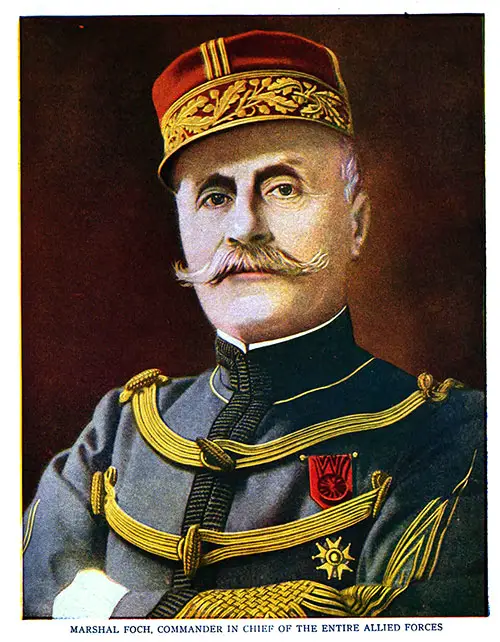

Ferdinand Foch, Commander-In-Chief of The Allies

Marshal Foch, Commander in Chief of the Entire Allied Forces. Pictorial History of the World's Greatest War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18bdcb6644

Napoleon, the First master tactician and fearless gambler with fate, once made a very shrewd remark. It was:

“In warfare men are nothing; a man is everything. It was not the Roman army that conquered Gaul, but Cæsar. It was not the Carthaginians that made armies of the Republic tremble at the very gates of Rome, but Hannibal; it was not the Macedonian army which marched to the Indus, but Alexander; it was not the French army that carried war to the Weser and the Inn, but Turenne; it was not the Prussian army that defended Prussia during seven years against the ten greatest Powers of Europe, but Frederick the Great.”

This maxim was seen to be as true to-day as in Napoleon’s time, when, after four years of furious fighting, great losses, and serious sacrifices, the Allies turned to Ferdinand Foch as their leader, and accepted the French General as their Chief.

Foch was born at Tarbes, near the Pyrenees Mountains on October 2d, 1851. Thus, he was sixty-six and a half years of age when he came to be selected as the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied forces.

His father, of good old French stock and a very modest fortune, was a provincial officer whose position was similar to that of a Secretary of State of one of the many United States.

Tarbes was the capital of the department of France called the Department of the Upper Pyrenees. The mother of the great soldier was named Sophie Dupré, and she was born at Argelès, some twenty miles south of Tarbes, near the borderland of Spain.

Napoleon the First was accustomed to reward those who fought and worked for him, and had, consequently, made the father of Ferdinand Foch a chevalier of the Empire.

This was because of his ardent aid in the war with Spain, or Peninsular War, in which the French were eventually well trounced.

However, the young Ferdinand Foch had a great passion for the Emperor, even from his earliest years, and we learn that, when a small boy, he would frequently get his father to relate to him the story of the career of the brilliant Corsican, sometimes called Napoleon the Great.

Tarbes is a very ancient city and now has some thirty thousand inhabitants, but when Ferdinand Foch was a little boy it had less than fifteen thousand men and women.

Under the Romans, Tarbes was a prominent city of Gaul, yet nothing of particular importance happened here in those ancient times, and not until after the battle of Poitiers in 732 — when the Saracens fell back after the defeat by Charles Martel — was there any disturbance at, or near, this peaceful town.

At this particular time, a valiant and venturesome priest called Massolin, hastily assembled many of the men who lived in the vicinity, and, with their assistance, he gave the retreating Saracens a good drubbing — the battle lasting for full three days.

At the end of this time, the retreating Saracens disappeared across the Pyrenees in a cloud of dust, leaving many an invader behind to enrich the soil of this farmland, which is now called the Heath of the Moors.

Forty years of peace now rolled past, and then again, the clarion notes of the war-bugle sounded across the green Fields, as Charlemagne the Great rode past with his twelve faithful Knights on their way to Spain to fight the Moors.

But the men of dark complexions were more of a nut to crack than the great Charlemagne had expected, and, after numerous skirmishes and battles, the German invaders were defeated: haggard, war-worn, and dispirited, they fled across the Pyrenees, followed by the exultant Moors with derisive shouts of defiance.

Marshal Foch. This Is the Man Whose Tremendous Thrust Routed the Prussian Guard at the Battle of the Marne. Launched at Exactly the Right Moment It Went Through the Guard "as a Knife Goes Through Cheese." Routed the Whole Army of Hausen, and Earned for Foch, Joffre's Verbal Decoration as " the First Strategist in Lurope." a Few Weeks Later, Through His Generalship and the Help of the Flower of the British Army, Foch's Troops Won the Terrible Struggle That We Call Ypres. Here Is a Legend That This Time He Won Commendation From Lord Roberts Who, After Studying His Plans, Is Said to Have Remarked to Officers of His Staff, " You Have a Great General." His Appointment as Generalissimo of the Allied Forces Marked the Beginning of Their Final Forward Drive to Victory. History of the World War, Volume 1, 1917. GGA Image ID # 18de195e2d

Over the mountains they went, and there — high up amongst the clouds — almost ten thousand feet in the air, is the Breach of Roland, named after a wild young French knight who, unable to cross because of his enemies, cut his way through a chasm some two hundred feet wide, three hundred and thirty feet deep, and one hundred and sixty-five feet long.

Across this dashed the intrepid warrior, and, spurring his horse, he leaped to the French side of the chasm, leaving the impress of the iron-shod foot of his charger in a rock. Here it can be seen today by you should you but go there and be in sufficiently good training to make the climb.

On the field of the Moors at Tarbes is a monument to valiant Massolin, and near the pass to the mountains is a bronze image of Roland the Impetuous: more famous in death than in life, and an ideal of valor for the chivalrous youths of France.

With these two monuments nearby grew up young Foch, and, with the traditions of his fighting ancestors dinned into his ears by many a town scribe, do you wonder that he breathed of battles when even a small boy, and that he was impregnated with the ideals of chivalry.

Young Ferdinand learned early to ride the spirited horses in the vicinity and is now an ardent and intrepid horseman.

He had one sister and two brothers, and they were most piously reared. At the college of Tarbes the future Marshal began his training, and this was in a venerable building, over the portal of which was the following inscription in Latin:

“May this house remain standing until the ant has drunk all the waves of the sea and the tortoise has crawled round the world.”

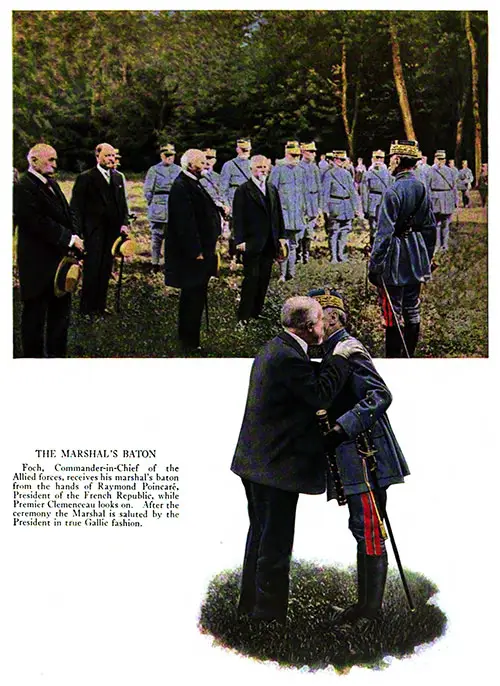

The Marshal’s Baton. Foch, Commander-in-chief of the Allied Forces, Receives His Marshal’s Baton from the Hands of Raymond Poincaré, President of the French Republic, While Premier Clemenceau Looks On. After the Ceremony, the Marshal Is Saluted by the President in True Gallic Fashion. History of the World War, Vol. 4: America and Russia, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18de43c112

Here the young French lad learned to read and write, and here he became conspicuous for his earnestness and diligence. At twelve years of age, his professor of mathematics thought so highly of him that he remarked: “He has the stuff of a polytechnician,” and about this time he read a history of Napoleon, in Thiers’ “History of the Consulate and the Empire.”

Fired by the glowing description of this prominent Frenchman, he determined to himself to endeavor to merit the praise of his countrymen, should the opportunity ever present itself.

About the year 1866 the family of the General moved from the ancient and historic Tarbes to Rodez — almost two hundred miles northeast of the pleasant town of his birth.

Here the father of the Marshal was appointed paymaster of the Treasury, and here the young Ferdinand continued his studies, and, later, when they emigrated to the city of Lyons, he entered the college of St. Etienne.

In 1869 the great soldier went to the Jesuit College of Saint Clement at Metz, where he was given the grand prize for scholarship by unanimous vote of his fellow students.

He had been here but a year when the Franco-Prussian war began, and, with true patriotism, the youthful Frenchman enlisted for the duration of hostilities.

Joining the Fourth Regiment of Infantry, he was sent to Chalon-sur-Saône, and, after the capitulation of Paris, was here discharged, in January 1871. He had not distinguished himself.

True, young Ferdinand had not distinguished himself, but he had learned one great lesson, and this was: LEARN TO BE PREPARED! GERMANY WILL STRIKE AGAIN!

He could not do anything at this time to save France from humiliation, but he determined to help France so that she should not again suffer such distress.

At Nancy, where the young soldier now was billeted, a big, fat German General called Manteufel had his Headquarters, and here he delighted in taunting the conquered French, by having his military bands play “The Retreat.”

The French hung their heads in shame, but young Ferdinand Foch hung his head, listened in distress, and took his examinations for the School of War, irrespective of what these bold invaders and conquerors were doing;

The undiplomatic Manteuffel finally went away jeering, and forty-two years later, a new commandant came to Nancy to there take control of the Twentieth Army Corps, whose position here — guarding; the Eastern frontier — was considered to be the most important to the safety of the nation.

Now, what did this new commandant do?

He immediately ordered out the hand of all six regiments quartered in the town and said to the bandmasters:

‘‘Fill the town with the strains of the 'Marche Lorraine' and the 'Sambre et Meuse'; we want to drown out the unpleasant memories of other days.”

This was on Saturday. August 23, 1913, and Nancy will never forget those airs. Soon the German guns were booming on the Nancy line, and the French were defending that town again against assault: this time to be unsuccessful.

The commandant who had ordered these bands to play was no other than Ferdinand Foch. He was getting even with the Boche.

Entering the School Polytechnic, Foch there distinguished himself by diligence and aptitude for his tasks.

There were many young men, and among them one Jacques Joseph Cesaire Joffre who was to distinguish himself later at the battle of the Marne.

Joffre graduated in 1872 and went to the School of Applied Artillery at Fontainebleau. Foch left the Polytechnic about six months after the great Joffre had graduated, and also went to Fontainebleau for the same training that Joffre was taking.

Both were tremendously in earnest and were hard workers. Young Ferdinand graduated third in his class and, departing immediately for Saumur, there learned not only how to direct cavalry operations, but also how to handle men. In 1878 he went to the Tenth Regiment of Artillery at Rennes as Captain, and there he remained for seven years.

The career of the great General from now on was characteristically methodical and according to rule. After remaining at Rennes for a full tour of duty, he was moved to Montpellier for a four years’ stay.

Raised to the rank of a Staff Officer, he was next transferred to Paris, in February 1891, as a Major on the general army staff. About the time that Marshal Joffre went to the Soudan, in order to build a railway in the Sahara Desert, Foch went to Vincennes as commander of the mounted group of the Thirteenth Artillery.

On the 31st of October 1895, he was made Associate Professor of Military History, Strategy, and Applied Tactics at the Superior School of War.

He was now forty-five years of age and was rated as a very competent officer. He was soon to make a wonderful reputation as a great teacher.

At the School the future Marshal made the men who sat under him love their work for the work’s sake and not for the rewards which they hoped to obtain.

He fired their brains with a love and ardor for the military art which made them feel that, in all of life there is nothing more worth the doing, or so worthwhile, as the knowledge of how to defend one’s country when she needs to be defended.

A French officer says of him:

“Many hundreds of Officers — the very élite of the General Staffs of the army — followed his teaching and were imbued with his lofty spirit; and, as they practically all, at the beginning of the war, occupied high positions of command, one may estimate as he can the profound and far-reaching influence of this one grand spirit.”

In times of peace he gave his students an enthusiasm for preparedness, when the cry, on all sides, was for disarmament and return to more peaceful attitudes.

At the beginning of his celebrated course of lectures on tactics, he always admonished his scholars with the words:

“You will be called on later to be the brain of an army. So I say to you to-day: Learn to think.”

In his opinion, an able officer is one who can take a general command to get his men to such and such a place, and to accomplish such and such a thing, and so to interpret the command to his men that each and every one of them will, while acting in strict obedience to the orders, use the largest amount of personal intelligence in accomplishing that which he has been told to do.

So, with word and pen, the mighty Foch labored with his students, knowing of the German menace, knowing of the German power, and, with full knowledge of their great masses of troops which could be moved by the nod of the Kaiser.

Zealously he labored so that when Germany should make her next assault on France his own country might be equipped with hundreds of officers who would know of Germany’s weak points of attack and would be prepared to turn her rashness into defeat.

When the war broke out and the hordes of gray-clad Germans swarmed across the Belgian border to crush their little state and rush upon Paris, the brilliant French leader was at Nancy, in command of the famous 20th Army Corps.

As the news was flashed that the Boche was at length advancing, he remarked: “Well, let us go to meet them as we have so often planned to do. Use, in fact, plan number forty-one.”

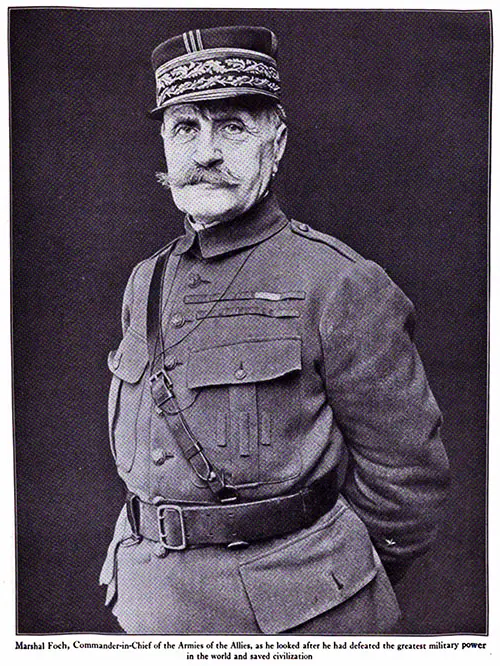

Marshal Foch, Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the Allies, As He Looked After He Hand Defeated the Greatest Military Power in the World and Saved Civilization. The United States in the Great War, 1919. GGA Image ID # 18dea07eaf

It is said that, at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian war, in 1870, the great Field Marshal von Aloltke — Chief of the German Staff — remarked, when he learned that war had been declared, “Use plan number seven,” and then tucked a paper away in a certain pigeon-hole on his desk.

In other words, for years the German staff had been planning numerous methods of entering France — upon the declaration of war — and the advance of the French toward Sedan made it necessary to use plan number seven.

But now there was a man upon the French staff who was as keen, as intellectual, as mathematical as General von Aloltke. He had worked out — years before — schemes for meeting the invasion of the country by the Germans; expecting them to come across the French frontier and not through Belgium, as they themselves had planned.

But the Germans considered their treaty obligations to Belgium to be "but a scrap of paper" — and thus — when the great army of invasion came crashing down towards Paris from the Belgian border, it was Foch who had to use, not plan number twenty, but plan number forty-one.

Then little five-foot-six-inch Ferdinand Foch first came into touch with his British Allies, a great crisis faced their lines, for, at Arras, the line held by the French General Pétain had nearly been pierced by the Huns.

The Belgians held a part of the front and they were suffering over two thousand casualties a day. They were also in momentary peril of yielding the defense of the Yser.

At Ypres the British had no reserves, and cooks and orderlies were holding off the swarming mass of Germans, thirsting for their blood and longing to got to the coastline. It was a moment of gloom and despondency.

At this juncture Foch came up, buoyant and cheerful. He had men with him, and he put them into earthworks, for it was impossible to dig trenches in the low, wet ground.

He planted his 75’s behind whatever cover he could find, and, delivering two fierce counter-attacks, the Huns decided to give up any further advance in that sector. Foch had won the day.

One British admirer said of him, “The little man would be cheerful and hopeful even if he had a bullet through his middle,” and, when he said this, he hit upon the true note of Foch’s character.

Hopefulness is an article of the General’s religion, for, “depression is a confession of intellectual weakness,” he has often remarked.

“Depression has lost more battles than any other cause,” he has also said. “To be gloomy is to admit that matter has conquered spirit.” The general, in fact, lives and flourishes by virtue of mental pluck.

“The soldier can snatch victory from the arms of defeat,” he has often remarked, “just as the coming of much needed reinforcements will do the same.” “intellectual energy can produce absolute forgetfulness of bodily ailments until the body is in actual danger of collapse,” is likewise one of his favorite maxims. In other words, keep on moving, never worry about your aches or your pains, but keep on moving and you will have your reward.

“Watch for depression in the enemy,” is one of his maxims. “Never watch for depression in yourself.”

Foch is thoroughly of a Gallic turn of mind: that is, he is vivacious and imaginative. He is a pure type of the Frenchman or the Gaul, whom Cæsar fought, and who has been characterized as of an indomitable spirit and ready for any emergency.”

He is as pure a type of his nation as General Pershing is of the United States, or General Haig of Scotland; a lean, quick- gestured, intellectual, aggressive “ priest of offensive warfare.”

He moves alertly upon his feet, and is, according to his friends, seen at his best when mounted upon his favorite horse, for then he looks much more than his five-feet-six-inches of height and much less than his sixty-six years.

While professor at the French Military School, General Foch wrote two books upon military matters: one, the “Conduct of War”; the other, the “Principles of War,” both of which are filled with maxims and arguments which might have been inspired by the present crisis.

One of his favorite maxims is this: “Victory is a thing of the will,” and the first essential in a general should be "moral and physical character and a possession of sufficient energy to take the necessary risks."

He says, at every opportunity, that the essential duty of a leader is to read the enemy’s mind, to outguess your opponent, as it were, and to hit where he least expects you to hit.

This principle he carried out in smashing the Germans after their advance towards Paris in the early part of the summer of 1918, and so successful was he in crushing the Boche that victory perched upon the banner of the Allies, and the proud hosts from Hun-land were humbled to the dust.

But let us look back a bit in history and see who was the real winner of the first battle of the Marne.

The vast German army, trained to the minute, eager for the capture of Paris, keen for another repetition of the triumph of the year 1870, had crashed through Belgium in the fall of 1914, had leveled the stout defenses of Liege, had beaten to a pulp the patriotic Belgian army, and bad pushed on upon a triumphant course towards Paris.

The British army, ninety thousand strong (but oh, what a ninety thousand!) was rapidly being brought, over the channel in order to hit the vast gray mass of invaders upon the right flank. Meanwhile, the French army — quickly mobilized — had marched on to meet this infernal machine and, if possible, to save the city of Paris from capture. Invader and defender met at the peaceful-moving waters of the Marne, in about the same place that Attila had fought the battle of Châlons, many, many centuries before.

There was a battle: intense, furious, awe-inspiring.

The Frenchmen said, “They shall not pass!” and, after one of the most sanguinary struggles in the history of the world, the German masses were stopped in their triumphant course towards the French capital.

“Who wrought the miracle of the victory at the Marne?” was asked of an old French artilleryman. “Tactically,” he answered, “the final victory was due to General Foch.”

“Ah, ha! And how was that pray?”

“General Foch saw a bad liaison between two German armies,” he explained. “There was a weak spot, although the attack was heavy on both the general’s wings. He thrust his guns up into the gap, while he developed the wedge with his infantry.

Those batteries, which were beautifully placed, raked the Germans so unmercifully that retreat was ordered.” “Only twice,” he added, “have I seen what they call a panic upon the field of battle.

This was the second occasion, and one large German unit, at least a battalion strong, cut and ran as the General’s 75’s opened on them from only a four- hundred-yard range. It was sauve qui peut (save himself, he who can).”

The battle of the Marne was a French victory: the Germans withdrew and intrenched, and now occurred a four years’ struggle for the mastery of French soil Which finally has resulted in a glorious triumph for the Allies; but, as the old artilleryman has so aptly said, it was Foch and his 75’s that won the day at the great battle near the scene of Attila’s defeat so many years before.

After the terrible fight, the English came in numbers across the channel, and, facing the Huns from Ostend to the Somme—where they joined their right flank with the French left — began a stubborn and relentless fight against the bloodthirsty invaders of French and Belgian territory.

Then their force was augmented by the American Army, so that when General Foch was placed in supreme command of the Allies, he directed the efforts of a greater force than any one man had ever before been asked to lead in the history of the world.

Men who are educated and paid to fight and to kill usually have a steely and heartless glance: the mark of militarism. There was nothing kindly about the countenances of either Caesar or Napoleon.

Kitchener had the cold, clear eye of a golden eagle. You would, therefore, imagine that upon the face of Ferdinand Foch would be shown the mark of the man of blood and of iron. But such is not the case.

There is a certain gentleness upon the countenance of this generalissimo of the vast Allied army : a Latin smoothness and flexibility.

The French leader has the reputation for being very reserved and quite distant in his manner. His orders are given very briefly and, when busy with war and its works, he is a man of very few words.

He hardly ever makes addresses to the soldiers: in fact, they would like to have him exhort them more than he does. Every man has some bad habit, or there is a general fault about him, and it is said, to his detriment, in a land where smoking is often practiced to excess, and, at a time when there is more of it than ever before, Foch is one of the champions. He is never without a cigarette between his fingers, but generally this cigarette is allowed to go out.

And how about his strategy? It is true that, with the vast resources at his command, there could be but one outcome of the attack by his troops upon the western front, yet it took a man of keen mind to direct the Allied advance so that the vast Hun machine could be smashed. On July 18th, 1918, these attacks were commenced; on November the 11th, 1918, they ended in victory.

At the beginning of his offensive, the backs of the Allies were against the wall — the sea wall, which, if the Germans were to reach, would mean victory for the Huns.

It was important that the invaders should be kept from reaching the ocean; that they should be smashed back from the Somme River where they had concentrated.

Along the river Marne a dangerous wedge had been driven into the French line and this jutted towards Paris. This must be cleared away before a genuine offensive could be possible.

Foch’s plan was like Grant’s before the battle of the Wilderness, i.e., to keep on hammering, hammering until he exhausted his opponent. The Americans were now arriving in great numbers and were concentrated along the Toul front and from St. Mihiel, east and south. These forces were not expected to attack at once but were to drill and be trained for a final offensive.

The British, meanwhile, were making such smashing attacks on the north that the Germans were losing vast numbers of men. Their lines finally became very much weakened and an appeal to Austria was the result. Thus the lines to the northward were temporarily bolstered up.

Now the Huns (cheered on from the rear by a crazy-headed Kaiser, whose bombastic utterances sounded like the remarks of a wild man) made an attempt to take Paris. Putting in division after division, they pressed on from Rheims to Chateau-Thierry. pushing on before them the French Army. All was going well until the Americans were rushed into the fray.

They came up in motor trucks, and among them the U. S. Marines, “ first to fight ” in all of the affairs in which Uncle Sam is interested. The new troops — full of ginger and “pep’'—were lined up against the Germans, and then there was such a signal turn in the tide, and such a murderous reception, that the Germans to this day call our soldiers “teufelhunden," or devil dogs.

The Marne salient was soon eliminated, but there was still grimmer work for the Americans. Down beyond Verdun to St. Mihiel, and then to Pont-a-Mousson, and it was important that this, too, should be blotted out. To the Americans was given this task.

How they did this, how quickly, how speedily — all the world knows. The St. Mihiel salient was soon wiped out, thousands of prisoners were captured before they could escape to their own lines, and, pressing their advantage to the full, the troops under General Pershing now moved on through the Argonne forest to the Metz-Lille road.

The pass of the Grand Pre was soon taken, and, trusting to the Meuse River to protect its right flank, the first American Army gradually worked its way northward until the Metz-Lille road was under fire of its guns.

Now, Austria withdrew from the war, and the Austrian divisions which had been sent to this section as reinforcements were withdrawn. The Germans broke and the American commander was not slow to take advantage of the situation.

The fresh troops, buoyant and cheerful, went forward, nearer and nearer to the vital railway, and, although the Germans made serious attempts to stop the advance, they were driven behind the Meuse and Sedan was taken. Sedan was where the French forces, under Napoleon the Third, capitulated to the Germans in 1870. At Sedan the troops from America delivered the final blow at Germany.

Meanwhile, the French — operating west of the American forces — gave a wonderful example of cooperation. Held back for a short time by the defenses of the Oise-Serre angle, they finally broke through the German wall of steel and the Huns were forced into the open.

They were made to fall back along the Aisne and a real retreat began: a real retreat along the line from the Oise to the Meuse.

The British, at the same time, had been delivering fearful blows in Flanders.

They crossed the Scheldt, north of Valenciennes, pushed their lines well to the east along the line of the Conde-Mons canal, and approached Maubeuge. Everywhere German resistance gave way, and France was almost entirely cleared of German troops.

At this propitious moment, when everywhere the Allies were triumphant and Austria had collapsed entirely, the German government signed an armistice which did away with the fighting until peace terms could be decided upon. No wonder Marshal Foch was jubilant, for, when you realize what a position, he had been in early in the Fall of 1870 you can appreciate what the French patriot was thinking about. Let us view the scene of long ago!

It was in the year 1870, the time, the early Fall, when the russet leaves have just commenced to flutter to the ground.

Along a winding road of northern France which led from the ancient fortress of Sedan rolled an open carriage. Before it rode a guard of French lancers, with arms shining in the sunlight, and with pennants fluttering from their lance-heads. Behind it clattered officers in the uniform of Napoleonic France.

Further in the rear, and, with a look of sneering conquest on their faces, came steel-helmeted Prussian hussars, rank upon rank, and squadron after squadron. It was a moving spectacle.

In the carriage, guarded by all of these men-at-arms, sat Napoleon the Third, Emperor of the French. He was going to meet the King of Prussia at Château Bellevue, to surrender his sword and his crushed and beaten armies.

Upon his flabby face was written great physical suffering, while deep lines were furrowed in his cheeks, telling of a grievous illness which was fast bringing him to his grave. His mind was in no pleasant state, for he faced a conquering foe.

The humiliated Monarch entered the salon of a château, followed by the officers of his staff. There, the leaders of the Prussian host with which he had just been battling awaited him.

The German officers courteously arose as he entered and stood at attention — their stiffened right arms touching their helmets as is their courteous custom.

The King of Prussia remained seated, and, arrogantly gazing at the man whose honored guest he had been not long before, he said:

“I am dee-lighted to see you.”

Napoleon the Third was stooping over, bent with pain. Drawing his sword, he presented it to the Prussian, hilt to the fore.

“Sire,” he whimpered, “here is my sword.”

The Prussian leered at it.

"I take it,” said he.

Fondling it a moment, as if it were some bauble, he cried out, loudly:

“I give it back to you.”

The French officers drew deep breaths, for the tone of the speech had stung them to the quick. Their black eyes shone like diamonds.

Among them was a young fellow — almost a boy — and, as the Prussian Monarch growled out the stinging words, they cut the patriotic Frenchman to the quick. “He clearly meant, I’ll take care of you,” said he, to a fellow officer. “He is a dog.”

This youthful officer was the future Marshal Foch. And he never forgot the words of the Prussian King.

The sneering Prussian was the grandfather of William Hohenzollern, formerly Monarch of Germany.

Turn the reel, Father Time, we have another picture to show the spectators!

The Fall of 1918

It is Fall again in La Belle France: The Fall of 1918:

Amidst the debris of the roads in northern France play searchlights. Three limousines creep into the flash of the brilliant glare, and, as they approach, white flags are seen fluttering from their bodies. Inside are Germans— cross-looking Germans — they seek an armistice.

The trespassers upon the soil of France are met with courteous consideration.

French officers meet them, smile sweetly, enter their cars and guide them over the dark roads until Château Frankfort is reached. It is in the deep forest of Compiègne, and a stop is made here for the night.

The Germans snore loudly. They do not let defeat worry them.

The next day all motor to Senlis, where, in a railway car, sits the same officer who was at the capitulation of Sedan, now a grizzled man. He is Generalissimo- in-Chief of the Allied armies.

The Germans enter the car, hats in their hands, and he rises to meet them.

His voice is tense, calm, clear.

“What do you wish, gentlemen?”

“We have come, Marshal, in order to arrange the terms for an armistice,’’ said one of their number. “We accept President Wilson’s fourteen points. Germany is beaten.”

What was his reply?

We do not know what the gallant Field-Marshal said, but we imagine that it was something like this:

“The terms, gentlemen, will be severe, owing to the barbarous manner in which your people have waged this war. They are as follows:”

Then he read to them the program already agreed upon by the Allies, and no more crushing ultimatum had ever been delivered to a beaten power.

The keen-eyed Marshal had no tone of sneering or of overburdening triumph in his voice as he read. Yet — away back in his mind — he had the scene of another surrender indelibly engraved upon his memory — that of Sedan, when his Emperor was humiliated. And, as he read on, the great Generalissimo of the French and Allied armies, smiled — not leeringly, but good- naturedly — into the stolid eyes of the crestfallen German emissaries.

What had the Marshal to do with the final triumph?

This is well expressed by the words of Premier Clemenceau, who, when approached by several Senators with the words:

“You are the savior of France,” replied: “Gentlemen, I thank vou. I did not deserve the honor which you have done me. Let me tell you that I am proudest that you have associated my name with that of Marshal Foch, that great soldier, who, in the darkest hours, never doubted the destiny of his country. He has inspired everyone with courage, and we owe him an infinite debt.”

SO, THREE TIMES THREE FOR GENERAL FOCH!

He is the man who never lost his cheerfulness in spite of the fact that the soldiers of his country — bleeding and distressed — have been fighting a grueling war and struggling for a long time against terrific odds.

The signing of the armistice terms, submitted by the Allies, practically brought to an end the greatest war in the history of the human race — a war which brought suffering and misery to the people of every land: which cost $224,303,205,000 in treasure, and nearly 4,500,000 lives.

The end of hostilities 1,556 days after the first shot was fired, tendered to civilization the assurance that never again shall people be threatened with the slavery of a despotically autocratic rule.

Cheerful when things were blackest, cheerful when events were brightest, let history record with truthful significance, that here — at least — has been one soldier who is the living personification of that ancient doctrine:

“When things look darkest: SMILE! SMILE! SMILE!”

Charles H. L. Johnston, Famous Generals of the Great War Who Let the United States and Her Allies to a Glorious Victory, Boston: The Page Company, 1919, pp. 87-108.