Moving Our Troops Overseas - 1920

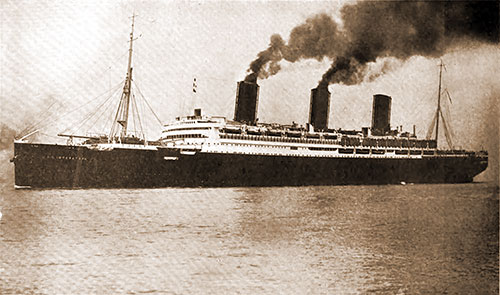

The Ex-German SS Imperator While in Transport Service of the United States. A History of the Transport Service, 1921. GGA Image ID # 18a7af52f1

The Official Figures of Uncle Sam’s Prodigious Effort to Increase the Allies’ Manpower

By Vice-Admiral Albert Gleaves, United States Navy

In the middle of April 1917, the condition of the Allies was desperate; General Nivelle’s offensive of April 16th had been lost to France with disastrous consequences; the Russian revolution had taken place; and conditions in England were desperate.

The morale of the French Army was at lowest ebb, and British supremacy of the seas had been challenged by the U-boat. The United States had declared war April 6th but had not intimated that she would take any active part abroad.

Indeed, her war preparations indicated a defensive attitude, although it was evident that moral support alone would afford but little comfort to our Allies. The urgent need was for men and guns to reinforce the hard-pressed French and British armies in the field.

In this crisis Great Britain and France sent commissions to President Wilson to urge our immediate and active participation, both by sea and land.

Vice Admiral Sir Montague E. Browning headed the British delegation, and he requested as many destroyers as possible, — at least six. “Even one,” he said, “would be better than nothing.”

He urged the moral effect of the United States flag flying in cooperation with the British Jack in the War Zone.

General Joffre pleaded for at least one division of troops at the earliest possible moment, and he placed the limit of our contribution to the cause at about 400,000 men.

The point emphasized by these special envoys was that however insignificant in point of numbers or equipment the first reinforcements ashore and afloat might be, they would show unmistakably to the Central Powers that the intention of the United States was to use her armed forces to the limit with the Allies. How amazed they would have been could they have foreseen the extent of America’s answer.

The Destroyer Force Was Ready

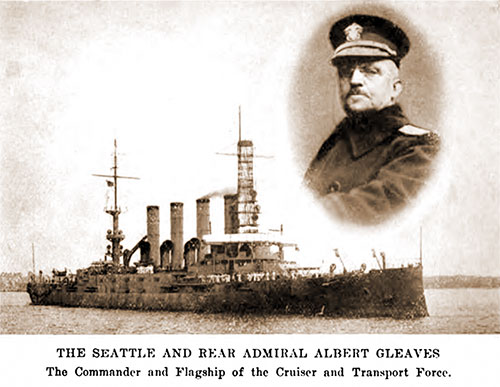

The USS Seattle and Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves. The Commander and Flagship of the Cruiser and Transport Force. Our Navy at War, 1922. GGA Image ID # 1803ab189c

When the order came for the destroyers to go abroad, they were ready; and they might have sailed direct from Hampton Roads as soon as fueled and provisioned for the cross Atlantic voyage, had the Department considered such quick dispatch necessary.

When the United States entered the war, I was flying my flag in the armored cruiser Seattle and had been in command of the destroyer force since November 1915.

As Germany developed her submarine campaign, it became evident that should war come there would be an immediate demand for destroyers. During the winter months of 1916-17, therefore, in addition to the usual exercises with guns and torpedoes, the destroyers carried out a series of tactical and strategical evolutions, especially designed to train the personnel and test material under simulated war conditions.

In this way a sound doctrine based on experience was developed which brought the destroyers to a high pitch of fighting efficiency. Deficiencies in material were discovered, and on February 21, 1917, I addressed a letter on this subject to the Commander-in-Chief. In retrospect the following excerpts are of interest:

- The Commander, Destroyer Force, climates that the present situation demands that all destroyers be put in thorough readiness immediately for service on the high seas.

- When war is declared there will doubtless be an immediate demand for destroyers and cruisers, which will probably be met by releasing destroyers from duty with the Fleet, and by immediately placing in full commission all destroyers and cruisers.

- It is recommended that all destroyers not materially ready be immediately sent to Navy Yards for repairs, and that their duties of preserving neutrality, etc., be taken over by destroyers now ready for distant service, keeping with the fleet only such destroyers as are absolutely necessary for its safety.

- It is recommended that all destroyers of Flotillas One and Two be sent to Navy Yards to fit out for full commission and be put in thorough readiness for distant service.

- It is recommended that all complements of all destroyers be filled.

- It is further recommended that no officer who has not had experience on a destroyer, and who is below the rank of Lieutenant be ordered to command any destroyer, and that such orders as may be necessary to put this recommendation into effect be immediately promulgated.

The prompt action taken by the Navy Department on these recommendations made possible Commander Taussig’s famous report to the British Admiral at Queenstown, "We are ready now.”

The Lack of Transports

Due to lack of transports, it was not such an easy matter, however, to get the Army across. The War Department had agreed to send about 10,000 troops, and the Navy Department promised to convoy them. No time was lost in chartering available vessels and converting them into troop transports; at the same time the Navy Department began to assemble at New York the ships which were to act as escorts.

Although these preparations were conducted with the greatest secrecy, the outfitting was done at New York, mainly at Hoboken, and the German Intelligence Department would not necessarily have possessed super-knowledge to have had fairly accurate information of what we were doing. There can be no doubt that they were informed of the sailing, as events afterward proved.

The First Expedition to France

On 23rd of May 1917, I was informed in Washington that I had been selected to command the first expedition to France. I returned to New York at once, and personally inspected the ships which the War Department had taken over; after consulting with the Army Quartermaster in charge of the conversions we notified our respective departments that the expedition would be ready to sail on June 14th, and accordingly at daylight on that date in an exceptionally thick fog, the entire force got under way from North River and the Lower Bay, and stood out to sea in prearranged order.

It was a memorable occasion when the transports backed out into the river from their piers, and the cruisers, yachts, and destroyers weighed anchor. Only the most skillful handling of the ships by their captains could have prevented collision at the start, but the necessity of the occasion justified all risks.

The force was divided into four groups, which were scheduled to sail from Ambrose Channel Light vessel at intervals of two hours; the first group was the fastest; the fourth group the slowest.

The sailing interval was thus arranged to avoid congestion at the port of arrival. The schedule was adhered to, except that the fourth group was delayed several hours by the Navy Department to receive belated mail, a few special packages and some additional stores.

The group formation was adopted, as obviously it would have been unwise to have sent the entire force through the submarine zone en masse, and the different speeds of the groups separated them more widely every hour.

The entire number of vessels in the expedition was thirty-seven, composed of cruisers, destroyers, converted yachts and transports. The total number of troops in the first division was 15,032, under command of Major General Sibert, whose headquarters ship was the steamer Tenedores.

The cruisers were Seattle (flagship), Charleston, Birmingham and St. Louis. The destroyers were Wilkes, Terry, Roe, Fanning, Burrows, Lamson, Allen, McCall, Preston, Shaw, Ammen, Flusser and Parker. The converted yachts were Corsair and Aphrodite. The transports were Tenadores, Saratoga, Havana, Pastores, Momus, Lenape, Antilles, Mallory, Finland, San Jacinto, Henderson, Hancock, DeKalb, Dakotan, ^Montanan, Edward Luckenbach and El Occidente.

The Problems of Transportation

In fitting out this expedition the Navy entered a new field. It is safe to say that in our peace time studies of the conduct of war, we had directed the larger part of our consideration to the military and naval requirements of situations presupposing that any possible enemy would bring his army to us.

I can recall no major problem of the War College Course that contemplated the transportation of an American Army to Europe.

Therefore, when suddenly confronted with the proposition we found elements for new thought. The organization, supply, and sanitation of types of ships unfamiliar to the Navy for the transportation of troops overseas presented serious and complex problems, which demanded speedy solution.

It was fully appreciated that dissatisfaction among the troops, arising from lack of medical attention, poor food, or uncomfortable living quarters might damage their morale, and it was paramount to land the soldiers fit and in good spirits.

Protection, Escort, and Routing

Naturally, the question of protection raised greatest concern. This, of course, involved the routing of the ships across the ocean, as well as their material protection.

These ships were to be crowded to the utmost and a disaster to even one would have, as someone afterward remarked, as disheartening an effect upon the nation and the Allies as the first Bull Run.

In the first place, life-saving equipment was provided to take care of the entire ship’s company. Stringent orders were issued that no lights were to be shown at night—every effort was made to prevent the ships “torching”; smoking on deck was absolutely forbidden.

The gun crews slept at the battery and ate their meals there. Numerous lookouts were stationed below and aloft.

Generally speaking, the formation of each group was to place the transports in the center, while the escorting ships were disposed on the flanks in such a way as to provide all around protection.

The Maumee, oil tanker, was sent on several days ahead of the expedition, with orders to maintain a certain position on the route for the purpose of refueling the destroyers at sea, a maneuver involving special gear and seamanship, which had been successfully developed in the destroyer force only a few months before.

Without the ability to oil these destroyers at sea the expedition would have been greatly delayed, because all except the newest of them would have had to be towed.

First Submarine Attacks

The route of the expedition lay well north of the Azores, as it was known at that time the Germans were using those islands as a submarine base.

The so-called submarine zone extended to 170 west longitude, but the latest reports received from the Navy Department before sailing showed sinkings as far west as 30 degrees.

I thought it probable that we would encounter submarines any time after passing the 25th meridian, and all the ships were so informed by the secret routing instructions and sailing orders which I issued prior to our departure.

The voyage was uneventful save for a night attack against the first group by submarines on the 22nd of June 1917, in latitude 48°00'00" north, longitude 25°50'00" west.

The following day the first group was met by a destroyer division from Queenstown and later by two French sloops which had been sent out to meet us, and to act as escort to Quiberon Roads. The next morning we arrived off St. Nazaire.

The second group was also attacked by a submarine when about 150 miles off the French coast. Commander Neill, who attacked the submarine, was subsequently decorated by the British government for this exploit.

The third and fourth groups arrived on schedule time, and on June 26th the last vessels were safely anchored in the St. Nazaire Roads.

This was only the beginning, but the way had been pointed out, and from this modest start was rapidly developed the greatest transport fleet in history.

Subsequent voyages were of greater magnitude, but different only in details. Neither winter gales, nor heavy seas, nor the spread of submarines to the very gates of our harbors ever delayed the sailing of a transport by an hour.

While we have cause for satisfaction in this troop transportation achievement there is an important lesson for the future which should give us pause. It is this: A nation, situated as is the United States, must have a flourishing merchant marine if she is to be self-reliant.

Due to the failure of the United States to develop a deep-sea merchant marine we were forced to depend upon foreign bottoms to carry a little over half of our Army abroad. Moreover, a large part of the United States naval transport fleet was made up of seized German ships. The following figures illustrate this point.

Over 1,100 Transports with Troops

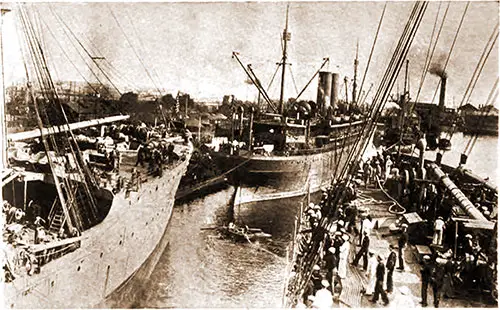

Congested Condition of St. Nazaire Harbor, the Landing Place of the First Expedition. A History of the Transport Service, 1921. GGA Image ID # 18a51915c4

There were, in all, 1,142 troop-laden transports that sailed from these shores for Europe, and they carried a total of 2,079,880 soldiers. Forty-six and one-quarter percent, were carried in United States ships, and all but 2 1/2 percent, of these sailed in United States naval transports.

Lacking a large merchant marine, our government was compelled to contract with foreign governments for the transportation of 5 3/4 percent, of this Army in foreign bottoms.

At great expense, a total of 208 foreign ships were employed: 196 British, eight French, two Italian, one Norwegian, one Portuguese and one Brazilian. Forty-eight and one-quarter percent, of the United States overseas Army was transported in British ships, 3 percent, in British leased Italian ships and 2)4 percent, in French, Italian and other foreign ships.

In the month of July, 1918, during which more of our soldiers were transported in foreign ships than in any other month during the war, British ships carried 175,526, or 56 1/2 per cent, of the month’s total of 311,359.

This was the greatest number transported in any one month under the British flag. In the same month of July 1918, 11,502, or 3/4 percent, of the total, sailed in British-leased Italian ships; 11,866, or 4 percent, of the total, in French, Italian and other foreign ships; and the remainder, 112,465, or 36 percent, of the total, sailed in United States ships.

This was the smallest percentage carried in any one month under the United States flag.

Troopships Chiefly Under American Escort

In the matter of providing escorts for these transports, however, the figures are more satisfactory, although here again it is to be remembered that the naval power of Great Britain was concentrated in the North Sea while that of France was held for the most part in the Mediterranean.

All the troops carried in United States ships were escorted by United States men-of-war; that is, cruisers, destroyers, converted yachts, and other anti-submarine craft. Also, for the most part, the troops carried in British, French and Italian ships were given safe conduct through the danger zones by United States destroyers.

In connection with this work it should be mentioned that, in addition to the twenty-four United States cruisers assigned for ocean escort duty, there were with my Force a squadron of six French cruisers to assist in this work and they did fine and useful service.

Roughly, 82 3/4 percent, of the maximum strength of the naval escorts provided incident to the transportation of United States troops across the Atlantic was supplied by the United States Navy, 14 1/8 percent, by the British Navy, and 3 1/8 percent, by the French Navy.

The Array organized and developed an efficient system for loading and unloading the ships at the terminal ports. The Navy transported the troops and safeguarded them en route.

In the transportation of troops and supplies to Europe the nation owes much to the officers and men of the merchant marine; they were comparatively few in number, but their service was invaluable, and without their assistance the Navy Department would have been embarrassed to meet the expansion of the Navy.

It is a matter of profound personal satisfaction to have had the opportunity of working with these skillful sailors, and of observing them at close range. They were anxious and eager at all times to acquire naval customs, and with a willing and patriotic spirit they broke away from a life-long training on parallel but dissimilar lines to learn new customs and to attain a new point of view.

They were zealous and efficient, and they served with credit and distinction. Our new-born merchant marine has a prosperous future under their guidance.

The German boast that we could never land an army in France was as empty as was their psychology in general. In our Revolution Washington acknowledged that it was the French fleet under De Grasse in the Chesapeake which made possible his victorious peace.

Now, one and one-half centuries later, the American Navy has been privileged to do a like service for Marshal Foch and France.

When the armistice was signed the return of the troops was ordered, and ever since they have been returning in constantly increasing numbers at a rate which far exceeds their outgoing.

In the month of June 1919, our United States naval transports returned 314,167 fighting men in 115 sailings. In addition, in this month, foreign ships returned 26,825.

If this can be taken as an indication of the future development of our merchant marine, it is encouraging. In seven months more than one million men were landed in the United States, and the Leviathan—the biggest of all the transports—carries almost as many people on each voyage as were carried in all the transports of the first expedition.

Zigzagging, lookouts, darkened ships have passed into history. The seas are once more free to those who pass on their lawful occasions.

Vice-Admiral Albert Gleaver, USN, "Moving Our Troops Overseas: The Office Figures of Uncle Sam's Prodigious Effort to Increase the Allies' Manpower," in Harper's Pictorial Library of the World War in Twelve Volumes Profusely Illustrated: Volume IV: The War on the Sea: Battles, Sea Raids, and Submarine Campaigns, New York-London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1920, pp. 157-165.