Saving the Transport Ship Covington - 1918

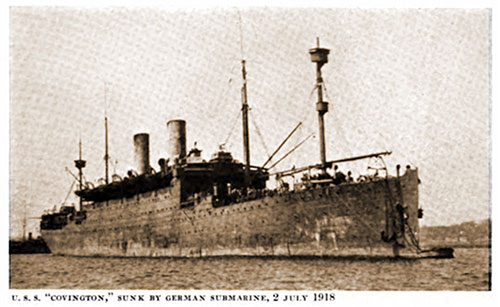

USS Covington, Sunk by German U-Boat Submaring on 2 July 1918. A History of the Transport Service, 1921. GGA Image ID # 1808edfbf0

The Covington, formerly the Cincinnati, a Hamburg-American liner of 26,000 tons displacement, was manned by a crew of 734 men and 46 officers, and had been provided to carry 3,500 troops. (Her capacity was later increased to approximately 5,000.) She made an excellent record as a troop transport and at the time of her sinking was on her sixth voyage, returning from Brest to New York.

The Covington, Captain R. D. Hasbrouck, U. S. Navy, in command, had sailed from France on June 30, 1918, in a convoy of eight transports, including the Lenape, Rijndam, George Washington, De Kalb, Wühebnina, Princess Matoika, Covington and Dante Alighieri.

Captain E. T. Pollock, U. S. N., commanding the George Washington, was the Group Commander, and on the evening of July 1st the convoy was proceeding in two lines under escort of seven destroyers, speed 15 knots, all ships zigzagging in two lines as shown by the accompanying sketch.

Strenuous Efforts to Save the "Covington"

On July 1st, 1918, at 9:15 P. M., the transport Covington, which had sailed from Brest, with several other large transports, was struck by a torpedo, the explosion throwing in the air a column of water reaching to a height above the smokestacks.

The engine-room and fireroom quickly filled, the ship lost headway and listed almost immediately. The order was given to abandon ship, and the boats and rafts were set afloat. The destroyer Smith stood close in alongside and took the men from the boats as' fast as they were filled.

An hour after the ship struck, the last of the crew left the Covington. In addition to her crew of 100 men, the little destroyer had aboard the crew of the Covington, nearly 800 men and officers. A salvage party was organized, ready to go onboard the Covington, and at 4:20 A. M., the British salvage tugs Revenger and Woonda arrived, and at 5:30 A. M., the American tug Concord reached the scene.

Preparations were made to attempt to tow the transport to the port. By 6 A. M., the three tugs had the Covington in tow and were making from five to six knots through the water. She was then listed about 20 degrees to port. A few minutes before 12 o'clock, the ship took an additional quick list of about 10 degrees. The list increased gradually until at 1:30 P. M. she was heeled to an angle of 45 degrees and was perceptibly settling slowly by the stern.

Ship Stood Vertically in the Water

USS Covington, Stern Just Going Under. A History of the Transport Service, 1921. GGA Image ID # 180940b293

At 2:30 P. M., the Covington began to sink rapidly. "It was an awe-inspiring sight," says the Captain's report, "as the ship quickly rose to a vertical position in the water, the after smoke pipe being clear when the ship was in a vertical position.

This gave a spectacle of about 430 feet of this magnificent 17,000-ton liner, standing as a shaft on the surface of the sea. The ship remained in this vertical position for a period of perhaps 10 to 15 seconds, then sank rapidly further in the vertical position, the bow disappearing at 2:32 P. M.

It was providential that all men had been removed from the ship before she rose vertically in the water. Had any men been aboard, they would undoubtedly have been lost. Had the ship sunk immediately or shortly after the ship was torpedoed, she would have sunk in the same manner as described above, and the loss of life would have been appalling."

The crew's discipline and the perfection of the drills brought about perfect order and ensured safety. There were no accidents. The final muster of the crew showed that out of the entire complement of 730 men and 46 officers, only 6 were lost; 3 fell overboard and were drowned while rigging out a boat; 2 were in a fireroom and were never seen afterward, probably killed by the explosion; 1 other man was missing and was probably drowned.

A few minutes after the ship was torpedoed, one guns' crew fired three shots at what was thought to be a periscope wake.

The ship went down with her colors flying.

"Mount Vernon" Saved by Good Seamanship

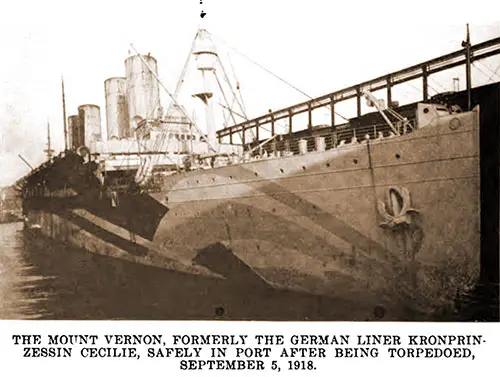

The USS Mount Vernon, Formerly the German Liner Kronprinzessin Cecilie, Safely in Port After Being Torpedoed, 5 September 1918. Our Navy at War, 1922. GGA Image ID # 1803cdae06

On the morning of September 5th, while about 250 miles from the French coast, the troopship Mount Vernon was attacked by a submarine.

Suddenly a periscope was sighted about 500 yards distant, and the starboard gun opened fire. The periscope disappeared, and a torpedo was sighted, headed for the vessel. It struck almost immediately, throwing up a huge column of water. The explosion killed Thirty-five men and 13 injured; the large number of casualties was due to the fact that the torpedo struck just when the watch was being relieved.

Captain D. E. Dismukes, the commanding officer, in his report, said:

"The explosion was so terrific that for an instant, it seemed that the ship was lifted clear out of the water and torn to pieces. Men at the after guns and depth- charge stations were thrown to the deck, and one of the 5-inch guns thrown partly out of its mount. Men below in the vicinity of the explosion were stunned into temporary unconsciousness.

"It was soon ascertained that the torpedo had struck the ship fairly amidships, destroying four of the eight boiler rooms and flooding the middle portion of the ship from side to side for a length of 150 feet. The ship instantly settled 10 feet increase in the draft but stopped there. This indicated that the watertight bulkheads were holding, and we could still afford to go down 2 feet more before she would lose her floating buoyancy.

A barrage of Depth-charges Fired

"The immediate problem was to escape n second torpedo. To do this, two things were necessary to attack the enemy and to make more speed than he could make submerged. The depth charge crews jumped to their stations and immediately started dropping depth bombs.

A barrage of depth charges was dropped, exploding at regular intervals far below the surface of the water. This work was beautifully done. The explosions must have shaken the enemy up; at any rate; he never came to the surface again to get a look at us.

"The other factor in the problem was to make as much speed as possible, not only in order to escape an immediate attack, but also to prevent the submarine from tracking us and attacking after nightfall.

"The men in the firerooms knew that the safety of the ship depended on their bravery and steadfastness to duty. It is difficult to conceive of a more trying ordeal to one's courage than was presented to every man in the firerooms that escaped destruction.

The profound shock of the explosion, followed by instant darkness, falling soot and particles, the knowledge that they were far below the water level enclosed practically in a trap, the imminent danger of the ship sinking, the added threat of exploding boilers—all these dangers and more must have been apparent to every man below, and yet not one man wavered in standing by his post of duty.

"No better example can possibly be given the wonderful fact that with a brave and disciplined body of American men, all things are possible. However strong may be their momentary impulse for self-preservation in extreme danger, their controlling impulses are to stand by their stations and duty at all hazards.

Facing Death, Men Did Their Duty

"In at least two instances in this crisis below, men who were actually in the face of death did actually forget or ignore their impulse for self-preservation and endeavored to do what appeared to them to be their duty. C. L. O'Connor, water tender, was in one of the flooded firerooms.

He was thrown to the floor and instantly enveloped in flames from the burning gases driven from the furnaces, but instead of rushing to escape, he turned and endeavored to shut a watertight door leading into a large bunker abaft the fire room, but the hydraulic lever that operated the door had been injured by the shock and failed to function. Three men at work in this bunker were drowned.

"If O'Connor had succeeded in shutting the door, the lives of these men would have been saved, as well as considerable buoyancy saved to the ship. The fact that he, though profoundly stunned by the shock and almost fatally burned by the furnace gases, should have had the presence of mind and the courage to endeavor to shut the door is as great an example of heroic devotion to duty as it is possible for one to imagine.

Immediately after attempting to dose the door, O'Connor was caught in the swirl of inrushing water and thrust up a ventilator leading to the upper deck. He was pulled up through the ventilator by a rope lowered to him from the upper deck.

Torpedo Exploded between Firerooms

"The torpedo exploded on a bulkhead separating two firerooms, the explosive effect being apparently about equal in both firerooms, yet in one fireroom, not a man was saved, while in the other fireroom, two of the men escaped. The explosion blasted through the ship's outer and inner skin and through an intervening coal bunker and bulkhead, burling overboard 750 tons of coal. The two men saved were working the files within 30 feet of the explosion and just below the level where the torpedo struck.

"It is difficult to see how it was possible for these men to have escaped the shower of debris, coal, and water that muse instantly has followed the explosion. However, the two men were not only saved but seemed to have retained full possession of their faculties. Both of them were knocked down and blown across the fireroom.

Their sensations were first a shower of flying coal, followed by an overwhelming inrush of water that swirled them round and round and finally thrust them up against the gratings above the top of the firerooms. Both of them, fortunately, struck exit openings in the gratings and escaped.

Saved Man He Thought Was Dead

"One of the men, P. Fitzgerald, after landing on the lower grating and while groping his way through the darkness trying to find the ladder leading above, stumbled over the body of a man lying on the grating.

At first, he thought the man dead, but on the second impulse, he turned and aroused him and led him to safety. The man had been stunned into semi unconsciousness and would undoubtedly have been lost if Fitzgerald had not aroused him. As a matter of fact, the water rose at once lo feet above this grating as the ship settled to the increased draft.

"Another interesting instance of the presence of mind and the effect of training may be cited. The attack occurred when all the men not on watch were at breakfast. One of the mess rooms is on the lowest deck aft, and it happens that there is only one exit to the compartment. Naturally, when the explosion shock came, the men at the tables made a rush for the exit hatch.

One of the men, Thomas F. Buckley by name, at first thrown to the deck by the force of the explosion, jumped upon one of the steps, turned, and yelled, 'Remember, boys, we are all Americans, and it's only one hit.'

The doctrine had been constantly preached to the men that one hit would not sink the ship if every man would do his full duty. This warning from Buckley was electrifying. All men immediately calmed themselves and went, not to their boats to abandon ship, but to their collision stations to save her."

Safely Navigated to Fort

Prompt and efficient work and skillful navigation were required to save the vessel after receiving the terrific injury. But the Mount Vernon was safely navigated to port, and all aboard, except those killed by the explosion, were saved. To drive off the submarine and prevent the firing of a second torpedo, a barrage of five depth-bombs was fired in one minute and ten seconds after the explosion.

Though 150 feet of the ship was flooded, and she was down to 40-feet draft, the vessel never slowed below six knots and within two hours was making two-thirds of her best speed on the way back to Brest. Among those aboard were 150 wounded soldiers who were helpless and whose rescue would have been very difficult had not the vessel remained afloat.

The saving of the Mount Vernon is attributed to the fact that the watertight doors were closed, the bulkheads were tight and held; that additional strength was gained by blanking off all air-port lenses with steel plate; and that there was an organization well-conceived and a system well carried out to meet the emergency.

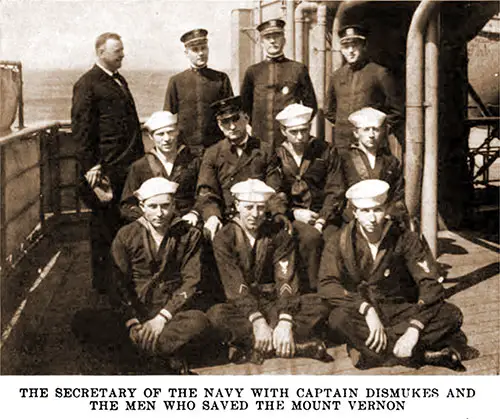

Secretary of the Navy with Captain Dismukes and the Men Who Saved the USS Mount Vernon. Our Navy at War, 1922. GGA Image ID # 1803e94ee6

Captain Dismukes and his crew were given the highest commendation by Secretary Baker, who was then in France; General Pershing and other Army officers, as well as naval authorities, and in a letter to the Captain, General George II.

Harries wrote:

"Congratulations on the seamanship, discipline, and courage. It was a great feat you accomplished. * * * The best traditions of the Navy have been lifted to a higher plane. What a thing it is to be an American these days! The olive drab salutes the blue."

Bibliography

Vice Admiral Albert Gleaves, USN, "Chapter VIII: Loss of President Lincoln -- Covington Torpedoed," in A History of the Transport Service: Adventures and Experiences of United States Transports and Cruisers in the World War, New York: George H. Doran Company, 1921.

Josephus Daniels, "Chapter VIII: Race Between Wilson and Hindenburg," in Our Navy at War, New York: George H. Doran Company, 1922.