The Story of Tea - 1922

Tea Pots at the Lexington Hotel © 1913 American Cookery

The origin of tea as a beverage is shrouded in doubt. Some authorities believe that the plant is a native of China, while others are sure that India is its natural home.

The most we know is that the annals of ancient China tell of its use as a beverage by all classes of natives. The first knowledge of tea reached Europe early in the 16th century, and at that time it was sold at $25 to $50 a pound.

Tea has played an important part in the history of America, as every school child well knows. The story of the Boston Tea Party will be told as long as the American republic survives.

The American tea trade dates back to 1784, when the first American ship sailed for China. The success of this enterprise caused others to engage in the trade, and in 1785 two ships brought some 880,000 pounds of tea.

In 1786 over 1,000,000 pounds were brought here from China. The trade continued exclusively with China till 1868, when the first cargo of tea arrived from Japan.

The use of tea in America has grown with the population, so that in 1868 the importation reached nearly 38,000,000 pounds, and at present the people of the United States consume 100,000,000 pounds yearly.

The cultivation of tea is confined largely to countries or parts of countries in the Tropics, China, India, Ceylon, Japan, Formosa, Java, and Sumatra.

What Green and Black Teas Are

The generic classification of tea may be confined to green and black, though each of these may be said to cover hundreds of grades and qualities. Black tea—known to you as Ceylon, India, Java, orange pekoe, congou, English breakfast, etc.— is a fermented tea.

Green tea—that is, young hyson, pan-fired Japan. gunpowder—is unfermented. Oolong teas are semi-fermented. If the leaves of the tea plant are carried at once from the tea field to a place where heat can be applied to them, they are prevented from fermenting, and the result is a green tea.

If the leaves are allowed to ferment spontan eously for a few hours, the color changes from green to a copper color. If heat is then applied, fermentation is stopped, and black tea results. If the leaves are allowed to ferment for a short time only and then cured, oolong or semi-fermented tea is the product.

India, Ceylon, Java, and Sumatra specialize in black tea. Japan produces green tea. China manufactures black, green, and oolong teas, and Formosa sends us a semi-fermented or oolong tea.

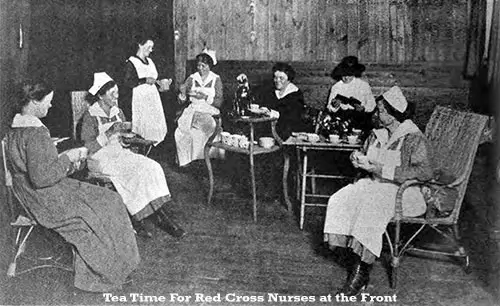

Tea Time for Red Cross Nurses at the Front © 1918 Tea and Coffee Trade Journal

Government Experts on Watch

When you buy tea at the corner grocery you perhaps never think of the care that has been exercised by your Uncle Sam to prevent you from getting an inferior or deleterious beverage.

The United States Department of Agriculture, of which the Tea Inspection Service is a part, and which also enforces the federal Food & Drug Act, has six tea examiners, one in each of the following ports of entry: New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Tacoma, and St. Paul. The supervising tea examiner at Washington directs their activities.

These seven men with their clerks and samplers are charged with guaranteeing the humblest citizen in the nation that not one ounce of tea out of the 100,000,000 pounds imported each year is below the standard set by the government.

The standard is set once each year by a Board of Tea Experts, who are recognized as leaders in the tea trade and are appointed by the secretary of Agriculture. Their session lasts usually one week and is held at New York. They establish a standard for each variety of tea.

A tea merchant who values his solvency can indulge in no happy-go-lucky shipment of tea into America, as is frequently done with other merchandise.

Every pound of tea he buys for shipment must be compared with the government standard before it leaves the country of export; otherwise he takes a long chance of its rejection upon arrival.

Nor are his risks at an end when the tea starts on its journey. Many things may happen on the way that will cause the rejection of tea that when it started was fully up to government standard.

A storm at sea may wash water into the hold of the vessel where the tea is stowed; a fire on ship board; in a mixed cargo the proximity of oil, bile, or other unctuous or fragrant merchandise, —any or all of these may so affect the tea as to cause its rejection in an American port.

If rejected, the importer may denature the tea, thus rendering it unfit for human consumption, and then dispose of it for chemical purposes, or he may export it to some other country—and there are a great many where the authorities are not so particular.

Testing the Imports

The importer of a cargo of tea must furnish the Tea Inspection Service with a list setting forth the different varieties and the number of chests of each. The tea examiner then decides the quantity of samples to be drawn.

This is done by boring a hole in the side of the chest and letting several ounces of the tea run out into a special sampling tin which has been labeled in advance.

A cork is then driven tightly into the hole in the tea chest to prevent the absorption of any extraneous odors by the tea. The sample is then taken to the examiner, who tests it and compares it with the standard, is accepted; if not, the cargo may be resampled and retested. If retesting develops a sub-standard tea, the cargo is rejected.

The importer then has the right to appeal from the action of the examiner to the Board of Tea Appeals. If this board confirms the action of the examiner, the tea must be destroyed, denatured, or exported forthwith. If this board overrules the examiner, the tea will be admitted.

As far as I know, the United States is the only country in the world that has a law of this kind. Few people know that the government insists that tea imported into this country be of good quality.

I remember reading a short time ago a tea advertisement which said, “All tea imported into the United States is pure. The government sees to that.” This is true. The average number of pounds that was denied admittance from 1913 to 1920 was 1,361,987 a year, or a total of nearly 11,000,000 pounds.

Tea may be rejected for any of the following reasons: If it is not equal to standard in quality; if it is colored or faced; if it contains too much dust or woody stems; if it has become damaged or tainted in any way.

Which Tea Is Best?

De Luxe Individual Tea Packet © 1922 Formosa Ooolong Tea

Here is a question that people ask me oftener than any other: “Which is the best tea?” I can answer it only by asking, “Which tea do you like best? Well, that is the best tea.”

There are so many varieties of tea and so many different grades and styles of each kind, that it is impossible for one not to like tea. You may not care a great deal for the tea you are drinking, but there are over 2,000 other teas for your consideration, and if you will experiment a little, you are sure to find one that will please you.

Do you like black tea, of rich and malty flavor? India, Ceylon, or Java will give you just what you desire. Perhaps you like the flavor of black tea, but think it rather thick and heavy? You can get a lighter liquor in these very same teas; or, if you think you would like a milder black tea, ask your tea man for a good grade of congou.

Then there are oolong teas. These may also be classified as black teas, though the flavor is entirely different from that of Ceylon, India, Java, and congou.

There is no better tea in the world than a high-grade Formosa oolong, and if you like a fragrant tea of delicate flavor you will no doubt be satisfied with it. China and Japan offer many varieties of green tea from which to choose, gunpowder, imperial, young hyson, pan-fired, basket-fired, natural-leaf, and many others.

Have a talk with your tea man, tell him what you think you want, ask his help, or have him get the information from the importer who supplies him. Demand the tea, you want and keep right on demanding it,

keeping in mind that tea is an economical drink. A good tea will yield 300 to 400 cups to the pound, and at that rate it would seem that almost anyone could afford the best.

How to Keep Tea in the Home

Don't ruin tea by leaving it exposed to air. People usually keep their tea in a pantry, where it comes into contact with other foodstuffs, and, If it be up to standard, it as it has great absorptive qualities, it will take up the flavor of nutmeg, pepper, flavoring extracts, etc.

A woman once asked if I could tell her why she was never able to get a good cup of tea at home. I asked her to let me see the tea she was using: She brought the package from her pantry, and I brewed a cup. I then asked where she kept her pepper.

Standing on the shelf right near the tea was a large can of it, and this had so affected the tea that it was hardly fit to drink. I suggested that she obtain a new package and that the tea be put into a mason jar, which makes an excellent container. She has since told me that from that day on she has not had a bit of trouble.

I am sometimes asked whether tea is injurious. I believe that a cup of tea properly made is a healthful, pleasant, and stimulating beverage. If you boil your tea or let the water stand on the leaves for a long time, and then consume eight or nine cups at a sitting, you will not do yourself a bit of good; but I feel sure that tea properly made can be taken three times a day with beneficial results.

When you are tired and worried, a cup of good tea has a wonderful soothing and stimulating effect for the manual worker, the brain worker, or for the tired housewife.

Tea With Lemon for Better Style © 1921 The Ladies Home Journal

How to Brew It

It is important that you prepare your tea properly. There is an art in brewing tea which every housewife has not mastered. The amount of tea to be used must of necessity depend upon individual taste. Some like it strong, and some weak. As an average suppose we say a teaspoonful to a cup.

The water must be boiling, otherwise the tea leaves will not open fully, and part of the strength and flavor will be lost. Tea should never be boiled, neither should the water stand in contact with the leaves for longer than five or six minutes.

Pour the liquor into another receptacle after it has stood about five minutes; or, better still, use a tea ball, and then all you have to do is to remove it when it has steeped long enough.

Some teapots are fitted with a container that can be removed, and you will find these convenient. Any method that will take the leaves out of the liquor will do.

After they have been removed, you may drink the tea at your leisure, for it will not get any stronger. I like a tea that has steeped only three to four minutes, and I use an aluminum strainer, put the tea into it, put the strainer across the top of the teapot, and pour boiling water through the strainer till the pot is full.

The body of the strainer will then be in the boiling water. After it has drawn for three or four minutes, I take the strainer out, and have a cup of tea that is just to my liking.

Use an earthenware teapot. Metal teapots, with the possible exception of silver and aluminum, are not the best for tea making.

Many people add milk or cream to their tea, and believe it adds to its flavor. Others like to add a few drops of lemon juice. I like the flavor of tea without any additions except a little sugar.

I believe that a little lemon in a good black tea, especially iced tea, makes a very pleasant drink: but, on the other hand, it seems to me that the addition of lemon juice to green or oolong tea destroys the flavor. This, however, is a matter of taste, and must be decided by the individual.

If you will follow these directions, I am sure you will always have a pleasant and invigorating drink, that will make you feel better, and do you good.

C. F. Hutchinson, “The Story of Tea,” in The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, , New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Co., Vol. 42, No. 7, July 1922, p. 50-51.

C. F. Hutchinson was a U.S. Tea Examiner, New York