War Hello Girls Talking - We Win! -1918

If Message of Victory Could Be Telephoned from France. Signal Service Operators Training Here for Service Overseas, Would Plug in Capitol City in Record Time—Girl Brigade Awaiting Call to Help Pershing's Army. Studying Under Military Discipline—War Not New to Some of Company—"Win the War," Their Motto.

At the Highland Court Hotel are quartered twelve young women. This is not remarkable, but these twelve are in the service of the United States Government, eleven of them as telephone operators and the twelfth, an inspector sent here from New York to check up the work of the eleven.

For the eleven will form a part of the contingent of young women from America who responded to the call of General "Jack" Pershing, commander in chief of the American armies In France, for experienced telephone operators, familiar with English and French languages, and trained to the minute for army work. Hartford has reason to be proud of the part it plays in fitting these young women for service overseas.

Signal Service Operators

A more determined gathering of young women would be hard to find. They say they are not "hello girls" if you please, but United States Signal Service operators, and glory in the fact that they will soon be in France doing their big little bit in the Army of civilization as ever before.

With their snaps and dash, however, they will become known as "Wat Hello Girls." With difficulty, an interview was obtained with the young women, even though the reporters assigned to the work elected to call on a Sunday afternoon. The girls shun the limelight of publicity. They have the "Posy" sign up all the while. "Win the war" is their motto.

The Message They Want to Send

In these days of modern inventions, it is not beyond the realm of possibility that the telephone may carry a voice message across the ocean as it has carried it across the American continent.

If this progress in telephonic conversation comes when Germany is beaten in an ultimate battle, we would not be surprised to get the following message from our friends, the war-time telephone girls:

"Hello, Hartford, war-telephone girls talking: We win!"

Enthusiasm? Plenty of it, and then some, for the much-abused, supposedly gum-chewing telephone girl, has been changed into a soldier from tip to toe. In the big Loyalty parade on the Fourth of July, one of these young women insisted that the flag of her native country, Belgium, must appear and must be carried by a Belgian.

Those who remember the parade have visions even yet of the determined appearing young woman who marched the miles over the hot pavement, carrying the flag with never a faltering step. However, the day was hot, and the government had not yet provided the little telephone army with summer uniforms.

Enthusiasm? Evidence of it was apparent when the flashing eyes and clenched fist one of the French girls expressively announced, "We Will Win," with something similar in her tone to the determination voiced by her brothers in the field at Verdun when they declared, "Ils ne passeront pas," (They shall not pass.)

She's Putting Her "War Hello Girl" Brigade in Trim to Beat [the Germans]. Introducing Miss Catherine Byram, Supervisor of the Brigade of Telephone Signal Girls Training in Hartford. When Miss Byram Has Completed Her Work of Supervision, She is Going Across the Atlantic With Her Command. The Hartford Currant, 18 August 1918. GGA Image ID #

Have No Use for Germans

For Germany and the Germans, they have no early use. They could see nothing in the suggestion that undoubtedly many in Germany regarded the war from the same viewpoint as themselves and did not voice their opinion because they dared not.

"There is nothing German that is good," was the way one put it, and though three of them can speak German fluently, they never use it now for reasons that one could not better express than the remark of one, "we would so soil our tongues."

"If you knew Germany and the Germans as we know them, you would feel just as we do about it," another said.

The operators have been most courteously received in Hartford. At the recent ball given in the State Armory by veterans of the Spanish-American War, the young girls had a place of honor in the grand march. In appreciation of their participation in the event, the veterans recently presented to each a handsome swagger stick, on the head of which was the veterans' military insignia.

The call for telephone operators for foreign service was sent out through the newspapers of the country by the chief signal officer, who supplied the qualifications needed by applicants, among them, to be able to speak English and French fluently, attracted girls from all over the country, some from patriotic motives alone, others through that spirit of adventure, ever-present.

But the adventurous soon were discovered and weeded out. The iron rule from which the selections are finally made is clear from the fact that of 1,100 who presented themselves in New York on a single day for examinations, the Army selected only 150 for the tests.

These were examined as to French and English, the cause of their desire for service, and their private lives almost from birth. Finally came a physical test before the U.S. swore the girls into government service.

Their rank is similar to that of a sergeant major in the Army, the highest non-commissioned officer. In addition to their regular pay, they have a liberal allowance for expenses.

One could not talk with the young women who are undergoing "intensive training" in Hartford but understand at once that these girls are thoroughly sincere and will be a decided help in the big scheme of efficiency which will bring Germany to her knees.

In France, they will be "toll line" operators. In preparation for this service, they are devoting much time each day to geographical study, one of the principal requirements of their work.

The Training System

One of the girls volunteered the information that she had spent twenty-nine hours last week studying French Geography. On account of her familiarity with the section where the western battlefront is, she was thus engaged less than any of the others.

They are required to send a weekly written examination to the war department, in addition to the eight hours a day at the telephone office. The geography course consists of forty-five lessons and nine reviews, five lessons, and one review each week.

These girls have distinctive uniforms, their summer suits having just been received. They have two hats, one of velour with a brim, the other of the same material as the uniform and not unlike the aviation cap in appearance; a full-length ulster, lined and interlined, a suit coat or blouse, walking skirts, and extra high tan shoes.

Gave Up Art For War Service. Miss Aurelie Asten Is a Clever Caricaturist and Plans To Be a Cartoonist and Illustrator When the War is Over. The Hartford Courant, 18 August 1918. GGA Image ID #

Miss Bram Brings Good News

It was Miss Catharine A. Byram, a member of the Sixth Unit whose experience as an instructor for the American Telephone and Telegraph Company at Cleveland, Ohio resulted in her appointment by Major John Moore to the position of instructor of the girls in this unit, who brought the glad tidings to the girls in training in this city that it had been definitely settled that the unit would sail in the fall.

Miss Byram's duties carry her to Trenton, New Jersey, Philadelphia, Camp Dix in Wrightstown, New Jersey, Langhorne, Pennsylvania, Atlantic City, Wilkes-Barre, PA, Scranton, PA, New Haven, and Hartford, in each of which cities a certain number of the Sixth Unit are in training.

She left Hartford about a week and a half ago and went to New Haven. While in Hartford, she arranged for the girls' vacations, each being entitled to one week, and the fact that the girls were informed that all vacations must be over by 1 September was a source of gratification to them, for they felt that this alone was a sign that they are soon to go to France.

Miss Byram was born in Asbury Park, New Jersey but has spent the more significant part of her life in New York, Boston, and Cleveland; it is in the latter city that she enlisted in the Signal Corps.

She attended Simmons College in Boston and spoke French fluently. She has two brothers in the service, George Byram in the ordnance department and Holbert Byram in the naval aviation section.

Her mother, Mrs. Anna Byram, lives in Waverly, New York. Before her enlistment, Miss Byram was an active worker in Red Cross branches, but being desirous of more active service in which her knowledge of the French language might also be of benefit, she mad application for the Signal Corps after being informed that one unit of telephone operators had already sailed for France.

Miss Byram explained the duties of the girls in the corps and said that while it was disappointing to all of them to be left on this side [of the Atlantic] for such an extended period, their duties on the other side of the water require more training than the duties of those girls in the units that have already sailed.

Thus far, six units have been organized. Five are already overseas, four engaged in local service, and one on toll service. The sixth unit is also a toll service unit.

The members of the sixth unit have not had any military training yet but will be trained during their last week in this country and on shipboard during the trip overseas.

All promotions are made overseas, Miss Byram explained. The girls in the unit are to be classed as officers, the operators to be ranked as second lieutenants, the supervisors as first lieutenants, and the chief operators as captains.

To Avenge Brother's Death

An advertisement appearing in one of the New York papers calling upon young women between the ages of 19 and 35 years, capable of speaking French and English, to enlist in the Signal Corps for overseas service as telephone operators, first attracted the attention of Miss Jeanne Bourquin, one of the eleven members of the Fifth Unit of the corps at present in training in Hartford.

Miss Bourquin's 22-year-old brother, Fernand, fell at Arras in 1915, and ever since that time, she has been trying to get into some branch of the service, return to her native land, and "do her bit" in avenging his death.

She lost no time in replying to the "ad," sending her application to Washington. Much to her disappointment, she received a reply stating that there were no openings at present but that the Signal Corps would place her name on file.

This was in January of [1918]. Week after week passed, and she had about given up hopes of ever hearing from her application again. In the meantime, she left for a trip to Virginia.

In Virginia, she received a telegram, summoning her to New York to undergo the examinations required of applicants for the corps.

One Out of 500

Out of the 500 New York applications, Miss Bourquin was one of the successful ones, receiving her appointment on 1 March. Before coming to Hartford, she trained in New York and at the army piers at Hoboken, New Jersey.

When she made an application to become a member of the corps, Miss Bourquin was living with her mother, Mrs. Emma Bourquin, and her 15-year-old brother, Edmond, at no. 237 West 24th street, New York. Her brother, Fernand, too, was living in New York at the outbreak of hostilities with Germany, but he returned to France at once, enlisting in the 171st Regiment of the French Army.

This division was nearly wiped out in the fighting at Arras in 1915, and Miss Bourquin has tried in vain to get in touch with a survivor who might know some of the details concerning her brother's death.

She has communicated with a few of those who still are of this division, but thus far, the only information she has been able to secure is that "he left camp for the front-line trenches on 18 May and disappeared on 25 May 1915."

I would feel like a slacker if I did not go," said Miss Bourquin, "because there is no one else in my family now that could go, my [other] brother being too young."

Each of Miss Bourquin's two uncles has also lost a son in the fighting in France. At the time of enlistment, Miss Bourquin was engaged in New York as a French tutor. She lived in Chicago before coming to New York.

Belgian Girl Escapes Germans

Fleeing from Brussels, Belgium, on the last refugee train and just twelve hours before the arrival in Brussels of the German Army was the experience of Miss Gabrielle Toby, who with her sister, Miss Helene Toby, are the only two Belgian girls in training in this city.

Miss Toby, however, declines to relate her most exciting experiences. Still, from her sister, it was learned that it was at 8:00 pm on the evening of 20 August 1914 that Miss Gabrielle left Brussels for a safer clime on a train that carried the last of the refugees from the city before the arrival of the German Army at 7:00 am the following morning.

Miss Helene Toby has been in America for almost eight years and was at Newport, Rhode Island, at the time of the arrival of her sister about four years ago.

The Germans have ravaged the beautiful home of the Toby’s in Belgium, and Miss Gabrielle was forced to leave home without any of her belongings, arriving in this country with only the clothes that she wore.

The girls' mother is now in France, and they have cousins serving in the Belgian Army. An aunt, now in America, had similar experiences to those of Miss Gabrielle's in getting safely to American shores.

Under German Rule Eight Months

While at Newport, Miss Helene Toby received word that her aunt had managed to elude the watchful eye of the enemy and make her escape to the point of embarkation from which she sailed for America.

Miss Toby's aunt had even more exciting experiences than Miss Gabrielle Toby, for she lived in a town that the Germans had taken for nearly eight months.

She chanced to hear of a means of escape from Brussels, but after walking three days and nights in all kinds of weather, she arrived at the destination with many other refugees, only to find that the Germans were carefully guarding it.

This only meant the return journey of three more days and nights and a still more extended period of living under the watchful German eye. On her next attempt, however, she was successful in reaching a point of embarkation for refugees.

Gives Up College to Enlist

Miss Sophie Lefebvre, one of the American-born girls in the unit, after reading in the newspapers that a unit of telephone operators had sailed for service with Pershing's forces, abandoned her studies at Cornell University, where she was studying law, and enlisted in the Signal Corps.

Miss Lefebvre is the only daughter of Mr. and Mrs. A. Henry Lefebvre of Watertown, New York, and gained her knowledge of the French language at Outremont Convent in Montreal, Canada.

She received her appointment in the corps on 1 April 1918 and, before coming to Hartford, was in training at the army building in New York.

She is equally as desirous for overseas service as the foreign-born members of the unit themselves and declares that she will make her presence felt if given the opportunity.

"Zeps" Ruined Father's Factory

Miss Ruth Asten, born in Paris, was pursuing a course of study at the Harvey Dunn Illustration School at Leonia, New Jersey, when she was informed through the newspapers of the formation of several Signal Corps units and as one of her greatest desires has been to "kill a Fritz," she lost no time in making application for appointment.

"The Courant" man who interviewed Miss Asten will vouch for the accuracy of the statement that she was "pursuing a course of study in illustration" and that her pursuits have not been in vain, for while listening attentively to her experiences as she related them, he was surprised to find that Miss Asten had about completed a sketch of the reporter in a characteristic pose. Before coming to Harford, Miss Asten spent a week at Camp Merritt, New Jersey, in training.

Unlike the rest of the French girls of the unit, Miss Asten's greatest desire upon arriving overseas is to visit England, for it was in London that she spent a more significant part of her life.

She has spent considerable time in America, but her visits to France and England have been frequent. Her father is in London at present, and during a Zeppelin raid over the city, the Germans destroyed an incandescent mantle factory of which he was the owner.

Two Girls "Out O' Luck"

To Miss Ruth Clarke and Miss Mathilde Ferrié, both American born girls was the announcement of Miss Byram that the unit would surely sail in the fall especially pleasing for had they not been "out o' luck." as it is expressed in army terms, both would now be on French soil.

Miss Clarke and Miss Ferrié are members of the fourth unit and were already to sail with the unit with orders from Washington "cut the unit eight" and of the eight who were unfortunate enough to be left behind, they were two.

And for no other reason than that, there were no accommodations. In selecting those to wait for the next unit, it was considered advisable to take the newer members of the unit as, of course, the others had the advantage of more training.

Miss Clarke was born in Billings, Montana but her love for Oregon, in which she has lived the greater part of her life, prompts her to term herself an "Oregonian."

She is a daughter of I. W. Clarke of Billings and has a sister, head of a British Red Cross canteen, another sister in Billings, and still another in Portland, Oregon.

She has traveled extensively, having visited England and Switzerland. She was in Oregon at the time of her enlistment in the Signal Corps and trained for a time in San Francisco.

Lost Home in Earthquake

Miss Ferrié was born in San Francisco, and her great desire is to visit Lille Upon her arrival in France, for she has already made two trips to France, visiting Lille on each occasion.

She is desirous, too, that her duties as an operator will take her to an old French castle which she finds extremely interesting. During the disastrous earthquake in California, her home was destroyed.

At present, her mother, Mrs. Marie Bodin, lives in San Francisco. Miss Ferrié enlisted in San Francisco, receiving her appointment on 1 March 1918.

Miss Couleru's Experience

The arrival of a German submarine in the Harbor of Le Havre on the day on which her ship was to have sailed for the United States offered a little excitement for Miss Gilda Couleru, the second Paris-born member of the unit in training here.

Still, she merely refers to the incident as a typical everyday affair, saying that after the "sub" had sunk two coal barges, the passenger of the ocean liner disembarked and "just waited over a day" before starting the voyage to American shores.

She has a mother and three sisters, Renée, Marguerite, and Marie, living in Paris. The last-mentioned sister has opened a Red Cross library for soldiers.

In Speaking of air raids, Miss Couleru says that it is nothing unusual for her mother and sisters to sleep for weeks at a time in their clothes.

When German airplanes are detected in the vicinity of a French village, a warning is sounded by men who cover the village by motorcycle, and at once everyone rushes to a shelter house provided for protection against such raids.

These shelter houses are erected at several points about the village, and each family has its designated shelter.

Miss Couleru also spoke of the ruins brought about by the Germans’ long-range gun but said that fortunately, her home was not in direct range of the gun. Gas Attacks are frequent, she says, and many families have gas masks in the living room ready for instant use.

Miss Couleru has been in America for ten years, during which time she has made many trips to her native land. On one trip, she took her pet dog, "Snookums," as a present for her mother.

"Snookums" is a survivor of many an air raid, and while the French people living in the towns close to the fighting lines have been forced to kill many of their dogs, "Snookums" is still among the living. Miss Couleru received her appointment to the signal Corps on 1 March 1918, and before coming to Hartford, trained at Camp Upton, Long Island, and the Long-Distance School in New York.

She has been engaged as a French instructor, and for her to offer services to the government, she was taking a course in stenography.

She preferred, however, to get into some branch of the service where her knowledge of French might be of value, and when news of the formation of the Signal Corps came to her, she immediately applied.

Her Brother the Bold Aviator

If there are many French aviators like Lieutenant Georges Champrigand of the Twelfth Escadrille, a brother of Miss Helene Champrigand, who gave up French tutoring in New York to enlist in the signal corps, the current stock of [German] airplanes must be sadly depleted for lieutenant Georges has brought down eleven of them.

And Lieutenant Georges and Miss Helene are not the only members of the Champrigand family who are "doing their bit," for the French government, another brother, Pierre, is a sergeant in the Forty-Seventh French Artillery and fought gallantly in Alsace-Lorraine and still a third brother, Georges Edouard is in one of the engineering divisions of the French Army.

Pierre is only 19 years old and Georges Edouard 22, but both have been fighting since the outbreak of the war in 1914. Miss Champrigand's sister, Miss Angele Champrigand, was not content with simply being a nurse, so with Miss Eugenie Buisson and Miss Laure Charpentier, two other French girls with the interests of their native land at heart, opened a hospital at Compiegne with accommodations for twenty-five soldiers.

The last time Miss Helene heard from her sister, the hospital had increased the twenty-five beds to 139, and the number was still going up.

Having heard of the demand in her native land for girls who knew the French language, Miss Helene Champrigand sought to enlist in the signal corps, for she had already read in the newspapers of the departure of some of the earlier units.

She was in New York and was first referred to N. C. Kingsbury, vice president of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, and later to A. A. Field, who oversees the recruiting in New York. Having passed the required examinations, she received her appointment on 11 March [1918], and before coming to Hartford, spent two weeks in training at Camp Merritt, New Jersey.

Paris and New York

It was Miss Champrigand, who, when asked to give her opinion of New York as compared with Paris, expressed it by saying, "in New York, the people rush to their graves." Nevertheless, she loves America the best, next to her native land.

She has been in America for eleven years, during which period she has made ten trips to France. She, too, has gotten into New York's ways of "rushing," and she says, "the folks at home are shocked at me for rushing through my meals the way I do when in France."

She spoke of the laxity of the American people on occasions when the Stars and Stripes are present, saying that she was amazed on several occasions to see men who keep on their hats as the flag passed.

"In France, if they did that, they would be mobbed," she said. Miss Champrigand is equally as eager for overseas service as the rest of the unit quartered here and outwardly expressed just how deep her desire is to see her native land once again when she said, "it is mean to keep us here so long."

Miss Champrigand's parents live in Lure, where her mother lends assistance to her father, who is busy with his government duties. She was born in Nice. Her last trip from France to America was made on the Lusitania, not long before that vessel was sent down by a German submarine.

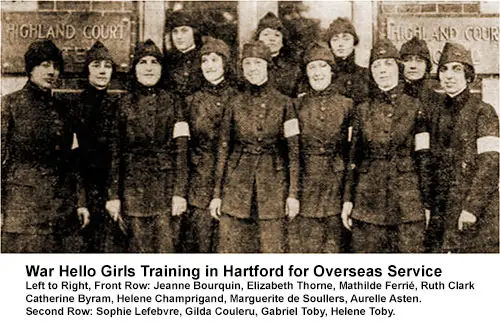

War Hello Girls Training in Hartford for Overseas Service. Left to Right, Front Row: Jeanne Bourquin, Elizabeth Thorne, Mathilde Ferrié, Ruth Clark Catherine Byram, Helene Champrigand, Marguerite de Souliers, Aurelle Asten. Second Row: Sophie Lefebvre, Gilda Couleru, Gabriel Toby, Helene Toby. The Hartford Courant, 18 August 1918. GGA Image ID #

Fitted for Work

Feeling that she might be of more benefit to the government in service overseas where she could use her knowledge of the French language to advantage, Miss Elizabeth F. Thorne, who had been doing a noble work among the men at the different cantonment, arranging for their entertainment, etc., abandoned this work and on Washington's Birthday, applied for admission in the signal corps.

She was successful in all the required examinations and received her appointment on 11 March 1918, assigned to the quartermaster's department in New York for training before her arrival in Hartford.

Miss Thorne was born in New York and came from a patriotic family. Her mother, Mrs. Marie Thorne, lives at Camp Devens and is an ardent Red Cross worker.

She has a brother employed in the shipyards at Hog Island, Philadelphia, and four sisters, Mrs. C. Z. Overstreet, Mrs. Lawrence P. Moomau, Mrs. G. W. Mauer, and Miss Marie Thorne, who expects soon to sail for overseas to engage in Red Cross canteen work. Mrs. Overstreet's husband is a lieutenant in the engineering corps, now overseas, and Mrs. Mooman's husband is also a lieutenant at Camp Upton, Long Island.

Like Miss Asten, Miss Thorne is an enthusiastic devotee of art and a Smith College graduate. Miss Thorne and Miss Asten had met previously at an art club in New York. The former has done considerable settlement work in New York and speaks French, Spanish, Italian, and English fluently.

"Surely We'll Win."

Miss Marguerite de Saulles was in Belfort at the time of the outbreak of the war and went to Switzerland to live with her married sister, later coming to America and living in Boston.

She attended Boston University, and at the time of her enlistment in the telephone unit, she was engaged as a French tutor.

She was born in Belfort, the only part of Alsace left to the French after the war of 1870, the daughter of Henri de Saulles. She has two brothers in the service of France.

Georges, a lieutenant in the aviation section of the French Army, who, because of wounds received while in action, is now engaged at an instruction camp, and Jean, a sergeant in the Thirty-Sixth Artillery.

Jean is 23 years of age and was just ready to begin his three years of military training, as required by the French government when the war broke out with Germany.

Like so many of the other girls, Miss de Saulles gained her first knowledge of the formation of telephone units through the newspaper and lost no time in getting the necessary application blanks, receiving her appointment on 8 March 1918.

She, too, trained at an army camp before coming to Hartford being assigned to Camp Upton, Long Island, where she spent two weeks.

One would dispel any doubts about the war's outcome after talking on the "big" questions with Miss de Saulles, for she very enthusiastically and optimistically said, "sure! we'll win," when asked for her opinion.

"Hello, Hartford! War Hello Girls Talking: We Win!" in The Hartford Daily Courant, Sunday, 18 August 1918, pp. 2-X, and 7-X (War Section)