Frying - Vintage Cooking Process

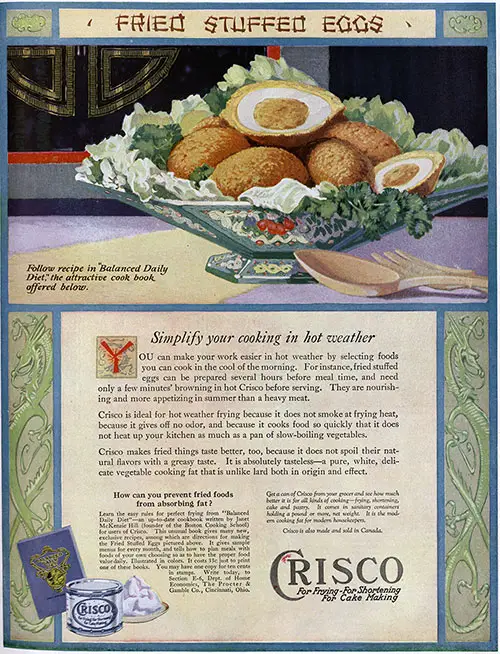

Fried Food Healthful as Well as Delicious - Crisco Vintage Ad © 1920

Frying is cooking in very hot fat, and the secret of success is to have the fat hot enough to harden the outer surface of the meat immediately and deep enough to cover the meat. As the fat can be saved and used many times, the use of alarge quantity is not extravagant.

In frying properly, the food is immersed in a bath of fat, the temperature varying with the material to be cooked. For croquettes and like cooked foods a small bit of bread must brown in forty counts, while for fritters, doughnuts and all uncooked foods, sixty counts is preferable.

Overview of the Process

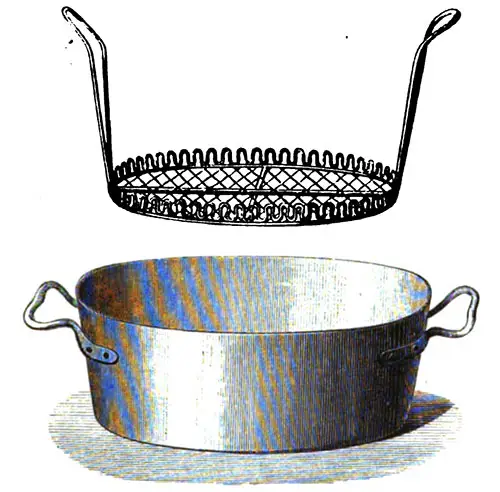

Frying Kettle with Basket Drainer © 1869 The Royal Cookery Book

Have a frying pan with a wire basket and arrange the pieces of meat or croquettes so that they will not touch each other. Plunge them in the fat, testing it first with a small piece of bread, which should brown in thirty seconds. When cooked, drain the meat over the hot fat; shake the basket and place the pieces on soft paper so that the fat may be absorbed.

Olive oil is best for frying; but as it is expensive for general use, various compounds such as cottolene, suetine, crisco, etc., may be used. These on the whole are better than lard, which is easily absorbed and therefore apt to make the food greasy. Suet and drippings are cheapest; but suet alone cools quickly and leaves a tallowy taste.

Dry the meat; roll it in fine bread crumbs; then dip it in beaten egg diluted with water; roll it in bread crumbs again and fry. The white of the egg hardens immediately if the fat is sufficiently hot and the fat cannot penetrate to the meat. Mix a little salt and pepper with the bread crumbs.

The Frying Process

Fried Oysters © 1906 Table Talk's Illustrated Cook Book

The process of frying is the truest culinary sense "boiling in fat or in oil." Fat is but oil modified, and oil is liquid fat; nevertheless the conditions of boiling in oil are altogether different, and the effects to a certain extent contrary to the mode of boiling in other liquids.

For frying, the fat usually registers from 300 to 360 degrees, while boiling oil is about three times as hot as boiling water. In consequence of this, if articles of food are plunged into boiling oil or fat, they offer the very opposite results to what they do in boiling liquid stock or water.

By the latter method, meat, vegetables, fish, etc., become soft and in some cases dissolved, they become solid boiled meats, etc., or are reduced to the condition of purée (pulp); while in frying they become firm, and ultimately brown on their outside and if left too long in boiling fat, they become black. Fat is incapable of dissolving the internal juices of frying food.

Issues Caused by Long Frying

Fried Fresh Codfish - New Hampshire Style © 1913 American Cookery

When anything becomes dry through long frying, the cause is that the continued heat of the fat drives out all the moisture in the state of vapor. It is not generally known that when burnt fat is eaten in any form it causes great trouble in the stomach, for soon after it enters the stomach, it produces butyric acid, which is the most unwholesome of all acids. When present in the stomach, a gas is formed which causes heartburn.

It is difficult to cook food in fat, namely, to fry it, because it ought to be made at least twice as hot as boiling water before it is fit for use. The point to which fat or oils may be heated varies, some burning much more readily than others.

About 350 to 400 degrees is a suitable temperature; it can be higher, it should sometimes be lower for things that need slow cooking, but it is usually better to begin at a high temperature and lower it afterwards.

To fry well, have a deep frying pan half full of fat so that whatever is to be cooked may be completely covered. This is not extravagant, as whatever fat remains can be strained, clarified and used again.

Frying is cooking by means of immersion in deep fat raised to a temperature of 350° to 400° F. For frying purposes olive oil, lard, beef drippings, cottolene, coto suet, and cocoanut butter are used. A combination of two-thirds lard and one-third beef suet (tried out and clarified) is better than lard alone.

Cottolene Vintage Ad © 1905 The N. K. Fairbank Company

Cottolene, coto suet, and cocoanut butter are economical, inasmuch as they may be heated to a high temperature without discoloring, therefore may be used for a larger number of fryings. Cod fat obtained from beef is often used by chefs for fryiug.

Great care should be taken in frying that fat is of the right temperature; otherwise food so cooked will absorb fat.

Nearly all foods which do not contain eggs are dipped in flour or crumbs, egg, and crumbs, before frying. The intense heat of fat hardens the albumen, thus forming a coating which prevents food from u soaking fat.”

Frying Warm(er) versus Cold Foods

When meat or fish is to be fried, it should be kept in a warm room for some time previous to cooking, and wiped as dry as possible. If cold, it decreases the temperature of the fat to such extent that a coating is not formed quickly enough to prevent fat from penetrating the food. The ebullition of fat is due to water found in food to be cooked.

Great care must be taken that too much is not put into the fat at one time, not only because it lowers the temperature of the fat, but because it causes it to bubble and go over the sides of the kettle. It is not fat that boils, but water which fat has received from food.

All fried food on removal from fat should be drained on brown paper.

Rules for Testing Fat for Frying.

- When the fat begins to smoke, drop in an inch only of bread from soft part of loaf, and if in forty seconds it is golden brown, the fat is then of right temperature for frying any cooked mixture.

- Use same test for uncooked mixtures, allowing one minute for bread to brown.

Many kinds of food may be fried in the same fat; new fat should be used for batter and dough mixtures, potatoes, and fishballs; after these, fish, meat, and croquettes. Fat should be frequently clarified.

Clarify Fat

To Clarify Fat. Melt fat, add raw potato cut in quarter-inch slices, and allo>v fat to heat gradually; when fat ceases to bubble and potatoes are well browned, strain through double cheesecloth, placed over wire strainer, into a pan. The potato absorbs any odors or gases, and collects to itself some of the sediment, remainder settling to bottom of kettle.

When small amount of fat is to be clarified, add to cold fat boiling water, stir vigorously, and set aside to cool; the fat will form a cake on top, which may be easily removed; on bottom of the cake will be found sediment, which may be readily scraped off with a knife.

Remnants of fat, either cooked or uncooked, should be saved and tried out, and w hen necessary clarified.

Shortening

Crsico Vintage Ad © 1921 Woman's Home Companion

Fat from beef, poultry, chicken, and pork, may be used for shortening or frying purposes; fat from mutton and smoked meats may be used for making hard and soft soap; fat removed from soup stock, the water in which corned beef has been cooked, and drippings from roast beef, may be tried out, clarified, and used for shortening or frying purposes.

To Try out Fat. Cut in small pieces and melt in top of a doable boiler; in this way it will require less watching than if placed in kettle at the back of range. Leaf lard is tried out in the same way; in cutting the leaf, remove membrane. After straining lard, that which remains may be salted, pressed, and eaten as a relish, and is called scraps.

Rules for Frying.—French or Wet Frying

This is cooking in a largo quantity of fat sufficient to cover the articles fried in it. Oil, lard, dripping, or fat rendered down, may be used for this purpose. Oil is considered the best, as it will rise to 600° without burning; other fats get over-heated after 400°, and therefore require greater care in using.

Success depends, almost entirely, on getting the fat to the right degree of heat. For ordinary frying the heat required is 345°. Unless this point is carefully attended to, total failure will be the result.

There are signs, however, by which anyone may easily tell when the fat is ready for use. It must be quite still, making no noise; noise, or bubbling, will be caused by the evaporation of moisture, or water in it.

The expression, “boiling lard,” or “boiling fat,” has been misleading to many cooks, who, not unnaturally, imagine that when the fat is bubbling, like boiling water, it is boiling and therefore at the right heat.

But boiling fat does not bubble, nor is the expression boiling correct. When fat has the appearance of boiling water, it is simply due, as already explained, to the presence of water in it, which must pass away by evaporation, before it can reach the required heat.

When it ceases to make any noise, and is quite still, it should be carefully watched; for very soon a pale blue vapor is seen rising, and then the fat is sufficiently hot.

If, from the position of the stove it is not easy to see this vapor, a piece of bread may be held in the fat as a test; if it begins to turn color, in about a quarter of a minute, the fat is ready. It should then be used without delay; since, when once hot enough it rapidly gets over-heated or burnt.

Fat is burning when the blue vapor becomes like smoke. Burnt fat has an unpleasant smell, and is apt to give a disagreeable taste to the articles fried in it.

Snowdrift Shortening Vintage Ad © 1920 Wesson Oil

With ordinary care fat need not get over-heated. Next to oil, fat rendered down (see Rendering down Fat) is best for the purpose. If strained after each time of using, and not allowed to burn, it will keep good for months, and may be used for fish, sweets, or savories, and no taste of anything previously fried in it will be given to the articles cooked. For this kind of frying, a Kitchener, or gas stove, is preferable to an open range.

All kinds of rissoles, croquettes, fillets and cutlets of fish, fritters, &c., should be fried in this manner, and should not bo darker than a golden brown. It is an advantage to use a frying-basket for all such things as are covered with egg and bread-crumbs; but fritters, or whatever is dipped in batter, should be dropped into the fat.

As they become so light that they rise to the top of it, when they are a pale color on the one side, they should be turned over to the other. Caro must be taken to drain everything after frying on kitchen paper, in order to remove any grease.

Utensils for Frying

A deep iron bowl with a bail, known as a Scotch bowl, a wire basket that fits loosely into the bowl, a long-handled fork or spoon, to hold the basket during frying and while the cooked articles are draining, a tin pan to set the basket on, and soft paper in a second pan for the final draining are the utensils that render frying a simple process. When a frying-basket is not accessible, a long-handled skimmer will do fairly well.

Table Talk: The American Authority upon Culinary Topics and Fashions of the Table, Vol. XXVII, 1912, A Series of Articles Published Throughout the Year. Published Monthly by The Arthur H. Crist Co., Cooperstown, NY. A Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Interests of American Housewives, Having special reference to the Improvement of the Table. Marion Harris Neil, Editor.

Fannie Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-school Cook Book, Revised Edition, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company (1912), p. 20-22