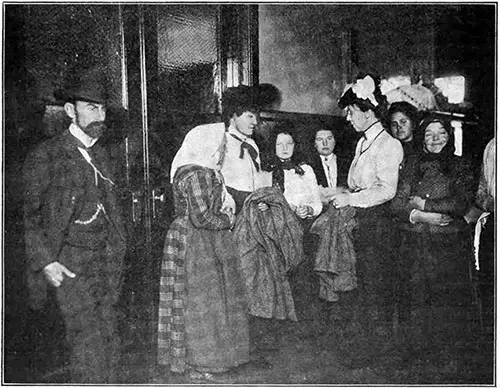

Detained Emigrants at Ellis Island - 1909

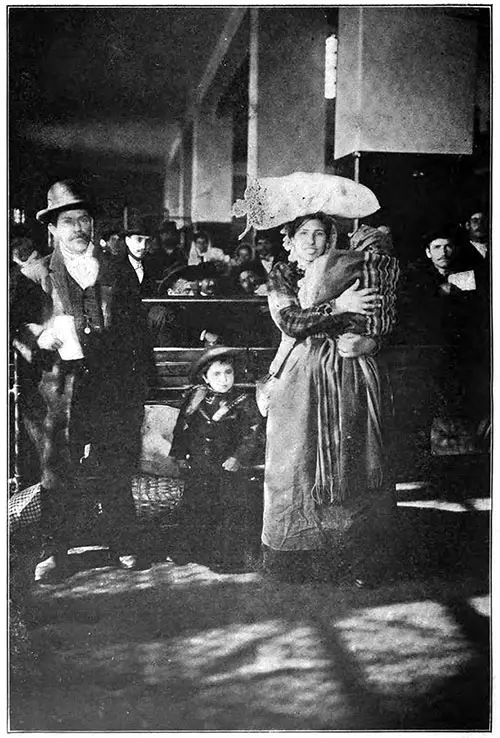

An Italian Family. The Man Tried to Pass as her Husband, but was Found to be Her Brother. The Home Missionary, March 1909. GGA Image ID # 149ade1e51

The visitors to Ellis Island on a rush day will be admitted to the gallery surrounding and above the spacious main floor over which the immigrants swarm like bees in a hive and where they can be looked down upon as they are grouped into companies of thirty each awaiting their turn to be admitted into "Americana," the land of the free!

The human line as it forms at the head of the grand stairway passes the medical examiners and then out on the main floor, where seats are provided for their comfort while waiting.

Little or nothing is known, however, of the "moral wicket" which they have pass ed on the way from the "medical" line to the group of seats where they can rest, awaiting their turn for ad mittance, and the visitors looking down are not aware of this silent feature of inspection in the system.

Those who are familiar with the routine of this great clearing house for aliens, know that this inspection goes on diligently while every ship load of immigrants is being passed in, and were it not for this phase of the work, which is carried on by the matrons and the women inspectors who go down the bay and mingle with the immigrant passengers, many undesirable individuals would pass in and add their demoralizing influence to the community.

The woman pauper, the female of questionable character, the runaway child-wife, and the unaccompanied woman may have been primed as to what to say, but their looks may belie them to their undoing.

When it is known that more than three hundred thousand women have passed this wicket in the year 1908, one can readily realize what this moral inquiry means for the country.

The moral wicket is a small gate separating an enclosure of wire from the main floor, and whithin the enclosure, there stands a small desk where the "detained" cases are registered.

Having passed the two medical inspectors, the unwary immigrant is totally ynprepared for the severest test of all, a test quite unexpected and a veritable "third degree."

The young woman suspect is for the moment held up between the two matrons, and, first learning her nationality, one or the other of the matrons asks some of these questions:

- You are alone?

- You are married?

- You are single?

- Where are your friends?

- You have children?

- Where is their father?

- Where do they live?

- You do not know?

"Just slip in here a moment." And the Scandinavian girl is ushered into the enclosure to await special inquiry, but at the hands of a woman, because if there is the least doubt of her morality, a woman or young girl is never questioned by the Board of Special Inquiry composed of men.

One of the matrons, Mrs. M. E. Stucklin, has been unusually successful during the past twenty years in detecting the little incongruities that go to make up the features of the st spect; and to the casual observer it seems almost a miracle how these guardians of the moral wicket pick out those who oftentimes confirm this suspicion and are held for deportation.

The few worls spoken in a foreign tongue, the glance at a companion, the suspicious appearance, the lifting of a corner of a shawl, or the frightened look on the face of a suspect will often lead to the detection of something that will eventually turn an immigrant back or start an investigation that will result in the uncovering of something that would otherwise pass the inspectors at the desks and permit the admittance of an undesirable or distressed case.

Aside from meeting the requirements laid down by the immigration laws and the common methods of in vestigation leading up to the acceptance of the aliens' statements, there are many side issues and little comedies, melodramas, and tragedies that are occurring continually on the stage at Ellis Island.

These little plays that are acted behind scenes (for the curtain is not raised to the curious or morbid) bring out the realities of life, its hardships and uncertainties, and nowhere in this broad land is there such a concentration of these little plays as at this "Gateway of Nations."

What leads to the begin ning of the play and who starts the music before the curtain goes up in the court room of Special Inquiry, is practically unknown—to the visitors, but it may have begun on the steamer on the way over, or when the women irspectors boarded the boat at Quarrantine, or perhaps not until the moral wicket is reached is a suggestion of trouble brought out.

Just beyond the medical line where the doctors are always on the lookout for the dreaded favus and trachoma and where the weeding-out process takes place, there is a bench or two set apart in a small wicket enclosure, and the gateway leading to it is mentally termed "moral" because of the many women suspects who pass through it.

Some pass out again and back to the shores whence they came, but, as in all cases at Ellis Island, they are always given the benefit of the doubt. It is one of the most in teresting sights in this great clearing house to watch the sifting process at the moral wicket and to get close enough to the new arrivals so that some idea can be had as to the methods of the matrons in carrying or their work.

"You see," said Mrs. Stucklin, "this part of the work would be difficult or impossible for a man to perform. There is a natural instinct born in a woman that none but she can understand, and in reading her sex there must be a sixth sense, a natural intuition, that this sort of work develops.

Some might call this sister love, but really I believe it is merely an interest in your fellow creatures. These women who pass in here are all strangers in a strange land. Perhaps few or none of them have ever seen a fine building like this, most of them are poor and unattractive.

Some of them suffer a great deal, and this naturally arouses one's sympathies and compassion— not love. It would be impossible, of course, to bestow sister love on the vast throng of women who pass this wicket in a year, but humanity and the milk of human kindness must play a great part in the work.

Some one must be responsible for the moral character of these women before they pass this house and enter a new life in a land of freedom—more freedom than they have been accustomed to, and which is sometimes prone to unfit them for better lives in congested quarters of cities or other localities to which they would naturally flock and where the moral atmosphere is not always of the best.

If this examination were not made there would be a great deal more corruption in the United States than the better half could realize; therefore someone must ascertain the moral poise of these foreign women, one of whom is capable of demoralizing a whole neighbor hood if she is so inclined."

Every woman who has a child must give satisfactory account of its father. The father must be with the family or be here to meet them, if he has sent for them, or there must be some tangible means of knowing that he is in a foreign country and that the family are here by his consent.

"See that little woman?" A matron pointed to one coming down the line with a baby in her arms and a little girl tugging at her skirts. "Well, that woman's husband is with her.

They have become separated some how, but they will get together on the floor. See how she looks back in the line of men following. She is keeping her eyes on him.

There! See, that is her husband"—pointing to a man just reaching the top step on the grand staircase. "See how he watches her anxiously It is almost impossible to mistake the father of a family, and it is quite as easy to detect when the woman is alone.

There are many cases, however, when some man has been supplied to pass the woman into the country. He plays the rôle of husband, but is invariably detected, for more than one trap is set for him.

He is either overanxious to answer questions, or he is evasive and surly; and the woman loses her nerve and breaks down or is disagreeably defiant.

Those qualities add strength to our belief that something is wrong, and on further investigation we usual ly find that a great deal is wrong." See that group—the man, woman, and two children, all Italians!

They came in on the Barbarossa yesterday, and they are going back on her when she sails next Wednesday. They would have passed in all right if the little boy had kept quiet.

The surgeon hurt his feelings when he examined his eyes, and the little fellow began to cry. "Mia da! Mia da!" Mrs. Stucklin's quick ear caught the mean ing of the baby words, and, catching up the little fellow, she tried to soothe him.

A little piece of candy from a convenient skirt pocket, where other candies reposed for other little ones too, soon brought back the smile of pleasure. Speaking in Italian, she said, "Where is your papa?" and as quickly the answer came, "Gone." Ah!

And so through the baby cry the steamer takes them home. The man was not the father, but the moth er's brother. The father had not sent for them, although he was in the West and had been there two years.

The baby in the mother's arms was his, or theirs, but what of her condition, for she would soon become a mother. It was plain to see why this man came.

There were explanations to make, questions to be asked and answered, and on telegraphic communication with the father he would have nothing to do with the woman who had trans gressed the laws of her Church; so back to Sicily they go, and her newly born baby when there would have no citizenship. Within the enclosure three attractive French girls and their escorts are awaiting further investigation.

They came over second cabin on a French liner, and the boarding offi cers as they mingled with the passen gers caught some French conversation that cast suspicion on the sextet. In stead of passing out on the pier to New York and goodness knows where, they were rounded up and sent to Ellis Island with the steerage im migrants.

They were tourists? Yes. All single? Yes. And yet they occupied three staterooms—a man and a woman in each—and the ship's papers called them "married."

The "hotel." where they were destined, a notorious house in a still more notorious neigh borhood, was evidence enough, and this gay party took the next French steamer back to the shores where liberty and license are features of their inheritance.

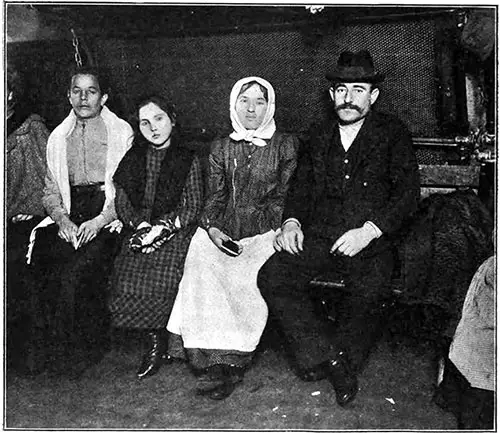

Detained Hungarian Immigrants. The GIrl Ran Away with Her Husband's Brother, Whom She Tried to Pass as Her Husband. Both are Sent Back. The Home Missionary, March 1909. GGA Image ID # 149aeb3f12

Runaway wives and husbands are as great a drug on the market as the girl who comes to be married and her lover fails to appear. Those two Hungarians sitting on the bench are very innocent appearing. They have been here a week, and will wait a few days more until the ship sails to take them home again.

The woman has run away with her husband's brother, and once in America, they are safe. But to get in—ah, that is another thing. The cableworks quicker than the steamer sails, and the consul at Budapest had the information in the hands of the immigration commissioners a day after the steamer cleared, therefore the work at this end was easy, although the names were assumed.

There are many cases of runaway women—many more than one would think. The women seem to tire of their lives of drudgery in foreign lands, and come here alone or with a child or two in the hope of bettering them selves and their children.

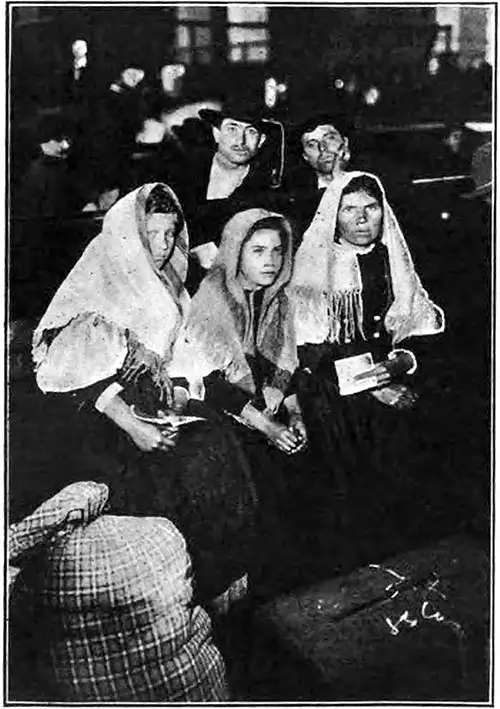

A Runaway Italian Mother and Two Girls. The Home Missionary, March 1909. GGA Image ID # 149af4321d

"We can always locate a runaway the moment she lands," said one of the matrons. "She has an air of uncertainty. She is always going to friends somewhere, but she doesn't know just where or how to get there. She has money? Yes, but not enough to support her long.

She has no trade or occupation, is of the lower class, and nothing bet ter than the sweatshop stares her in the face. It is immorality or star vation, so she is sent back."

The cunning and deceit practiced by some of these runaway women is amazing to the authorities, and hard to comprehend, for they are always sure to be found out.

The case of a runaway woman that came under supervision last fall was a revelation to the matrons, and she was set down as the record prevaricator of the year. The woman was married—she took her oath on the Bible. She had two pretty children, seven and nine years of age, and she had taught them the art of falsifying on the trip over here.

They were to be met by her father and mother, who had not seen her for twelve years and knew nothing about the children or her "marriage." Be fore the parents arrived at the Island, however, the woman and children were cross-questioned, and the answers conflicted to such an extent that they were in dividually questioned in separate rooms.

Without their mother to prompt them, the children told the truth, and when confronted with their statements she flew in such a rage that it required force to prevent her maltreating the children, who cowered and ran to others for protection.

An interesting state of affairs was developed. The woman was mistress to a gilded nobleman (?) and was going to pass these children off as his and that she was their governess bringing them to America on a visit—she to see her parents, they to see the country.

The old parents were advised of the situation before they saw her, and could not realize this until assured by the highest authorities. The poor old people were broken-hearted. They had come a long distance, they saw, and they understood.

The erring daughter confessed, she was kissed good-bye and bidden Godspeed back to the country and the people that had corrupted her; but the old people car ried home heavy hearts, and the tragedy was on this side of the ocean then.

Another similar case of an Italian mother and two daughters "detained for insufficient evidence" came up for investigation from the same shipload. This mother and daughters had studied their parts well. They had run away from Milan and the husband and father.

The family was met by the woman's old father and mother, who had been notified of their coming and came from Trenton to meet them. Before the parents arrived, however, the woman was questioned.

She said with a sad expression that her hus band and the father of the girls was dead, had been dead for three years.

The girls were questioned separately and confirmed the mother's statement, even to naming the cemetery in which the father's remains were buried and the church in which the funeral was held.

Everything appeared to be all right until the old folks arrived. They were questioned before seeing the daughter and girls, and to the utter amazement of the officials the old man exhibited a letter of recent date from the husband and father in which he said they were all living happily in Milan.

Yet in the face of this evi dence the woman stoutly maintained that the husband had died and that the date on the letter was badly writ ten and was four years old. The envelope, however, with its telltale post marks and dates, dispelled all doubt.

When confronted with the threat of arrest for perjury, the girls betrayed the mother. They were of course held for deportation, and in the days following and before the steamer sailed word came from Italy inquiring for the runaways, saying that the hus band and father was looking high and low for them.

Loud lamentations, threats, and defiance, were of no avail, and the day before they sailed away their photographs were made for record, and the savage expression on the woman's face and the frightened appearance of the girls could not have escaped the watchful eyes at the moral wicket, if all other signs had failed.

In the line from the Arabic a well dressed young lady comes with no baggage save a small grip, and no money but eighteen shillings. She has passed the medical line, but a quiet word from the matron brings a bright smile from the newcomer...Yes, she is here to be married.

"Jan" had sent for her, paid her passage, and would be here soon to meet her. One, two, three days passed, and no "Jan." Anxiety soon turned to fear, and fear to misgivings. No, she could not be admitted to go to him.

She had no friends here, and the authorities are not turning good-looking, well-dress ed young women loose in this country to fall prey to the unmitigated scamp who is ever on the lookout for the un wary.

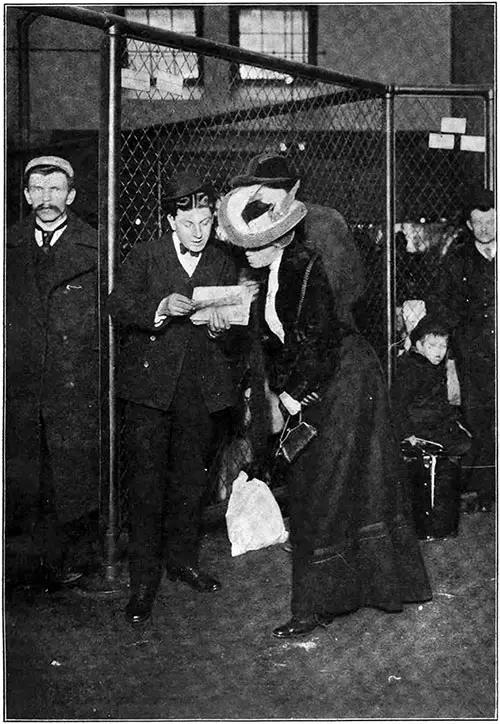

A Young Immigrant Woman Receives Bad News About Her Husband to Be: Telegram from the West, "He is Dead." She Must Go Back. The Home Missionary, March 1909. GGA Image ID # 149b3c2442

She has telegraphed, but no reply comes. Among the list of dead in a north western accident appears the name of one "Jan Sorenson," who has tickets through to New York in his pockets.

An inspector reads of the disaster two days before the girl arrived, and by the merest chance remembered it and connected the names. And then the telegraph works again.

Then sorrow is the portion dealt to this girl, for the answer comes, "He is dead." She must go back. The matrons and missionaries cannot comfort her. The joyful trip over is a funeral march back, and she can never see the face of her lover and husband to be.

Every shipload brings its portion of sorrow and suffering, and gayety is almost out of the question at Ellis Is land among the class, that struggle, and these are in the large majority.

Here you see more misery than can be imagined, misery born of perpetual hardships, and it is in quest of better times and an easier life that the hun dieds of thousands knock at our doors annually for admittance.

Death in the steerage casts gloom over a ship load of immigrants, and they do not recover from the effects of it until long after they have passed out from the gateway.

The other day a woman just landed and detained on account of the illness of her child, had lost her baby at sea. Her agony and grief were pitiable, and on the third day after arriving here the other child passed away, after heroic efforts on the part of the hospital physicians to save it.

Nothing could be done to check her grief, and it seemed as if she would mourn herself to death. Her husband came for her the fourth day, and hardly knew her, she had changed so in her week of tribulation.

It is for these poor women our heart strings are wrung, and, as Mrs. Stucklin says, no one can comfort them or give advice better than the matrons, who seem to be able to cope with every situation, though many of them are most trying.

Of the many sides to the "moral" question. that come under the watch ful eyes of the authorities, none per haps are so puzzling as the complex ones such as the laws of foreign countries permit.

"That stolid-looking mother and four children must go back to Russia," said a matron. "The question is too complex to be handled here. The father of the two boys came here some years ago to make a home. Two years after his departure word reached the mother that he had died.

She married another man, the father of the girls, and before, the second was born he ran away to America. The woman had moved from her first abode and a letter from her first husband never reached her.

An Immigrant Family Comes to America to Find Father. The father ran away to America and married another woman, and a former husband turns up unexpectedly. The family must go back, and the difficulty cleared in the home country. The Home Missionary, March 1909. GGA Image ID # 149b4d9f1f

The parents furnished money for her to go to America to find husband number two. and when she arrived, merely by accident she met husband number one, who had come to meet his brother arriving from Russia.

The woman, then with two living husbands and two sets of children, could not go to her first husband as he would not accept or care for the children by husband number two, and as number two could not be found, the woman and her children went back where they authorities in her home village can have the pleasure of unraveling the tangle.

Every woman who is about to become a mother is stopped. If she can communicate with her husband and give evidence that she has been legally married and has money enough to support her or friends to care for her, she is passed in.

If, however, a woman who is not legally married should enter the United States and a child be born, there would be more harm done to the woman and child than one unaccus tomed to this sort of business is aware of. The child would not be recog nized here, the woman would be scorned, and we should be severely censured for admitting such cases.

This is the greatest and hardest part of the work we have to do, and to de tect these cases is the most difficult and trying on our sympathies. A case of this kind is always detained until the person responsible for the wrong is discovered or until the wom an confesses that she is not married.

Then she is returned." The immediate work for the day was over, and one of the missionaries led the way to the "women detained" rooms, where a sorrowful young girl hardly more than sixteen was reclin ing on a bench crying.

"This," said Miss Matthews, one of the angels of comfort to the really needy, "is the most pitiful case we have had in a long time. This poor girl comes with practically nothing but her sorrow. We have given her clothing and tried to comfort her.

The Betrayed Polish Girl Who Came to Find Her Lover, Is Detained at Ellis Island Pending the Outcome of the Inquiry. The Home Missionary, March 1909. GGA Image ID # 149b8cc9db

She comes from Poland, an outcast from her parents' home. They have sent her over here in quest of her lover and betrayer. He is a friend of her brother, and if we can find him perhaps the powers will be kind."

The machinery that was set in motion at Ellis Island resulted in the inspectors locating the brother, rounding up the young man responsible for the girl's condition, and while they had to go to Hartford to get him, he was brought to Ellis Island, at the eleventh hour, just on the eve of her deportation.

He married her and promised to look out and care for the young child wife. He has kept his word, for he is under Government inspection for three years. But Some cases of this kind are not so easily disposed of, and the last scene of the tragedy is played before a foreign audience out across the sea and far from the land of promise.

Those who give the matrons the greatest trouble and are hardest to manage, they say, are the deceitful, willful, and secretive girls. There is a kind of savagery about their natures that is difficult to subdue in order to elicit from them the information necessary for our satisfaction.

This unconquerable element is a menace to the population of the tenement quarters and the farming districts in to which they go, and if proof against them cannot be had, they are admitted.

The woman who is found to be abso lutely malicious and really criminal in her ideas and thought is speedily de ported, and among the undesirable class we are always on the lookout for the professionally immoral girls that come here from Paris, Brussels, Ham burg, and other cities in Europe, to gain admittance into the notorious sections of our large cities.

There are many women who are so sly and so successful in covering their real natures that they pass, for our in spection is naturally limited to a short time only.

These are of the class that fill our jails and which if caught within the three-year limit are deported. After this brief recital, do you wonder that there is a moral wicket placed at the gateway, and do you not think there is a necessity for it?

Joseph H. Adams, "The Moral Wicket at the Gateway of Nations," in The Home Missionary, New York: Congregational Home Missionary Society, Vol. LXXXII, No. 10, March 1909 pp. 684-694