The Immigration Question – 1888

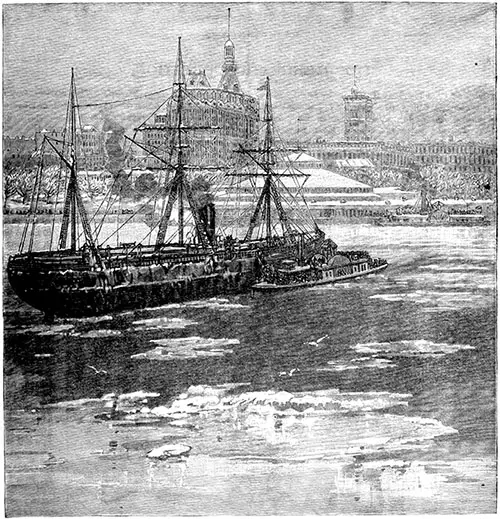

View of the Battery and Castle Garden -- The Haven of Incoming Millions. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, March 1888. GGA Image ID # 14bd4c4de7

Richly Illustrated article from 1888 described the vast immigration and alarms set off in two different degrees. It threw an enormous quantity of skilled and unskilled labor on the market, and native-born mechanics especially began to feel the effect of the competition.

This land of ours has been built up by immigration, and this system of filling up a country began ages ago. In this ancient continent, older by far in its present state than Europe, there must have been, from time immemorial, emigrations of vast hordes and nations, so that successively each desirable bit of country was held by a different set of inhabitants.

Tribes which were rising in the scale of civilization, acquiring arts, and showing progress in manufacture, in agriculture and in government, were swept aside by ruler und more warlike tribes, which, dislodged from their homes, swept down on the more peaceful and civilized, and therefore less warlike, races.

Every Indian tribe in our land, when the white settlers first came, had a tale to tell of how its ancestors came to the part of the country where they wore found. They were but the descendants of emigrants from other parts. Then came the immigration from Europe.

The earliest may have antedated history, when convulsions that did not affect America altered the western shores of Europe and submerged the islands and. lands over which the Atlantic now rolls —lands that, in earlier days, gave a pathway for hordes to pass to our continent.

We all in this land now, except the red men, are emigrants from Europe or descendants of those who landed here after the middle of the sixteenth century.

The first emigrants were hardy, daring men, to seek to make homes in a new and untried world, where all but earth, air and water was new and strange; where none of the animal and vegetable food supplies to which men were accustomed, could be found; where no cattle and sheep grazed in the meadows; where no fields of wheat or rye or barley nodded with the wind: where no orchards stood from year to rear with ripening fruit Many of the first bodies of settlers, like the Spaniards in Virginia, or the English in Roanoke, or the French in Carolina, failed utterly and perished, except the few who escaped from a land that seemed accursed of God.

But stouter and more enduring men undertook the task, and European emigration obtained a hold on the Atlantic coast that has never been lost.

The moment permanent settlements were made, immigration began. The forests were to be cleared, the land broken up and cultivated. There was daily need of men to ply the mechanical arts, to ran the smithy and the carpenter shop, to build the boats on which most of the early communication was carried on between the waterside settlements.

Voluntary emigration furnished a steady increase; but England soon began to send over men and women from the multitudes that crowded her jails, and after a civil war, such as that of the Puritans against the Monarchy, prisoners taken in the field or inhabitants of whole districts were shipped to this country, to be sold as indentured servants for a term of years.

The former was, of course, a sorry set, from whom little could be expected—idle, vicious and without any energy to begin a better life. The political prisoners were a better stock for a new country.

The 50,000 healthy, industrious Irish women sent over by Cromwell, and the Scotch Highlanders who met the English regulars at Preston Pans and Culloden, though they failed to win the day, were good stock to form after generations of stalwart patriotic citizens in this country.

A third class of emigrants were those who, in the last century, came over as what were called Redemptioners.

As the sale of indentured servants had become common, this new system, based on it, arose. Vessels destined to obtain cargoes from America offered to take over those who wished to reach our shores, but lacked means to pay their passage money, under certain conditions.

The ship gave them a passage and food during the voyage. For the amount thus due, each passenger had to redeem himself on arrival. If he had a friend, countryman or relative to pay the debt against him, he stepped forth on the land of his adoption a free man.

If not, he was sold for the lowest term of years at which any one at the auction would agree to take him. The good mechanic, or man who showed that he could readily make himself useful, was of course sold for a short term, while the unfortunate, out of whom a farmer thought that he could not easily obtain enough labor to repay his outlay, was knocked down for a long term.

This class of immigrants did not seem a very promising one. Yet all were not the shiftless set we would be apt to suppose them. Several of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were men who came over as Redemptioners, landing here without a penny, but they were men of some education, of great energy and perseverance, who soon rose to be leaders among their follow-men.

Naturally those sold as Redemptioners or indentured servants endeavored to escape from their condition of servitude, and the early newspapers of our country abound in advertisements for such fugitives, who sometimes, perhaps, could justify their action by the harsh and cruel treatment to which they had been persistently subjected.

We find an indication of the grade of some Redemptioners in the fact that many became schoolmasters in different parts of the country, and occasionally a delivery into the newspapers of the last century will light on an advertisement for a runaway schoolmaster, who had not fully served out his time as a Redemptioner.

The immigration to this country in the last century was large and widely distributed. There were no great ports at which all the commerce centered, and many towns, from Salem to Savannah, did a large foreign trade then compared to what they do now.

The extent of the immigration in the last century may be judged from a few entries in the papers of the day.

August 13th, 1735, a vessel at Portsmouth, N. H., with 120 Irish passengers; July, a vessel at Charleston, S. C, with 250 Swiss. At Philadelphia a single paper, in August 1736, notes the arrival of two vessels with 425 passengers.

The New York Gazette, 13th-20th September 1736, notes the arrival of one ship with 345 passengers from Ireland, and exclaims, "One thousand souls in twenty-four hours!"

The Snow Catharine, from Workington, Ireland, was wrecked on Cape Sable, and nearly one-half of her 202 passengers were lost.

Great as this immigration was compared to the actual population of the colonies at that time, there seems to have been no general system of legislation adopted to provide for making the immigrants useful to the little community.

They seem to have been absorbed quickly and readily, and seldom to have become a burden. Maryland, at that time fearful of any increase of its Catholic population, passed several Acts, imposing heavy and heavier fines on every Irish Papist imported into the province of the Baltimore; but such checks on immigration were rare and unusual.

The number of very wealthy immigrants in early times was very small, and of those who came over with means, intending to create great estates or build up great mining or manufacturing interests, to continue in their families from generation to generation, scarcely enough succeeded to be at all remembered in our day.

The Van Rensselaer family, in New York, is one of the few exceptions; while most, like Peteri Hasenclever, expended thousands in opening mines and works by which others ultimately profited.

The immigrants were thus in the main equal, comparatively, in means, and all except the Germans who settled in Pennsylvania and the Upper Hudson and Mohawk, soon lost their own language, and after one or two generations their descendants could not be distinguished from those of English origin.

The immigrants were thus readily absorbed in the general community, and no complaints seem to have been made in regard to them. Nothing in the newspapers or occasional writings of the colonial period shows any jealousy of the incoming immigration, or fear that the newcomers would fail to render themselves useful accessions, or prove unfit to be absorbed into the body politic.

When the Revolutionary War raised the colonies to the rank of a recognized nation under a republican government, everything about it appealed to the people of the Old World.

Europe, crushed with debts, with new wars that rapidly came on, increasing the difficulties of prospering, or even eking out an existence, made emigration the only hope for thousands.

A new country, where land was cheap beyond the dreams of men, where grinding landlords, oppressive taxation, standing armies, and privileged closes were unknown, where every man could acquire wealth and position by industry and ability, was, in the eyes of the downtrodden, a new paradise.

Beginning under the old Redemption system immigration to this country rapidly developed and was fostered by our Government. It soon outgrows the old system, however, and vessels competed for the transportation of those who wished to come to America.

Those who settled here saved up their earnings to send out for other members of the family; and as the population on the coast began to send out detachments to occupy and improve the lands in the interior, emigration furnished numbers to join in each new settlement.

The comfort of the passengers was little regarded by the owners or captains of ships, and their accommodations were often little better than those of a slave in the vessels that bore the unhappy Africans on their involuntary emigration to the shores of America.

Some of the earliest Acts of Congress in relation to immigrants were intended to check the inhumanity of this system. A law passed in March 1819, limited the number of passengers that a vessel could carry to two passengers to every five tons of its bulk as ascertained by custom-house measure.

But in those days of sailing vessels, when voyages were of uncertain length, the sufferings on these ships were very great under the best circumstances.

The rate of emigration increased after the second war with Great Britain, yet in 1820 the number was only about 8,000; but' in 1828 no fewer than 27,382 arrived here. After 1831 the number made a sudden advance from 22,000 to 60,000 in the famous cholera year.

Ten years later, 104,565 arrived; in 1847, 234 968; in 1850 more than 300,000 came to swell our population, and in 1854 the immigrants numbered more than 400,000; but then came a falling off, and, in 1861, when our Civil War began, the statistics show less than 100,000. Then the figure rose again, and in 1872 was more than 437,000.

When steamships became numerous, they began to take large numbers of emigrants as steerage passengers, and their superior accommodations and quick passages soon secured almost the whole of the business, to the great advantage of humanity; for though laws had been passed to secure the comfort of this class of passengers, the sailing vessels showed a terrible record of mortality, the deaths being fifteen in every thousand they carried, while the steamers lost only about one in a thousand.

The vast immigration in time excited alarm in two different degrees. It threw a vast quantity of skilled and unskilled labor on the market, and native-born mechanics especially began to feel the effect of the competition.

This led to associations to endeavor to remedy the matter. As many of the immigrants were Roman Catholics, the increase of that religious body alarmed some of other denominations, and as many immigrants, especially Irish, availed themselves of existing laws to become citizens after the term of five years, their activity in politics gave additional umbrage.

These grounds were the motive which led to the organization of the Native American party, subsequently called, popularly, the "Know Nothing party." Its main object was the extension of the term for naturalization to twenty-one years and the exclusion of Catholics from office.

Yet though this party at times obtained local success, and more than once put forward a candidate for the Presidency, and led to alarming and destructive riots, this organized hostility did not at all affect the increase of immigration.

The hostility was, in fact, confined mainly to the Eastern States, while the West, which needed men to develop its resources, gladly welcomed the newcomers, and Germans especially pushed in that direction.

Their numbers, at first small, became in time about half that from the British Isles, but in 1854 there were 215,000 from Germany to 160,253 from the British Isles.

In view of the great influx of Swedes from Northern Europe and Italians from the South, at the present time it is curious to find that in 1823 only one Swede arrived, and in 1832 only two Italians, while in 1882, 27,484 natives of Italy and 57,664 of Norway and Sweden entered the gates of Castle Garden.

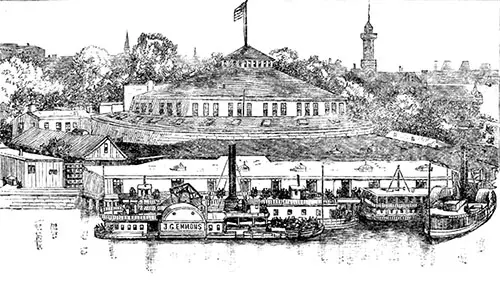

View of Castle Garden -- Several Barges Bringing More Immigrants Docked in Front. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, March 1888. GGA Image ID # 14bd9e5f28

At the present time Germany sends the largest number, England stands next, while Ireland occupies the third place in the list, though sometimes it takes the second. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, Norway and Sweden, Italy, Russia, Scotland and Denmark, represent the other great sources of new population.

Of 321,814 who arrived in 1886, about ninety-six thousand were from the British Isles, while more than twice that number were sent by Continental Europe.

But Europe alone does not furnish all our immigrants. Asia, too, has begun to contribute largely to our population, raising new questions, and calling for special legislative consideration and enactment.

The development of California and the demand for labor there attracted the Chinese, and their numbers increased with great rapidity, so that, by 1874, 144,328 had arrived.

A bad feature of this class was that they were really serfs, imported by large trading companies and controlled by them. Very few Chinese women came, and those who did were used for the worst purposes.

Living apart, ignorant of our civilized social rules, or indifferent to them, these Chinese wore, in a manner, not amenable to our laws. It was extremely difficult to trace or punish crime among them.

There was soon a movement against, the further introduction of this undesirable class. Then came a protest against cheap labor among the working class, and a protest against the heathen vices implanted on our land was made by many religious and moral citizens.

Local violence followed, and Congress was called upon to regulate the system of importing Chinese. A law passed in 1885 expressly prohibited the importation of aliens for labor or service in this country, by contract or agreement, express or implied, parol or special.

This was intended to apply to the Chinese immigration, but a church is at present arraigned under this law for making a contract with a clergyman in Europe to come over and help save their souls!

The Mormon progress in Utah, with its shameless revival of polygamy, has been mainly built up by immigration, planned, concerted and fed by Mormon agents in Europe, and, to a great extent, in Scandinavia.

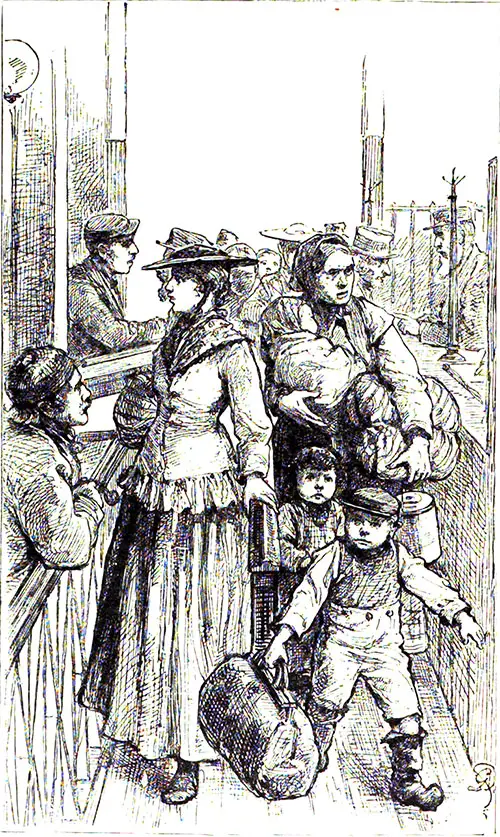

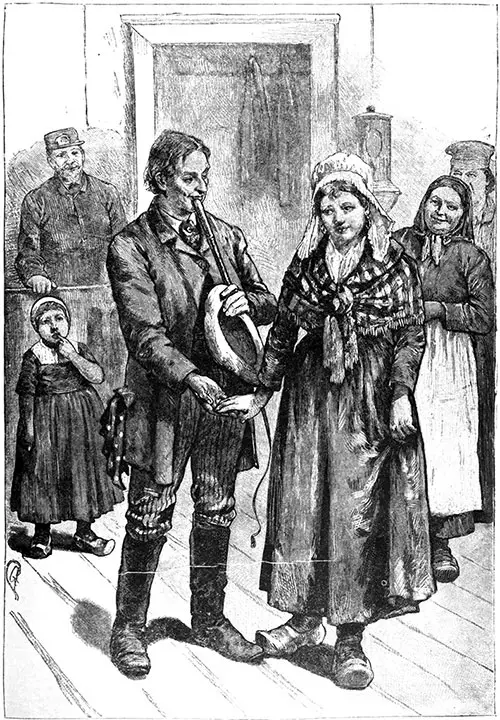

Scandinavian Immigrants at Castle Garden -- Their Destination -- Utah. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, March 1888. GGA Image ID # 14becd5adc

The Mormon system grew by the neglect of Congress to check it, till it had acquired a strength making its suppression difficult. Recent laws have aimed to suppress polygamy, but as long as unfortunate women are openly introduced into the country, under sanction of Government, to be forwarded to Utah, the evil must increase.

To check their entrance into the country seems to many the only effectual means of checking the further increase of polygamy.

The system of government in Russia and some other European countries has created a vast network of secret revolutionary societies, in which the principles adopted and propagated at last reached the point of aiming at the abolition of all rights in personal or real property, and of all government.

Many of these Communists, Nihilists and Anarchists have sought refuge in the United States, and, as has been shown at Chicago, disseminate their ideas and extend their organization mainly among the Continental element here.

They show as great a hostility to the existing social and political life of this country as they do to the most arbitrary and tyrannical monarchical institutions in Europe. To meet this new difficulty means are yet to be devised.

As New York became the great port where the immigration from Europe centered, the State, in 1847, created a Board of Commissioners of Emigration, and required every ship bringing immigrants to pay a certain sum per head for each.

This money was used by the Commissioners of Emigration to protect alien passengers from fraud and imposition, to advise them how to reach their destination, and, as far as passible, see to their welfare.

All alien passengers for whom the rate was paid were, in case of sickness or want occurring within five years after their arrival, to be supported or relieved by the Commissioners of Emigration out of the funds in their hands.

The building at the Battery known as Castle Garden, became the receiving place for all immigrants, and continues so to this day.

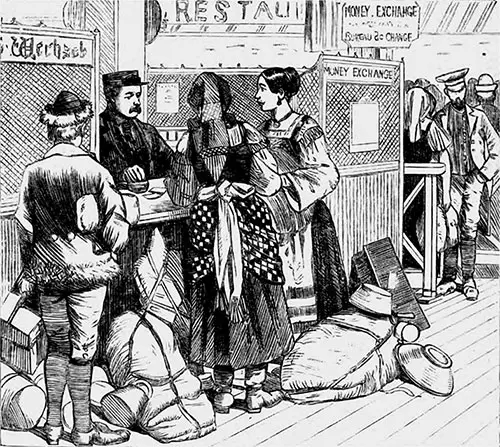

The Money Exchange at Castle Garden. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, March 1888. GGA Image ID # 14bda6e48c

For the sick and helpless large and well-fitted buildings were erected on Ward's Island. Under the management of this Board great good was done; the poorhouses of the country were relieved of recently arrived immigrants, and these newcomers generally protected from fraud, and enabled to reach the homes they had selected, in most cases, soon became thriving and prosperous, according to their capacity.

Castle Garden, the great center of the immigration into this country, presents a strange and picturesque scene worthy of study. Under the system built up by years of experience, these thousands of men, women, and children, arriving generally ignorant of the language and ways of the country, are rapidly parceled out, some conducted to the steamboat or railroad lines, others sent to Ward's Island; others kept till friends arrive, or applications for various kinds of labor take them from the employment bureau.

Licensed boardinghouses receive those who have to wait here, and at every step there are agencies to prevent fraud and imposition.

When the immigrants reach Castle Garden, they pass in single file into the rotunda, and the police officer passes them toward the registering-clerk. Here each one is asked his or her name, place of birth and destination, the replies being entered in an enormous ledger.

Then comes the question of departure—trains, boats, etc. — and the queries, uttered in French, Italian, Irish, Danish, Finnish, Russian, and fifty different dialects, are briefly but courteously responded to.

Those who propose remaining in New York emerge into the Battery Park and are cared for by the agents of the Inman Line, who see them safely housed in respectable boardinghouses.

Those who are compelled to wait for the evening trains for the West and South encamp in the rotunda, gypsy fashion, and sit, sprawl, crouch and lie in every attitude of indolent nonchalance.

Home of these groups are intensely picturesque. The quaint costumes of Danish and German villages, the rich colors of Connemara cloaks, and the thousand and one hues of the beribboned lassies of many climes, blend in glowing contrasts.

Meals are partaken of; the "tay" is wet and the lager is foamed; children romp and play; the old people doze, and the younger take up the thread of the f1irtations commenced on the bounding billows, and resolve to make the most of their time ere the bitter word of parting.

A Farmer from the Interior Seeking a Wife at Castle Garden. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, March 1888. GGA Image ID # 14beab1e6d

The hour at length arrives when it becomes necessary to move toward the train, and then there is a mighty upheaval of human forms and human impedimenta.

The shipping interests struggled earnestly against the laws of New York, and ultimately obtained a decision of the United States Supreme Court, on the 21st of March, 1876, declaring the whole system of New York to be a violation of the Constitution of the United States, as interfering with the exclusive right of Congress to regulate foreign commerce.

The case had been elaborately argued and was long under consideration by the Justices. Miller, Justice, delivering the opinion of the Court, said in regard to the Legislature of New York:

"We are or opinion that this whole subject has been confided to Congress by the Constitution; that Congress can more appropriately, and with morn acceptance, exercise it than any other body known to our law, State or National; that by providing a system of laws in these matters, applicable to all ports, and to all vessels, a serious question, which has long been matter of contest and complaint, may be effectually and satisfactorily settled."

But in the court of common sense it would seem sound reasoning to hold that a power so indefinite that Congress had for eighty-nine years neglected to exercise it, although the cries of suffering humanity and the welfare of the whole country demanded action, ought to be considered as abdicated and waived.

This decision, given in hesitating tones, affected not only the State of New York, but all other States on the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Pacific; threw their ports open, and left them unprotected against the introduction of paupers and criminals, while it deprived the immigrant of every shield against fraud and oppression.

But Congress, which had for eighty-nine years been indifferent to the suffering and the welfare of the millions who poured into this country, which had shown its disregard whether these newcomers were to be made into good and valuable citizens or allowed to add new impetus to the increase of the pauper and criminal classes, was not to be roused to action by any decision of the Supreme Court.

The subject afforded no opportunity for the creation of lucrative offices; it merely concerned the public welfare; a topic well adopted for rhetorical treatment, but not of a character to influence public business.

The result of the decision on the Commissioners of Emigration was disastrous. Their means of doing good were at once cut off, and not only that—they were at once sued by the great shipping companies for the money which they had received and expended for the benefit of the immigrants.

As the shipping companies always included the tax in the passage money, decisions in their favor would have put into the coffers of the steamship lines money which came really from the immigrants, but which would never be refunded to them.

The Commissioners of Emigration at once applied to Congress to pass a law similar in effect to that which the experience of years had placed on the statute-book of New York, and applied also for a law to relieve them from inequitable suits against them in name, but really against the State of New York, whose agents they were.

On the 19th of June, 1878, Congress did indeed pass an Act preventing any such actions, but it was not till July 22nd, 1882, that Congress passed an Act regulating the great matter of immigration.

Meanwhile the State of New York, with greater humanity and a higher sense of the national good, maintained the Commissioners of Emigration and enabled them to continue in some degree the beneficent work which had for years done honor to the high-minded and unblemished men who directed it. From 1876 to 1880 the General Government, or un-government, did nothing to relieve New York of this burden so generously assumed, and not till the State had expended more than six hundred thousand dollars did the United States establish an "Immigrant Fund," arising from a tax of fifty cents per head levied under an Act of August 3d, 1882.

The Acts of Congress were scarcely dry when suits were begun to declare them unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court was asked to stultify itself by declaring Acts unconstitutional which it had declared it the power and duty of Congress to pass.

The Court again, by the same Justice Miller as its mouthpiece, on the 8th of December 1884, gave its decision that the Acts of 1882 were constitutional. But the funds provided by the Acts of Congress are totally inadequate to the wants of the Commission, and much of the good it formerly accomplished it is now unable to affect.

There are thus various questions coming up before the people in regard to future immigration—whether further immigration is to be encouraged ; or whether checks are to be placed upon it, further than those which already prevent the landing of those who, by reason of their condition as convicts, paupers, or persons unable to acquire a living, are almost certain to become a public burden; whether the Chinese and Mormon questions can be further solved by additional legislation; and whether Anarchism can be checked by excluding the propagators of its doctrines.

The question, also, arises whether a revision of the naturalization laws is required to prevent Mormon and Anarchist leaders from employing their dupes, still ignorant of the real spirit and tendency of our liberal governments, to control elections, defeat needed legislation, and promote, as far as in them lies, a return to chaos, by dissolving all the bonds that blend men together in Christian society.

Naturalization is sure to come up. A general law of Congress will affect comparatively little, as even for national offices the qualifications of electors are in many cases those necessary to vote for the most popular branch of the State Legislature.

And as the Western States confer this right on actual settlers, irrespective of United States naturalization, Congressional laws will not materially affect them unless the Constitution of the United States is amended.

There are, thus, a number of questions regarding immigration which call loudly for a general systematic and philosophical treatment of the whole subject, after full discussion, by the ablest of our statesmen.

If the topic is consigned to neglect, as it has been too frequently by Congress, evils of no little magnitude may suddenly come upon us to add weight to the growing sentiment that the General Government, as at present organized, is a detriment, not an aid, to the general progress of the country.

There will, of course, be a wide range for opinion from those who hold all check on immigration unwise and impolitic; maintaining that it is impossible to decide whether the man who comes penniless, with a strong will and determination to succeed, or the man who comes in the cabin with abundant means, is likely to be a public charge or a general benefit to the country.

If men sold on the docks as Redemptioners, in the old time, rose to be members of the body which shaped the destinies of America, held the spontaneous allegiance of the people and maintained a seven years' war against the greatest power in Europe, why cannot the man who, today, steps penniless on the dock achieve as much?

They point to the many who come with means, but who are paupers in a few years from want of thrift and judgment, injudicious investments, rash speculation, over-confidence in others.

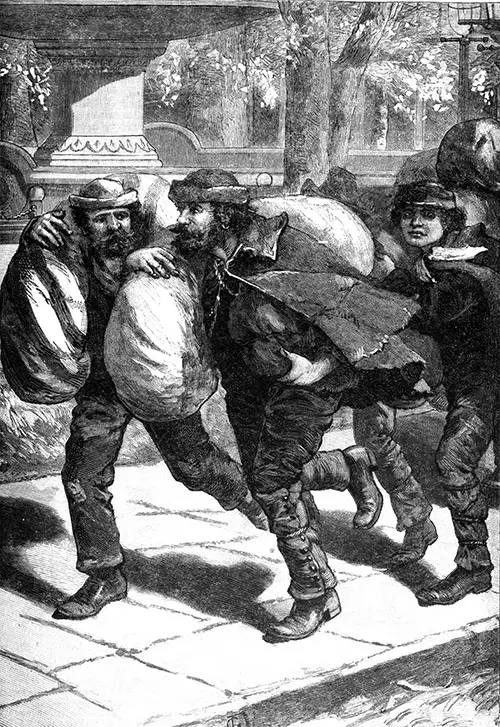

Italian Immigrants Sprinting Towards the Railway Depot from Castle Garden. Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, March 1888. GGA Image ID # 14bedbb176

In the brain of a cripple may be inventions to surpass those of Edison. As no one can read the future, or tell what the innate capacities may develop into under our system, why refuse any man an opportunity?

Others, at the other extreme, would require from every emigrant a police certificate from Lis last residence, countersigned by the American Consul, that the bearer has never been a convict, or pauper, or placed under police supervision as a dangerous character.

In 1798, during the Administration of John Adams, Congress passed the famous Alien Act, by which the President was authorized to expel any alien plotting against the peace.

This Act drew great obloquy on the Federal party, and the popular mind has been strongly opposed to entrusting any such powers to the General Government; but early in the present session of Congress, Mr. Adams, of Chicago, introduced a Bill giving the President power to banish revolutionary aliens plotting against the peace and safety of the state.

The more favorable plan would be to invest the Courts with power to act summarily in such cases, and there is a growing conviction that the Government should provide some means by which it may protect itself from aliens who are professed revolutionists, and whose only occupation is to undermine the Government.

Others would wish some steps taken to disabuse the ignorant women brought over by the Mormon agents to swell the number of polygamous wives in Utah, and show the poor creatures that they are going to do what the laws of the country forbid, and what must ultimately entail misery on them, and cover themselves and their children with disgrace and shame.

Others would counsel the passage of an Act applicable to all Territories, under which any woman, not the sole legal wife of a husband, who bears a child, may be arrested and sent out of the Territory to her native place, here or abroad, the cost of transportation to be levied on the putative father of the child ; and requiring copies of such statute, in their own language, to be distributed to all women landing here, that they may not claim to have acted in ignorance of the law.

The Chinese question is yet in a crude state on the statute-books, and many improvements will be suggested.

From all sides, therefore, comes a call for a statesman like treatment of immigration, and the host of questions that have already arisen or may soon arise in regard to it.

The prospect, sooner or later, of a great war in Europe, that will swell the influx of newcomers, makes it imperative to prepare in advance, and not patch up matters by ill-advised and hasty legislation.

"The Immigration Question," in Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, New York: Frank Leslie's Publishing House, Vol. XXV, No. 3, March 1888, pp. 259-267.