cases is sharply decreased in mountain warfare. Even slightly wounded soldiers cannot stand the heavy strain of struggling on foot down steep slopes and across cliffs. Special precautions must be taken with litter cases. Their helmets are kept on, for example, to protect them from falling rocks. They must be securely but painlessly tied onto the litter across the pelvis so they will not slide off while lurching over the uneven terrain.

"It’s hard to think of any operation of ours that I is not different from most outfits' tactics,” a captain said. “In general, 10th Division units are told that no matter how small they are they can at any time become independent commands. Mountains separate outfits very suddenly, and on the basis of knowledge that 10th Division troops are extremely alert and intelligent, SOP requires that junior leaders be given the ‘big’ picture. They are expected to do whatever needs doing to complete the over-all strategy.”

Then the captain quoted from the manual: “. . . There are no problems in mountain warfare which an aggressive and indomitable leader cannot solve. The movement of Hannibal’s elephants through the Alps, in the dead of winter, without aid of bulldozer, is ancient proof that insurmountable obstacles can be overcome.”

“That’s from our Army handbook,” the captain smiled. “It’s the kind of stuff we believe in.”

The mountain medics are skilled in getting sleds ond litters up steep slopes. The GIs in the foreground ore having a rope tossed to them to tie to the sled.

Pvt. Hubert Campbell of Eugene, Oreg., a 10th Division MP, stands guard over a bunch of prisoners just brought in by ski troops. He has an M3 machine pistol.