The Subject of Ocean Lanes Used by Steamships (1911) - And Ocean Routes (1918)

The principal steamship lines of the North Atlantic have adopted definite fixed courses for their steamships in crossing the ocean, which are known as ocean "lanes."

Commanders of vessels are required not to deviate from these routes, except for the most urgent reasons. Among the objects attained by fixed adherence to established routes are: Prevention of collision between vessels proceeding in opposite directions, more certain and precise knowledge of winds, compass variations, ocean currents and weather conditions along the regular track, and prompt assistance to a ship in case of accident or injury. The established routes are as follows:

Eastbound

At all seasons of the year. From Sandy Hook light vessel to cross meridian 70 degrees west, nothing north of latitude 40 degrees 10 feet north.

From January 15 to August 2. From 40° 10' north and 70° west by rhumb line crossing meridian 47° west in latitude 41° north, and thence nothing north of the great circle to Bishop Rock.

From August 24 to January 14. From 40° 10' north and 70° west by rhumb line to cross meridian 60° west in latitude 42° north, thence also by rhumb line to cross meridian 45° west in latitude 46° 30' north, and thence by the great circle to Bishop Rock, always keeping south of the latitude of Bishop Rock.

Westbound

From January 15 to August 14. From Bishop Rock, on great circle course, to cross meridian 47° west in latitude 42° north, thence by rhumb line or great circle to a position south of Nantucket light vessel, thence to Fire Island light vessel.

From August 15 to January 14. From Bishop Rock, on great circle course, to cross meridian 49° west in latitude 46 degrees north, thence by rhumb line to cross meridian 60° west in latitude 43° north, thence also by rhumb line to a position south of Nantucket light vessel, thence to Fire Island light vessel.

Presbrey, Frank, "Approach to Naples," in Presbrey's Information Guide for Transatlantic Travelers, Seventh Edition, New York: Frank Presbrey Co., 1911: P. 72.

Note: In navigation, a rhumb line (or loxodrome) is an are crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle, i.e. a path with constant bearing as measured relative to true or magnetic north.

In A Related Article

Ocean Routes

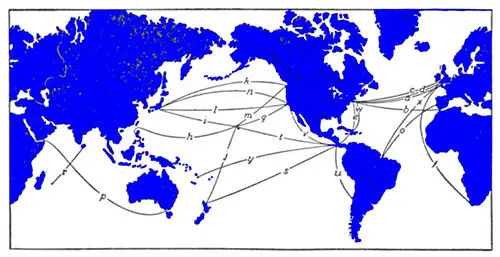

To a landsman journeying on the broad surface of the open sea, where, as Schiller says, there is nothing before and nothing behind but the sky and the ocean, the vast expanse of waters may indeed seem a trackless wilderness. Yet there are roads on the sea—ocean lanes, they are called—just as definitely fixed as those on land. In one of the main-traveled lanes no steamer is ever very far from another, as the map on page 4336 shows, but away from the regular track one might drift for years without being seen.

If you were given charge of a ship just outside of New York harbor and told to sail it to the Portuguese coast you would probably steer so as to pass through all points in a line directly cast. But a sea captain starting at the same time and steaming at the same speed would get there before you, for he would know a shorter route.

If, however, you were instructed to make for a point in the Bahamas directly south of New York, your rival could not pass you, for the compass route is the shortest. The reason for this difference is that, as we are taught in geometry (see Sphere), the shortest line between two points on the surface of a globe is part of a great circle (that is, a circle whose center is the center of the globe), and our lines of longitude are great circles, but our lines of latitude are not. A great circle line between New York and Portugal would run a little toward the north of east until the middle of the trip and then turn a little southward.

Ocean routes do not always follow the great circle exactly. Sometimes the way is blocked by islands or, as in the North Atlantic, there is danger from icebergs or fog. Usually eastbound boats follow a different lane from that followed by those westbound. c.h.h.

Consult Glbeme’s The Mighty Deep and What We Know about It; Ingersoll's The Book of the Ocean; Murray’s The Ocean.

PRINCIPAL ROUTES BY SEA

- (а) New York to Hamburg, 3,395 ml.

- (b) New York to Gibraltar, 3.204 ml.

- (c) New York to Liverpool. 3.079 ml.

- (d) New York to Southampton, 3,080 ml.

- (e) New York to Panama. 1,920 ml.

- (f) Cape Town to Plymouth. 5,948 ml.

- (g) San Francisco to Honolulu. 2,089 ml.

- (h) Honolulu to Manila. 4.645 ml.

- (i) Honolulu to Yokohama, 3.4 15 ml.

- (j) Honolulu to Auckland, 3,850 ml.

- (k) Vancouver to Yokohama, 4.230 ml.

- (l) San Francisco to Yokohama, 4,791 ml.

- (m) Vancouver to Honolulu. 2.410 ml.

- (n) Yokohama to San Francisco, 4,536 ml.

- (o) Para to Lisbon. 3,248 ml.

- (p) Aden to Melbourne. 6,310 ml.

- (r) Mauritius to Colombo, 2,090 mi.

- (s) Panama to Auckland. 4,180 ml.

- (t) Honolulu to Panama. 4,723 ml.

- (u) Panama to Valparaiso, 2,712 ml.

- (v) Los Angeles to Panama. 2,870 ml.

- (w) Boston to Colon, 2.092 ml.

- (x) Liverpool to Para. 4,010 ml.

- (y) Apia to Panama, 5,739 ml.

O'Shea, M. V., Ed., "Ocean Routes," in The World Book: Organized Knowledge In Story and Picture, Volume 6, Chicago: The World Book, Inc., (1918) P. 4335-4336