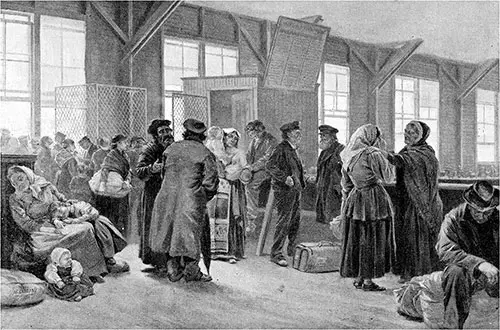

The Detained Immigrant at Ellis Island - 1893

Detained Immigrants on Ellis Island, New York Harbor. Drawn by M. Colin. Harper's Weekly, 26 August 1893. GGA Image ID # 1480e2094e

The hospitality of our land is given freely to all who deserve it, but Uncle Sam has drawn wisdom from experience, and in these latter days has come to demand at least a show of evidence that it will be rightly employed.

For the saloon passenger our doors still swing wide open. He may come and go freely, save for the inquisitive custom-house examiner and the boisterous and importunate dock cabman. But the voyager in the steerage finds his course strewn thick with obstacles.

For him the New World speedily becomes a mighty interrogation point. Failure to answer properly anyone of a score of questions, asked him perhaps half a score of times and by as many different men, failure even to allay suspicion by his manner, though his words are satisfactory, may cost him vexatious delay, or the shame and bitterness of a wrecked ambition.

His trials presumedly begin when he seeks to buy his passage ticket, for in these days the steamship companies are made responsible for the people they bring to us, and may be subjected to a fine of $20 for each unwelcome visitor, along with the necessity of taking him home again.

No sooner does the immigrant get on board ship than he is passed in procession before a physician, and if he looks ill he is put ashore. During the voyage he is put through his catechism once more.

Nineteen questions are asked him concerning his nationality, age, health, trade, resources, and prospects in the New World, and these answers must be sworn to.

Then he is drilled in the proper method of conducting himself before the examining officer in New York, and a tag is given him to be worn conspicuously upon that occasion, the purpose being to indicate clearly upon what particular sheet his answers are recorded.

Now approaches the immigrant's crucial hour. The steamer has safely passed the scrutiny of quarantine, though perhaps it had waited there with its impatient multitude from sundown until after the Health Officer's breakfast next morning.

The customs inspectors have ceased their rummaging among the baggage. The immigrants are landed at Ellis Island, and, decorated with their tags, and divided into corresponding groups, they await the summons to the inquisition-room above.

It is a strange, a stirring, and an instructive spectacle which is thus presented almost every day in the year upon the great airy second floor of the Ellis Island building.

The place is singularly suggestive of a prison in many of its aspects. Uniformed guards are everywhere—in all the passageways and at every door—to restrain the inquisitive roamer.

Here and there in the upper part of the great room are curious little iron cages, tenantless now, but later occupied by busy railroad agents and moneychangers.

On either side are other great cages one with a motley crowd of immigrants, eating, walking, sleeping, sitting listlessly with folded hands, or soothing their children's fretfulness; these are awaiting remittances or friends to take them on their journey, or else are suspects to be more closely inquired into by-and-by.

The smaller company opposite are no more miserable in appearance, though more wretched in their state. They are the rejected, to be sent home again on the next sailing of the steamer which brought them. Guards stand before their close-locked door; no one may approach them.

The lock slips back viciously to give egress to two of them closely attended. But presently the door shuts upon them again with a heavy clang as they return with great tubs of greasy, sickening stew for their companions' dinner.

Only the presence of counters here and there piled high with bread and bottles for those who care to buy, and a curious set of low iron fences forming narrow lanes lengthwise through the lower half of the room, disturb the prisonlike aspect of the place.

Presently there is a stir. A waiting figure stands before the little desk at the end of each lane, every booth is tenanted; interpreters mass themselves, and there is the distant clatter of many feet, as the immigrants crowd open-mouthed and bewildered through the further doorway.

For a moment all is confusion; the carefully ticketed groups are broken, as friends find themselves separated, or parents see their little ones stupidly assigned to another batch. At length they come down their proper lanes in single file, their queer baggage bumping against the rails and playing havoc with those in the rear.

They clearly have small notion of what is to follow. Some look frightened when halted at the desks, some angry, and some stolid, with the indifference of stupidity. Many are nervously defiant; now and again a woman's laugh sounds perilously akin to hysteria.

If their answers agree with those recorded on shipboard they are passed on. If there is any discrepancy or any dubiousness of manner, the suspect is pounced upon by waiting officials, questioned closely, and either sent upon his way, or pushed into the cage to await final investigation by the established board below.

But having passed the desks, the immigrant's worries are not over. The contract-labor inspector is there to halt such as look to him suspicious, and just now the bulk of the immigrants returned are of that class. And other agents stop and jostle them at every point to learn their destinations, and with well-meaning if irritating zeal to set them right and save them from the hovering swarm of sharpers on shore.

It is an odd spectacle, and, singularly enough, its pathos is not always to be sought in the cage of the rejected. The tear-swollen face of a young woman vainly fleeing from her shame may now and again be seen there.

But for the most part its occupants are sturdy laborers or well-dressed mechanics and their children. There is often much more that is pitiful in the shrinking shyness of maidenhood, the hopeful eagerness of young manhood, the sad-eyed melancholy of old age, or the filth and ignorance which pass beyond these desks to liberty. It is a mighty stream which courses through this narrow channel.

Fifty thousand souls walked in single file here last month. The population of a huge city, with its hopes and fears, its loves, its hates, and its sorrows, is halted here each year. The wonder is, not that misery is lighted upon, but that it is so little seen, and that the air is so far redolent of health and vitality, of youthful physical beauty and sturdy maturity, of mental alertness and of moral purpose.

"The Detained Immigrant," in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Vol. XXXVII, No. 1914, New York: Harper & Brothers, Saturday, 26 August 1893, pp. 821-822.