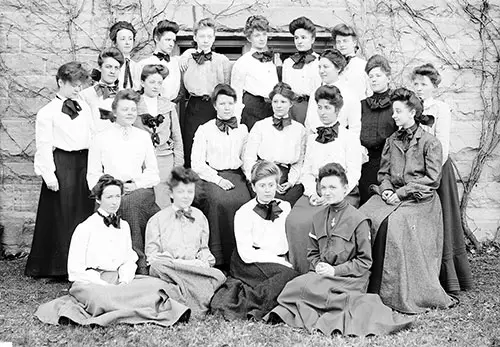

College Men and Women - A look back to 1903

Western College Class of 1905

THOUGH pursuing the same branches, with the same advantages and the same or similar instruction, the college-bred woman differs markedly from the college man.

This does not mean that her ability is inferior; on the contrary, her standing in the co-educational institutions has long since proved her the peer of the men with whom she works in classroom and laboratory. But her point of view, her methods and her mental processes are different.

As a rule, the college girl both during and after her four years' course is more conscientious, more to be relied upon, than her brother is. Sometimes she is morbidly conscientious, even to the injury of her health and peace of mind, though this type is not as frequent as in the early days of the higher education.

The college man takes things less seriously, looking at them from a broader point of view. Consequently, the very girls who outstrip him in scholastic competition often accomplish nothing of note in after years, while he goes ahead in his chosen business or profession, meets successfully the problems that arise, does original work of some kind and makes a name for himself.

It has always been claimed that woman is lacking in originality, and the college woman comes in for her share of censure on this score. While this is true to a certain extent, countless examples prove that womankind can and does do new things of all kinds, and the large and increasing number of alumnae who take the Doctor of Philosophy degree proves them capable of original thought and research.

The training of boys and girls from their childhood differs so decidedly in most households that it begins to divide their lives from that early period. Then, in all private schools, the methods vary, so that by the time the son and daughter of the same home enter college they are already widely separated in character and mind.

If they go to a men's college and a women's college, they enter very different environments, come under entirely dissimilar influences, and naturally develop more and more widely apart.

Compare the daily life of a student of Harvard, Princeton or Yale, with that of a Vassar, Bryn Mawr or Mount Holyoke girl. The independence, the lack of restraint, the scarcity of rules and regulations observed at the men's colleges, bring out the strength and breadth of the man's character, giving him capacity to grasp and deal effectively with the complexities of daily living and to achieve great and distinct results.

His is the practical training needed. President Hadley of Yale says: "As I understand it, the country wants three things from our universities. It desires, first, that they should furnish men who have the necessary training and habits to enable them successfully to pursue those calling; in life which require book knowledge as their basis.

It desires, in the second place, that they shall make discoveries, which shall help us in the international race for leadership, and shall enable the business of the country to be conducted in a more intelligent manner in the future than it has been in the past. It desires, in the third place, that they shall give to their students a training in public spirit which shall make them not merely producers or discoverers, but good citizens.

Though some advanced thinkers in social economics believe that women are needed and should go out into the world to do their share along the same lines as men, this theory has not yet penetrated into the women's college any farther than to make it regarded as a place where the young woman can prepare herself for self-support, either at once after graduation, if necessary, or to make ready for a future contingency.

Consequently, the boarding school atmosphere still pervades the institution of learning, and though student government prevails at many of them, it is only with the approval of the powers that be, and any innovation in the way of liberty is frowned upon.

However, many of the old-time restrictions are entirely done away with, and the feminine collegian of today does not even know of the many ways her primitive colleague was hedged about.

This seclusion and supervision tend toward the ideal, and the youthful alumna goes forth from her Alma Mater with high aspirations and those firm principles that have become traditional; but she is not always as well equipped as her more practical and rough-hewn brother for what lies before her in the workaday world, and she must readjust herself more or less.

The woman student of the co-educational university lives to a certain extent in the freer environment created by the men, and profits by it. In classroom and laboratory her opportunities are identical with the men's, and she imbibes something of the surrounding influences.

She participates in class affairs, too, and usually in social and dramatic events. But if she rooms in the women's dormitories she must expect a different life from that of the men, and she is excluded entirely from their freedom of life and boisterous, rollicking fun.

A Cornell girl, whom was put the question: "Should you prefer to be a man or a woman?" replied "Of course I really prefer to be a woman, but when I see how much more the men here are allowed to get out of life than we girls, it sometimes gives me lurking desire to be a man."

Yet, the college man and the college woman have many interests in common, and for this reason so often marry. ·heir mental training and acquiring of knowledge place them both on the same intellectual plane and tend to make them both enjoy the same pleasures and diversions.

Then, they are both imbued with college spirit, a quality which makes them lore akin than seems possible to the uninitiated. They both have that love of pure fun and that sense of humor which belong to college existence, and if they chance to possess any little weakness or foolishness, it is driven out by the good natured though sometimes heroic treatment of their fellow-students.

It is interesting to note some of the influences that shape the minds and characters of the young men and women at their respective colleges. The president and members of the faculty always impress their students with their own individuality; a man like President Eliot of Harvard, or a woman like President Woolley of Mount Holyoke, creates a feeling of respect and admiration, and both consciously and unconsciously to themselves the students are favorably affected and uplifted.

It is so, too, with the professors and instructors, who, while influencing the character by their personality, develop the brains and intellect through their lectures and other methods of instruction.

Books always play an important part in the life of everyone who comes in contact with them, and at college they are the centre about which all else revolves-not only text-books, but books of reference, of travel, biography, history, poetry and fiction so abundantly supplied in library and reading-room.

The annual Yale-Harvard debating contest, with the practice that precedes it, is one of the potent and interesting factors, and is typical of in intercollegiate celebrating among all the universities. The custom is not general among the women's Institutions, but is likely to be in time, as it has been tried, and numerous local celebrating clubs and societies with interclass contests are paving the way for it.

Dramatics forms a feature everywhere. Harvard's Hasty Pudding Club, the Masque at Cornell and similar organizations have brought out powers that otherwise might have remained latent forever, while the Shakespearian plays alone, so popular at all the women's colleges, are an emphatic educational force.

Dancing is one of the most recent innovations, though at some of the women's colleges it has been practiced for several years. Yale has introduced it this year and the large classes prove its popularity.

Dr. Anderson, director of the Yale gymnasium says: "In what we are trying to do at Yale I believe lies a future for physical education. We are starting in with simple movements; taking. up the jig and leaping dance. Later we expect to try some more advanced dances.

These will help the student to learn how to make a good appearance on a stage, should he be a public speaker, and to carry himself well generally." One reason why this novel method is being taught at Yale is the resthetic one.

It teaches ease and grace, control of muscles, easy movements and conservation of energy. Physiologically it develops the heart and lungs. Anatomically it-develops the machinery of the body, gives spring to the instep and pliability to the knee, ankle and hip joints.

All the colleges have their traditional customs, such as Yale's Rush Night, Bottle Night, Omega Lambda Chi Night, and the observance of Washington's Birthday, when the sophomores are for the first time permitted the dignity of a high hat and cane. The freshmen always interfere with them, with riotous results and a great deal of fun.

The Brown University men have a tradition a little on the same order, when on the first day of the Spring term the seniors inaugurate their wearing of cap and gown, and, cutting the first recitation after morning chapel have a glorious time on the campus in which the under-classes join, singing, yelling, parading about and cutting all sorts of antics.

Corresponding to these jolly capers some of the girls' colleges have such celebrations as senior hoop rolling, rope jumping and other sports on May Day, senior" howls," freshman initiations, and sophomore larks.

Hazing is not so much practiced at the men's colleges as in the olden times, but there is still some of it, and the girls do a little of it, though in a mild way. The welcome to the youthful novice is a very cordial one and has very little that answers to it among the men. She is feted and feasted and overwhelmed with kindness and attentions.

A far-reaching influence over many undergraduates of either sex is the example of many students working their way through college, wholly or partly. This is a more common episode than is generally known and does not count against the student wage-earner, for, in most instances, character and personality more than counterbalance the lack of means.

At the University of Chicago where self-support is so largely entered into, one is quite out of the fashion who does not undertake some form of work. Naturally a much broader field is opened to the men than to the girls, who are hedged about by the conventionalities,

Harvard is called the "rich man's college," and yet it exemplifies the statement that" no man with any grit, gumption or determination need go without a college education, however poor he may happen to be." It has been said that furnace work has helped pay more than one man's way through the Crimson University. Tasks of this kind are not within a girl's sphere, but many others are, and she manages to thrive on them.

Source: HALSTED, CAROLYN, "College Men and Women - A look back to 1903." in The Delineator: An Illustrated Magazine of Literature and Fashion, Volume LXII, No. 1, July 1903, Pages 138-139.