Making a Soldier Out of Johnnie - 1918

Edward Hungerford's article about life in a World War 1 Cantonment appeared in the February 1918 issue of Everybody's Magazine. It gave people a taste of what a new soldier could expect during his training.

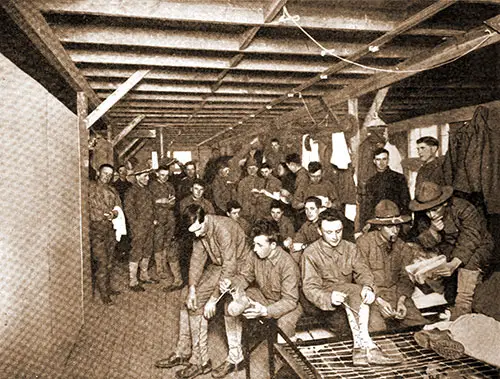

They Have Taken the Slouch Out of His Shoulders; He Stands Erect for The First Time in His Life. Photograph Copyrighted by Brown Brothers. Everybody's Magazine, February 1918. GGA Image ID # 1a1a2a5cef

They are making a soldier out of Johnnie. They have taken the slouch out of his shoulders and the looseness out of his entire posture, and he stands erect for the first time in his life.

They have put him in uniform and given him a gun. He has had the manual of arms and training in extensive warfare such as was not even in the dreams of West Point three years ago.

They have done other things to John; not so visible at first glance, but quickly discernible when you come to talk with him. They are things that are to stay with him all his days. When he gets home again, he will not be quite as flippant in talking about the "old man" or the "old lady."

A Maker of Americans

The army teaches respect; it is part of discipline. And John has been taught genuine discipline. There are, of course, several good military schools in the land which teach this thing.

If there had been no war, the cantonments would have been worth their cost—in effort and money—for this thing alone. But their influence has been negligible when comparing it with our enormous population.

Few boys have been able to enjoy their advantages. But the cantonments are reaching nearly three-quarters of a million young men already; are making them not merely soldiers, but real men—Americans, clear-thinking, and alert in mind and body.

The best argument that we have had for universal training is to be found in these sixteen cantonments. They have now been in existence long enough for even the most casual observer to appreciate not merely their worth to the boys who have been fortunate enough to be admitted to them, but the possibility of such as these to future generations of American boys—war or no war.

A boy may indeed be genuinely envious of the young men who in 1917 were conscripted for our National Army. It is to be hoped that the lesson of all this will not be upon the boys alone; that some of it will filter through the minds of those estimable gentlemen who make our laws and so diligently guard us against ourselves.

Four days after Johnnie arrived at the cantonment, they had him in khaki. And hardly had he passed his physical examination before they were at him with the setting-up drills and preliminary physical exercises.

Upon the heels of these came the simple military formations—the men being "told off" into squads of from ten to twenty each and placed in charge of a first sergeant —in army parlance a "top-sergeant"— a man who but a few weeks before was probably but a raw recruit himself.

But such is the simplicity and thoroughness of present-day methods of military education that almost any keen-witted, able-bodied young man can be whipped from rawness into a presentable soldier within a period to be measured by weeks and by days rather than by months.

And there has been no shortage of either keen wits or able bodies in the young men who have presented themselves at the sixteen cantonments of the National Army.

A Unique Army

In some directions and several times, there has been a tendency to decry this National Army. An unfair criticism, usually arising from jealousy; and most unjust.

My answer to it comes from the most distinguished of the younger officers of the Regular Army—a West-Pointer whose service record began in the Spanish War and has led him steadily upward ever since.

"Like many Regular Army men, I was rather strongly prejudiced against any other soldier organization," said he. the other day. "I felt that we possessed, in the old Regular Army, morale, a distinction, man for man, that no other organization, civil or military, here or abroad, might ever attain.

Now, I am glad to say that I was wrong—entirely wrong. I have been with the National Army for four weeks now, and I am convinced that this body of men which we upraised in 1917 is going to prove itself the most distinguished fighting organization in the whole history of this nation, if not indeed in the entire history of military science."

There Is a Short Rest in The Middle of The Morning When There Is No Work, But All Play, Until Grub-Time. Photograph Copyrighted by Brown Brothers. Everybody's Magazine, February 1918. GGA Image ID # 1a1a39252e

Developing Initiative

He has had the opportunity to observe.

A few months ago, he was brought home from a military station in the Far East and told to organize the course of military instruction at one of the prominent National Army cantonments.

"How do you wish me to do it?" he inquired.

"You will have to work it out yourself," his commanding officer told him and walked away.

"And yet," says this West-Pointer, "there are men who persist in saying that the Army offers no chance for the initiative."

He turned to the organization there at his division headquarters. He had authority, and having authority, he chose assistants—when and where he chose.

And when these younger officers asked him for detailed instructions, he smiled and repeated the instructions he had received from his commanding officer.

Officers only told them the results that they must attain. The rest they would have to work out for themselves.

The West Pointer first had a set of trenches dug—three deep and some three or four hundred yards in length, with connecting trenches and gun emplacements, all just like the trenches "over there."

Then he took the conscript men—already showing the sound effects of drill and discipline—and from them chose as grenadiers the tallest and the strongest.

The men have chosen to throw the hand-grenades stand at a distance of approximately sixty yards and throw into baskets whose open tops are barely four feet square to improve the sureness of their aim. This is not an easy trick, particularly for a novice.

If you do not believe it, get a bowling ball and try it yourself; for a hand-grenade is not unlike an average bowling ball in size or weight. And it is thrown in much the same way.

The grenadiers generally try at first to throw it as they would a baseball; such is the cost of our devotion to our national game.

Then, after they have convinced themselves of the impossibility of that method, they fall into the right way and do better than hitting the baskets once in a hundred shots. Steadily they improve, and when they are graduated, their batting average will credit a major league.

Then they are graduated into a rifle grenade which slips upon the barrel of one of the new Enfields or the older Krags and, of course, carries to and explodes at a much greater distance than sixty yards.

The first time I tackled a hand-grenade, I blew myself to pieces—that is, the instructor said that I did. Five seconds elapse before the time you release the trigger and the exact moment that the grenade explodes into a thousand pieces.

I stood looking at the grenade seven seconds after I had released the trigger—and was two seconds in eternity. Only the grenade was not a real one. It was stuffed with sawdust instead of gunpowder.

All the boys get the sawdust ones at first. They will have to be very proficient before they are entrusted with anything more deadly.

A Grim Grind

The daily grind is challenging for John, you say, tremendously hard. Of course, it is. War is no picnic. War is a complicated, serious business, and training for it is bound to be hard, serious work. For instance, consider the lethal- house, that sinister-looking structure of yellow pine boards that have become a part of the cantonments. Its looks do not belie it.

For it is within that tightly sealed place that John must undergo the distinctly unpleasant and dangerous business of chlorine gas for the first time. Only it is not going to be hazardous or even particularly unpleasant if he keeps his gas mask tightly fastened upon his head and shoulders.

And the psychology of the experience is going to be that when he gets over there, and a yellow flood of chlorin gas comes pouring across No Man's Land, he is not going to be sick at his stomach and ready to turn tail. Still, he will realize that he is invulnerable to the poison in his modern mask and will keep straight ahead through it.

These deviltries of the Germans are not going to come to him on the battlefields as complete and terrible surprises. He is being schooled against them, taught how most effectively to resist them. And that is why they are going to "play" with liquid fire at each cantonment.

And for that thing alone, every American mother who has a son in any of the cantonments ought to thank God that her son is fighting for a nation that does not send its boys into battle afraid and unprepared.

With Present-Day Methods, Almost Any Keen-Witted, Able-Bodied Young Man Can Be Whipped from Rawness into A Presentable Soldier in Weeks and Days Rather Than Months. Photograph Copyrighted by Brown Brothers. Everybody's Magazine, February 1918. GGA Image ID # 1a1a6a2a67

Getting Ready

His, after all, is the big end of the camp work. We soon shall see the lighter side of its activities. But let its more serious; by far, its most essential, side come first.

And before we are done, let us see a squad, another squad, a dozen squads come running down a company street—each man in his gymnasium running-togs, knee-breeches, and sleeveless jerseys.

"Going to have an inter-company meet," you venture, "or perhaps an inter-regimental one."

You are right—and you are wrong. It is athletic work—and much more. It is part and parcel of the making of the soldier. A little later, he will have to run with his fellows; no longer dressed in "gym togs," but in full uniform—rifle and dirk and field equipment of every sort to boot.

He will have to run, and then he will have to climb into the seven-foot-deep trenches —in double-quick time. There is nothing easy about this training. Or soft. But it is thorough. And that, of itself, should be a cause for thankfulness.

And finally, the instruction in hand-to-hand conflict. Down a company street at Yaphank, I saw a row of gibbets—a boyhood knowledge of Robert Louis Stevenson had taught me they were gibbets.

And from each gibbet hung a man—a man of straw, a crude effigy which men fought with bayonets. And later, actual hand-to-hand conflict—wrestling and boxing, with a knowledge that the Marquis of Queensbury is quite an unknown gentleman to Hans. Hans only knows Nietzsche.

And the disciples of Nietzsche have taught him that the fair—the honorable way, if you please— to meet an adversary in personal encounter is to murder him in cold blood, by foul means if necessary.

Sometimes the instruction grows more technical.

A company, battalion, or even a whole regiment, may be ordered to the trenches at dusk to gain a little practical experience in night attack or defense.

Heavy marching order is the instruction is given, which means arms and all accouterments—with the single exception of ammunition. And every ninth man is told off and given a lantern.

Conversation is forbidden. Whistling or singing is a high military offense. And even when the long files have dropped softly down into the communicating trenches and the shoes of some unwitting private have scraped against stones left in the bottom of the ditch, there are sure to be sharp words from one of the young Plattsburg officers who takes the whole business very seriously indeed.

He is right. For over there away, a few hundred yards are the [Germans], whose ears are never asleep; and even if the [Germans] are not there on this night of rehearsal, the real first-night is coming when a single unnecessary noise in the trench-system may mean attack and excessive loss of life.

Some men go into the third line trenches, others into the reserves, and others—more favored than their fellows—into the firing-line trenches. After that, the game is one of silence and of waiting.

"Patience" is hard to be compared to it. And the first time one of the young conscripts gets restless and pops his inquisitive head up over the trench-edge, there is a telephone message, the quick thrust of a high-powered searchlight upon his dazed face, while a lieutenant slips up to him and tells him to withdraw.

He is dead, theoretically. But that is not the worst. He has exposed his fellows to sudden attack. War is a business, which is tremendously dependent upon the individual human factor in the last analysis.

In Dead Earnest

I have a friend—a young six-foot officer and powerful ask a horse—at one of the cantonments in the far South who has a way of showing this need for individual responsibility.

His practice is to skirmish around the camp late at night and approach the sentries, giving careless, indifferent, casually friendly replies to their challenges.

In his happy-go-lucky backcountry fashion, the sentry feels that the stranger is not merely a friend, but. of the cantonment. Then—two hundred pounds of brawn and muscle land upon him; he feels an awful blow in the pit of the stomach; his gun is taken away from him, and he finds himself sprawling on the ground. As soon as he can get his breath, he looks at his attacker and begins:

"What the

"Exactly so," interrupts the officer, "only if this had been No Mans - Land and I a German scout you would have been completely dead by this time."

They are taking few chances in the training of our great new Army.

Sometimes along with about dawn, the regiment is dismissed and goes to breakfast and coffee—and steaming- hot coffee at the various barracks.

Only this morning, instead of turning into the stringent morning routine of drill and training, it turns into the neat iron cots in the dormitories, joints tired and bones aching, but in a few hours to be vastly better, mentally and physically, for the experience.

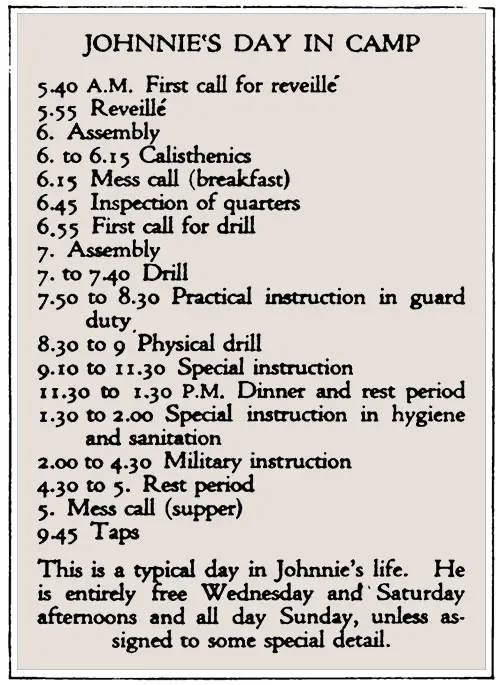

On ordinary days the routine is barely begun at breakfast, which is served at the distinctly unfashionable hour, a quarter after six. Twenty minutes before was reveille—the time-honored "They won't get up, they won't get up, they won't get up in the morning" was sounded, and files of sleepy and somewhat disheveled men were forming in the dark of every company street.

Those luxuries can come later in the day—when there are short respites from the camp routine. They no longer have a place in an early morning schedule. The fastidious fellow who has been used to his early morning bath and shave has had to change his habits.

Nor in a later morning schedule either, for that matter, For breakfast is hardly out of the way before the drill begins; special training of every sort— a short rest in the middle of the morning just like the old-fashioned school recess when strict orders provide that there shall be no work but all play, and continues until noon.

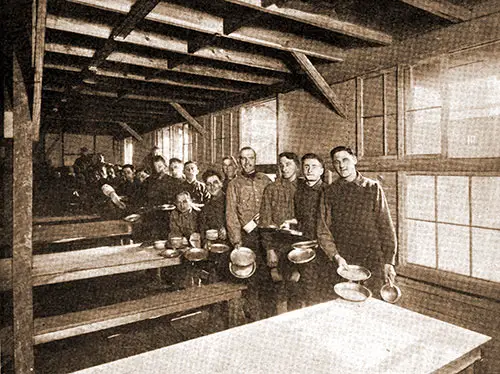

Grub-time again. The men fall into line in the extensive barracks mess-halls, their mess-pans in hand, a hungry, anticipatory, healthy lot of human animals waiting to be fed.

A Typical Soldier's Schedule During Training in a Camp of the Regular Army. His day begins at 05:40 and ends with Taps at 21:45. Everybody's Magazine, February 1918. GGA Image ID # 1a1a6d6bdf

A Well-Fed Army

And such food! I never expected to eat better than I had at the cantonments this last autumn or more of it. The very generosity of the cooks has made a particular problem of itself.

In their anxiety to see that no man was underfed, they have overdone it. And the men, themselves, have not cared. So now Camp Devens has a rule which gives a second helping to any man who asks for it.

Mr. Hoover himself could hardly have conceived a better plan. Only he must eat up that second helping. If he does not, his mess-pan is tagged when he turns it in at the end of the meals, and the food he left over at the one meal—sheer wasting if you please—becomes the first course of the ensuing one.

Work through the afternoon, supper at the very unfashionable but extremely popular hour of five, and then freedom until taps, promptly at nine forty-five o'clock in the evening.

These are old-fashioned hours and sensible. And there is not the slightest doubt in my mind that much of the excellent health records of the cantonments are due to them, as well as to the open-air exercise and the abundance of simple, well-cooked food.

At Grub-Time, A Hungry, Expectant, Healthy Lot of Human Animals Fall into Line, Mess -Pans in Hand, Waiting to Be Fed. Photograph Copyrighted by Brown Brothers. Everybody's Magazine, February 1918. GGA Image ID # 1a1afad629

The food is good, and the men thrive upon it, despite the temptations of the post-exchanges—in other days known as canteens—with their allurements of soft drinks and candies and fancy cookies upon their shelves.

The quantity of this stuff, which is consulted, even on an average day, is staggering to the imagination. Johnnie has an appetite hardly to be compensated by three meals a day. Likewise, our John has thirty-two extremely sweet teeth.

You do not express surprise and more when you are told that in the eighteen post-exchanges at one cantonment, a business of more than three hundred thousand dollars a month is done; four great motor trucks give all their time to bringing supplies from the railroad and the express stations.

And more than one thousand pints of milk are sold daily over the counters to the boys in one store in one cantonment. Multiply that thirty-two by forty thousand, and you begin to see the enormous candy-buying and gum-chewing power of a single cantonment.

And smokes—oh, John! A single average camp sells five million cigarettes a week; all of them together one hundred million cigarettes in seven days—for there is no Sunday-closing law to apply to the cantonment stores.

It is recognized as a sort of inherent privilege. It does much to make for the real democracy of our Army. Yet, even the most radical of the anti-cigarette leagues have not seen fit to oppose the soldier's rational desire for a smoke.

John's Recreation

The athletic training of the boys at the cantonment falls partly under the Commission on Training Camp Activities, under the direct interest of Dr. Joseph E. Baycroft, of Princeton University, who has given a lifetime of study to this work.

And this is as good a time as any other to study the important and interesting work of the Commission on Training Camp Activities, which is a governmental function under the allied control of the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy.

It represents one of the many steps now being taken in Washington to centralize the activities arising from the conduct of the war rather than to spread both further and thinner.

An article in a recent issue of Everybody's told in much detail of the elaborate plans and work of the Young Men's Christian Association with the men of both our Army and Navy.

I cannot, myself, pay too high a compliment to that work. It isn't easy, but it is done thoroughly by peculiarly experienced men and qualified for it.

I found a young man in the gray uniform of the Y. M. C. A. sweeping out one of the green huts, which in other days was the pastor of a splendid congregation in one of the intelligent suburbs of Boston.

He was donating his services—magnificently and generously. And he was but one of many.

For many years, the Y. M. C. A. has studied the social and religious needs of the soldier and the sailor. Its houses for the sailors at Brooklyn and Norfolk and other places are wonderfully elaborate and well-fitted.

It won the hearts of the men who have mobilized two years ago upon the Mexican border. But unfortunately, it is, to a degree, handicapped by its name.

Organized as a benevolent organization for young men of the Protestant evangelical churches, it loses force with the young men of other faiths. And the most immediate needs of the young men of our cantonments are moral and physical rather than distinctly religious.

The first of these points was overcome at the beginning of the organization of our new Army by the admission at the cantonments of the headquarters buildings of men's associations of other faiths.

In the fieldwork, that organization knows neither race nor creed. The Knights of Columbus have represented the Roman Catholics and the Y. M. H. A. the Jews, both very creditably.

And it is to the further credit of the Y. M. C. A. that in several instances where these other organizations were not able to complete and open their headquarters buildings as promptly as had been hoped, they were invited to use and did use the facilities of the Y. M. C. A.

The Problem of Visitors

Neither does the Y. W. C. A. It desired to erect hostess houses, where the wives and mothers and sweethearts could meet the boys during the hours when they were free from drill and duty.

The first of these houses was erected two years ago at the earliest of the officers' training camps at Plattsburg. The commandant located there was rather timid about having it built upon the Government reservation. Finally, he gave his consent.

But this year, when it was proposed that a hostess house be built near the cantonment to which he was assigned, he insisted that it be put up within the camp's boundaries, where he could guard and protect it.

There is a deal of variance among the Army men as to how the women relatives of the soldiers should be permitted to visit them at the cantonments.

"I like to have the women folks come," said one of the commanders to me. "It keeps the boys contented, and it lets their families see and know the comfortable conditions which surround them here."

That is an excellent view of the problem. Other army veterans shake their heads somewhat dubiously at it. They have viewed with a degree of consternation the rush of wives of the young officers to take quarters in the towns adjacent to the cantonments.

In some large cities such as Atlanta, Louisville, Columbus, or Little Rock, this has made little if any upset to living conditions. It has become a problem in smaller communities, like Rockford, Battle Creek, Chillicothe, and Petersburg.

And in such cantonments as Yaphank, Wrightstown, Annapolis Junction, and Ayer, it is a calamity. I know of one town adjacent to a cantonment, which is endeavoring to manufacture Government munitions and partially failing because of the inability to house the workmen that should be employed in its shops.

Yet the young officers' wives have not hesitated to come in and fill the available living accommodations of the town. Because of this condition, Secretary Baker recently issued a request that the families of both officers and men refrain as far as possible from taking living accommodations close to the cantonments.

Yet in one particular case—Camp Sherman at Chillicothe, Ohio—the Government has purchased a plot of ground close to the camp and is building both a club and residences, facilities which the town was either unwilling or unable to provide.

The Camp and the Family

A single instance at Rockford, Illinois, shows this congestion problem. The cantonment there—named Camp Grant after the great soldier who came out of the tiny nearby city of Galena has a social distinction, which few of its fellows have attained. Most of its men come from that particularly virile and American of cities—Chicago.

And Chicago has taken Camp Grant to its warm heart. The houses of Rockford have been leased, some of them at well- nigh fabulous prices, by the elect of the city by Lake Michigan.

One prominent woman, whose husband is an officer of the cantonment, found it quite impossible to rent a house or even an entire apartment, so she hired the billiard room of an apartment-house— a vast apartment.

A decorator from Marshall Field s came out and utilized great screens upon which blue - and - white striped denim was stretched, making the billiard room into six separate rooms.

They were furnished in Army style but with exquisite taste. And the Chicago woman now possesses an apartment suite at the cantonment, which excites the envy and admiration of everyone who sees it.

The hostess houses of the V. W. C. A. are valuable because they solve the cantonment's rather embarrassing social problem. For no matter how the Government may seek to discourage the families of the new soldiers from taking residence nearby, it is going to encourage their frequently coming as visitors.

And the hostess houses furnish the places for making appointments. Women are not allowed to wander at will, unescorted about the cantonments. And a woman found breaking this rule will be directed, politely but firmly, to the nearest hostess house. One may send a message to the soldier who is wanted.

All these activities—and many more —are finally being concentrated under the Commission on Training Camp Activities, of which Raymond B. Fosdick, of New York, is the highly efficient chairman.

They are becoming arms of the parent organization, which probably will constantly assume more detail. It is studying the entire problem with great care and guided by the best expert advice in the land.

Educating John

The Commission divides training camp activities into two great groups—those inside the camps and those without. The things that we have just seen are of the first group.

Education is a more significant problem than it might seem at first glimpse and is worth a moment's attention. Physical instruction and education are also of it. Physical schooling is even as differentiated from the drill we have seen already.

When I was in Louisville in September, I noticed placards up and down the streets of that lovely town, asking the citizens to contribute one dollar each for the teaching of reading and writing to untutored lads out at Camp Zachary Taylor.

There are thirty thousand illiterates among the young men of Kentucky. Many of them are in cantonments and are making good soldiers. But few of them have ever been away from home before; indeed, few had ever boarded a railroad train until they started for the Zachary Taylor.

These boys are willing and anxious to write home, but it has been beyond their knowledge. Before the cantonment training is over, they will be able to read and write with a fair degree of a facility, which is a by-product of the National Army training that is hard to ignore.

Fosdick had rather ambitious plans for this educational work when he became Chairman of the Commission on Training Camp Activities. He went so far as to see vocational training become part of it.

But the extreme time pressure placed upon the cantonments because of the growing necessity for troops in France has made it impossible to put these more elaborate plans into effect—for the immediate time, at least* But the teaching of the more specific subjects, such as we have just seen, has been a tremendous success.

And so has the teaching of French; it is safe to say that never again will the French language be the accomplishment of the few in America—for the war has done wonders in establishing its popularity over here.

Amusing John

One thing more, before we leave the work of safeguarding Johnnie while he is within the boundaries of the cantonment—amusements. A most unusual and energetic member of the Fosdick commission is Marc Klaw, the veteran theatrical manager of New York City. Under his direction, a vast theatre is being built at each cantonment.

There are no balconies or galleries, but each of these theatres will seat upwards of three thousand men. Their stage facilities and equipment will be metropolitan; indeed, they will have to be because urban successes of every sort are to appear upon them—in one-week stands.

And the prices are to be ten, fifteen, and twenty-five cents a seat, with no speculators on the street outside or hidden in convenient nearby cigar stores.

While these tickets are all to be reserved, an ingenious method of paying for them has been adopted. "Smileage books," modeled closely upon the mileage books of the railroads, but containing coupons valued at five cents each in exchange for seat tickets for the Liberty Theatres, have been prepared and are being offered for sale at many drug stores and cigar factories in the cities and the larger towns across the country.

In the beginning, it was planned to reserve four hundred seats in the body of the house for the officers, and thereby hangs a story—which had told me about the other day by a British officer of high rank—to illustrate the hate for the Hun which had been instilled into the hearts of the men of the English Army. No true Britisher ever speaks of Germans; they are always the Huns these days.

He made the caste of the British Army quite clear to me. An officer back in London on leave and seeking out an inexpensive restaurant makes sure that there are no Tommies in there before he enters; they would be embarrassed; and so, would he. At least, that is the English way of looking at it.

On the day that this officer took the top of a' bus ambling along Whitehall, he did it with many misgivings. Still, cabs are none too plentiful in London these days, and there was no one at the time and place he wished to leave. So, he rode that bus.

And sure enough, upon the crossbench in front of him were two enlisted men. But it was entirely too late for him to turn back.

"Bless me, it's a wonder the officer might not have taken a taxi; and not a-riding on a bus with us as we get a shilling a month," said the Tommies to one another.

At least, the officer imagined that they were saying to one another as they talked together with a tremendous earnestness. But the officer was more interested in the passenger who rode in front of them— unquestionably a German or a man of German lineage—fair-haired, pink-skinned, with his very pink cars sticking straight out from the sides of his head.

Suddenly one of the Tommies turned, saluted, and addressed the officer. He nodded toward the man in front.

"Do you think he's a Hun, sir?'* he asked.

"I don't think so," said the officer.

"That's good, sir," was the reply, "otherwise, we should have had to dump him into the street." He made an expressive gesture with his thumb to illustrate the process of dumping. And there was not the slightest question that they would have done so and never have looked back or cared to see whether he went under the wheels of the first passing lorry or motor.

A Democratic Army

The English officer told me this story to show the way hatred of the enemy has been implanted in the breasts of all their enlisted men, but somehow that caste idea could not get out of my head; of officers and men studiously avoiding one another in restaurants and cars and half a hundred other places.

The idea of the seats set aside in the cantonment theatre is quite in line with the upbuilding of a caste in our American Army. But this war seems to be breaking down the caste of our Regular Army of peace times rather than creating a greater one as the Army grows.

Our ideals along these lines seem to be far more of the French army than of the British, where caste is an outgrowth of a long-established social system, which is not capable, even in war times, of quick or easy change.

Major-General Henry W. Hodges is at the head of Camp Devens, at Ayer, Massachusetts.

Along with the fall, one of the big tents of the Redpath Chautauqua circuit pitched itself in the heart of the cantonment. Hodges went to see the show. The attendant at the gate quickly recognized him.

"There's a box reserved for you, sir," he said.

"Thank you," replied the commanding general, "but I would prefer to sit with the boys in the body of the house."

The Square Deal

Talk about democracy in the Army.

A Jewish radical from New York's East Side—a writer and an orator of no small merit—was caught in the draft. He protested vigorously but to no avail. He said that he would not fight under any circumstances.

And when he arrived at the big cantonment down at Yaphank, on Long Island, he refused to drill and was so noisy and persistent in the refusals that he was placed under arrest.

News of his case drifted to division headquarters up atop of the hill. And Major-General Franklin Bell, commanding the division, directed that the prisoner be brought before him.

The two were closeted for more than three-quarters of an hour. At that time, General Bell argued as he had never argued before. He took the entire human course of trying to convince the pacifist that he was wrong, that the hour had come for America to strike and to strike hard, And succeeded in his task.

"I will be loyal/' said the Jew from the East Side of New York, "and fight and drill to the best of my ability."

But as he came out from the inner office, he hesitated on the threshold.

"I suppose it would not be of any use for me to ask a favor of you—not now at any rate."

"It would depend upon the favor," said General Bell.

The former pacifist straightened himself upon his feet.

"This is the twenty-fifth of September," he said, slowly, "and a great holiday among my people—the feast of Yom Kippur. Never have I missed it. But this year, I am a prisoner."

"A prisoner bound by honor," smiled the general.

"What do you mean by that?" asked the man from the East Side.

"I mean that upon honor, you shall be released to go in and spend the afternoon and evening with your family in New York. Report to your command tomorrow morning."

The soldier did a very unmilitary thing. He reached forward and grasped the general by the hand, then, pledging his honor, started toward the door.

"Hold on there," said the general.

The East-Sider paused.

"The only train you can get into town is the one-twenty-five. It's ten minutes after one already, and you cannot possibly walk from here to the station in fifteen minutes. My orderly will take you down in the headquarters' car."

After this war is over, I do not believe that we shall have many enlisted men in the service uniform of the United States mowing the grass at barracks and running menial errands for the colonel's wife.

On the day that I walked down Fourth Street, Louisville, I saw many other placards in the shop windows besides those which asked the generous-hearted Kentuckians to subscribe their dollars toward teaching soldiers how to write home or the certificates which showed that this store, or that, was not only sanitary but fair in its dealings with the soldier.

For instance, up at the corner of Broadway, a great dance garden was asking officers and their wives to a series of Saturday afternoon thês-dansants. But the placard added, in an inconspicuous line, "The girls will be specially invited."

This line was particularly significant. Not the tiniest part of the Fosdick commission's problem—perhaps the largest of its "outside camp" activities is the regulation of the sex problem.

Along these lines, it has done wonders. And by exercising but little more than ordinary common sense and hard-headed precautions.

Making John at Home

On the other hand, a lot has been done to bring the soldiers into the association and inspiration of refined women. Down at Montgomery, Alabama, the big National Guard camp had its most extensive help in town, Southern hospitality organized in a "take-a-soldier-home-to-dinner" movement.

Sometimes this has been overdone—some folk cannot attempt things of this sort without making themselves patronizing—but such times have been very much the exception.

The idea has been tremendously successful, not only in Montgomery but also in training camps of the Federalized National Guard or of the new National Army.

From the first, the churches of these towns have opened their lecture rooms or Sunday-school rooms or chapels for the use of the soldiers—not always, I am afraid, with results that were entirely satisfactory to themselves.

Good folk has not seen that this is not a religious revival in all the cantonment towns. This is war. And war frequently is a very different matter from religion.

And yet I would not have you believe that the boys in the training camps are without religion. The contrary is true. A recent Sunday visit to Charlotte, North Carolina, showed every church filled to its doors with the wearers of the khaki.

And yet it was Charlotte— a fine old town of thrifty, stern-headed Scotch Presbyterians—which went through a regular Calvary when Camp Greene was first established upon its edge.

It had Sunday-closing laws of unusual strictness. Yet here were twenty-five thousand guardsmen in town with Sunday leisure and pockets filled with spending money.

You can lead a boy toward church— you cannot drive him in. No wonder that the old town of the Mecklenburg had a tussle with its conscience. But it won. And the attendance in the churches was the direct result.

Books for Johnnie

There is another appeal to Johnnie: through the printed page. The green huts of the Y. M. C. A. are equipped with hastily formed libraries that are not moldering for lack of use.

The American Library Association is cooperating with the Fosdick commission to establish cantonment book centers. And a great deal has been accomplished locally by the town close to the training camps.

At Chillicothe, the excellent local library is under the charge of an experienced writer, Burton E. Stevenson. Chillicothe is not a large city, and the location of a National Army cantonment there has somewhat dazed and discouraged it. But not so with Stevenson.

Almost before the workmen were clearing the site for Camp Sherman, he was collecting books for it. The basement of the little library was made an assembling point for books, and even if an occasional "Little Women*' or "Five Little Peppers" did come rolling in response to the appeal sent broadcast across Ohio, most of the books were bully reading for the average man.

And the newspapers of the state were hardly less generous than the libraries, the publishers, or the private owners of books. They donated five copies of each issue to the cantonment. The war has proved itself already a tremendous stimulus to the generosity of a nation never to be accused of stinginess.

Probably the best of "outside camp" activities has been the foundation of Service clubs, not only in cantonment towns but in various large centers of travel and population.

The regular clubs of every sort and in every type of community have been most generous in opening their facilities to the boys of the Service. But those facilities are, at best, limited. And the demands upon them have been very great.

So special clubs have been created and, in turn, have been nearly swamped under their immediate popularity. As an illustration of this, take the Service Club directly across the street from the Pennsylvania station in New York.

On Wednesday afternoons—Sundays too—four-fifths of the boys at Yaphank are freed from duty. With a particular creditable generosity, the Long Island Railroad makes a rate of sixty cents from camp into New York and back, one hundred and thirty-four miles all told.

The soldiers do not hesitate to take advantage of it. And space in the Service Club goes to a premium. Boys in khaki and navy blue come pouring in from New England and Camp Dix at Wrightstown, New Jersey, as well as the big embarkation camps over near the shore of the Hudson.

There is congestion, which is felt, even in vast New York. And every Saturday night, there are hundreds of soldiers and sailors who sleep all night on the hard benches of the Pennsylvania and Grand Central stations—for lack of a better place.

It is to remedy conditions such as these that Service clubs are being opened in Boston, in Philadelphia, in Baltimore, in Louisville, in Chicago— more of them in New York and many other cities and towns.

There is no lack of provision for John's comfort. Instead, some of the older and more seasoned Army officers frankly express their fear that the thing might be overdone; it was something of a shock to them when they found the boys going to cots and mattresses.

The private of today lives better than the officer in the Spanish War—a mere twenty years ago.

"After all, we must not forget that the cantonments are not outing camps," a grizzled veteran commander told me only a few days ago. "This is not a national joy-ride.

This is war. And the chief business of these cantonments is to make soldiers and make them just as rapidly as it can be done and done thoroughly. Everything else must stand aside and make way for that supreme purpose."

Making American Manhood

There is pith to what he says. And yet, while we have Johnnie in hand, we may make him a soldier and something more—a gentleman, and in the total sense of the word.

That is what the Y. M. C. A. and kindred organizations, the Fosdick commission, and all its functions are doing —with the best of skill and experience that can be found within the entire nation.

They have made a soldier out of Johnnie. They have taken the slouch out of his shoulders and made him stand erect. He is happy; he is well. He is more potent and healthier than ever he has been before. All these things they have done—and one thing more: Uncle Sam has made a man out of his son John.

Edward Hungerford, "Making a Soldier Out of Johnnie," in Everybody's Magazine, February 1918, pp. 39-43; 102-106. Edited for sentence structure, grammar, and spelling.