In the Grip of the "Flu" (Spanish Influenza) - 1920

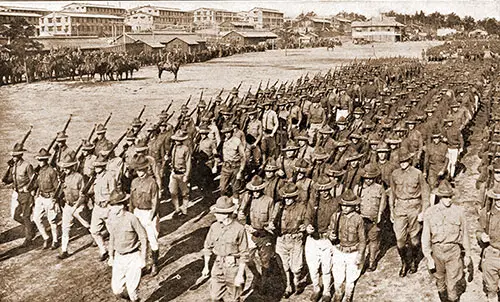

At Camp Devens, as soon as General McCain got his schools running properly and the men were "throwing their weight into the collar, " so to speak, a review of the division was ordered.

The Plymouth Division Passes in Review at Camp Devens. Photo by Leonard Small, Boston Globe. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 15034dd0fd

The general had seen all there was to see of the camp, and he had seen practically every man in it at various times. Now he wanted to see them all together. So the first review of the division was held on September 14, less than a month after it had been organized.

Hundreds of people came to Camp Devens to see that review. It was not yet believed that anything resembling soldiers could be made in so short a time, and the public had a very earnest desire to be shown.

Well, they were shown, and they went away wondering, for, as far as most lay people could see, this first review of the 12th Division didn't differ so very much from the last review of the 76th, except that there were more men in the latter, inasmuch as the 12th Artillery Brigade was training thousands of miles away from the Infantry Brigades.

The men marched and generally conducted themselves like veterans, thereby satisfying their officers and the commanding general, though the latter, when asked what he thought of the showing of his new command, replied that it was fine, but "wait until the next one and see the difference. "

It was just about this time that the Spanish influenza was fastening its grip on the camp. The epidemic started so gradually that few knew that it was upon us until it was raging.

On the day of the first review it was announced that there were 2,000 cases of the disease in camp, but as yet no deaths were reported. The day following; however, two deaths were announced.

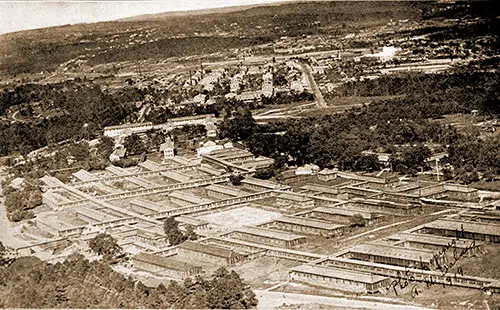

The Base Hospital with the Rest of Camp Devens in the Background. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1503b7770a

The next day there were 3,000 cases of it, and it was announced that four men had died in the past twenty-four hours. Twelve additional wards at the Base Hospital had to be taken over to accommodate the sick men, and it was thought that this was pretty bad!

On 19 September [1918], the town of Ayer was quarantined against the soldiers. This was not so much to protect the soldiers as to protect the civilians living near the camp, for civilian New England was having a hard time with the influenza, whereas the men in camp had the best possible medical attention.

In the cities and towns throughout New England the doctors were so busy that the services of a physician were hard to get, for the medical men were working day and night, with far more cases on their hands than they could find time to attend. And nurses were at a premium.

But still the number of cases in camp continued to grow. From 3,000 to 5,000 to 7,000, clear up until at one time there were more than 10,000 men being treated.

The Student Nurses at the Base Hospital, Camp Devens. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1502aa2783

Front row, left to right: Misses Nancy S. Hapgood, Edith I. Perkins, Harriet E. Scott, Luella A. Belcher, Helen N. Davies, Helen A. Kennedy, Mildred A. Prior, Marjorie E. Davies, Jennie M. Carter, Mabel A. Turner, Dorothy M. Israel, Worthington Harry, Doris Paine, Isabel B. Walker, Alice E. Stansbury

Back row, left right: Misses M. Ethel Smith, Natalie K. Robert, Virginia Wright, Annie A. Dennett, Rosalind G. Parker, Eleanor Rantoul, Rose McNaught, Jeanette Kilbam, Beatrice K. Barnes, Elsie I. Rogers, Louise E. Flaxington, Lucie E. Greenfield, Helen S. Grant, Candace F. Seeley, Dorothy W. Crosby, Helen K. Friend, Olivia Ames

And so the daily death report continued to grow larger and larger, from three, to five to twelve to fifteen to twenty and then to twenty-eight daily. Then New England began to be really alarmed at the situation at the cantonment.

But as a matter of fact the epidemic had about spent itself before the death list began to swell to such alarming proportions. At the time when the death list was highest there were fewer cases of influenza in the hospital than when the daily death report showed less than a dozen names.

The reason for this was that thousands of men were only in the hospital a few days, while most of those who succumbed to the disease were ill for several days before they reached the crisis.

But despite the frightful handicap imposed by the epidemic, the training of the division went on just the same. It had to. And the medical officers had decided that to continue the training was the best possible thing for the men. It kept them out in the open air—one of the surest preventives—and also distracted their attention from what was going on around them.

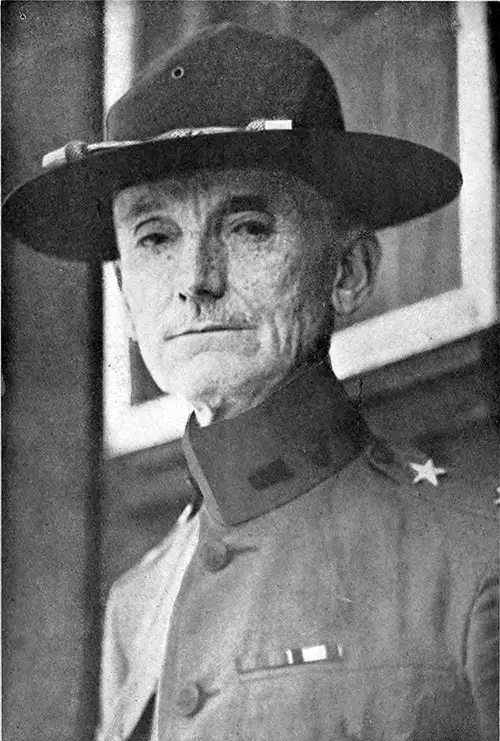

This policy unquestionably saved many lives. And, among other things, the influenza epidemic showed the men of the 12th Division the true caliber of their commanding general.

For he personally directed the fight against the plague, assisted and advised, of course, by Lieutenant-Colonel Condon C. McCornack, his division surgeon, and Lieutenant-Colonel Channing Frothingham of Boston, commander of the Base Hospital.

The general had these two officers worried. They were worried about the general himself, for he insisted on spending the greater part of the daylight hours at the hospitals, going around among the men, talking to them and cheering them up.

He scorned to wear a mask to protect himself. He was building spirit among the sick, spirit with which to fight this plague that seemed to sap the vitality from a man as no other disease did.

And so, calmly, cheerfully and kindly, he went his way through the hospital wards, among the dead and the dying, talking to these lads, asking them all the little personal, intimate questions one of their own would ask and seeing to it that they got everything that could possibly be given them.

Then, as night drew on, he went back to his office, on Headquarters Hill, where all through the day the work had been piling up, and there he worked far into the night, attending to the vast amount of detail attached to getting his division into shape to go to France.

He didn't have to spend this time in the hospital. There was no rule nor regulation that called upon him to do it. But he wanted to save every life that could possibly be saved, and he wanted to be sure that everything that could be done was being done, so he went himself to see about it.

Major General Henry P. McCain. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 150401ed1f

And he knew, too, that most of these men were going to get well, that when they recovered, they would remember that their general stuck by them when they were in a tight place and that they would be eager to do the same by him.

This is only one of the things that built for Major-General Henry P. McCain (Commander of the Plymouth [12th] Division,) the loyalty of every man under his command.

As September [1918] drew to a close the daily death toll grew. On September 23 there were 63 deaths, on September 24 there were 66, on the 25th there were 77, on the 26th there were 60, on the 27th there were 81, the highest daily death toll during the epidemic.

From that time on the daily death list decreased, 56, 45, 29, 30, 14, 17, 14, eight, and so on until the pre-epidemic average was reached, which was only one or two a week.

In all there were about 800 nurses, officers and men who succumbed to the epidemic, a low figure compared to the harvest of the grim reaper in other camps and in many civilian communities.

After days and nights of the bitterest kind of fighting, Camp Devens had won its first victory. The Spanish influenza was completely stamped out and Camp Devens was one of the cleanest and healthiest spots in New England.

It was a victory won with the sacrifices that attach to all real victories. From the time the epidemic broke out approximately 14,000 men were in hospital with influenza and pneumonia at Camp Devens. One out of every 18 of these cases died.

There were undoubtedly hundreds of cases of great sacrifice and devotion passed by unnoticed, except by a very few. But there are other cases of both women and men who did their duty and a lot besides that came to the attention of the authorities, and many of these went on record.

The whole battle to rid the camp of Spanish influenza is a story of never-ending toil, of sleepless days and nights, of heroic devotion to duty, of weary, heavy-lidded, dogged resistance against an unseen and practically unknown foe; of calm and patient women, working on sheer nerve, of brave but in experienced men, setting their hand to a task and struggling to absorb a knowledge of their work as they felt their way along, and of overworked physicians, fighting, fighting, fighting and never ceasing to fight until every single man had been attended.

It was a struggle, in which the members of the Army Medical Corps lived up to the best and highest traditions of the country.

The base hospital contained 1,800 beds when the epidemic descended upon it. At the height of the epidemic there were close to 10,000 patients and through it all the base hospital kept 1,000 beds ahead of the need.

When the epidemic started there were some 200 nurses, including the members of the Nurses' Training School, at the Base Hospital. Almost overnight there were more patients in the hospital than it would seem humanly possible for 200 nurses to take care of. They kept going, however, and every man was cared for before a single nurse rested.

There were enough doctors to care for any reasonable number of patients that might be expected to be in the hospital at one time. But when the deluge came the doctors showed themselves to be of the same stuff as did the nurses.

As the epidemic developed there was no such thing as enough nurses and doctors. The hospital used every last one that l could be procured, and still more were needed. But those who were on duty did the work of two and three, and somehow every patient was cared for.

As quickly as it could be secured, assistance was brought in from the outside. This help consisted of both military and civil. Army doctors and nurses were rushed from other camps and army posts.

Offers of help from civilian organizations all over New England began to come in, and many of them were accepted. Everyone who could help and who wanted to, came pretty near having a chance to make good. And most of them did.

Five girls who were serving their country at the Camp Devens Base Hospital made the supreme sacrifice; they contracted the disease they were fighting and died. They died the death of a soldier.

They stuck to their posts until the end, without a thought of themselves and with only their duty in mind. When the decline in the epidemic came there were 400 nurses at the hospital.

Two doctors gave their lives, also. One of them, Captain Charles A. Sturtevant of Manchester, New Hampshire, lost his life because he stuck to his post after he was ill himself.

That his work for his country was appreciated by his Government was evidenced by the fact that his promotion to the rank of major arrived at Camp Devens the day after he died. Lieutenant Thomas R. Ferguson of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, was the other doctor to succumb to the influenza.

It would be impossible to give individual credit everywhere it is due, because, from the highest officers right down to the lowliest private, every last man and woman in camp did his and her duty.

The men of the Sanitary Train were called upon to help, and Lieutenant-Colonel McCornack, the division surgeon, paid them high tribute for the manner in which they "went through."

Colonel McCornack had been at that time about eleven years in the service, and during that time he had fought just about every kind of disease there is to fight, including an epidemic of black smallpox in China.

And he knows service when he sees it. After the influenza epidemic had been conquered at Camp Devens, he told what he thought of these men:

We had to take men from the Sanitary Train and send them to the Base Hospital for duty. Most of these men were new to the service and they didn't know anything about hospital work.

They were told what they were up against. They knew that many of them were going to contract the disease and that some of them would die.

But when they knew that men were dying at the hospital because their help was needed, and when the order came to go up there for duty, not a man of them so much as looked back.

And some did contract the disease and some of them did die, but they knew that it was part of the army game and they did it willingly and gladly, like true soldiers. They are just as truly heroes as though their lives had been given on the battlefields of France.

Ordinarily there isn't any special credit due a man for doing his duty, but certainly a word of commendation and praise is due these boys who were green at the game, but who were willing to play it to the best of their ability.

Ambulance drivers, orderlies, nurses and doctors—the story is the same from beginning to end. Every last one in the service vindicated the faith placed in him by his country and by his commanding officers.

They showed the true spirit of America, that spirit before which nothing but the clear, bright flame of freedom and democracy can hope to stand.

The Red Cross lived up to its highest traditions also. They had a recreation building for convalescent Base Hospital patients right beside the hospital, and that building was turned over to the forces that were fighting the plague.

The Red Cross also supplied much medical material to the military authorities, and the workers were devoting themselves day and night to the sick men and to the relatives of those men who were hurrying toward Devens from almost every state in the Union.

The Knights of Columbus turned their Base Hospital building over to the military authorities for the housing of sick men and they devoted another building to the use of relatives of the men, housing them there during the crisis of their boys.

The Hostess House, which was early established at Camp Devens by the Young Women's Christian Association and was under the supervision of Miss Annette Griggs, became a large dormitory for the accommodation of people whose loved ones were facing the Hereafter up at the hospital, and the Hostess House also ran a motor bus to the hospital for the benefit of fathers and mothers of sick boys.

The Hostess House at Camp Devens. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1503705277

It was the same with the Y. M. C. A., as with all the rest of the welfare organizations. Their Base Hospital hut became a ward, and the secretaries devoted themselves to the sick and dying.

Perhaps no one worked any harder than did the chaplains. These big-hearted men practically lived in the wards, comforting the dying, writing letters for the men, guiding frantic parents through the lines of cots in the hospital, which filled even the corridors, and doing a thousand and one things to be of assistance.

For the chaplains in this army that we raised were general utility men, friends of the soldiers who could be called on for anything that might come up where an outside and disinterested party was necessary.

They did everything from performing marriage ceremonies to judging a Broncho-breaking contest, from writing musical comedies for the men to act to refereeing basketball and baseball games. There were no better loved men at Camp Devens than the "sky pilots. "

And perhaps right here may be mentioned what was considered by many one of the crowning achievements of one of these soldier parsons, though chronologically it is a little out of place in this narrative.

After their long battle with the influenza, on top of their intensive training, which was halted by the coming of peace, the regiments of the 12th Division vied with each other for supremacy in sports, drills, music, education, all kinds of contests, and finally in the matter of dramatics.

The writer of this story is not sufficiently versed in the fine points of drama and music to dare to name the leading regiment of the division in the histrionic field, but certainly no chronicle of the events at Camp Devens would be complete without mentioning the final big show of the 73d Infantry.

The 74th Infantry produced a revue in the fall of 1918 that created a sensation in camp. It was shown at the Liberty Theater, and was a huge success, as there was plenty of talent of all kinds in every outfit.

The Liberty Theatre at Camp Devens. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 150383ab12

Straightway the 73d set out to go the 74th one better, and in this they were most heartily supported by their commanding officer, Colonel James B. Kemper.

Colonel James B. Kemper. Forging the Sword, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1503b2274d

The regiments had considerable funds, collected for the benefit of the men when they got overseas. These had to be disposed of, for the benefit of the men, before demobilization or they were to be turned into the treasury of the United States.

So the 73d decided to spend some of their money on a "regular show." One of their chaplains happened to be a particularly accomplished man, apparently a sort of jack-of-all-trades. He was Father John F. Conoley, formerly of St. Augustine, Florida, and, before he left the service, camp chaplain at Devens. To him fell the task of writing a show for the 73d, and with a will he set himself to do it.

On January 27 and 28, 1919, " Cho Cho Sin, " a musical tale of the east, was presented by one of the finest amateur theatrical companies ever seen in Massachusetts. It was written and produced for General McCain. The men did the work.

They built their own scenery, wrote much of their own music.

Chaplain Conoley furnished the lines. Mrs. Kemper, wife of the "K. O.," assisted by Mrs. P. J. H. Farrell and Mrs. E. H. Adams, provided the costumes. The spirit of the regiment, which was to be found in every regiment of the 12th, did the rest.

The special music was composed by Sergeant George R. Tompkins, bandmaster of the 73d. The show was produced under the direction of Lieutenants Charles A. Lee and C. F. Kirschler. Sergeant "Ted" Stanley painted the scenery and the posters for the outside of the theater.

The star of the production was Private F. T. Lem. Easter, before the war a member of the Russian Ballet, and one of the most accomplished actors to be found in camp.

For two nights and one matinee the show played to packed houses. But to the officers and men in camp the opening performance was the biggest and best of all.

For just before the curtain went up that night the men of the 73d, through Chaplain Conoley, paid their own public tribute to their commanding general, who was present, as he always was, to see the efforts of his boys, and to applaud them.

Just before the lights were dimmed Chaplain Conoley appeared before the curtain. He raised his hand for silence, and then in a quiet but sincere voice told General McCain how much the men of the 12th Division thought of their chief. He voiced, also, what the men of the division had felt throughout their service, though few were able to express it in words.

Chaplain Conoley said:

Ladies and Gentlemen—It gives us great happiness to greet you—to have you as our guests this evening while we turn from the sterner duties that are incumbent upon us to frolic and play for your entertainment.

And we are, indeed, happy that you are here to help us pay tribute to one who holds our admiration, our respect, and our affectionate esteem.

And since this is his play, in that it was planned, evolved, and produced in his honor, I am sure you will all pardon me if I address myself directly to General McCain.

Sir—I trust you will accept this small effort made by the men of the 73d as a proof of the affection we all have for you. We came to this camp and into this Plymouth Division very raw material—poor soldiers.

But we all brought with us the determination to lay upon the altar of possible sacrifice that which all men hold most dear—our lives. Day after day we were trained in the ways of war under your guidance and direction; day after day we felt the small things of life fall away from us, felt the urge of that manliness and generosity that is characteristic of the trained and disciplined soldier, realized our own deficiencies, and did what I think we can truthfully call our honest best to measure up to the standard that was set for us higher up.

The result has been that every man of us is leaving the division with a bigger, broader mind and heart, motived to the bigger things of life by discipline and devotion to duty actuated by principle. The things we have learned here will influence our very thought in after days, make us better men, and give the Nation nobler, better, citizens.

Example, Sir, is the most potent factor in life—-we pattern ourselves, almost unconsciously, after those who command our respect and esteem. And your share in our life here was a powerful incentive to greater development because we knew well that nothing in the way of sacrifice or devotion to duty was asked of us that was not first done at Division Headquarters by the commanding general.

We are proud to have it said of us that we are " McCain's men of the 12th." We are sorry beyond words that we had no opportunity to express in vivid action our real devotion to your person. And, since we are so soon to be separated, we felt that we must do some little thing that would in some small way tell you of our regard. This evening's play is the result.

Sir, this is all a tribute to you! These men have worked night and day for a week—sometimes all night—in order to greet you here with this performance. When the news came of our departure, the cast of the play declared its unwillingness to leave until we should give this expression of our esteem for you.

It is the tribute of the men of the 73d to their commanding general. And so we are to take you tonight far from military terms and affairs and raise the curtain upon ancient Bagdad, while girls dance and boys sing and love and comedy and tragedy are all portrayed in brilliant costume—and it is all for you.

We thank you for your share in our lives here, for your part in the new breadth of mind and heart that has come to us all—a breadth of thought that will go, only God knows how far, to make this world a better place to live in. We have learned the real meaning of those magic words "the service"—and we leave the army not as men who turn from a stern and distasteful duty to more pleasant tasks, but as men who are better men from having lived for a time heart to heart with those exponents of service and devotion to duty who make up the armed service of these United States.

As the play proceeds and you are amused, let this thought attend you —that every word of the play, every stick of the scenery, every bit of costume, is a material proof of the affection we have for you—the commanding general of the 12th Division.

That expressed it. The spirit was there. Everybody saw it. And it was such doctrines as this that the army chaplains at Camp Devens sought to instill into the men—the strong, manly doctrines of real Americans. They all helped, every last parson. Perhaps that was one of the reasons why the chaplains of the 12th Division were so popular.

William J. Robinson, "Chapter XV: In the Grip of the 'Flu'." In Forging the Sword: The Story of Camp Devens – New England's Army Cantonment, Concord, NH: The Rumford Press, 1920, pp. 128-138.