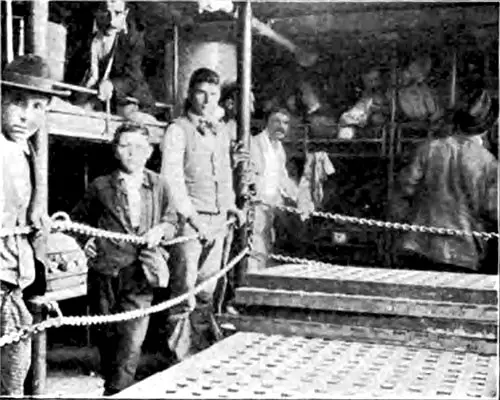

Steerage Conditions - Immigration Commission Report - 1911

Immigrants from Steerage on Deck of SS Frederich Der Grosse circa 1907. Bain Collection, Library of Congress # 2001704435. GGA Image ID # 145d3970fe

The Immigration Commission's report on steerage conditions, which was presented to Congress December 13, 1909, was based on information obtained by special agents of the Commission traveling as steerage passengers on 12 different transatlantic steamers, as well as on ships of every coastwise line carrying immigrants from one United States port to another.

There had never before been a thorough investigation of steerage conditions by national authority, but such superficial investigations as had been made, and the many nonofficial inquiries as well, had disclosed such evil and revolting conditions on some ships that the Commission determined upon an investigation sufficiently thorough in showing impartially just what conditions prevailed in the steerage.

It is, of course, correct that the old-time steerage with its inherent evils largely disappeared with the passing of the slow sailing vessel from the immigrant-carrying trade, but the Commission's investigation proved clearly that the "steerage" is still a fact on some ships, although on others it has been abolished.

Indeed, the investigation showed that both good and bad conditions might and do exist in immigrant quarters on the same ship; but, what is of more importance, it showed that there is no reason why the disgusting and demoralizing conditions which have commonly prevailed on immigrant ships should continue.

The complete report of the Commission upon this subject includes a detailed account of the experiences of an Immigration Commission agent in the steerage of three transatlantic ships, but for this summary, a more general description of conditions (Note 1) under immigrants are carried at sea will suffice.

Because the investigation was carried on during the year 1908, when, owing to the industrial depression, immigration was very light, the steerage was seen practically at its best.

Overcrowding, with all its concomitant evils, was absent. What the steerage is when travel is heavy, and all the compartments filled to their entire capacity can readily be understood from what was actually found.

In reading this report, then, let it be remembered that not extreme, but comparatively favorable, conditions are here depicted.

Transatlantic steamers may be classed in three general subdivisions by their provision for other than cabin passengers. These are vessels having the ordinary old-type steerage, those having the new-type steerage, and those having both.

To make clear the distinction among these subdivisions, a description of the two types of Steerage, old and new, will be given.

THE OLD-TYPE STEERAGE

The Men's Sleeping Quarters in Steerage, Showing Arrangement of Bunks and Baggage in Bed with Occupants. Leslie's Monthly Magazine, May 1904. GGA Image ID # 146270d558

The old-type steerage is the one whose horrors have been so often described. It is, unfortunately, still found in a majority of the vessels bringing immigrants to the United States.

It is still the typical steerage in which hundreds of thousands of immigrants form their first conceptions of our country and are prepared to receive their first impressions of it.

The universal human needs of space, air, food, sleep, and privacy are recognized to the degree now made compulsory by law. Beyond that, the persons carried are looked upon as so much freight, with mere transportation as their only due.

The sleeping quarters are large compartments, accommodating as many as 300, or more, persons each. For assignment to these, passengers are divided into three classes; namely, women without male escorts, men traveling alone, and families.

Each class is housed in a separate compartment, and the compartments are often in different parts of the vessel. It is generally possible to shut off all communication between them, though this is not always done.

The berths are in two tiers, with an interval of 2 feet and 6 inches of space above each. They consist of an iron framework containing a mattress, a pillow, or more often a life-preserver as a substitute, and a blanket. The mattress, and the pillow if there is one, is filled with straw or seaweed.

On some Lines, this is renewed every trip. Either colored gingham or coarse white canvas slips cover the mattress and pillow. A piece of iron piping placed at a height where it will separate the mattresses is the "partition" between berths. The blankets differ in weight, size, and material on the different lines.

On one line of steamers, where the blanket becomes the property of the Passenger on leaving, it is far from adequate in size and weight, even in the summer.

Generally, the passenger must retire almost fully dressed to keep warm. 'through the entire voyage, from seven to seventeen days, the berths receive no attention from the stewards.

The berth, 6 feet long and 2 feet wide and with 2 1/2 feet of space above it, is all the space to which the steerage passenger can assert a definite right.

To this 30 cubic feet of space, he must, in no small measure, confine himself. No area is designated for hand baggage. As practically every traveler has some bag or bundle, this must be kept in the berth. It may not even remain on the floor beneath.

There are no hooks on which to hang clothing. Almost everyone has some better clothes saved for disembarkation, and some wraps that are not worn all the time, and these must either be hung about the framework of the berth or stowed somewhere in it.

At least two large transportation lines furnish the steerage passengers eating utensils and require each one to retain these throughout the voyage.

As no repository for them is provided, a corner of the berth must serve that purpose. Towels and other toilet necessities, which each passenger must furnish for himself, claim more space in the already crowded berths.

The floors of these large compartments are generally of wood, but floors consisting of large sheets of iron were also found.

Sweeping is the only form of cleaning done. Sometimes the process is repeated several times a day. This is particularly true when the litter is the leavings of food sold to the passengers by the steward for his own profit.

No sick cans are furnished, and not even large receptacles for waste. The vomit of the seasick is often permitted to remain a long time before being removed. The doors, when iron, are continually damp and when of wood, they reek with foul odor because they are not washed.

The open deck available to the steerage is limited, and regular separable dining rooms are not included in the construction. The sleeping compartments must, therefore, be the constant abode of a majority of the passengers.

During days of sustained storm, when the unprotected open deck cannot be used at all, the berths and the passageways between them are the only places where the steerage passenger can spend his time.

When to this very limited space and much filth and stench is added with an inadequate means of ventilation, the result is almost unendurable. Its harmful effects on health and morals scarcely need be indicated.

Two 12-inch ventilator shafts are required for every 50 persons in every room, but the conditions here are abnormal, and these provisions do not suffice.

The air was found to be invariably bad, even in the higher enclosed decks where hatchways afford further means of ventilation. In many instances persons, after recovering from seasickness, continue to lie in their berths in a sort of stupor, due to breathing vitiated air.

Those passengers who make a practice of staying much on the open deck feel the contrast between the air out of doors and that in the compartments, and consequently find it unsuitable to remain below long at a time. In two steamers the open deck was always filled long before daylight by those who could no longer endure the foul air between decks.

Washrooms and lavatories, separate for men and women, are required by law, and this law also states that they shall be kept in a "clean and serviceable condition throughout the voyage."

The indifferent obedience to this provision is responsible for further uncomfortable and unhygienic conditions. The cheapest possible materials and construction of both washbasins and lavatories secure the smallest possible degree of convenience and make the maintenance of cleanliness extremely difficult where it is attempted at all.

The washbasins are invariably too few in number, and the rooms in which they are placed are so small as to admit only by crowding as many persons as there are basins.

The only provision for counteracting. all the dirt of this kind of travel is cold salt water, with sometimes a single faucet of warm water to an entire washroom. And in some cases, this faucet of warm water is at the same time the only provision for washing dishes.

Soap and towels are not furnished. Floors of both washrooms and water-closets are damp and often filthy until the last day of the voyage when they are cleaned in preparation for the inspection at the port of entry.

Regular dining rooms are not a part of the old type of steerage. Such tables and seats as the law says "shall be provided for the use of passengers at regular meals "are never sufficient to seat all the passengers, and no effort is made to do this by systematically repeated sittings. In some instances, the tables are small shelves along the wall of a sleeping compartment.

Sometimes plain boards set on wooden trestles and rough wooden benches placed in the passageways of sleeping compartments are considered a compliance with the law.

Again, when a compartment is only partly fall, the unoccupied space is called a dining room and is used by all the passengers in common, regardless of what- sex uses the rest of the compartment as sleeping quarters. (82401—vol. 2-11-2A)

When traffic is so light that some compartment is entirely unused, its berths are removed and stacked in one end and replaced by rough tables and benches.

This is the amplest provision of dining accommodations ever made in the old-type steerage, and occurs only when space is not needed for other more profitable use.

There are two systems of serving the food. In one instance the passengers, each carrying the crude eating utensils given him to use throughout the journey, pass in single file before the three or four stewards who are serving and each receives his rations.

Then he finds a place wherever he can to eat them, and later washes his dishes and finds a hiding place for them where they may be safe until the next meal.

Naturally, there is a rush to secure a place in line and afterward a scramble for the single warm-water faucet, which has to serve the needs of hundreds. Between the two, tables and seats are forgotten or they are deliberately deserted for the fresh air of the open deck.

Under the new system of serving, women and children are given the preference at such tables as there are, and the most essential eating utensils are placed by the stewards and are washed by them.

When the bell announces a meal, the stewards form in a line extending to the galley, and large tin pans, each containing the food for one table, are passed along until every table is supplied. This constitutes the table service.

The men passengers are even less favored. They are divided into groups of six. Each group receives two large tin pans and tin plates, cups, and cutlery enough for the six; also one ticket for the group.

Each man takes his turn in going with the ticket and the two large pans for the food for the group, and in washing and caring for the dishes afterward. They eat where they can, most frequently on the open deck. Stormy weather leaves no choice but the sleeping compartment.

The food may generally be described as fair in quality and sufficient in quantity, and yet it is neither; reasonably good materials are usually spoiled by being wretchedly prepared. Bread, potatoes, and meat, when not old leavings from the first and second galleys, form a fair substantial diet.

Coffee is invariably bad, and tea does not count as food with most immigrants. Vegetables, fruits, and pickles form an insignificant part of the diet and are generally of a very inferior quality.

The preparation, the manner of serving the food and disregard of the proportions of the several food elements required by the human body, make the food unsatisfying and therefore insufficient.

This defect and the monotony are relieved by purchases at the canteen by those whose capital will permit. Milk is supplied for small children.

Hospitals have long been recognized as indispensable, and so are specially provided in the construction of most passenger-carrying vessels. The equipment varies, but there are always berths and facilities for washing and a latrine closet at hand. A general aversion to using the hospitals freely is very apparent on some lines.

Seasickness does not qualify for admittance. Since this is the most prevalent ailment among the passengers, and not one thing is done for either the comfort or convenience of those suffering from it and confined to their berths, and since the hospitals are included in the space allotted to the use of steerage passengers, this denial of the hospital to the seasick seems an injustice.

On some Lines, the hospitals are freely used. A passenger ill in his berth receives only such attention as the mercy and sympathy of his fellow-travelers supply.

After what has already been said, it is scarcely necessary to consider the observance of the provision for the maintenance of order and cleanliness in the steerage quarters and among the steerage passengers separately.

Of what practical use could rules and rations by the captain or master be when their enforcement would be either impossible or without measurable result with the existing accommodations?

The open deck has always been decidedly inadequate in size. The amendment to section 1 of the passenger act of 1882, (see Note) which went into effect January 1, 1909, provides that henceforth this space shall be five superficial feet for every steerage passenger tarried.

On one steamer showers of cinders were a deterrent to the use of the open deck during several days. On another, a storm made the use of the open deck impossible during half the journey.

The only seats available were the machinery that filled much of the deck. Section 7 of the law of 1882, which excluded the crew from the compartments occupied by, the passengers except when ordered there in the performance of their duties, was found posted in more or less conspicuous places.

There was generally one copy in English and one in the language of the crew. It was never found in all the several languages of the passengers carried, although if passengers of one nationality should understand this regulation, it is equally important that all should.

Considering this old-type steerage as a whole, it is a congestion so intense, so injurious to health and morals, that there is nothing on land to equal it. That people live in it only temporarily is no justification for its existence.

The experience of an angle is enough to change bad standards of living to worse. It is abundant opportunity to weaken the body and implant their germs of disease to develop later. It is more than a physical and moral test; it is a strain. And surely it is not the introduction to American institutions that will tend to make them respected.

The common plea that better accommodations cannot be maintained because they would be beyond the appreciation of the emigrant and because they would leave too small a margin of profit, carries no weight in view of the fact that the desired kind of steerage already exists on some of the lines and is not conducted as a philanthropy or a charity.

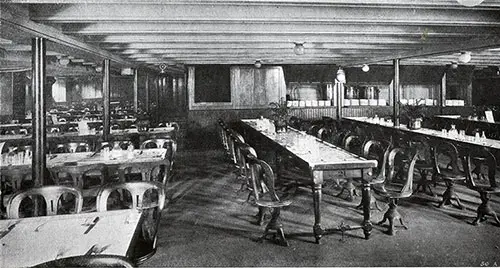

THE NEW-TYPE STEERAGE

Third Class / Steerage Dining Room. 1912 Brochure RMS Franconia and Laconia - Cunard Line. GGA Image ID # 11885a4643

Nothing is striking in what this new-type steerage furnishes. On general lines, it follows the plans of the accommodations for second-cabin passengers.

The one difference is that everything is simpler proportionately to the difference in the cost of passage. Unfortunately, the new type of steerage is to be found only on those lines that carry emigrants from the north of Europe. The number of these has become but a small percent of the total influx.

Competition was the most effective influence that led to the development of this improved type of steerage and established it on the lines where it now exists.

An existing practical division of the territory from which the several transportation lines or groups of such lines draw their steerage passengers lessens the possibility of competition as a force for the extension of the new type of steerage to all emigrant-carrying lines. The legislation, however, may complete what competition began.

The new-type steerage may again be subdivided into two classes. The better of new-type follows the plan of the second-cabin arrangements very closely; the other adheres in some respects to the old-type steerage. These resemblances are chiefly in the construction of berths and the location and equipment of dining rooms.

The two classes will not be considered separately, but the differences in them will be noted. The segregation of the sexes in the sleeping quarters is observed in accordance with the law much more carefully in the new type of steerage than in the other.

Women traveling without male escorts descend one hatchway to their part of the deck; men descend another, and families still another. Enclosed berths or staterooms secure further privacy.

The berths are sometimes precisely like those in the old-type steerage in construction and bedding, but the better class are built like cabin berths. The bedding is in some cases not clean, but the blankets are always ample.

Staterooms contain from two to eight berths. The floor space between is utilized for hand baggage. On some steamers, special provision is made beyond the end of the berths for luggage.

There are hooks for clothes, a seat, a mirror, and sometimes even a stationary washstand and individual towels are furnished. Openings below and above the partition walls permit circulation of air.

Lights near the ceiling in the passageways give light in the staterooms. In some instances, there is an electric bell within easy reach of both upper and lower berths which summons a steward or stewardess in case of need.

On some steamers, stewards are responsible for complete order in the staterooms. They make the berths and sweep or scrub floors as the occasion requires.

The most important thing is that the small rooms secure a higher degree of privacy and give seclusion to families. On most steamers, some large compartments remain. These are occupied by men passengers when traffic is heavy.

In spite of the less crowded conditions, the air is still bad. Steamers that are models in other respects are found to have air as foul as the worst. The lower the deck, the worse the air.

Though bearing no odors of filth, it is heavy and oppressive. It gives the general impression of not being changed as often as it should be.

Passengers who can go up on the open deck, and thus experience the difference between fresh air and that below, find it impossible to remain between decks long, even to sleep.

The use of the open deck generally begins very early in the morning. Where there are not stationary washstands in the staterooms, and their presence is still the exception and not the rule, lavatories separate for the two sexes are provided. These are generally of a size sufficient to accommodate comfortably, even more, persons than there are basins.

Roller towels are provided, and sometimes soap. The basins are of the size and shape most commonly used. They may be porcelain and cleaned by a steward, or they may be of a coarse metal and receive little care.

The water-closets are of the usual construction—convenient for use and not difficult to maintain in a serviceable condition. Floors are at all times clean and dry.

Objectionable odors are destroyed by disinfectants. Bath tubs and showers are occasionally provided, though their presence is seldom advertised among the passengers, and a fee is a prerequisite to their use.

Regular dining rooms appropriately equipped are included in the ship's construction. Between meals, these are used as general recreation rooms. A piano, a clock regulated daily, and a chart showing the ship's location at sea may be other evidence of consideration for the comfort of the passengers.

On older vessels the dining room occupies the center space of a deck, enclosed or entirely open, and with the gap between the staterooms opening directly into it; the tables and benches are of rough boards and movable.

The tables are covered for meals, and the heavy white porcelain dishes and good cutlery are placed, cleared away, and washed by stewards. The stewards also serve the food.

On the newer vessels, the dining rooms are even better. In were they resemble those of the second cabin. The tables and are substantially built and attached to the floor.

The entire width of a deck is occupied. This is sometimes divided into two rooms, one for men, the other for women and families. Between meals, men may use their side as a poking room. The floors are washed daily.

The desirability of eating meals served adequately at tables and away from the sight and odor of berths scarcely needs discussion. The dining rooms, moreover, increase the comfort of the passengers by providing some sheltered place, besides the sleeping quarters, in which pass the waking hours when exposed to the weather on the open deck becomes undesirable.

The food, on the whole, is abundant and when properly prepared wholesome. It seldom requires action from private stores or by purchase from the canteen.

Several complaints against the food are that poor preparation often spoils suitable material; that there is no variety and that the food lacks taste. But there were steamers found where not one of these charges applied.

Little children receive all necessary milk. Beef tea and gruel are sometimes served to those who for the time being can not partake of the usual food.

Hospitals were found in accordance with the legal requirements. On the steamers examined there was little occasion for their use. The steerage accommodations were conducive to health, and those who were seasick received all necessary attention in their berths.

With the striking difference in living standards between old and new types of steerage goes a vast difference in discipline, service, and general attitude toward the passengers.

One line is now perhaps in a state of transition from the old to the new type of steerage. It has both on some of its steamers. The emigrants carried in its two steerages, however, are not radically different in any way.

The replacement of sails by steam, with the consequent shortening of the ocean voyage, has practically eliminated the former abnormally high death rate at sea.

Many of the evils of ocean travel still exist, but they are not long enough continued to produce death. At present, a death on a steamer is the exception and not the rule.

Contagious disease may and does sometimes break out and bring death to some. There are also other instances of death from natural causes are rare and call for no special study or alarm.

The inspection of the steerage quarters by a customs official at our ports of entry to ascertain if all the legal requirements have been observed is, and in the very nature of things must be, merely perfunctory.

The inspector sees the steerage as it is after being prepared for his approval, and not as it was when in actual use. He does not know enough about the plan of the vessel to make his own inspection, and so he only sees what the steerage steward shows him.

The time devoted to the inspection suffices only for a passing glance at the steerage and the method employed does not tend to give any real information, much less to disclose any violations.

These, then, are the forms of steerage that exist at present. The evils and advantages of such are not far to seek. The remedies for such atrocities as now exist are known and proven, but it remains to make them compulsory where they have not been voluntarily adopted.

THE COASTWISE TRAFFIC

A. certain percentage of the immigrants who are distributed from New York City and other points travel toward their ultimate destination on smaller steamship lines in the coastwise trade. There seems to be no attention whatever paid to the accommodations for, or care of, immigrants on these ships.

On one steamer investigated it was found that steerage passengers were carried in a freight compartment, separated from the rest of the vessel only by canvas strips and that in this compartment the immigrants were not provided with mattresses or bedding.

There was practically no separation between the women and the men. On this boat, other passengers who pay the same price as do the immigrants have regular berths with mattresses and pillows, and a dining room is provided for their use. There is also separation of the sexes.

The negroes who patronize this line are quartered in this compartment and receive for the same price much better treatment than do the immigrants. This Line has carried as many as 200 immigrants on one trip in these freight compartments.

On another line, which has accommodations in its ordinary boats for about 50 immigrants, the immigrants can obtain food such as is served to the crew, but the berths are in three tiers, instead of two as on the transatlantic boats. The immigrants are also allowed the freedom of the lower forward deck.

An investigator's description of the hardships of the immigrants on one Hudson River boat is as follows :

Forward of the freight, in the extreme bow of the boat, is an open space. I saw immigrants lying on the Boor, also on benches, and some were sleeping on coils of rope, in some cases using their own baggage for headrests.

Conditions on the other line from New York to Albany were found to be similar, though in neither case was there any excuse for the crowding, as there was plenty of room on the boats.

Of a vessel in the coastwise trade, an investigator's notes read as follows: There was no attempt to separate the men from the women, and upon going into the sleeping quarters I found the women and men in all states of dress and undress (mostly the latter). Hot nights they slept on deck.

Sunday, at midnight, some man crept into the Polish woman's bunk and attempted an assault, but her cries drove him off.

Monday night about the same time, presumably the same man, now acknowledged to be a member of the crew—this information I obtained by talking to members of the crew—attempted, and perhaps succeeded, in assaulting the same woman. The captain started an investigation, but what came of it I was unable to learn, as the matter was hushed up.

It is fair to state that this charge was taken up by the proper authorities, but that no further evidence could be obtained. The quarters of that particular boat were clean and well kept and the food fair.

It is satisfactory to learn that upon the steamers of the Panama Railroad and Steamship Line, practically owned and operated by the United States Government, the conditions and discipline were found to be good, the only complaint being as to the food, which was said to be of very poor quality and of very scanty allowance on one of the boats.

The general comment to make concerning this class of transportation seems to be that the welfare of the immigrant is left entirely to the companies. If the line is humane and progressive, the immigrants are well treated. If it is not, the immigrants suffer accordingly. In all probability, the condition of the immigrants on these ships could be made much better by the enforcement of existing statutes.

Note 1: See Steerage Legislation, 1819-1908. Reports of the Immigration Commission, vol. 40. (8. Doe. No. 661, 61st Cong., 3d. sess.)

Abstract of Reports of the Immigration Commission, Volume II, 1911, Pages 296-303