New York Harbor - Pre World War II

The geographical conditions that made New York the logical gateway of this country, by reason of its great expanse of waterfront, favorable tide conditions, deep channels, and ready access to the ocean, caused a growth that has no parallel in history.

The Statue of Liberty, "Liberty Enlightening the World," The World-Famous Bartholdi Statue In The Upper Bay of New York on Bedloes Island, was presented to The United States by The Republic of France. GGA Image ID # 142846e8aa

Proposed Reorganization of the Port of New York (1921)

AFTER several years of study of future needs. Of the Port of New York, the New York, New Jersey Port & Harbor Development Commission -created in 1917 by the legislatures of the two States transmitted a most comprehensive plan for the future development of the Port to the Governors of New York and of New Jersey.

The scale of the transportation operations and the escalating burden of congestion and terminal costs underscore the need for immediate correction. This is a pressing issue that cannot be ignored.

The physical geography of the Port presents problems not created elsewhere, the diversity of its interests and activities, and its very bigness. So that the work may be carried on with continuity of policy and effort, the Commission urges the creation of a unified Port District and a continuing port authority with broad powers and jurisdiction over the entire Port District utilizing a compact or agreement between the State of New York and New Jersey.

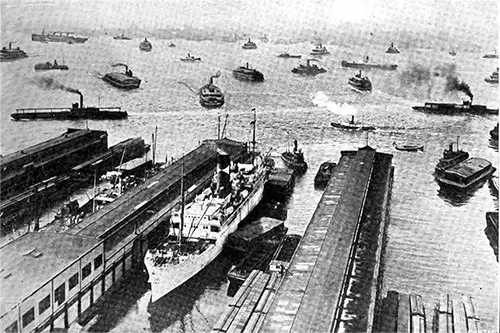

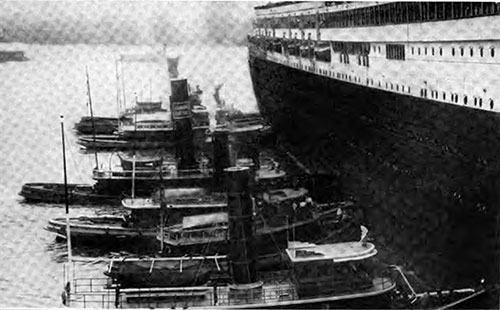

View of the Hudson River From the West Side of Manhattan Showing the Crowded Condition of Shipping, Which Will Be Greatly Diminished When the Vehicular Tunnel Is Completed. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 14285279b4

The Commission believes that rail lines should be brought to the tidal waters wherever feasible throughout the Port District, which is held to extend from Jamaica Bay to Newark and from Perth Amboy to Irvington on the Hudson. This would ensure efficient and economical coordination of rail and water service.

This is to be accomplished by a system of inner and outer beltline railroads on the harbor's New Jersey and New York sides, connecting all trunk lines and having numerous spurs to the various waterfronts.

Such lines, developed in such sequence as further study would determine, would provide for commercial and industrial development under the most favorable circumstances and expand domestic and foreign trade throughout the Port.

Every part of the Port except Manhattan will have standard freight rail service without breaking bulk. In Manhattan, the Commission found that a standard railroad was not feasible.

Therefore, it proposes an underground "automatic-electric system," an entirely new form of conveyor railroad that will serve the nine New Jersey trunk lines and the New York roads. It will carry freight on short trains of special cars moving without locomotives or train operators and running between terminals in Manhattan and joint yards away from the congestion.

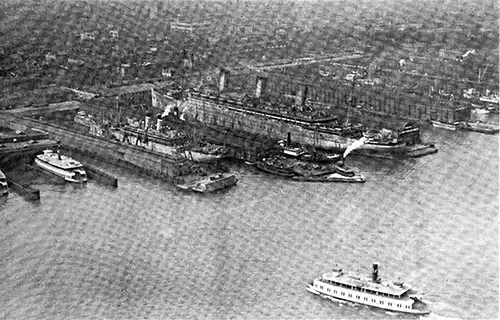

Plans 34 to 38 North River, Just Above Canal Street, Manhattan, Soon to Be Replaced With Longer and Wider Two-Story Piers With Wider Slips Between Them. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142885e43c

Two stages of the automatic-electric development are proposed. The first, linking the New York Central and New Jersey railroads through a loop from a joint yard in New Jersey and a spur to the New York Central's 60th St. yard, will provide equal service from each of the ten railroads at twelve union terminals in lower Manhattan.

The second is bringing the New Haven and Long Island Railroads into the system through a second joint yard near Wards and Randalls Islands, which the New York Central will also reach by additional tracks along the Harlem River and providing additional lines and stations in upper Manhattan, will give all parts of Manhattan universal rail service.

The automatic-electric system, with its terminals all set well back from the waterfront, will release the present railroad pier stations for steamship service and the Marginal Way for supporting warehouses, will eliminate the present congestion of trucks on West Street and the Marginal Way, and will place well-distributed union terminals much nearer the shippers and consignees, thereby greatly reducing the length of haul and street congestion in Manhattan for both inbound and outbound freight.

Fine View of the Battery Taken From About 900 Feet Altitude. Battery Park in the Foreground. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1428f8dcf8

The foregoing new facilities are expected to reduce the car-float and railroad lighterage movement in the harbor materially, but much will still remain. This the Commission would consolidate into joint operation from a few new railroad terminals at convenient points.

This improved railroad-terminal system is regarded as the backbone of rational port development, and it constitutes the physical plan which, together with a compact between the two States to make the plan effective, the Commission urges for formal adoption.

Cunard Line Piers 52 and 53 North River, Part of the “Chelsea District," are the Most Modern and Finest of New York's Piers. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1429089999

In furtherance of that rational development, the Commission recommends, among other things:

- Reorganization will be made with wider piers, slips, and more warehouse facilities in Manhattan and other congested waterfronts.

- Dredging of channels to every part of the Port's waterfront in keeping with the volume and character of the waterborne commerce seeking to use them, and removal or modification of bridges obstructing the channels.

- Provision of suitable highway access to every part of the Port's waterfront.

- Construction of additional terminals for the New York Barge Canal.

- Wide installation of judiciously selected freight-handling machinery.

- Creation of bunker facilities and fuel reserves for steamships.

- Erection of grain elevators for joint use of New Jersey railroads and New York barge canal at a southern terminus of the outer belt line and Piermont, and early completion of the barge canal elevator authorized at Gowanus Bay.

- Zoning of steamship terminals by trade routes as far as practicable.

- Establishment of free ports in the Port District.

- Obtaining of immediate partial relief from present oppressive terminal conditions through

- Consolidation of marine equipment and service, and

- Inauguration of voluntary store-door delivery by an organized motor truck medium.

The Commission does not consider an abundance of machinery a cure-all. Tractors and trailers to move the goods on the pier are held to be as important as cranes to transfer them over the ship's side, but neither is of much value if warehouse space is not available to relieve the wharf shed of storage duty.

While it will take several years to build and implement the automatic-electric and belt-line systems, the Commission proposes two steps for immediate partial relief. One is the consolidation of railroad marine equipment into a single fleet jointly operated; the other is the inauguration of "voluntary store-door delivery."

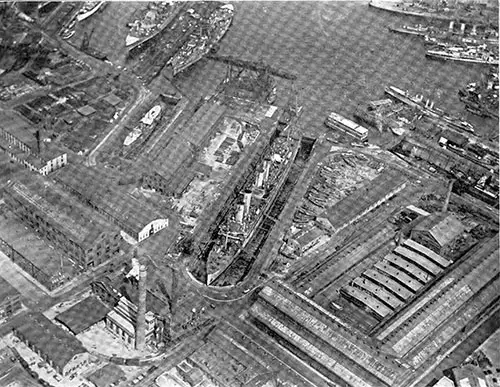

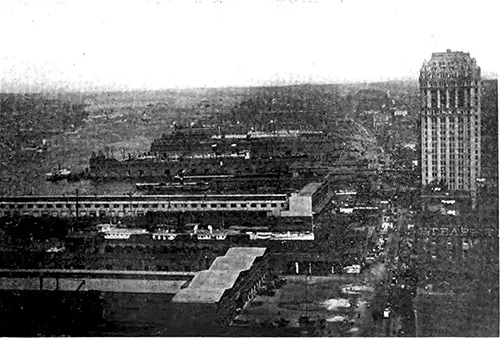

New York Central Railroad's Yards and Piers at 66th Street, North River, Manhattan. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1429192530

The Port of New York: An Overview of the Operations and Problems (1921)

This is from a paper read before the New York Chapter, American Society of Civil Engineers, by B. F. Cresson, Jr., Consulting Engineer to the New York, New Jersey Port & Harbor Development Commission.

Many phases of the New York port problem have been under public discussion since the port attained its pre-eminence. The geographical conditions made New York the logical gateway of this country because of its great expanse of waterfront, favorable tide conditions, deep channels, and ready access to the ocean, causing growth that has no parallel in history. New York has been an easy and cheap port through which to pass commerce and, with its natural facilities, has grown without the necessity of careful planning until the very volume of its business is choking it.

In recent years, this condition has begun to be appreciated. For the past decade, the necessity has been felt for a reorganization along administrative and physical lines so that the increase in commerce flowing through the port may be appropriately addressed and its railroad lines and steamship service brought into an economic whole.

New York has become the focal point of practically all transcontinental railroad lines; coastwise lines and ports connect those not reaching it directly with their rails. It is an excellent port for liner steamship service. New York is pre-eminently the world's port; its hinterland is the United States, and it is the banking and commercial metropolis of the New World.

Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad’s Ferry Slips, Foot West 23rd Street, New York City. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1429b86889

GEOGRAPHY OF THE PORT

New York, taking the whole port district, is unique among ports in that it lies within two states; the State line between New York and New Jersey passes down the Hudson River, New York Bay, the Kills and Raritan Bay, separating the port as far as legislative and political lines are concerned into two separate parts.

This separation, however, is solely a political and legislative one, as neither portion could operate without the other, and the port's future depends on the cooperation of all parts of the port and the organization of the port into one administrative and operative unit.

On the easterly side of the port, there is the City of New York, comprising the boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, and Richmond. This single political unit has a population of some 5,900,000; other important communities, such as Yonkers, lie in the easterly part of the Port District.

On the west side of the port are many independent municipalities; important cities include Newark, Jersey City, Hoboken, Bayonne, Elizabeth, Perth Amboy, Paterson, and Passaic. In the westerly portion of the port, the population is some 2,100,000, making the total population of the Metropolitan District at the Port of New York some 8,000,000 persons.

The convenient waterways within the port are among its most important assets-the Hudson and East Rivers, New York Bay, Newark Bay, Jamaica Bay, the Arthur Kills and Kill van Kull, Long Island Sound and the Harlem River, Flushing Bay and Raritan Bay, the Hackensack and Passaic Rivers and many of the waterways and bays give the port a waterfront of some 800 miles-all of which should properly be considered to be in the Port of New York District.

While the most available waterfront at the port has been taken up and developed, great sections of the waterfront remain undeveloped and available for use as commercial or industrial frontage. The statement so often made that New York is developed to the fullest possible extent of its waterfront is untrue.

The Steamship Leviathan, at the U. S. Army Base at Hoboken, NJ. The Leviathan Was Formerly the German Steamer Vaderland. She Is the Largest Ship in the World and Is at Present Laid Up. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 1429d2e2c1

ADMINISTRATION OF THE PORT

The government of New York City's waterfront is under the Dock Commissioner, the Board of Estimate and Apportionment, and the Commissioners of the Sinking Fund of the City. New York has had jurisdiction over its waterfront since 1871 and has invested more than $150,000,000 in building docks, piers, and harbor facilities. There is no continuity of administration in the city; each municipal election means a change in city government and federal policy and in developing and administrating the city's waterfront.

In the New Jersey portion of the port, the jurisdiction over the waterfront is divided between perhaps forty municipalities. There is no general control over the waterfront save only that exercised by the New Jersey State Board of Commerce and Navigation, which acts as trustee for the lands of the State lying below the high water line and is clothed with power to pass on all plans for public or private development on navigable waters within or bounding the State.

The condition leaves the port's waterfront without any central authority having jurisdiction and power to lay out and carry out or cause any general port plan to be carried out.

Brooklyn Bridge, Spanning the East River, Taken From Brooklyn Shore. Municipal Building at City Hall, Manhattan, in Background, September 16, 1920. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142a0d41d9

A PORT OF INDIVIDUAL ENDEAVOR

It is fair to say that given the volume of business that passes through the port, the various parts of the port and the carriers themselves have gone to unmatched lengths to provide facilities. But there has been no general comprehensive plan of development; New York, as well as various New Jersey Communities, have prepared plans for their individual development; commercial organizations, transportation agencies, and individuals have prepared plans, but they have, for the most part, been made to meet the particular local needs and have failed for the most part to reach the full consideration of the problem as a whole. There have been local plans to meet local situations within the Port District.

New York has tried to develop and operate as an individual part of the port, and so has New Jersey. The result has been an effort to create a number of individual ports within the district, which must be considered the Port of New York and planned as such, with each section put to its best use as part of a great financial, commercial, and industrial whole.

The same individualistic situation exists among the railroads entering the port. In the westerly or New Jersey section of the port are the railroads of the West Shore, Lackawanna, Erie, Pennsylvania, Lehigh Valley, Central of New Jersey, Ontario & Western, and Susquehanna & Western railroads, each except the latter two having its own separate break-up yards, approaches to the waterfront, waterfront yards and facilities, and marine equipment.

In the New York section of the port are the New York Central, the New Haven, the Long Island, and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroads. One has its principal freight terminal in Manhattan, another in the Bronx, another in Long Island, and the fourth in Staten Island or the Borough of Richmond. Each of these lines has its own separate and independent terminal facilities.

The terminals of the steamship lines are also primarily individual. The principal lines build or lease long-term piers for their personal use without the possibility of them being utilized by other ships or carriers should the conditions arise, rendering that advantageous except with the sanction of the steamship line in possession.

The railroads, private lighterage companies, some steamship lines, and several private terminal companies conduct individual operations in lighterage movements about the harbor waters.

Trucking also lacks coordination, except that recently, a large trucking combination was formed and is seeking to reduce costs and delays by inaugurating some sort of trucking or drayage system.

Instead of being correctly along the waterfronts or at the railroad terminals, the warehouses are scattered throughout the district without any particular relation to each other or the water or land carriers.

Some terminal companies within the port have organized and constructed along lines of joint operation performing a uniform service, and these companies have shown in their operations that economies can only be secured through a cooperative service in transportation, warehousing, and industrial facilities.

In many other respects, the individualistic character of operations at the Port of New York is shown, and it appears clear that a machine as large as the Port of New York cannot properly function except through the coordination of its parts. The coordination must be administrative, physical, and operative, and the very fact of the division of the port by political lines, of the cutting up of the waterfront and its supporting backland into private units, must be apparent to all students of port problems and city problems. This individuality must be set aside to benefit the communities and the port.

View of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Taken From the Air. GGA Image ID # 142a3af9e9

THE LAYOUT OF THE PORT

The principal railroads reach the port on the New Jersey side. The railroad rate for most commodities and most destinations covers delivery within what is known as free lighterage limits, which now embraces the active commercial frontage of the port; this rate applies to piers in New York and Brooklyn, as well as to piers in Hoboken and Jersey City, and as a result of this flat rate and the greater initiative and progressiveness of New York most of the steamship piers have been built in the New York part of the Port. New Jersey's frontage is devoted chiefly to railroad and industrial occupation, while New York's is mainly commercial.

The principal passenger steamship lines dock in Manhattan, the freighters in Brooklyn and Staten Island, the coastwise and New England lines in Manhattan, but perhaps 80 percent of the railroad business for the support of New York's local business and needs and the foreign and coastwise commerce of the port reaches and leaves the harbor by way of the New Jersey railroads.

The industrial development of Queens and the Bronx has been held back by the lack of quick and convenient access to the port's principal railroads. New piers are under construction by New York and Staten Island, and the steamship uses of the New Jersey frontage, now mostly limited to the piers at Hoboken, are to be added to by a major installation, as represented by the projected Cunard Terminal at Weehawken.

There are no rail connections for freight service between the New Jersey and New York sides of the Port.

Striking View of Battery Park, West Street, the Beginning of the North River Piers, and the Great Office Buildings at the Extremely Southerly End of Manhattan Island. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142a5b933d

THE RAILROAD PROBLEM

New York is reached by the rails of the principal transcontinental railroads, and each conducts its operations.

The general method of conducting inbound business is as follows: Break-up yards are located back from the waterfront, where trains are received, and cars are dispatched to the waterfront to be delivered to pier stations or their contents placed into lighters for delivery to steamships or to piers, or the cars may be transferred either by rail or car float to other rail lines and pass through the port district on their way to different destinations.

The operations are many and various, and the delays in goods and cars and the cost of the operations have been said to be very significant. However, the significance of these delays and costs at present is unknown.

THE MACHINERY PROBLEM

Pier cranes are not used to any extent in loading or unloading ships in New York, but there is a large fleet of cranes at the port that are used principally in loading and unloading barges at railroad piers.

New York has been accused of being deficient in modern freight-handling machinery. The general method of handling steamship freight at New York is in use at practically every large port of the world, and the operation, which is called "burtoning," is well-known and understood by shipping men, stevedores, and longshoremen.

The great number of cranes at foreign ports has been cited as the reason why those ports are cheaper and quicker than New York. Still, it is not certain that the wholesale provision of pier cranes can more economically handle the general class of cargo handled in New York. These cranes represent a significant investment, and their overhead and carrying charges would run into large amounts when unused.

Every ship is equipped with cargo masts and winches and must be so equipped to trade at ports where pier machinery does not exist. It may be admitted, however, that with suitable cranes located on suitable piers, properly designed and handling certain general cargoes, economies can be affected in the handling of freight and greater speed attained; one of the most important functions that machinery could perform would be to lessen the idle time of the ship at ports as the ship is earning only when it is traveling and every day in port that can be eliminated, even though the handling of freight may be slightly more expensive, will be of advantage to the ship and the port.

While cranes may not be the cure-all in New York, they will be a valuable part of the port's future equipment, and there is little doubt that more machinery within the piers is also needed. The various forms of conveyors, the gasoline or electrically driven tractor, the storage battery load-carrying truck, and the wheeled trailers have all been tested in operation and suggest economies both in time and cost. They are now mainly being installed at piers in New York and throughout the country.

View of the East River Below the Brooklyn Bridge. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142a66152a

THE WAREHOUSE PROBLEM

In New York, as well as at most ports in the United States, where facilities have been provided either by public bodies, railroads, or steamships, the terminals constructed have been deficient in warehousing and storage accommodations. Warehousing and storage are not directly the business of the public authorities, railroad companies, or steamship lines.

Instead, it is considered a separate business, and the result has been that It is mainly so in New York that the waterfront terminals are limited in their operation by a lack of facilities for the storage of freight, which is subsequently destined for 'either railroad or steamship movement. The result is that piers and railroad terminals are clogged with slow-moving freight, the ship's turnaround has been slowed, and railroad cars have been held as cargo storage.

The warehousing problem in New York is a very important one. Adequate warehousing adjacent and convenient to the waterfront could speed up ship turnarounds and free railroad rolling stock for transporting goods.

THE LIGHTERAGE PROBLEM

There is a vast lighterage movement about the port, estimated at up to 60.000.000 tons per year, conducted by railroad, steamship, terminal, and private lighterage companies.

Consolidating equipment and unifying operations could increase efficiency in the use of lighterage equipment, and this is a subject worthy of the most careful study and analysis in connection with a more unified operation at the port.

Ellis Island, Upper Bay of New York. U. S. Immigration Station. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142a840a64

OTHER PROBLEMS

Many other subjects make up the New York port problem and must be studied and understood to determine the port's future policy. The place to begin solving the problem of the world's greatest port is in the district's administration. The Joint Commission has already recommended the legislative enactment of a treaty binding together all parts of the Port District to be administered by a Port Authority.

Under this proposed treaty, the municipalities are adequately protected in their investments and facilities. No public credit is to be pledged for the development of future facilities, but merely the creation of a central body with sufficient authority and power to encourage private or public initiative to construct modern terminals as part of an organic whole.

Another View of the Battery, the Extreme Southerly Point of Manhattan. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142abf7bcf

It will form a medium under which funds can be raised without respect to the debt limit or the borrowing capacity of any of the Port District's component parts. It will have local interest, the port in general, and the whole country's commerce. Neither New York nor New Jersey can work out the best plan for the port by itself.

New York's problem is not local. Under normal conditions, it is half of the foreign commerce of the United States. It has in its immediate surroundings the greatest concentration of population and industry on the American continent, and as far as the port facilities are concerned, they must be not only for local benefit but for the benefit of the nation; as such, they must be removed from the strife of political manipulations and jealousies and placed where they belong under a jurisdiction that will spread beyond political subdivisions and will resolve the many individual interests into an administration working along business and economic lines.

There is a danger that unless the component parts of the Port cease wrangling and consider developing the port as a business entity, the Federal Government may step in and change the port's control from local to national.

Docking the German Ocean Liner SS Imperator in the North River. Port of New York, 1920. GGA Image ID # 142b304e72

It seems likely that such a situation, which would indeed be affected by political changes and by the jealousies of other ports and sections of the country, would not solve the problem so well as if the control and administration of the port were retained within the Port District where there is local knowledge and local pride, and under which it is probable that the best results could be achieved, not only for the port itself but for the entire nation.

The magnitude of the business at the Port of New York is so great, and the problems involved in operating the port are so numerous and complex that no physical plan of reorganization or operation can be effected unless the factors are ascertained and studied in detail and completeness and unless it is supported by economic proof of soundness.

New York, The Greatest Port in the World (1907)

Editorial Note. We are indebted to Broadway Magazine for the plates from which this most interesting article is printed. The article clearly portrays so many interesting features of New York City that we believe even New Yorkers themselves will find it as instructive as it is interesting—and we are sure that out-of-town readers will heartily welcome its reproduction here.

The New Customs House, New York. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142bf1f1a2

Kurd and Polack and Lett and Hun, Wallachian gypsies in their red sashes, strange people babbling a hundred languages, cargoes of spice from the Indies, sugar and coffee and ivory from the hot, lazy ports to the south, teas from China, milk from Denmark, rugs and drugs and silks from Singapore, fully one hundred million dollars worth of merchandise a month — all cast in heterogeneous confusion and tumult by a thousand ships into that hungry, eager mouth, the port of New York.

As warships, heavy with menace, steam slowly up the Narrows, they are joined by a myriad of vessels from all corners of the globe. Ferry-boats splash their way across river and harbor, while tugs ply crisscross like clucking, crazy hens in the choppy waters, adding to the bustling activity at the port.

A string of freight cars, ten strings, fifty strings, go floating by. A big liner, black with travelers, docks at its North River pier; oyster boats bob in the Gansevoort Market basin. Massachusetts fishermen in the East River cluster about the Fulton Street slip; coastwise steamers back away from their moorings and float outward. There, on the Brooklyn shore, the greatest warehouses in the world welcome the commercial booty of the earth—thirty million tons of it a year.

Wheat from the great Western prairies moves through these Narrows to supply the whole world with energy, cattle by the tens of thousands, and provisions by the tons! Oil from the Texas and Kansas fields, bound for London and Amsterdam; machinery for digging ditches in Arabia and Panama; typewriters for Persia; phonographs for the idle lords of Mozambique; cash registers for the Boers; threshing machines for Cape Town. Here is the sally port of the American invasion.

For this reason, New York is the greatest port in the world. More than twice as many vessels clear the port of London, to be sure — one every fourteen minutes as against one every half-hour for New York, but the average cargo value is only $47,242, whereas that of New York is $92,307.

Luggage In the Hands of The Inspectors. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142c3132a9

In point of tonnage, New York exceeds London by one million. This is due to a difference in the character of the ports that must be borne in mind when comparing them. London is England's one commercial center, and aside from Liverpool, it is only an excellent place for export and import.

It also practically has a monopoly on the coastwise trade of the kingdom, for almost all manufactured articles come to London either for export or distribution to other parts of the kingdom. Cotton goods are shipped by water from Birmingham to London; from London, they are shipped by water to different parts of England, Ireland, and Scotland or foreign ports.

On the other hand, New York is not the commercial center of America. When the manufacturer of shoes in Boston sends his goods to Baltimore, he either sends them by rail or vessel directly, without entering New York. If he wants to send his goods to France or Germany, he sends them from the port of Boston. The chief ports of the Atlantic seacoast, New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, Norfolk, Philadelphia, and Boston, engaged in coastwise and foreign trade in the entire independence of New York.

Ellis Island, The Receiving Station for Immigrants. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142c36d578

Less than twenty-eight percent of New York's tonnage is represented in coastwise trade, whereas fully fifty percent of London's, is coastwise. In other words, of London's commerce, amounting to $1,370,000,000 annually, only $685,000,000 represents foreign trade, whereas, of New York's $1,200,000,000 annual commerce, $864,000,000 represents foreign trade or an actual excess over London of $179,000,000.

To accommodate this enormous trade, New York has four hundred and four miles of improved water frontage: four hundred and four miles of docks. This is half the distance between New York and Chicago. London has less than two hundred miles of similar water frontage; Liverpool has less than one hundred miles, while Hamburg, Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Havre have each less than Liverpool. Practically all the available water frontage of these foreign ports has been absorbed by their docks, while New York has improved only a little over one-half of its available shore. When all the available coastline is improved, as it must be rapidly, it will measure nearly as many miles as lie between the Atlantic seaboard and the Mississippi River.

First, seriously considered improvements should be made in Jamaica Bay, east of Coney, on Long Island—six hours nearer New York than any other available point outside the immediate harbor. The long channel trip would be avoided, the route to the sea would be shorter and more direct, and more than enough time would be saved to make the train trip to Manhattan inconsiderable.

Improved railroad facilities, by tunnels under the city and rivers, and the tremendous railroad development of western Long Island, already underway, make Jamaica Bay as near the city's center as South Brooklyn or Jersey. With these improved facilities, passengers and freight can be carried directly through or about the city to or from any portion of the North American continent.

Twenty years from now, tourists to Europe may cross the continent and never leave their cars until the train draws up on a Jamaica Bay dock. The saving of time in the mail is of even greater importance to the commercial world. With four-day boats, daily mails, and quick transmission through the post office, the time now taken for a letter mailed in London to a New York address will be reduced by half.

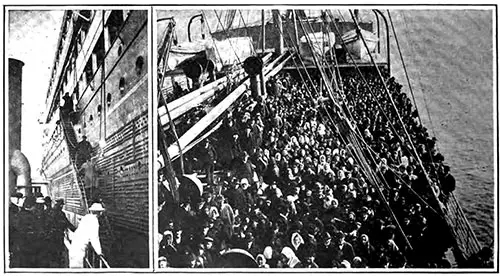

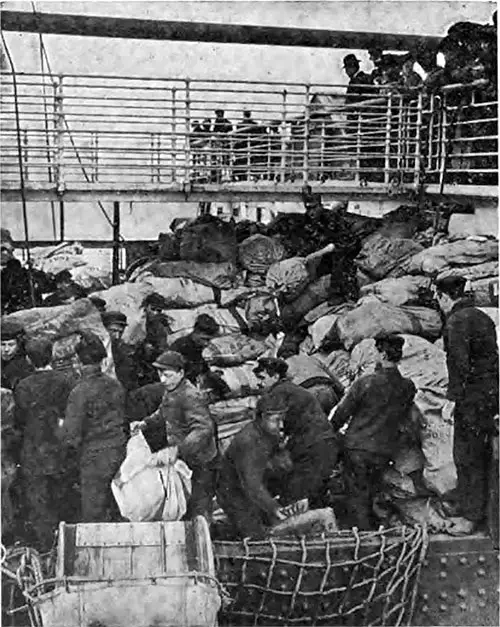

Come Aboard (left) and a Typical Crowd of Immigrants. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142d30967b

A year ago, Mayor McClellan, cooperating with the city's business organizations, appointed a commission to examine the feasibility of the Jamaica Bay project and suggest plans for its realization.

The Jamaica Bay Improvement Commission has recommended purchasing 9,000 acres of shore land around the bay for $36,000,000, draining and walling it for $27,000,000, and spending $50,000,000 more on buildings and docks.

Governor's Island, In New York Harbor. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142d72cc60

The city would cooperate with the federal government in dredging the bay to a depth of fifty feet; the sand removed would be used to build up the shoreland. The Federal government, it is suggested, would build a long jetty out into the ocean and dredge a channel to the bay. The proposed route would bring ocean steamships to New York along a channel around Coney Island and Manhattan Beach.

Part of New York's Four Hundred and Four Miles of Docks. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142da83667

The bay is dotted with numerous small islands. Two large new islands with a deep channel between them are proposed to be constructed in the center of the bay and a third near its entrance. These islands would furnish additional docking and warehouse space and be connected with the mainland by drawbridges, allowing the portage of freight by train to the wharf where a vessel was loading.

Meanwhile, the waterfrontage of Manhattan Island has practically been taken up.

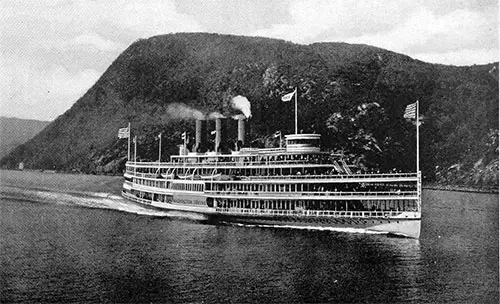

Type of Coastwise Passenger Steamer. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142ddfa6e3

Improved docks will merely facilitate the handling of the merchandise already passing over the piers, and that merchandise, coming in and going out of the port of New York in a single year, represents enough money to build six Panama canals.

It is almost equal to the stock of gold held in the United States and more than double all the British gold above ground. It is worth more than half the world's silver money. It would pay off our national debt and leave enough surplus to buy a score of archipelagoes, such as the Philippines.

The Harbor Ferry (left) and the The Ocean Ferry. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142e760d8e

Fourteen great transatlantic steamship companies partly handle this enormous trade, comprising a fleet of eighty-seven mammoth liners for transporting passengers and fast freight between the old and the new worlds. Over two hundred other steamers ply regularly between New York and cities on the Atlantic coast, the Gulf of Mexico, and South American ports. The cargo steamers and freighters are legion.

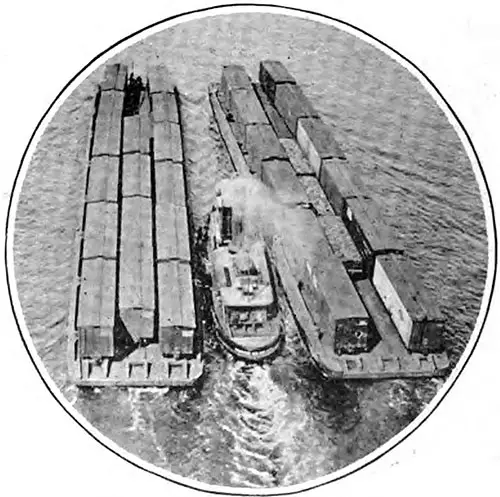

Freight Trains Afloat. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142e80dc99

The figures given represent only foreign or custom-house business of the port. The railways handle far more freight in the waters around the city than the total of this foreign commerce, vast as it is. Daily, no less than seven thousand freight cars are floated over the harbor or the rivers around Manhattan Island.

One railroad company alone, the New York, New Haven, and Hartford, floats two thousand cars daily, carrying the hundred and fifty million pairs of shoes and other manufacturing products that Massachusetts contributes to the country, including a hundred million dollars in hardware and metal goods and three or four times that value in textiles.

Where the Tramp Steamers Dock on the East River. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142eb750b8

Then, there is the harbor's passenger business. Thirty-two ferry companies operate over two hundred ferryboats and carry over half a million people daily in and out of Manhattan. The coasting steamships, the river, and Sound boats, totaling about one hundred and fifty steamship lines, also carry millions—the full amount has never been figured.

Finally, there are nearly a million emigrants who come in every year at Ellis Island, keeping company, so to speak, with half a million tourists who travel in the first and second cabins of the ocean greyhounds.

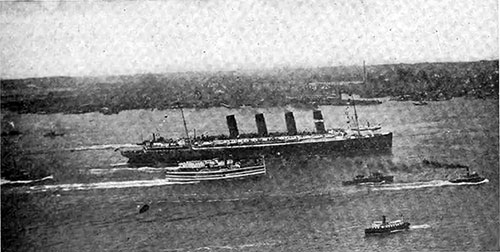

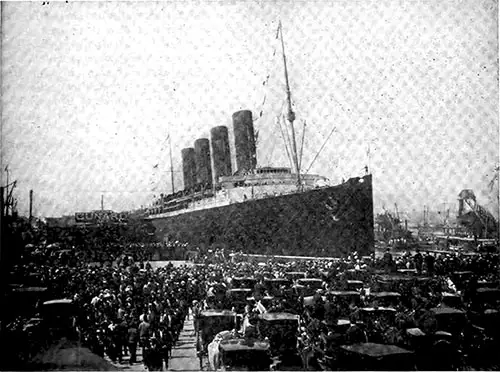

The Lusitania Passing Hoboken on her Maiden Voyage. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142eca83ce

Yet New York has manifested an interest in shipping in only one direction, and that is the protection of its waterfront from fire. In this respect, New York has set an example for the world. Her harbor firefighters are models of efficiency and have demonstrated their worth conclusively.

The fire department maintains a fleet of ten fireboats distributed so that no one is more than ten minutes away from any important dock. In a severe waterfront fire, all of them may be called on.

The newest of these boats is equal in throwing capacity to about seven modern steam fire engines; combined, the entire fleet can throw seventy-five thousand gallons a minute or as much as a moderate-sized river could discharge. These fireboats represent an investment of three-quarters of a million dollars, and the harbor fire department costs the city almost a fourth of a million annually.

Fort Pond Bay, The Port of the Future, at the Extreme End of Long Island. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142f07b26c

But it took a quarter of a century of constant agitation to stir the city to change at least a bit of its archaic wharf age, and when the cost of the Chelsea Improvements was announced—$12,000,000 to build a stretch of seven modern docks from near Fourteenth Street to Twenty-third Street along the North River—a spasm of economy seized the city government.

Luckily, the mayor and the civic officials behind the movement disregarded these conscientious scruples, and the money was appropriated. The work has been prolonged, and while the new docks will be a boon, a little forethought would have made them of far greater value to the port. The piers are 850 feet long and of corresponding width, slit with a water stretch between each of two hundred feet.

Commodious warehouses will occupy each pier, and a freight transference system will facilitate cargo handling. These piers will not be completed and ready for use for several years. Meanwhile, one eight-hundred-foot liner has already entered the port, and the air is thick with rumors of the thousand-foot vessel. When ships of this size enter the port, the Chelsea docks will be hardly more adequate than a ferry slip.

Unloading the Christmas Mail of an Ocean Liner. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142f826437

However, private enterprise has, as usual, blazed the path for civic improvements. Traffic tendencies have long pointed to South Brooklyn as the inevitable freight-shipping district of Greater New York.

Recognizing this, a private corporation, the Bush Terminal Company, acquired water frontage along the South Brooklyn shore and has erected a vast ocean terminal comprising about one hundred large warehouses, together with seven large piers, the largest in the world, each 1,340 feet long, 150 feet wide and with a water space between piers of 250 feet, affording dock room between each pier for two of the largest ocean liners ever floated. The wisdom and foresight of the company have been amply proved by the fact that twenty-five steamship lines are already using these piers.

The Coastwise Fishing Trade. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142f8c1b0d

Realizing the success of the Bush Terminal, a long strip south of Twenty-eighth Street, South Brooklyn, is being considered by the city, and if purchased, will cost $7,000,000 for the land alone, besides another strip on the same shore two miles farther south in contemplation. Plans drawn for these new docks call for an expenditure of $23,000,000 and specify that the work be completed in two years. Plans already underway indicate that the city will spend at least $60,000,000 in the next three years on harbor improvements.

The Federal government has always regarded New York as its most important naval station. Of the sixteen frowning forts guarding the southern and northern approaches to the metropolis, Fort Wadsworth, whose guns sweep the Narrows, is regarded as the most modern and powerful maintained by this government.

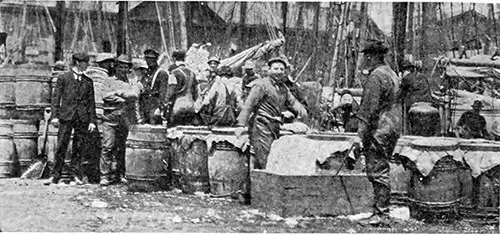

From the Wharf to the Market. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 142fd3d035

The harbor bed is protected by a network of wires several hundred miles long. On short notice, the government could mine all approaching waters so effectively that no hostile fleet would hazard an attempt to enter the harbor. In short, governmental authorities assert that New York has the best-protected harbor in the world, and the cost of creating and maintaining this formidable defense system runs into the hundreds of millions.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard, which occupies about 200 acres along the East River, is the most important of the eight Navy Yards in the country. It employs 5,000 men and provides repairs and supplies for the North Atlantic Squadron.

If Place on Broadway, The Lusitania Would Extend From Twenty-Third Street to Twenty-Sixth Street. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 143018b89f

Several medium-sized dry docks are being built, and one large dry dock is being built, capable of holding our largest battleship. Many colliers and small naval vessels are built here, although Congress has authorized the construction of only one battleship—the Connecticut—at this yard in several years. Its machine shops are the largest and most completely maintained by the American government.

The United States Army has a post on Governor's Island. Here, the Department of the East has its headquarters, under Major-General Frederick D. Grant. The largest military prison in the East and the most important arsenal in the country are located on this island, garrisoned by twelve hundred men.

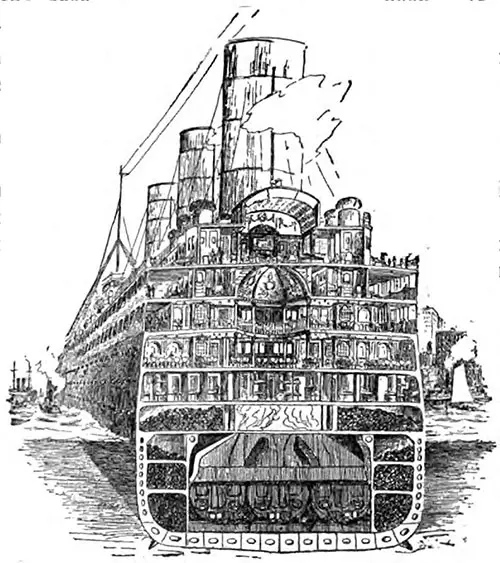

Sectional View of the Lusitania, Biggest Ship Afloat. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 143047defa

The government is spending $1,000,000 to build a reef on the island's southeast side, which will almost double its acreage. From this little island off the Battery, all the forts that protect the sea approaches are governed, as well as the Sandy Hook Proving Grounds, where all our extensive field and coast defense guns and much of our armor plate are tested.

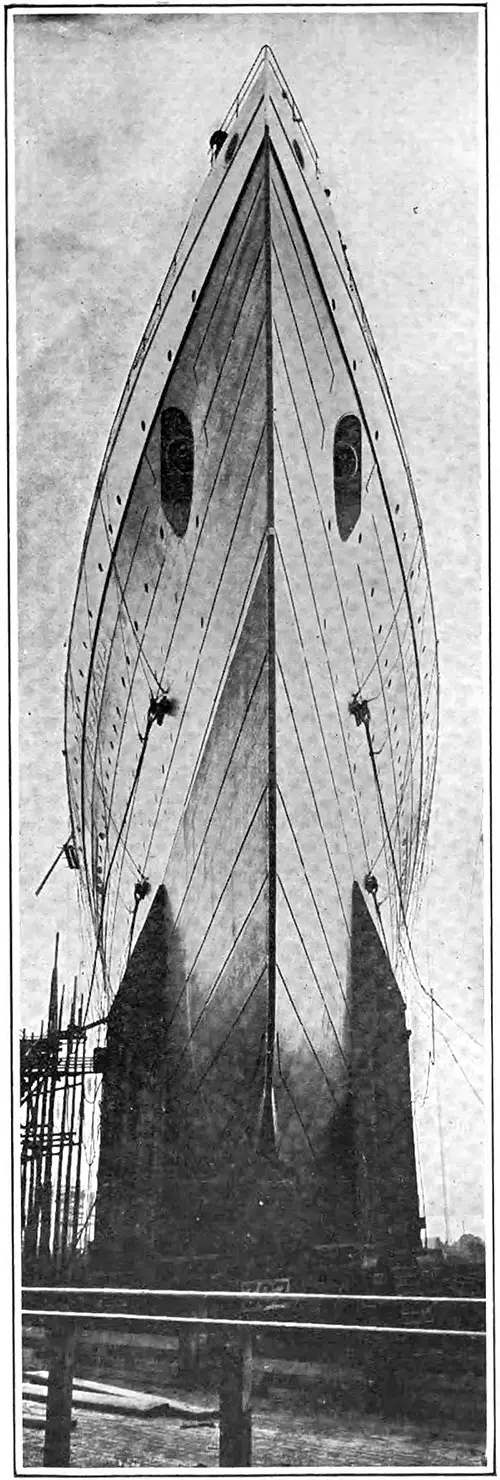

View of the Bow of the RMS Lusitania. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 14305eecbb

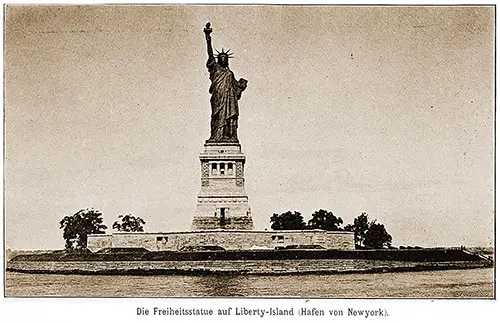

The system of harbor lighting is unequaled. Of course, the magnificent statue of the Goddess of Liberty is the most conspicuous, but the electric lighting of the Gedney Channel is far more helpful. Every buoy that marks this channel is equipped with a powerful electric light, fed utilizing heavily insulated wires stretching over the harbor bottom to shore so that ships can enter the harbor almost as well by night as by day.

The lighthouses and lightships illuminating the sea approach by night, together with the steam sirens and fog horns of daily guidance, make the roads of entry the safest of any great port in the world.

The federal government has spent millions of dollars developing the harbor as a marine and naval station. Still, on its development as a commercial port, aside from maintaining a system of lighting, it has not paid out a penny, even while spending millions on the creation of a harbor at Port Arthur, Texas, a spot of earth that the vast commercial interests of the country had never even heard of and which, in the wildest dreams of its most enthusiastic promoters, could never become a port of vital concern to the country as a whole.

However, New York, the front gate of the nation and the greatest port in the world could not get a dollar until what might have been expected happened.

The Cunard Steamship Company announced the building of the twin passenger and freight steamships Lusitania and Mauritania, the largest ships afloat. Each is eight hundred feet long and draws thirty-two feet of water.

How could these ships enter New York harbor through a channel only thirty feet in depth? Congress is puzzled over this problem. Doubtless, many ingenious devices were suggested in the committee rooms.

Finally, the construction of a new channel was authorized four years ago, and the new Ambrose channel is practically completed. This channel is seven miles long, two thousand feet wide, and forty feet deep. It leads directly across the shoals through which the main channel winds its way and saves a distance of six miles and three to five hours in passage.

Digging this ocean lane has been titanic; millions of tons have been removed and dumped far at sea. A depth of thirty-five feet is maintained throughout its entire length, and its width is less than one thousand feet.

The work will take another year to complete in detail, and its cost, originally estimated at $4,000,000, will probably exceed that sum by at least a million. At night, this channel will be illuminated by buoy lights, even more brilliantly than the Gedney channel now.

As in the case of the city, once it has set to work, the Federal government promises to continue with skill and energy.

Huge Smokestacks of the Lusitania. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 1430f8cb54

A deeper channel is already being constructed in the Kill von Kull around Staten Island to enable freighters to use that section, opening up the west coast of the island and the Jersey shore for commercial development. Harbor engineers under the Secretary of War are performing additional work in clearing and deepening Buttermilk, Bay Ridge, Red Hook, and other channels.

The most important part of the New York waterfront for the immediate future lies along the shores of South Brooklyn, and recognizing this, the government is deepening the approaching channels, which eventually will have a depth of forty feet.

In other words, after a quarter-century of sloth and negligence, both municipal and federal authorities have awakened to the necessity of providing the port of New York with those commercial facilities that are the legitimate cares of government.

Undoubtedly, the next five years will see the condemnation of the hundred miles of antique and archaic wharf structures that now cumber the shores of Manhattan Island and that portion of Brooklyn lying opposite Manhattan to make room for modern, adequate, and commodious piers and warehouses.

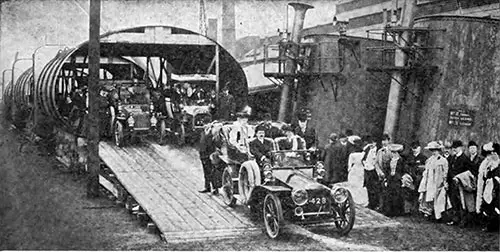

The Lusitania is "Back From Europe," Waiting to Welcome Returning Tourists. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 14310027d3

No man can estimate the future commerce, but if the port grows at the pace set during the last twenty years, New York will be doing exactly twice the business it was doing today in 1930.

Adequate facilities must be provided for an annual trade of $2,500,000,000. Already, the greater steamship companies, the modern arteries of transatlantic trade, are preparing for such development as experience has taught them to expect.

The transatlantic steamship trade, so far as America is concerned, began to become important with the first screw-propelled ship, Great Britain, entering the port in 1845, twenty years after the first steamship, the Savannah, crossed the ocean.

Since then, steamships have multiplied, and today, the Hamburg America Line maintains a schedule of three European sailings a week, and fully fifty liners clear the port every seven days.

The builders of steamships, to meet trade necessities, have sought steadily two things, great size and great speed. In 1862, the Scotia made the trip from New York to Liverpool in nine days; in 1894, the Lucania made the same passage in five and one-half days. In 1871 came the first monster ship, the Oceanic, a little over four hundred feet long. Last August came the Adriatic, 726 feet long, nearly double the length of the SS Oceanic.

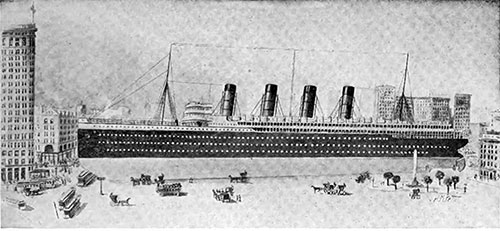

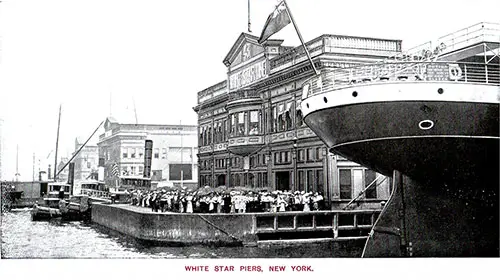

The White Star Line Piers at the Port of New York circa 1907. White Star Line Services 1907 Brochure. GGA Image ID # 144f413ce0

The record-making ships, hitherto, have not been the biggest. Still, in September, a ship that combined speed and capacity entered the port, the Lusitania, the largest ship afloat, 790 feet long, which made the passage from Queenstown to New York in five clays and fifty-four minutes.

The commercial world regards the Lusitania as the ship of the next decade— and then the thousand-foot, four-day boat will take its place!

But the ship of the decade is undoubtedly wonderful enough for the mind. If she were laid down on Broadway, her nose touching the Flatiron building, her stern would extend beyond Twenty-sixth Street—three blocks distant—and her bulk would be a third as wide again as the street.

Her decks would tower above the top of the Fifth Avenue Hotel, her stacks would exceed the twelve-story St. James building in height, and the twenty-two-story Flatiron would exceed the height of her masthead by only a few feet!

However huge this vessel is, the thousand-foot ship, which will reach a European commercial port in three to four days, is swiftly becoming a commercial necessity. In planning facilities for the port of New York, the municipality and the Federal government must face this certainty just as it must the necessity and certainty of a Jamaica Bay or even a Montauk Point transoceanic terminal.

However, while the greatest port in the world will have developed its shoreline in a generation, the commerce of two continents still awaits American exploitation, and this can only be accomplished by our merchant marine.

Of the three hundred ocean steamships that ply regularly in and out of New York Harbor today, only four cross the Atlantic and fly the American flag. The cargo steamers are showing a little better.

America really has no merchant marine outside of the Great Lakes and coast-plying boats. The 430,000 tons built last year were almost all for home service, while Great Britain's 2,000,000 tons were nearly all for foreign service.

When the above facts are realized, our merchant marine is created, and New York becomes the world's marketplace; even its thousand miles of improved waterfront will be unable to handle the traffic. New York must go without its limits for increased facilities.

Already speculation is rife and the commercial world is looking to Montauk, the easterly end of Long Island, one hundred miles from the Battery, as the port of 1950. A great bay is perfectly sheltered and 150 miles nearer Europe than New York. It is, too, nearer South America, the Panama Canal, and Africa.

Construction on a great railway system is already beginning to this point; in other words, the tracks are being laid for the traffic of half a century hence when Montauk shall be part of the port of New York—the port whose tonnage will run into the billions, and commerce into the tens of billions, the port that will serve the world and use London, Hamburg, Sydney, Cape Town, Buenos Ayres, as relay stations, when New York will be a city of fifteen millions, the greatest city and the greatest port in the history of the world.

Tugboats in New York Harbor. The Business World, December 1907. GGA Image ID # 14313c8b0a

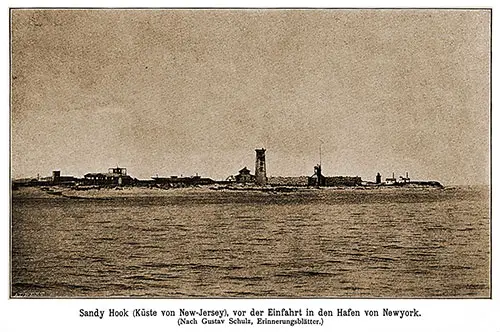

Sandy Hook (New Jersey Coast), in Front of the Entrance to New York Harbor. (After Gustav Schulz, Souvenir Sheets). Der Norddeutscher Lloyd, 1892. GGA Image ID # 2160dc7e56

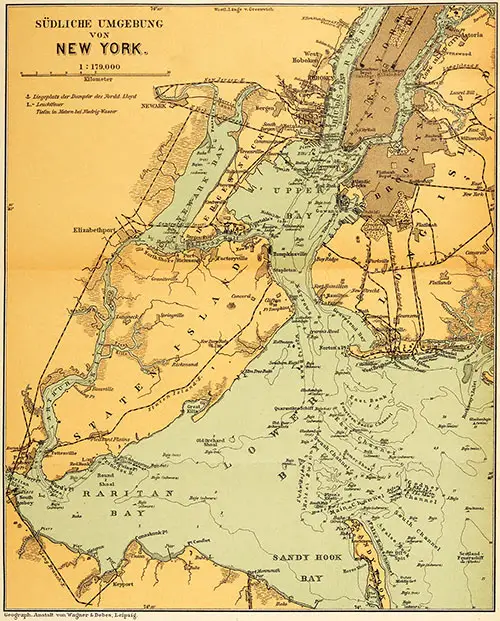

Map of New York Harbor, 1892. Der Norddeutscher Lloyd, 1892. GGA Image ID # 2161a9a2b4. Click to View Larger Image.

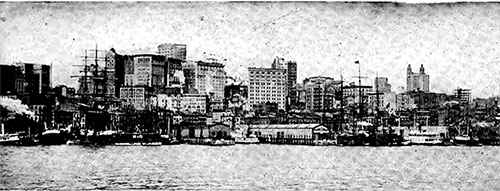

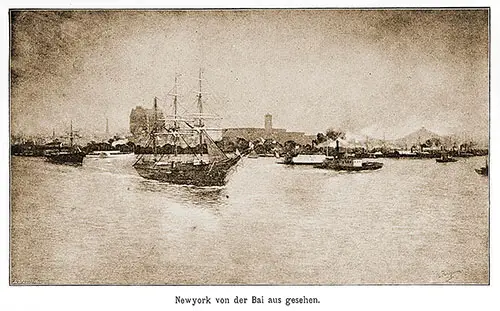

The Port of New York Seen From the Bay. Der Norddeutscher Lloyd, 1892. GGA Image ID # 21620b182c

The Statue of Liberty on Liberty Island, New York. Der Norddeutscher Lloyd, 1892. GGA Image ID # 216219b36e

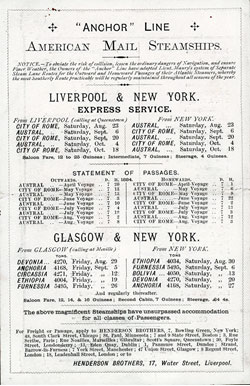

Sailing Schedules that Include the Port of New York

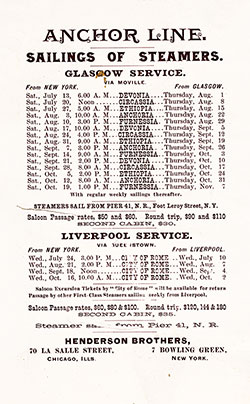

Anchor Steamship Line Sailing Schedule, 23 August 1884 to 18 October 1884

Steamers and Ocean Liners operated by Anchor Steamship Line, were scheduled for transatlantic voyages between 23 August 1884 to 18 October 1884.

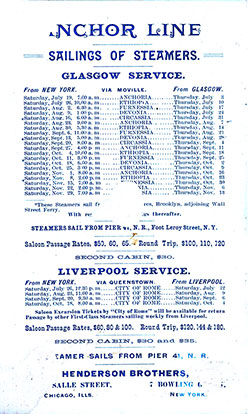

Anchor Steamship Line Sailing Schedule, 31 July 1889 to 7 November 1889

Steamers and Ocean Liners operated by Anchor Steamship Line, were scheduled for transatlantic voyages between 31 July 1889 to 7 November 1889.

Anchor Steamship Line Sailing Schedule, 19 July 1890 to 29 November 1890

Steamers and Ocean Liners operated by Anchor Steamship Line, were scheduled for transatlantic voyages between 19 July 1890 to 29 November 1890.

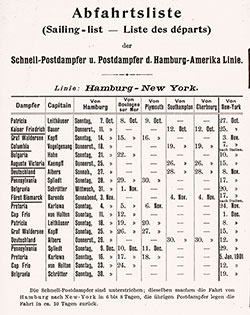

Hamburg American Line (HAPAG) Sailing Schedule, 7 October 1900 to 19 January 1901

Steamers and Ocean Liners operated by the Hamburg Amerika Linie / Hamburg American Line (HAPAG) were scheduled for transatlantic voyages between 7 October 1900 and 19 January 1901.

Bibliography

"Proposed Reorganization of the Port of New York." In "Nauticus" A Journal of Shipping, Insurance, Investments and Engineering, Volume 11, No. 141, New York, January 29, 1921, Page 26.

"The Port of New York: An Overview of the Operations and Problems," In Nauticus: A Journal of Shipping, Insurance, Investments, and Engineering, Volume 11, No. 140, New York, January 22, 1921, Pages 20-24.

Alexander R. Smith (Comp. & Ed.), Port of New York Annual, New York: Smith's Port Publishing Company, Inc., 1920.

Charles H. Cochrane, "The Greatest Port in the World," in The Business World, Volume 27, Number 11, December 1907, P. 1228-1240