An American Cantonment - 1919

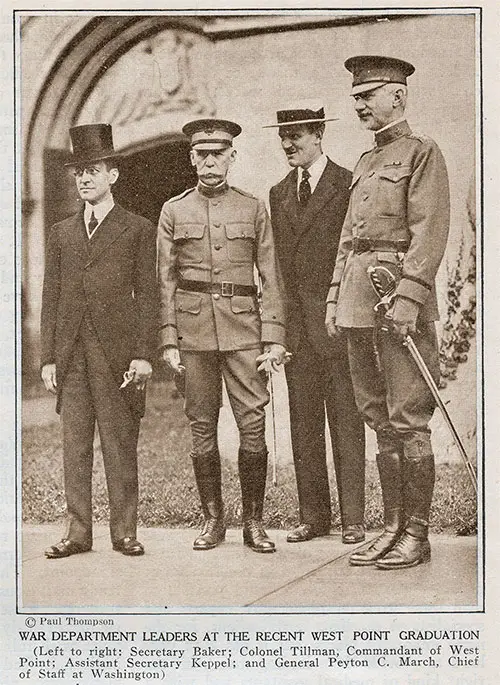

War Department Leaders at the Recent West Point Graduation. Left to Right: Secretary Baker; Colonel Tillman, Commandant of West Point; Assistant Secretary Keppel; and General Peyton C. March, Chief of Staff at Washington. © Paul Thompson. The American Review of Reviews, July 1918. GGA Image ID # 17faf0ab6a

The Impressions of a British Military Correspondent

BY H. CHARLES WOODS, F. R.G.S. (Formerly of the Grenadier Guards)

For reasons that need not be stated here, the voluntary service system seemed the only possible alternative for Great Britain at the beginning of the war. The United States, on the other hand, was committed to the compulsory, or conscription method at the outset. The British student of war who visits an American cantonment is impressed by the contrasting sets of conditions resulting from the two principles in application.

The voluntary system meant for us on the one side an inrush of the very best material existing in the country, and on the other the enlistment of the old soldier, whose presence is hardly ever desirable in a young army, and of the men destined actually to profit financially by joining the Imperial Forces.

This state of things resulted in our new armies being composed of men of widely different quality and age, for in addition to volunteers within the prescribed age limit, there were many who came to the colors though they were above or below it.

The consequence was that units were not only composed of men of greatly varying intelligence, but of a few who, for purely physical reasons, were not able to undergo the same amount of bodily strain or to imbibe knowledge with the same rapidity.

Standing out as markedly apparent to the visitor to an American cantonment are therefore the homogeneous appearance, the almost even age and the uniformly high physical quality of its inmates.

The first of these conditions comes as an astonishment to the stranger, for, when taken together with the inquiries which it is possible to make from different sources on the spot, it proves that the average foreigner, coming to live in America, does so with the object of taking up his abode in and adopting the customs of this country and that the military authorities are not beset, as one would have anticipated they would be beset, by any serious difficulties due to the composite elements of which the population of America is composed.

The even age and the extraordinary healthy and contented-looking faces of the men result from the operation of the draft, from an effective medical examination and service, and from the excellent conditions of life.

It would therefore seem highly desirable to call up every available physically fit man liable under the present draft (only taking into consideration exemptions which are vital), rather than to raise the age limit before this has been done.

The adoption of the former alternative may, for various reasons, cause extra expense to the state and it would certainly result in individual hardship, but, on the other hand, until it be necessary, the inclusion of men who, with only few exceptions, have passed the age rendering them the most fitted to overcome hardship, must automatically decrease the fighting value of the army—a value the maintenance of which is absolutely vital if the enemy is to be defeated at the earliest possible moment.

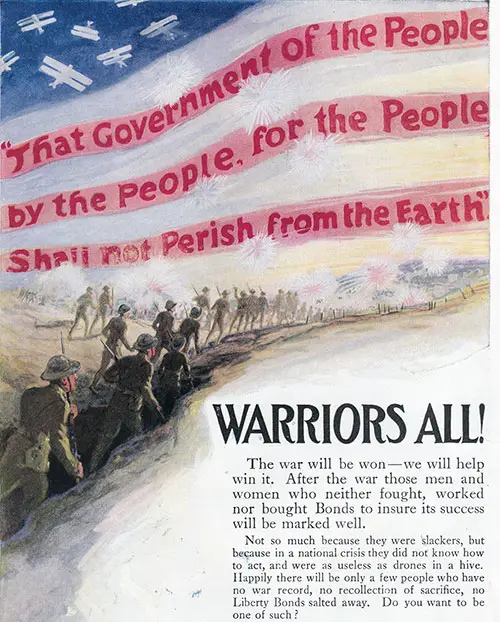

WARRIORS ALL! Advertisement for Libery Bonds, World War 1, The American Review of Reviews, July 1918. GGA Image ID # 17fa743b1e

WARRIORS ALL! Advertisement for Libery Bonds, World War 1, The American Review of Reviews, July 1918. GGA Image ID # 17fa743b1e

Almost equal in importance to the effect of the draft in securing the men of the best physique for the army, is the manner in which they are medically examined and so to speak, practically tested by the Depot Brigade system.

When England first entered the war, owing to the haste with which everything had to be done, some of the recruits, who had passed the original medical tests, had subsequently to be discharged from the service or transferred to special kind of work, owing to some disability which had escaped notice or to their not being sufficiently robust to stand the hardships of their new military life.

The existence of the Depot Brigade, on the other hand, greatly minimizes the danger of this, for it constitutes a sort of clearinghouse, which not only transforms the civilian into a soldier, but also puts him through a fresh medical examination, by those who are cognizant of military conditions, and subjects him to a practical test destined to prove whether or not he is fit for his new military life.

This does not, of course, avoid the intense personal hardship suffered by an “invalided out” man, who has closed up his personal business and made all the arrangements necessary when he is originally called up, but it does prevent the disadvantageous mixing up of the fit with the unfit in units actually destined for the front.

The Depot Brigade principle together with the first-class medical and sanitary services prevailing in camp are largely responsible for the magnificent health of the men.

The excellence of these services is due to the facts that America realized tire desirability of organizing this branch of her service out of formerly civilian doctors, without allowing herself to be hampered by her existing military organization, and that, as everything had to be created new, she was able to lay out her hospitals and military drainage upon the most up-to-date plan.

Thus her medical officers in supreme authority are drawn from men who had a wide reputation and experience as civilians —an experience which enables them not only to effect wonderful recoveries for the sick, but also to give the advice necessary to prevent the general increase of ill-health and to bring about initial cures and therefore to avoid the development of a minor into a serious complaint.

That these are the conditions prevailing is markedly apparent to the visitor who has the opportunity of visiting the magnificent hospital which I saw, of hearing of the scientific research work done in it, and of seeing the great care which is taken —such as the airing of rooms and bedding and the thorough cleaning of all wash-houses—to avoid the possible spread of infection and the propagation of disease.

The outstanding difference between the ordinary American cantonment and the original English war quarters is that whilst we at home have now constructed many camps upon what was militarily virgin soil at the beginning of the war, most of our earlier cantonments, although themselves entirely new, more or less constituted enlargements of and depended upon already existing military centers.

The arrangement of quarters is also somewhat different. For instance, whereas our huts were all on one floor only, the ones which I saw here had two stories. The fact that the American rooms are larger and accommodate more men, and that meals are cooked in the same room as that in which they are served, instead of in a separate cook-house, are also responsible for interesting contrasts in the two systems.

The rations, which struck me as being ample and excellent in every way, are issued in a manner entirely different, and I think greatly preferable to that prevailing in most armies. Thus the recognition of the purchasing power of what is really a financial ration, instead of the allowance of a fixed amount of each commodity per man per day, avoids waste and enables the men to be provided with luxuries to which they are accustomed at home.

It is also interesting to see that the military supper in this country is more of a meal than the so-called ‘‘tea” at home. This has the dual advantage of giving the men a third meat meal in the day and of preventing them from wishing to patronize other establishments where they may get less desirable forms of food and drink than those available in camp.

The various branches of the service are, of course, trained in their particular duties. But what struck me as of great importance is that this training is not confined to the methods of trench warfare, but that the soldier is also taught the art of maneuver and of military operations in the open.

The adoption of this policy is most valuable, for considering the dash and initiative for which the American is worldwide known, and also the fact that it is difficult to believe victory can be obtained merely inch by inch, it will prepare the forces of the United States for war under whatever conditions may arise.

This, when coupled with the number of specialist schools established for the teaching of those themselves intended to become instructors, constitutes the strongest possible proof of the magnitude of idea and conception possessed by the military authorities and of the fact that America and the Americans do not do things by halves.

It is naturally impossible for me to express any comprehensive opinion as to the state of discipline prevailing in the National Army, or as to the extent to which esprit de corps exists.

While obviously and rightly no attempt is made to secure a rigid Prussian spirit, there is that respectful relationship between the different ranks—a relationship which one knows to exist in our magnificent overseas contingents.

Moreover, although the ordinary sergeant mixes more freely with his subordinates than he does at home, this does not appear to have any detrimental effect, and all ranks seem to be able to overcome the difficulty of acting with that tact and wisdom without which inferiors would certainly resent the control of those who are themselves still learning their military duties.

The recognition of the company as a distinct unit, the company organization and the company competitions are, too, the exact means necessary to encourage in the shortest possible time the development of that binding power of tradition which is so essential in every military force.

That this is the case is most important for it proves that the Americans have shown their far-seeing knowledge of human nature in utilizing the company, which is sufficiently large to require a uniting power and yet sufficiently small to enable that uniting power rapidly to grow up, and in thus bring about that state of mind which forms one of the most necessary factors in collective success.

Undoubtedly the first and last impression left upon the mind of the visitor to an American cantonment is that made by its dimensions, and by the difficulties which have to be overcome by the authorities responsible for the training of the National Army.

Thus as one motors from place to place it is scarcely believable that a now military area, more than one-third the size of the District of Columbia, consisted of nothing but wood-

covered hills a year ago. Moreover, instead of those dimensions necessitating great loss of time in getting from place to place, the camp is so laid out as to make superfluous transit unnecessary.

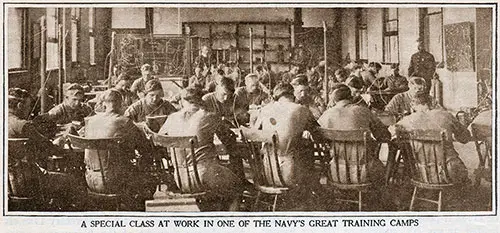

A Special Class at Work in One of the Navy's Great Training Camps. The American Review of Reviews, July 1918. GGA Image ID # 17faa833b3

Again, if America has had certain advantages over England in regard to her facilities in preparation for war, such as those due to the return to this country of officers who have acted as observers with all the European armies at war, including enemy armies, and to the arrival of the various Allied Missions who are here, this country had other difficulties the nature of which are brought to one's mind in camp.

The task of transportation alone, which is being successfully accomplished, is sufficient to prove to the man who knows the meaning of distance by experience, that America is leaving no stone unturned to win the war. And by transportation, I do not mean only or so much the actual question of the passage across the Atlantic—that is an independent problem—but the transportation of men from their often distant homes to camp and from camp to the port of embarkation.

The magnitude of this task is probably not recognized even by the average American who has never been abroad. For, whereas troops can be brought from end to end of France in say thirty hours, or from the north of Scotland to die south of England in say twenty-four hours, here it may rake many days to transfer the recruit from his home to camp or to convey the regiment from its place of training to the port of departure.

Moreover, taken only from the strictly military standpoint, the distance and the lengthy journey which separate the semi-trained or trained American recruit from the Western Front may have their direct effect upon his education.

This is the case because it may well be either that ships are available for the passage before the requisite stage in training has been reached here and that therefore the military passenger loses more than he would later do by a period of practical idleness, or more likely that vessels cannot he provided at the moment when all that can be accomplished on this side has actually been completed.

In short, it is only by a trip to camp that the Englishman can realize the difficulties due to distance, to weather conditions, and to numerous other problems—difficulties which are now being overcome by the Administration of the United States.

Social Facilities in the Army

On the side of social activities and opportunities, the Army is showing most commendable intelligence. Every cantonment has its series of YMCA buildings, where the men may read, write letters, hear music, and enjoy themselves.

There are auditoriums, theaters, and assembly places for lectures and picture shows. The Knights of Columbus are working in their own way, in full harmony with the methods of the YMCA

The Hostess House

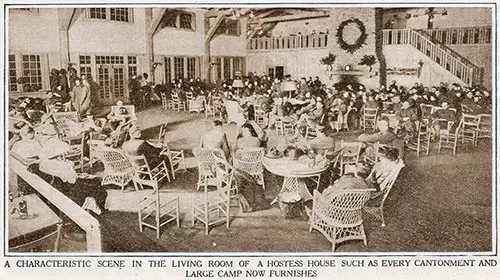

A Characteristic Scene in the Living Room of a Hostess House, Such as Every Cantonment and Large Camp Now Furnishes. The American Review of Reviews, July 1918. GGA Image ID # 17fabcdc49

A remarkable innovation is the institution, found in every large camp and cantonment, known as the Hostess House. This is supported by the Young Women’s Christian Association. Its special object is to provide a place where wives, mothers, or other friends of soldiers may go and wait in comfort, and where their relatives or friends in uniform can visit them and have refreshments with them.

Experience has steadily widened the functions of these Hostess Houses, until their existence in the cantonments is not merely tolerated but is regarded with the highest

favor by the Army authorities.

In the Southern camps and in some of the Northern ones, Hostess Houses are now being provided for colored women, while smaller establishments are being enlarged to meet growing demands. The presence in the Army training centers of the type of women placed in the Hostess Houses by the YWCA is immensely beneficial.

Officers’ wives in considerable numbers become volunteer helpers in these establishments, while many women of high character from cities adjacent to the cantonments give like support to the enterprise.

The Soldiers Libraries

There is no danger of according too much praise to the manner in which the American Library Association has carried out its undertaking to provide in all the permanent camps at home —as well as to our men abroad and to the Navy— suitable library facilities, with well-chosen books and librarians capable of helping soldiers to select reading matter, whether for entertainment or for various kinds of study.

For an improvised undertaking, it would be hard to match this admirable achievement of our modest but skillful American librarians, whose leader in the project has been Mr. Herbert Putnam, head of the Congressional Library at Washington.

Hundreds of thousands of good books have been contributed by the public, while large numbers of necessary books have been directly purchased. Everything is carefully sorted and classified before it goes to the library shelves in the various camps.

Typical Cantonment Hospital

Greatest and most impressive, however, of all the cantonment agencies and facilities is the establishment known as the Base Hospital. Here again we find first a great conception and then a splendid struggle to realize it.

The chief mistake of our cantonment system at the start was the failure at Washington to perceive that physical conditions as respects environment and the health of the men themselves are of more primary importance in developing a training establishment like one of our cantonments than the strictly military work.

The cantonments were demoralized last fall and winter by terrible epidemics of pneumonia, not to mention scarlet fever, measles, and a hundred other maladies. Many deaths resulted, because the hospitals had not been completed or properly equipped, and because the great surgeons and physicians in charge of these hospitals had not sufficient authority.

These dreadful mistakes will be duly recorded in the medical and surgical history of the war. They are now, happily, almost overcome and lived down. The Army medical service is a triumph in spite of obstacles, because the men at the head of it are the most capable professional men in the whole world.

A typical base hospital in one of the regular cantonments may be regarded as extending over an area perhaps a mile long and half a mile wide, this space being covered with pavilions and wards, suitably grouped, well fitted for their purposes, and with various laboratories and special facilities.

Recruits arriving in these cantonments from town and countryside are given careful medical examination. In the Southern centers, for example, they are examined for hookworm and malaria, while they are also, of course, vaccinated against smallpox and inoculated against the different forms of typhoid.

The hookworm cases are exceedingly numerous, and they are all treated by the methods which were adopted and set in motion a few years ago by the Rockefeller International Health Commission. The men are completely transformed by medical treatment and Army life.

In one of these Southern camps (Camp Jackson, at Columbia, S. C.) a distinguished New York physician, Major Herrick, has had remarkable success in reducing the mortality from meningitis by the serum treatment; and thus research goes hand in hand with applications of established methods in these vast hospitals.

During the coming winter we may hope for a great reduction in the ravages of pneumonia. It has been found possible to man these great hospitals with experts and specialists of excellent qualifications, for the more important places, but it has been very hard to provide these leading men with the right kind of medical assistants and with a sufficient number of well-trained nurses.

H. Charles Woods, F.R.G.S., "An American Cantonment," in American Review of Reviews, New York: The Review of Reviews Co., Vol. 58, July 1918, p. 50-52.