Facts Surrounding the Enlistment and Service of the Signal Corps Telephone Operators - 1977

Telephone Operators of the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania, at Camp Dix, New Jersey. Circuits of Victory, 1921. GGA Image ID # 199f93401a

The following has been edited for clarity and brevity whenever possible. After reading this, the facts remain. One should be able to form an opinion about whether the "Hello Girls" were classified correctly as civilians or reclassified as Army enlisted personnel.

Prepared Statement of Mark M. Hough

It is a privilege for me to present this statement to this distinguished Committee. Thank you for extending the invitation to me to comment on S. 1414, which would give official recognition of the military status of the women of the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units during the First World War.

A brief introduction: My name is Mark M. Hough. I am an attorney. I practice law with the firm of Schweppe, Doolittle, Krug, Tausend & Beezer in Seattle, Washington. I make this statement solely out of my belief that a gross injustice has been done to the women of the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units. I am presenting my views on behalf of these women.

I have not been and will not be remunerated for my support. For some time, I have had a deep interest in the United States military history of the First World War era. I have collected much historical information about various units in the American Expeditionary Forces, but I had never heard of the Signal Corps women until, in the fall of 1975, I read an article about Merle Anderson and these women in the Seattle Times. I have attached a copy of that article to my statement. (attachment 1).

After reading the article, I contacted Merle Anderson. We reviewed her records, and she explained her efforts over the years to gain recognition for the military achievements of these women. I became intrigued.

Since then, I have contacted other Signal Corps women. I have obtained many documents pertaining to their service, and I have thoroughly examined the official records pertaining to the Telephone Operating Units, which are now in the National Archives in Washington, D. C.

On the basis of the information which I have gathered and reviewed over the last year and a half, there is no question in my mind that the Signal Corps Telephone Operators morally and legally are entitled to official recognition of their military service in the United States Army. To my knowledge, their story is unique, as well.

The Facts Surrounding the Enlistment and Service of the Signal Corps Telephone Operators Conclusively Prove That They Served in the United States Army.

The theme of this statement is that it is not what you intend to do but how you do it, which is essential.

There is little doubt that the orders that authorized the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units organization contemplated that the women would be civilian employees.

Still, the evidence is overwhelming that the women were not hired as civilian employees of the Army but were enlisted as bona fide members of the military establishment.

In all essential respects, the Army treated them as military personnel, and by the Army's acts, they became military personnel. This fact sets the Signal Corps Telephone Operators apart from all other civilian groups, of which I am aware, which have sought or may in the future seek military status.

To fully understand how the Army recruited the telephone operators, some background information is necessary.

Background Information

Our entry into the First World War on 6 April 1917 found the nation ill-equipped for War. Not only were the combat units of the regular Army inadequate, but the specialty units so necessary for modern warfare were practically nonexistent. The War Department made urgent appeals to various industries to raise specialty units for military service in the United States Army. Industry in the United States gave a genuinely patriotic response.

Thus, the timber industry raised several regiments of forestry engineers, the 10th, 20th, 41st, 42nd, and 43rd Engineer Regiments. From the nation's railroads came several regiments of railroad construction and operating engineers; for example, the 11th through 19th, and 21st through 24th Engineer Regiments.

The mining industry supplied a regiment of mining engineers, the 27th Engineers. Hospitals and medical schools provided 51 base hospitals, first under the auspices of the Red Cross, later with full military status, for instance, Base Hospital 5 from the Harvard Medical School and Base Hospital 6 from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The nation's telephone companies responded by raising several battalions of telephone and telegraph construction and operating units. For instance, New England Bell supplied the 401st Telegraph Battalion, while Pennsylvania Bell supplied the 406th Telegraph Battalion.

The military status of these units, specialists though they were, and even though they did not follow in every instance traditional military organization tables (the 20th Engineers had, at one time, 24,000 men in its ranks and was touted as the largest regiment in the world), was never questioned. Women had served in the Army only in the Army Nurse Corps, formed in 1901.

Against this background, it was not at all out of place for the Army to announce that it needed a unit of telephone operators who could speak fluent French and English for service in the American Expeditionary Force.

General Pershing's Request

Telephone operators in those days were exclusively women. Thus, if the Army wanted trained telephone operators in a hurry, those operators had to be women.

General Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary forces in France, had had a firsthand opportunity to review the service of the telephone operators of the British Women's Auxiliary Corps, an authentic military formation in the British Army. He cabled (Note 1) the War Department with an urgent request for a similar unit comprise of American women. (See attachment 2 and attachment 3(i)).

General Pershing's request of 10 November 1917 was affirmatively acted upon by the War Department. I have attached copies of the relevant memoranda of the Adjutant General concerning the organization of these units.

The War Department, it is clear from these documents, intended that the women would have to be civilians. It is not clear why the Army reached this decision; presumably, there was a question as to whether the Army had the legislative authority to enlist women. It is unclear whether or not it had such authority.

Still, the Navy and Marine Corps, faced with the same interpretive problems, decided to enlist women. Many women served faithfully in the United States Navy and Marine Corps. However, they all served in the United States and not abroad. (See attachment 2)

In any event, it is instructive to review these documents from November 1917. Paragraph 2 of attachments 3(iii) and 3(iv) contemplates that the women of the Telephone Operating Units would be civilians.

It indicates that they would have certain privileges and allowances that the Army might prescribe for Army nurses. Still, it shows further that because these privileges and allowances were to be given to contract employees, they had to be specified in detail in the contracts under which Army engaged the employees. This was necessary because Army regulations would not cover civilian employees. So far, everything seems clear.

Ambiguity Sets the Telephone Operators Apart

But right away, ambiguity as to their status crept into the picture. Look, for a moment, at attachment 3(v). This is the proof for the General Order, which authorized privileges and allowances. Notice that there is no reference to a contract as specified by the Adjutant General; instead, there is a discussion of Army regulations and general orders.

Enters now a young Signal Corps officer, First Lieutenant (later Captain) Ernest J. Wessen. Lt. Wessen was placed in charge of obtaining the operators.

By his admission, he was an "action" man. We are fortunate to have a letter from him to Merle Anderson (attachment 4), written on 14 August 1950, commenting on legislation before Congress.

The fact that the telephone operating units were expeditiously recruited shows that, indeed, he "got the job done," but, by his admission, it was not one in the manner prescribed by the Adjutant General.

Instead of preparing a formal contract as envisioned by the War Department, and instead of notifying the nation that the Army needed civilian contract employees, Lt. Wessen prepared and disseminated a notice under date of 11 December 1917, a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock.

Lt. Wessen disregarded the Adjutant General's directive, and the notice of 11 December 1917 is anything but an offer for contract employees.

Nowhere in the notice is there an indication that women are sought by contract. On the contrary, Lt. Wessen states, "This unit will be very similar to the British Women's Auxiliary Corps, the Signal Branch of which has gained considerable fame in France." This British Army unit was the one that so impressed General Pershing.

Lt. Wessen went on to state that after describing in detail the proposed Army uniform to be worn by the women, "this will be the only unit composed of women that will wear Army insignia."

In this aspect, I believe Lt. Wessen was correct. I am unaware of any other uniform worn by civilian contract employees, which included the official insignia of the United States Army.

Lt. Wessen's letter to Merle Anderson (attachment 4) makes it clear beyond a doubt that the publicity and announcements, and requests for volunteers for the telephone operating units never was made in the context of civilian employees.

His letter shows beyond a doubt that he was in many ways individually responsible for the confusion over the status of the women, and he expressed his desire to set the record straight (attachment 4(iv)). Unfortunately, this is the only statement by Lt. Wessen which we now have since he died several years ago.

One cannot deny that Lt. Wessen created much confusion over their status. Witness this legislation and all the legislation that has preceded it. Confusion about the telephone operators' status existed within the Army.

As late as 30 July 1918, Brigadier General Russel, Chief Signal Officer of the American Expeditionary Forces, was seeking clarification from the War Department as to the actual status of telephone operators, many of whom were already on duty in France, some in advance headquarter units (attachment 5).

Notices, Appointments, and Orders

Many women responded after the Army Signal Corps' original announcement of their intent to form a telephone operating unit. One of these was Adele Hoppock, then a senior at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The documents about her enlistment are attached to the affidavit of her sister, Gertrude Hoppock. One can take this correspondence as typical of that between the War Department and all applicants for service in the telephone operating units.

The correspondence from the War Department is devoid of any reference to a contract or civilian status of the women applying. Note Exhibit B. 1) A physical examination was required; 2) the Army ascertained French-speaking ability, and 3) the Army requested other pertinent information.

Exhibit C again is devoid of any reference to a contract or civilian status. Exhibit D -- Gertrude Hoppock's appointment to the Signal Corps is again devoid of any reference to a contract or civilian status. (This, incidentally, shows receipt of a Veterans' bonus of $285 from Washington State .) (See also Exhibit B to the affidavit of Enid Pooley.)

Exhibits E and F are telegraphic orders issued under the authority of the Secretary of War. The travel directed is necessary for the military service. The transportation allowances are the same as prescribed for Army nurses in Army regulations. (See Exhibit 1 to the affidavit of Oleda Christides; Exhibit 2 of affidavit of Louise Maxwell.)

These documents are by authority of the Chief Signal Officer of the United States Army on War Department letterheads, signed by a Captain in the Signal Corps of the United States Army.

After their acceptance into the telephone operating units, the women shared similar experiences, as evidenced by the affidavits I have submitted today.

The Women are Sworn Into Military Service

Following official acceptance, They indicate that the women were sworn in by some official, either Military or acting on the Military's authority.

Merle Anderson, for instance, was sworn in by the Adjutant General of the State of Montana, General Greenan (affidavit of Merle Anderson).

The Seattle women were sworn in by Major Newell, a Signal Corps Reserve Officer, then working for Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Company (affidavit of Marjorie McKillop and affidavit of Enid Pooley). A General who was a family friend swore in Olive Shaw (affidavit of Olive Shaw).

The women then traveled and lived under Army orders from the time of their acceptance until their termination from the service. Their travel orders and per diem allowance orders read "same as Army nurses in Army regulations."

No Contract Signed

Signal Corps Telephone Operating Unit members never signed any contract. Nor were they asked to sign contracts. No agreements were ever prepared, much less presented to be signed.

This is clear from attachment 6, which the Senate prepared for a report on S. 2240 in 1932. The response was from the Chief Signal Officer to secure, among other things, the following information: "Whether or not all or any part of the personnel described in the Bill signed any special contract with the Government for their service overseas." The Chief Signal Officer's response, "No contracts signed."

Military Regulations and Penalties Prevailed

While in the service, the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units women were subject to military discipline and military regulations. Olive Shaw states in her affidavit that one woman was court-martialed.

The affidavits also show that the women were instructed in close order drills and Army discipline. The Army prepared a unique set of military regulations to govern the operation of military switchboards.

These regulations are included in attachment 7. You will notice no reference to contract status in those regulations. On the contrary, everything about them is military.

The regulations and affidavits of the women make it clear that they wore uniforms which included regulation military insignia and buttons.

The accompanying affidavits make it clear beyond question that the women in the telephone operating units regarded themselves as strictly military.

The letter from Adele Hoppock to her mother, reprinted in The Pacific Telephone Magazine, July 1918, and marked as Exhibit N to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock, confirms it.

Exhibits O-T, BB, CC, and attachment 14 are newspaper clippings accompanying Gertrude Hoppock's affidavit. (See Exhibit A to the affidavit of Enid Pooley and Exhibits A and B to the affidavit of Marjorie McKillop.) They show that civilian America also regarded them as being in the Army. The testimonies confirm that officers and other enlisted men continually treated them as if they were in the Army.

Those officers, having immediate responsibility for the Signal Corps women, have all evidenced their support for recognition for the military service of these women. Captain Wessen's feelings are clear from his letter (attachment 4).

Attachment 8 to this statement is an affidavit signed by Colonel Edward M. Stannard, who had immediate responsibility for the telephone operating units in France. This affidavit was signed in 1954, shortly before Colonel Stannard's death. He is unequivocal in his support for recognition for these women.

Captain Roy Coles, who was also in the direct chain of command over the telephone operating units, likewise supported recognition of the military service, even while he was still in the Army.

In 1920, when he was attached to Second Corps Headquarters, he wrote many letters, such as that marked as Exhibits Y and Z to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock, to state bonus boards supporting state bonuses for the Signal Corps women.

Because he was still an active member of the Army, regulations precluded him from publicly supporting a position contrary to that the Array took at the time.

Thus the men under whom these women served supported efforts to recognize their military status.

The affidavits also clarify that the women of the telephone operating units understood that many female civilian employees worked under contract for the Army in France.

They refer in their affidavits to contract Quartermaster and Ordnance Corps civilian clerks. They insist that they viewed themselves and were treated as having military status. At the same time, all recognized the clerks to be civilians.

Adele Hoppock, in Special Orders No. 224 dated 12 August 1919, was authorized to wear a Victory medal and one Defensive Sector Clasp for her participation in the Meuse-Argonne offensive (see Exhibit K to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock).

Later, after the women returned home, as indicated in the affidavit of Merle Anderson, authority for the Signal Corps women to wear the Victory medal was rescinded.

In another special order, No. 231, dated 19 August 1919, in paragraph 45 (Exhibit L to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock), Adele Hoppock was relieved of duty in France in the following language: "The following named telephone operators, whose services are no longer required in the AEF, are relieved from further duty at this base, and will proceed by first available Government transportation to the United States. Travel directed is necessary concerning the military service." This is the same language used in paragraph 44 to relieve an Army Captain from further duty.

And the discharge letter issued to Enid Mack on 19 December 1918 (Exhibit C to the affidavit of Enid Pooley) again gives no clue as to the contract status of the telephone operators.

Exhibit U to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock is an American Legion bulletin, Seattle, 1920, showing that Signal Corps Telephone Operators were eligible for membership in the Legion.

Exhibit V to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock is Adele Hoppock's membership card in The American Legion for 1920. The American Legion accepted many other women of the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units into their organization.

For example, see the affidavit of Oleda Christides. Adele Hoppock was also a member of the Signal Corps Veterans Association of the War of 1917, as is evidenced by Exhibit W to the affidavit of Gertrude Hoppock.

Olive Shaw was issued war risk insurance (Exhibit B to her affidavit) and later, upon returning home, was admitted to a veterans' hospital for treatment (affidavit of Olive Shaw).

It is evident beyond question that Signal Corps telephone operators were treated in every critical respect as if they were members of the Army. The information which I have presented here, I believe, is conclusive proof as to their treatment.

All the Army has ever pointed to in opposition to recognition for these women is the Army's intention, as evidenced in the memoranda of November 1917. The Army has never offered anything in rebuttal to the evidence presented in my statement about the treatment of these women.

There is no question from a legal standpoint that the Army, by treating the Signal Corps women as if they were members of the Military, actually made them members of the Military, regardless of whatever intention was evidenced in the memoranda of November 1917.

A similar group of World War I veterans, faced with the same opposition by the Army, finally took their case to the courts. In 1971, by treating them in all critical aspects as if they were in the Military, they prevailed on their contention that the Army had made them members of the Military. This fully entitled to their Honorable Discharges. These were the men of the Russian Railway Service Corps.

The Corps was recruited to supervise the operation and upgrading of the Trans-Siberian Railway. The volunteers, all with extensive knowledge and experience in various aspects of cold-weather railroad operations, were given commissions in the Corps under the authority of the President of the United States.

They were issued uniforms similar to (and later identical to) Army officers' uniforms. They were furnished with distinctive insignia, including that worn by the Army Corps of Engineers.

From time to time, Corps personnel were issued Army weapons. They were paid at a somewhat higher rate than Army officers of the same grade and were not offered war risk insurance.

The Corps' members served with distinction in Siberia, Manchuria, China, and Korea until 1920, when they were ordered home and resigned their commissions. The full facts are set forth in Hoskin v. Resor, 324 F. Supp. 271 (DDC, 1971).

In 1971, after many futile attempts to have their faithful service voluntarily recognized by the Army or legislatively recognized by Congress, the President of the Associated Veterans of the Russian Railway Service Corps, on behalf of himself and the members of the Corps, brought an action against the Secretary of the Army for a judgment declaring that the members of the Corps were members of the United States Army during the First World War, and were thus entitled to an honorable discharge from the Army.

A judgment declaring the members of the Corps to have been members of the United States Army and thus entitled to honorable discharges was granted by Judge Gasch of the United States District Court, District of Columbia, on 23 March. 1971.

The Army appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The Court of Appeals affirmed the lower Court's decision in an unreported memorandum opinion on 24 January. 1973. Copies of both the District Court and Circuit Court opinions are attached to my statement (attachment 9 and attachment 10, respectively).

The Salient Facts

The salient facts on which the District Court quickly decided that the members of the Corps were entitled to recognition as members of the Army were as follows:

1. Members of the Corps wore regulation Army officers' uniforms and insignia and were issued Army weapons. The Court noted that the wearing of such uniforms and insignia by nonmilitary personnel is prohibited by law (10 USC § 771, 324 F. Supp. at 273).

2. Members of the Corps were serving under commissions authorized by the United States President and issued by the Army's Adjutant General. Under a special war power, the Court noted that the President was authorized to raise special and technical troops as he deemed necessary, 324 F. Supp., at 274.

3. The fact that the Corps' members were paid at a rate different from other Army officers was deemed insignificant by the Court because of well-known pay differentials for different types of Army service, 324 F. Supp., at 274-275.

4. The fact that Corps members were not offered war risk insurance did not trouble the Court (324 F. Supp. at 275).

5. The Court considered an administrative opinion of the Judge Advocate General that as similar to the men were civilians, but chose to disregard it (324 F. Supp. at 270).

The battle of the Corps members, however, was exceedingly costly. Members estimate legal expenses at $50,000 (attachment 11 from the Seattle Times. 19 February 1974).

The parallels between the treatment of the Russian Railway Service Corps members and the Signal Corps telephone operators are remarkably similar.

The Situation of the Signal Corps Telephone Operators Is Unique

Over the years, many groups who served as civilians in France during the First World War have petitioned Congress to change their status by legislation.

They argue that their service was of such caliber that they deserve a change in status. This argument proceeds from the basis that their status was initially civilian.

However, the Signal Corps telephone operators do not fall in that category since they do not concede that their actual status was anything but Military. This is due to the manner of enlistment and treatment after that.

Their service was exemplary and lavishly praised, but this is not the basis of their claim, and it is not this fact which sets them apart from all other groups.

No other group I am aware of has ever come forth with the type of evidence which the Signals Corps women can present, except the Russian Railway Service Corps, whose military status was judicially recognized.

I doubt that any group ever will, but each case must stand on its own merits. If some other group can demonstrate its entitlement to recognition, such as that proven by the evidence put forth by the Signal Corps women, then logic would dictate that they, too, must be heard.

But it is a flawed argument indeed to deny an entitled group of women their long-deserved military recognition simply because some other unidentified group might someday decide to make a similar claim for recognition.

The Signal Corps women have learned the bitter lesson that they must stand and be judged on their own merits. On a broader front, including other groups of women who served in France in World War II, Previous Legislation was doomed to failure in the 1930s and 1950s, as evidence by the letter of Captain Wessen, which is attached hereto, and the affidavit of Merle Anderson.

Served with Distinction in France

One Cannot deny That the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units Served with Distinction in France.

Signal Corps telephone operators received lavish praise for their service. Miss Grace D. Banker was awarded the Distinguished Service Order ln GO 70, WD.. 2 May 1919.

Her citation reads as follows: "Miss Grace D. Banker, Signal Corps, United States Army. For exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services. She served with exceptional ability as the chief operator in the Signal Corps exchange at General Headquarters, American Expeditionary Forces, and later in a similar capacity at 1st Army Headquarters. By untiring devotion to her exacting duties under trying conditions, she did much to assure the success of the telephone service during the operations of the 1st Army against the St. Mihiel Salient and to the north of Verdun."

I have attached a copy of this General Order to my statement (attachment 12). You will note that Miss Banker is not identified as a civilian but as Signal Corps, United States Army.

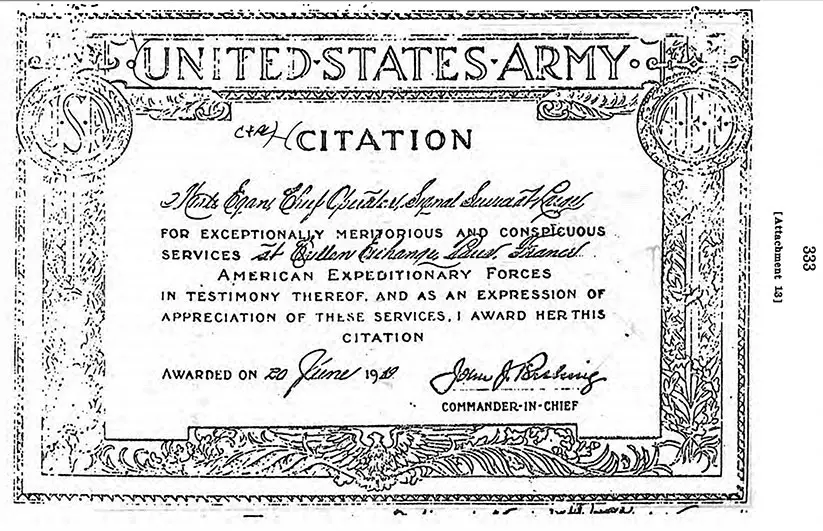

Many women, including Merle Egan Anderson, received citations for their services. I have attached a copy of Merle Anderson's citation to this statement (attachment 13 below).

Attachment 13: United States Army Citation, Merle Egan, Chief Operator, Signal [illegible] for Exceptionally Meritorious and Conspicuous Services at Crillon Exchange, Paris France. American Expeditionary Forces in Testimony Thereof, and as an Expression of Appreciation of These Services, I Award Her This Citation. Awarded on 20 June 1919 by John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief. Recognition for Purposes of VA Benefits, 1977. GGA Image ID # 19a5972db3

The official commendation of Brigadier General Russel, Chief Signal Officer of the American Expeditionary Force, is attached to the affidavit of Louise Maxwell as Exhibit D.

In his book, My Experiences in The World War, General John J. Pershing stated as follows: "One of the crying needs, when we once began using our telephone lines, was for experienced operators. Instead of trying to train men of the Signal Corps, I requested that a number of experienced telephone girls, who could speak French, be sent over. Eventually, we had about 200 girls on this duty.

No civil telephone service that ever came under my observation excelled with perfection as ours after it was well established. The telephone girls in the AEF took great pains and pride in their work and did it with satisfaction to all." Page 175.

Indeed, no one, including the Army, has ever questioned the excellence of the service rendered by the women of the Signal Corps Telephone Operating Units.

Signal Corps Telephone Operators Unit 7

Finally, it should be noted that 109 Signal Corps telephone operators had completed their training, were organized into the 7th Unit of Telephone Operators, and were in Hoboken, New Jersey, preparing to sail for France when the war ended.

Many of these women had been held in the United States for several months because the requirements of the AEF changed during the year 1918. Many of the women in the 7th Unit were highly fluent in French but had had no experience as telephone operators.

As the American telephone exchanges grew in France, which supported the American Expeditionary Forces, there was less need for fluent French operators and more demand for experienced telephone operators, so that many of the operators who spoke fluent French were passed over for those more experienced in telephone switchboard operation which the Signal Corps took in the units which preceded the 7th Unit.

Thus, through the fortunes of war, many women in the 7th Unit had been in the service as long as or longer than many of the women who eventually reached France.

These women of the 7th Unit were sworn in and similarly treated in all essential aspects to those of the earlier units, as witnessed in the affidavit of Enid M. Pooley. Consequently, there is no logical reason why benefits should be excluded for these women.

Conclusion

Signal Corps telephone operators were soldiers in every critical respect, considered themselves as such, and were treated as such by their officers and the American public.

It is a cruel injustice that 58 years after their honorable and exemplary service, the handful of survivors of the operating units must continue to seek their recognition rightfully.

The country owes these women formal recognition of their service as members of the United States Army, which is a small reward for the service they performed. It is time the debt is paid.

Thank you again for the opportunity to make this statement.

25 May 1977.

Attachements

- [Attachment 1]: 1918 Operator Still Seeks Justice After 50 Years - 1975

- [Attachment 2]: Women in the Armed Forces - 1952

- [Attachment 3]: Telephone Operators Creation Within Signal Corps - 1917

- [Attachment 4]: Ernest J. Wessen Letter - 1950

- [Attachment 5]: Status of Telephone Operators - 1918

- [Attachment 6]: Report on S. 2240 Relief of Women Who Served in the AEF - 1932

- [Attachment 7]: Military Telephone Regulations - 1918

- [Attachment 8]: Affidavit of Edward Mervin Stannard - 1953

- [Attachment 9]: Russian Railway Service Veterans v Stanley Resor, Secretary of the Army - 1971

- [Attachment 10]: Harry Hoskin, et al. V. Stanley Resor, Secretary of the Army, appellant - 1972

- [Attachment 11]: After 53 Years, He's 'Honorable' - 1974

- [Attachment 12]: Excerpt from General Orders No. 70, 26 May 1969

Mark M. Hough, Esq. "Appendix B: Prepared Statement of Mark M. Hough," in Hearing before the Committee on Venteran's Affairs, United States Senate, Ninety-Fifth Congress, First Session on S. 247, S. 1414, S. 129, and Related Bills, Washington DC: US Government Print Office, 25 May 1977, pp. 303-309.