Edouard De Curiéres De Castelnau - The Defender of Nancy

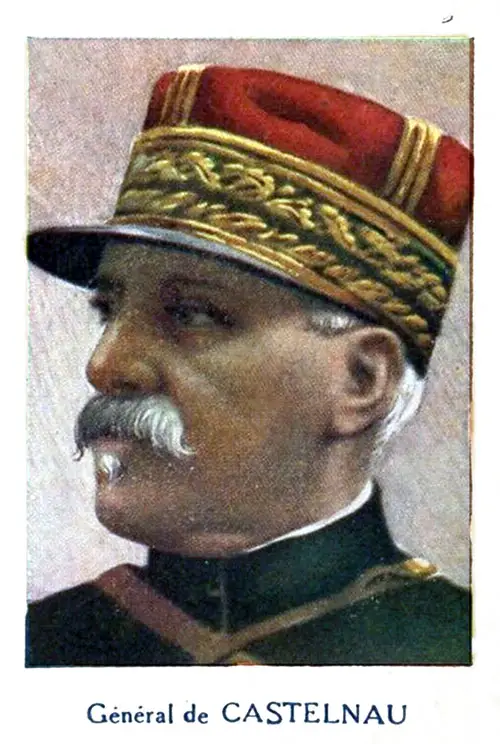

Général Edouard de Curiéres de Castelnau, nd. circa 1918. GGA Image ID # 18c01c2a1f

A French General — grizzled, troubled-looking, sad-eyed — was dictating dispatches to his Quartermaster near the battlelines at Verdun. Far away roared the great guns, and white wisps of smoke rolled across the pock-marked fields. Suddenly a mud bespattered officer appeared, and, saluting, stood at attention as the war-weary General looked him over.

“What is it, Piquard?” asked the General, still scribbling.

The officer had tears in his eyes and did not reply. Again the General queried:

“What is it?”

Now the officer had found his voice, but it was quavering, as he stammered:

“Your son Xavier has just been killed in Alsace. They say that he fell gloriously in a charge.”

The old soldier’s eyes glistened with tears and he remained silent. Then, turning to his Quartermaster, he remarked:

“Go on, sir. One cannot forestall the Will of God. His Will be done.”

Without more ado, this Spartan continued with his dispatches, and soon completed the work at hand. He was a Stoic — and a Philosopher. Yet deep, deep into his fatherly heart had pierced the Arrow of Sorrow.

This philosophical soldier of the French Republic was General de Castelnau, known all over France as the “Hero of the Grande Couronne de Nancy.”

A true veteran is the eminent soldier; a veteran not only of the Great World War which has just ended, but also a veteran of the war of 1870 between France and Prussia. General Curiéres de Castelnau, in fact, was born on December 24th, 1851, at Saint-Afrique, Aveyron. His father, a distinguished Avocat, or Lawyer, had left the family castle Saint-Come in order to settle in this little French town, where he married Mademoiselle Barthe, of Rouergne, whose ancestors had all been Notaries at Murasson, as well as Mayors of the sleepy little village.

In the Eighteenth-Century, Jean Baptiste de Curiéres, Baron of Castelnau, was a Page of the French King, and in the year 1750 he was made a Captain of Cavalry. In 1770 we find him a Lieutenant Colonel, a Brigadier in 1772, and a Marshal in 1788. He was a fighter, too, and was desperately wounded at Forbach, in recognition of which the King gave him a sword studded with jewels, which has been preserved as a precious relic by the de Castelnaus for many years.

This eminent soldier had three brothers, one of whom was an Abbey, another a Chevalier, and a third was distinguished as a Sea Captain. This fellow married his cousin Ayral du Bourg and had a son Jean Baptiste — historian — one of whose sons was the father of Michel de Castelnau, born at Espalion in 1810, who was the father of the General of the Great War.

The street where the now eminent soldier was born is on the edge of the River Sorge, and, although it formerly had the name of Bart, this has now been changed to the Street of General de Castelnau. This change was made on January 8th, 1916, and many speeches were made at the time, by the Mayor, and others, in praise of this gallant Frenchman who commanded the French Poilus at the awful battles around Verdun.

All of the de Castelnau brothers went to a Sanctuary of the St. Joseph Catholic Sisters, in the village of Bart, and it has been recorded that, although the two older brothers excelled in their lessons, the youngest of all — the Great de Castelnau — remained at the bottom of his class in every one of his studies.

In spite of this inability to be a student he was so full of fun that he was the life of every party. He was also of an inquisitive frame of mind and was one day discovered in the act of dissecting a mechanical horse in order to see what was in his stomach. In physical sports he was always first, and in military tactics also.

The French boys were accustomed to play a game called tournoi, or tournament, which was something similar to the game of Rounders. They also used to get up mock-plays, or fetes, called carrousels. One day the great Bishop of Founders — known also as the Monseigneur de Lalle, head of the Diocese of Nancy, came to the school, so a fete, or carrousel, was staged for his especial benefit, in which our future de Castel- killer-of-men took a very prominent role.

At the close of this affair there was a great parade of all who had taken part, and the future General, mounted in a Greek chariot, drawn by soldiers, was carried past the portly Bishop, whom he saluted by bowing low. The Prelate was much pleased by the performance, and especially by the work of little de Castelnau, so he said:

“Young man, I congratulate you. You have staged this affair quite excellently, and you yourself are to be highly commended for all that you have done to make my visit a happy one. I thank you, and may you continue to bring happiness to all.”

This was in the year 1867, quite a long time ago, you see, but the future General never forgot what the good Bishop had said to him.

Little de Castelnau remained for nine years in the College of St. Gabriel before he went to Paris and became a student at St. Cyr; the same Military School at which Napoleon the First was educated.

Here he remained only a few months and did not graduate. Instead he was dispatched to the Rhine on August 6th, 1870, and billeted with the 31st Infantry, which was soon engaged with the advancing Prussian army under Von Moltke and Bismarck. Six months after he had left St. Cyr, he was a Captain, and he was only nineteen years of age.

Throughout the fierce struggle between Napoleon the Third and the Prussians the eminent soldier fought with a courage that was most commendable, and, at the close of the campaign, he continued in the army, entering the College of War in 1878.

Since this time he has always been identified with the French army, and his career has been stable and ever upward.

- In 1889 he was a Commandant.

- In 1891 he was decorated.

- In 1900 he was made a Colonel.

- In 1909 he was created General of Brigade.

- In 1913 General, or “Papa,” Joffre called him to be Chief-of-Staff of the French Army.

He was soon sent to take charge of the Poilus in Lorraine and was made General-in-Chief of the Second Army, which valiantly withstood the shock of the superior German forces which were hurled upon bleeding France. The Army of Lorraine was held on the heights of the Grand Couronne de Nancy while “Papa” Joffre gave battle to the Germans on the Ourcq and the Marne.

The village of Nancy, shelled by the great German guns, stood in the path of the advancing Teutons, and, with all the might of their vast machine they here endeavored to crash through the French lines and on towards Paris. But they had General de Castelnau to contend with, and they had the Army of Lorraine, the ranks of which were filled with fathers of families, with brothers and relatives of all the women and children behind, who were clinging to their houses and farms, hoping against hope that this tide of invasion would be checked.

The French 75’s was limbered up and pointed at the Germans, and whenever the Hunnish masses endeavored to press onward over the hills of Nancy, they were met with such a withering fire from the belching light guns that they could never advance.

Finally, the French themselves went on, and General de Castelnau had the satisfaction of seeing the Hunnish forces beaten away from the town, while their long lines of artillery had to be withdrawn from the trenches of the Mortagne and the Meurthe to positions nearer their own frontier.

A great sigh of satisfaction went up from all the French behind the solid line, as this withdrawal occurred, but there was weeping and desolation in every home, for the very flower of France had fallen — among them the youngest son of our General, and also his favorite, the boy Xavier. The great soldier was the father of eight sons and four daughters.

Although the Battle of the Marne will go down to history as the great battle of this war, this battle of Nancy and of Lorraine was the most important of French victories, and it made possible the defeat of the Germans at the Marne. This Lorraine field was the field that France and Germany had planned — for a generation — to fight on. The French General Staff had prepared numerous plans of battle for this particular sector, as all knew that the Germans would enter France through the gap in between the Vosges mountains and the hills of the Meuse.

Had the Germans but respected the neutrality of Belgium, and not invaded the territory of King Albert, the entire army would have pressed into France by this route. The Marne battlefield was one reached by the Germans by chance. This field, however, was one upon which the French had always known that they would have to fight — every foot of this country had been thoroughly studied by the members of the French General Staff.

General de Castelnau had commanded an army whose line stretched from the village of Pont-a-Musson, on the north, to Bayon — southeast of this position. Barbed-wire entanglements were in front of all this sector, and in the woods of Bois de Fac the Germans reached the high-water mark of their invasion, a position similar to the Clump of Trees at Gettysburg. In the field below this wood now lie four thousand dead Germans; who they were no one knows; they came here at the command of their Kaiser, and they died here before the weltering fire of the French muskets and 75’s.

Straight across the river from here, and west of it, is the Forest of the Advance Guard, where were thousands of German machine-guns on the day of battle. Here the French, lying in their trenches, had been swept by an awful fire, but tenaciously and gamely they had held on. So frightful were their losses, however, that their commander had received an order to retreat.

He insisted that the order be put in writing so as to gain time, for he did not wish to fall back. The order finally came — made out by one of General de Castelnau’s aides. It had to be obeyed, so the French slowly and reluctantly retreated.

With silence and depression they went southward. Suddenly a cry resounded all along the line. It was: “The Germans are retreating, themselves.”

“En Avant!” With a cheer the French came back, reoccupied their old trenches, and fired at the backs of the enemy, — the northern door to Nancy had been blocked by the bodies of the Poilu.

Vet the Germans attempted to regain the lost ground and made a night attack. Not less than twenty thousand men — an entire Division — were formed beyond the French position and launched four times at the bleeding but gamey Poilus.

The slope which they advanced over was very gradual and these were picked troops, chosen to break through to Paris. But — they failed —failed so utterly that they called this the Hill of the Dead, and thousands of them now lie there, buried without any regard to either regiment or name.

The Grand Mont d’ Anna nee is on the southeastern corner of the Grand Couronne and is the most famous point of the Lorraine front.

From the top of this hill, one thousand and three hundred feet high, one can look eastward into German Lorraine, the Promised Land of France.

On the top of this hill General de Castelnau watched his own troops follow the Germans over the frontier in August. In the hills beyond the Germans had hidden their machine-guns, and, as the Poilus advanced exultantly, they had been unsupported by artillery, so had broken badly when enfiladed by the murderous German fire.

In the valley below, more than two hundred thousand men had fought for days and days. At one place a French brigade charged across the fields at 8:15 pm, and by 8:30 it had lost three thousand out of six thousand men.

Then the Germans, flushed with success, debouched from the woods to charge themselves, and in a quarter of an hour they lost three thousand five hundred soldiers. The land is simply one vast graveyard.

In the distance is the little Seille River, which marked the line of the old frontier. Across this first came the Germans, and across this they afterwards retreated, swarming across the low, hare hills, and disappearing into the woods — the Forest of Champenoux.

Here they rallied, turned, and fought a frightful battle with the exultant French, which lasted for days. The trees are hacked and torn to pieces with shell fire.

At the foot of the hill is a fountain, in the center of a cluster of buildings, and here is where the Germans reached their highest point of advance.

The houses were torn asunder, the whole place was badly wrecked by the battle, while just beyond was the line which Prince Bismark had drawn upon the soil of France as the boundary between France and Germany after the war of 1870, a line which had been a bleeding wound in the side of France ever since.

It is said, that, — as the attack was going on near the Forest of the Advance Guard, the Kaiser and a brilliant staff rode upon a hill near the river Seille to watch the progress of the battle, and to advance into Nancy at the head of his triumphant troops. Clad in white uniform and breastplate of mail, he was a thing of joy and beauty forever.

But there was to be no triumphant advance, instead a riotous retreat, with the disheveled legions cut up, butchered, and massacred by the French machine-gun and rifle fire.

The Kaiser had not guessed correctly — this was a far different France from the France which Prussia attacked in 1870.

The people of Nancy itself remained calm during all of this bitter fighting, for they had been expecting this very thing for many years.

The bakers still made macaroons and the children still went to school, in spite of air-raids by Taubes and Zeppelins. For forty-six years the population had lived before the German frontier expecting invasion at any moment and thus they were well prepared for just such happenings.

"Peace will come, but not until we have our ancient frontier," said the people. “We must have Metz and Strassburg again. We have waited a long, long time for revenge, and it must be ours.”

Yet — without the assistance of the United States, it looked as if that day of revenge were never to arrive.

It was the third week in August 1914, that the army of de Castelnau crossed the frontier of Alsace-Lorraine and entered upon German territory, and it was a joyful day for France when it was announced that the victorious armies had reached the villages of Sarrebourg and Morhange and were sitting upon the Strassburg-Metz railroad. Yet in Berlin there was gloom and depression, and no one there had any regard for the name of de Castelnau.

The French themselves thought so highly of their soldier that, on December 11th, 1915, he was made a Brigadier General, which gave him the position of Generalissimo, and shortly after this he was called by General Pétain to help save the Citadel of Verdun. This was in February 1916.

Of Pétain and Verdun, you know. You know how long and how strenuously the Germans under the Crown Prince endeavored to seize this stronghold, and you know how valorously the French fought.

To Pétain and Joffre have been given the honor of this stubborn resistance, but de Castelnau was also there, and he directed many a counterassault against the lines of the enemy.

Verdun is now a wreck — a pile of ashes — but if future generations are to place tablets to commemorate the gallant defenders of the citadels and forts they will do well to place the name of de Castelnau upon one of them, and to place it in a most conspicuous position.

So proud of their soldier have been the people of the town of Bart that they have wanted to replace the statue of Liberty there, chiseled by Bartholdi, with one of the brave hero of the Couronne de Nancy, but so far they have not done so. Perhaps this may yet happen.

On September 18th, 1917, a delegation of his townsfolk carried him a sword, and, after a poem had been read and an address had been made by the Mayor, it was presented to the aged hero; a veritable Chevalier Bavard, with a heart of steel and a soul of crystal.

The gleaming weapon was of the finest workmanship and was quite fit for a King. On the hilt was emblazoned a coat-of-arms of the General, with the inscription in Latin:

“Currens Post Gloriam Semper,” which means “Always Following After Glory.” This inscription was surrounded by a wreath of laurel, symbolic of the lives of the de Castelnaus.

A day or two before the armistice was signed, the prominent man of war was named to command a group of armies, known as the Army of the East, and he had made elaborate preparations to make a great attack between Strassburg and Metz. The armistice saved the Germans from sure defeat and annihilation.

The end of the Great World War finds General de Castelnau respected and loved by the Trench and shortly to be named Inspector of Armies. May the dosing years of the life of the Hero of the great battles in Lorraine be fraught with praise and honor, for the doughty general of the zealous Poilus had saved Civilization from the domination of the hard-fisted and ill- mannered Germans.

Charles H. L. Johnston, "Sir John French: The Man Who Led the First British Army," in Famous Generals of the Great War Who Let the United States and Her Allies to a Glorious Victory, Boston: The Page Company, 1919.