Malt Whisky and “Silent Spirit” - 1900

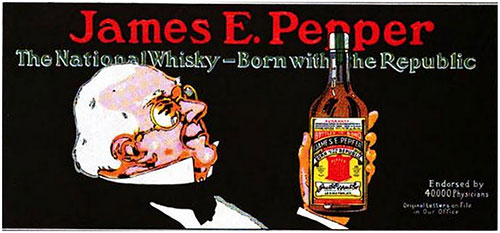

James E. Pepper: The National Whisky © 1913

0N the subject of blending whiskies much might be written. Recourse to the practice of blending proved that by a mixture of several brands of pure whisky the too pronounced characteristics of each were toned down and blended into a harmonious whole. Patent still spirit here found its sphere of utility.

Being itself practically tasteless, it was recognized as a valuable aid in toning down flavor, and in this respect its use fulness, when it is employed scientifically and with integrity, is apparent.

The blending of whiskies, as the blending of wines, is a scientific operation, which it is hardly necessary to point out is achieved with conspicuous success in the case of several well-known blends, than which no better can be bought for money.

At the same time the practice of blending is the opportunity of the unscrupulous manufacturer of cheap and semi-poisonous rubbish. The grain spirit is so much less costly than the malt that the temptation to raise it to a chief position in the blend, instead of making it a mere qualifying agent, is in some cases irresistible.

Hence the crowd of cheap and unwholesome whiskies, made for the most part of patent still spirit, with a mere qualification of malt, which find their ready sale in cheap neighborhoods through the lower-class wine and spirit merchants and ochers.

It is after all a matter that rests with the public, and if people will be credulous enough to believe that whisky worthy of the name can be produced for sale retail at 15. 9d. or as a bottle they must take the consequences of their excess of faith.

To state the case clearly from the health point of view, the distinguishing property of malted grain is the amount of volatile ethers contained in the spirit produced from it. These ethers are similar to the volatile matter in wine.

They improve and develop with age, possess a bouquet and aroma of their own, and produce a peculiar and agreeable dryness on the palate. In well-matured pure old malt whisky the alcohol is greatly reduced while the ethers are developed from it.

They act directly upon the heart, accelerating its action and producing a warmth and exhilaration of spirits which pass off, leaving no ill after-effects.

New raw grain spirit is on the other hand, highly alcoholic and deficient in the

power of producing ethers. It is made from raw or unmalted grain—barley, on

account of its price, being less used than Indian corn. The “patent” stills in

which it is made are so searching in their action that they will extract spirit from even damaged grain, no small proportion of which forms the basis of a great deal of the inferior whisky which is sold.

Amylic alcoholic or fusel oil, which is the highly intoxicating element in new whiskies is predominant in spirit of this class. Its evaporating point being lower than that of ethylic alcohol, it ultimately disappears as the spirit matures. Hence the improvement of whiskies with age.

The amount of fusel oil in well-matured whisky is so trifling that its extraction would, so chemists opine, be physiologically a matter of indifference. Dr. Thudichum states the case against the product of the patent still as follows:—“

It derives its name from the fact that it is mere alcohol and water, having no distinctive qualities, telling no tales to nose or palate of the source from which it was obtained, and hence,

in the almost poetic language of the trade, it is commonly called “silent spirit.” The owner of a patent still, instead of being confined, like a whisky distiller, to the use of the best materials, is able to make his spirit from any, even spoiled and waste materials, and with little reference to any other quality than cheapness.

The worst of the spirit thus produced is fit only for methylation, preparatory to being used for trade purposes, exclusive of consumption as a beverage. When intended for a beverage, it must be rectified and flavored.

It thus serves as a basis for the implanting of artificial flavors, which may be those of sham whisky, sham brandy, or sham rum. The presence of grain ethers is the condition of the genuineness of whisky.

Silent spirit undergoes no change by keeping, and must be flavored to become drinkable. For that purpose it is either made smoky to become like Scotch, or it is mixed with Irish pot whisky, to become like Irish whisky."

“Cellar Notes: Malt Whisky and Silent Spirit,” The Epicure: A Journal of Taste, Vol. VII, No. 74, January 1900, p. 153-154