Evolution of the Steamship

- 1901 Article by Maximilian Foster

The evolution from Fulton’s little Clermont and seven miles an hour to the sixteen thousand ton ocean liner that averages twenty-seven miles an hour from continent to continent.

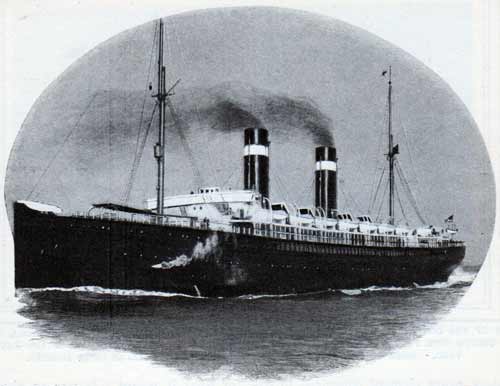

The American Liner St. Paul, 11,629 Tons, 20,000 Horse Power, 535 Feet Long, Built At Philadelphia, 1894

Man, in the beginning of his works, is a modest creature -- no more ambitious, perhaps, than the polyp that strives obscurely, yet in the end erects a vast monument to its toil and perseverance. Consider man's miracles upon the sea, and then look back into the lost ages when the first timorous navigator dared the waters in his coracle. A skin or a sheet of bark shaped and fixed upon wooden hoops -- in this he ventured forth, appalled, no doubt, at his vast undertaking, and with no imagination of what he had brought forth for future ages to develop. But, nevertheless, in this vague shape began the wonders that now walk the deep.

From the tiny coracle to the sixteen thousand ton twin screw Atlantic liner is a leap that demands aid to the imagination. So is the leap from the one dead coral creature to the atoll or the wooded island. Almost as great is the jump from the deep-sea packet of the beginning of the century to the steamship that today shuttles between Sandy Hook and the Fastnet or the Lizard in something less than six days. Ages by ages, the atoll slowly rose towards the surface; and once its form lifted above the waters, every element conspired to enlarge and to beautify the fabric. So it was with the ship. Ages after ages, it developed slowly -- then came steam!

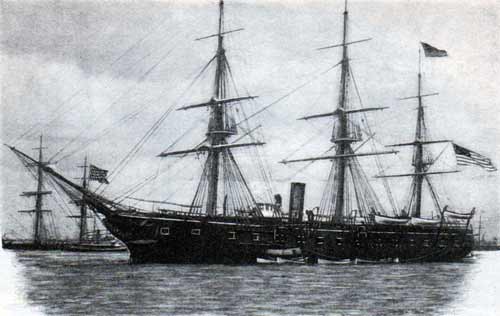

One of the Old Steam Sloops Of War-The Pensacola, 2700 Tons, Built At Pensacola, 1858; Served With Farragut At New Orleans In 1862, And Is Now At The Mare Island Navy Yard. Ships Of This Type Relied On Their Sails As Well As Their Engines.

Fulton and the Clermont, 1807

In less than a century a miracle has been wrought. In 1807, Fulton's Clermont -- the first successful steamboat ever built -- ran upon the Hudson. The world at large looked upon it as a pretty toy, a novelty, but had no conception of what it meant. It was an obscure beginning. Today, the Clermont might serve as an insignificant tender to an ordinary ocean liner, but as a preliminary, it made possible mighty things.

The statement that the Clermont was the first successful steamboat is used cautiously. Of late, there has risen a cult self appointed to tear down classic monuments. Its following will demonstrate by learned argument that there was no William Tell -- his name was Gustav Schmoeller; that Washington never crossed the Delaware -- it was General Lee; that Barbara Frietchie never existed -- her name was Anne Spruggins; and so on with dreary iteration. This same class will also tell you that Fulton was a mere pretender.

A Typical Ocean Going Side-wheeler, the Wyanoke, of the Old Dominion Line, Now Out of Commission -- Before the Introduction of the Screw Propeller, the Best Atlantic Liners Were Of This Type.

It is, of course, a historical fact that there were many attempts to propel craft by engines before Fulton. But Fulton, the American engineer, solved the problem. William Symington, in 1788, made the attempt on Loch Dalswinton, Scotland, and failed: In 1789, he tried and failed again on the Forth and Clyde Canal. In 1801, under the patronage of Lord Dundas, he built the Charlotte Dundas, but all his work came to naught.

In 1791, John C. Stevens began his experiments, which ultimately resulted in the development of the screw propeller. In 1804, he tried a twin-screw craft that failed to accomplish its inventor's intention. Then Robert Fulton's boat was launched, the next step in the making of the steamship.

Fulton's craft, in its way, was a wonder -- as inchoate and striving as the first locomotive. At a pinch, it could drive six, seven, or perhaps even as much as eight miles an hour; and this with a, clamor and discomfort that one may easily conjecture. Still it was a success.

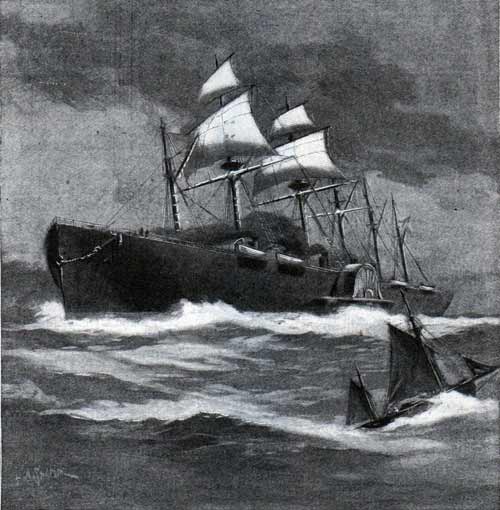

The Great Eastern, 19,000 tons, 690 feet long, built at Millwall, 1858, and equipped with both side wheels and screw. This huge vessel, for forty years the largest ever launched, was a complete failure, both mechanically and commercially.

Five years after the venture of the Clermont, the first successful English steamboat -- the Comet -- was tried upon the Clyde. She was of forty feet keel and ten and a half feet beam, and was built by John Wood & Company, of Port Glasgow, after the designs of Henry Bell. This, briefly, is the beginning of steam navigation in the United States and in Europe.

The success of the Clermont, and then of the Comet, demonstrated to the skeptical that after all there was something tangible in the steamboat. A year's trial sufficed to awaken commercial wisdom, and steamboats began to appear in many waters. In 1814, the Thames saw its first steamer -- the Margery, a craft of seventy tons and fourteen horsepower. Bristol, Manchester, and Leeds each built a nondescript, and a year later, the first steamship ever seen at Liverpool arrived from the Clyde.

In the United States and in Canada steam navigation quickly asserted itself. Both Stevens and Fulton developed their ideas; new boats were launched, and in a comparatively short time steam craft ceased to be a novelty. On the St. Lawrence, a passenger steamer -- the Accommodation, a copy of Fulton's Clermont -- plied regularly between Montreal and Quebec. She was eighty-five feet over all, and required thirty-six hours to make the passage. In 1813, the Swiftsure, a craft a hundred and forty feet over all, was launched, and succeeded in cutting down the time to twenty-two and a half hours. Thus, steam navigation was growing in every center of commerce.

A sectional view of the Great Eastern, showing her paddlewheel engines in the center of the ship, and her screw engines further aft.

The earliest steamboats -- of the type of the Clermont and the Comet -- were driven by engines of about four-horsepower, or about the same strength that one finds in the small naphtha launches of today. The engine cylinders were twenty-two or twenty-four inches in diameter; today they range as high as a hundred and twenty inches. In place of the Clermont's four-horsepower, the Deutschland, the latest maritime marvel, developed on one of her recent passages no less than 36,913 horsepower.

One can fancy the wonder of Fulton's followers at the Clermont's seven miles an hour. Last year, on here record trip from New York to Plymouth, the Deutschland was driven over the entire distance at a rate of 23.36 knots an hour -- or about twenty seven statute miles. But vast as the difference, it must again be pointed out that the clumsy, tedious Clermont was the one thing that made a Deutschland possible.

The Story of the Steamship - Contents

Ocean Travel Steamship Voyages

GG Archives

Transatlantic Ships and Voyages

- 1870 The Ocean Steamer

- 1877Steamship Lines - Transatlantic Passenger Traffic

- 1885 The Influence of Sea Voyages Upon Women

- 1897 Twelve Days on A German Steamship

- 1899 On The Ocean: From the "Yiddish" Poem of M. Rosenfeld

- 1899 The Therapeutic Value of Ocean Voyages

1886 Development of the Steamship

Ocean Passenger Travel (1891)

Ocean Steamships (1882)

1901 Story of the Steamship (1901)

- Gambling on Ocean Liners (1890)

- Crossing the Atlantic Like A Seasoned Ocean Voyager (1904)

- The Ethics of Ocean Travel (1904)

- Who's Who On Board - The Secrets in the Passenger List (1910)

- Early Days of Trans-Atlantic Navigation (1912)

- Wreck of the RMS Titanic - First Account (1912)

- How to Get To Australia (1918)

- Passengers Travelling Abroad Fewer in Number This Season than In 1920 (1921)

- Giant Ex-German Liners Weapons in Duel of I.M.M. and Cunard for Blue Ribbon of Atlantic (1921)

- Reclassification of Older Passenger Ships in Transatlantic Trade Coming (1922)

The Dry Years - The Eighteenth Admendment

Ocean Travel Topics A-Z

- Boutique Shops & Ship's Stores

- Ocean Travel Books

- Brochures - Steamships & Ocean Liners

- Correspondence, Shipboard

- Fleet Lists of Passenger Ships

- Ships and Ocean Liners Archival Collections

- Interesting Fun Facts and Factoids

- Journeys in Steerage

- Ocean Journeys

- Other Ephemera

- Passage Contracts and Tickets

- Postcards of Steamships & Ocean Liners

- Programs and Concerts

- Provisioning Ocean Liners

- Sanitation at Sea

- Ship Passenger Lists

- Ship Publications

- Shipboard Affairs

- Steamship Captains

- Steamship Crew

- Steamship Lines

- Ship Tonnage and Measurements

- Steamship Port of Calls

- Stowaways Onboard

- RMS Titanic

- Transatlantic Voyages

- Travel Guide (1910)

- Vintage Advertisements

- Vintage Ocean Liner Menus