Influence of Immigrant Banks and Agencies in America

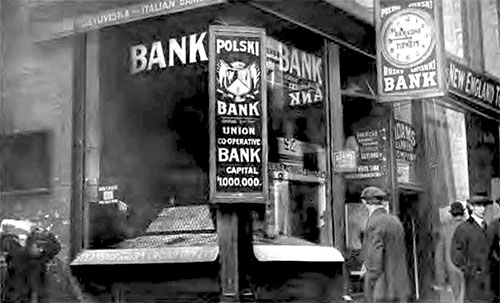

An Immigrant Bank That Gives a Personal Bond of $25,000. Polish Immigrant Bank in Boston circa 1910. Polski Bank | Union Co-Operative Bank with an Authorized Capital of $1,000,000. Immigrants Shown Congregating Outside of the Bank. Report of the Commission on Immigration on the Problem of Immigration in Massachusetts, Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Company, State Printers, 1914. GGA Image ID # 149ea7a6d6

Besides the influence brought directly to bear in Europe, an indirect influence is also exerted by the immigrant banks, ticket agencies and other similar enterprises conducted mainly by immigrants for immigrants in the United States. It is the chief business of these institutions to exchange money, send money abroad, sell steamship tickets, and do other kinds of business that directly concern the immigrant.

Naturally, the business flourishes better the more significant the savings of the immigrant and the more frequently he is ready to send such savings home. Moreover, the longer these institutions can keep the immigrant from becoming an American citizen and can keep him continually sending his profits home, the more successful the business is. Their work is constant and influential.

In the immigrant colonies of industrial towns and cities, institutions have been developed to meet the peculiar needs of the immigrant population. Each has a significant bearing upon the life of the community.

The most noteworthy of these are the immigrant banks, steamship agencies, churches, schools, and press. The most important is an institution commonly called an immigrant bank.

Unregulated Immigrant Banks [1]

Recent investigation has developed the fact that a large number of so-called banks, organized to do business with the unassimilated immigrants of recent years from southern and eastern Europe, have been established in most of our industrial localities of any size or importance.

A sizeable number-some thousands-of these institutions exist at the present time in the United States. The larger proportion are located in the manufacturing areas of the Middle States and New England, but in smaller numbers, they are doing a flourishing business in all sections in which Italians, Slavs, Magyars, or other southern and eastern Europeans are employed in considerable numbers.

Immigrant banks are found in the isolated iron ore mining camps of Minnesota and Michigan, in all bituminous mining localities of any importance in the East, Middle West, Southwest, or South, and in all industrial areas which have grown up around such industries as textile, iron, and steel, and glass manufacturing.

The importance of the business conducted by them may be seen from the fact that probably about 90 percent of the total amount of money sent abroad annually by aliens working in this country passes through the hands of immigrant bankers. [2]

More than one-half of the so-called banks also receive deposits, and, although the average deposit is less than $100 since they represent the meager accumulations of unskilled immigrant laborers to purchase steamship tickets or sending money abroad, the aggregate amount held reaches high into the millions.

The significant fact in connection with the entire system, however, is that only four States -- Ohio, New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts --have made any effort to regulate these private banks conducted by or through the patronage of aliens.

The Term Immigrant Bank a Misnomer

The term immigrant bank is a misnomer. The immigrant communities which have affixed themselves during recent years to our industrial towns and cities have many needs which can be satisfied only by a person or company familiar with the languages spoken and with the (Customs, habits, and as a manner of thought of the people).

There is money to be sent to the old country; friends and relatives are to be communicated with and brought to the United States; business affairs must be transacted in this country and in the native land, and advice is to be sought on a multitude of affairs. To meet these needs the institution popularly known as the immigrant bank has come into existence.

In many respects, the immigrant bank is practically a bureau of information and a clearing-house for necessary services to the immigrant population, and it thrives on the ignorance and lack of assimilation of the immigrant people. Its banking functions, however, while limited, involves a significant amount of money and affect the welfare of a great number of people.

The branches of business and employments carried on by the banks in addition to their usual banking functions are real estate, rental, insurance, and collecting agencies, notarial offices, labor agencies, postal substations, book, jewelry, and foreign novelty stores, saloons, groceries, butchers, barbers, boarding bosses or room renters, printers, pool-room keepers, furniture dealers and undertakers.

These combinations are typical of practically all communities, and so may be considered as fairly representing the immigrant banking business generally.

The Origin of Immigrant Banks

The connection between banking and other branches of business may be easily explained. In the mind of the immigrant, the steamship agent is the sole connecting link with the fatherland. As the representative of well-known lines, he ascribes to the agent a standing and responsibility such as he has no cause to assign to any American banking institution.

Nothing is more natural than that the immigrant should take his savings to the agent and ask that the agent send them home for him. Having made a start, it is natural that he should continue to leave with the agent for safekeeping his weekly or monthly surplus, so that he may accumulate a sufficient amount for another remittance or to buy a steamship ticket to bring his family to this country or for his own return to Europe. It is not long before the agent has a nucleus for a banking business, and his assumption of banking functions quickly follows.

Those proprietors who confine their operations to banking and steamship agencies, as distinguished from those who conduct such in connection with some other business, are usually the most intelligent men of the immigrant population of any colony or locality. They are always posse' of considerable influence, and may be political leaders in the older and more established immigrant communities.

Almost without exception, they are able to speak English and have some degree of education. Frequently they have reached their position of prominence through successful mercantile enterprise. Not a few got their start as day laborers.

In most cases, the basis of their success lies in a native ability, which is by no means necessarily the product of business experience or financial training. Native ability is not, however, the source of the success of the great number of those bankers who, in a purely personal way, are acting as custodians of their countrymen's funds.

The responsibilities imposed upon those who act as bankers for the immigrants are so light as to make the assumption of that important office dependent upon no other qualification than the would-be banker's ability to inspire the confidence of his compatriot, a matter which racial ties render comparatively easy.

There are numerous instances where strangers have gone into communities and established themselves as steamship agents and foreign-exchange dealers. Their only qualification was that they were Italians among Italians, or Magyars among Magyars.

Hundreds of saloonkeepers and grocers act as bankers without the least fitness or equipment. It is true that they become bankers only as individuals through their position as merchants. Although banking functions are more or less forced upon men of this character, and although they may be exercised in a thoroughly honorable way, the fact remains that many hundreds of thousands of dollars belonging to immigrant laborers are handled by ignorant, incompetent, or untrustworthy men.

The causes for the failure of the immigrant laborer to tum to the regular American institutions to satisfy his banking needs rather than to the less responsible men of his own race are threefold:

- The ignorance and suspicion of the immigrant;

- the fact that American institutions have not developed the peculiar facilities necessary for the handling of immigrant business; and

- the ability and willingness of the immigrant proprietor to perform for his countrymen necessary services that otherwise it would be impossible for them to obtain

Possibly the great hindrance in securing immigrant patronage for American banks lies in the alien's ignorance of the English language. Inability to read and write, necessitating the transacting of business through an interpreter, combined with a poor comprehension of the check system and other banking devices, is apt to cause him to prefer more informal banking relations.

A natural hesitancy to place confidence in strangers of other races is augmented in many cases by a positive suspicion of American institutions.

A possible explanation lies in the fact that these races, largely agricultural in character prior to coming to America, are not accustomed to the extended use of banking facilities, or, if so accustomed, they confine their relations to the financial institutions operated by the government in their respective countries.

They have learned that banks of this country are not government institutions, and for that reason look with disfavor upon them. Ignorant of American customs, unable to use the English language, and finding but little encouragement to overcome his hesitancy, the immigrant turns to the bankers of his own race as the only ones really able to perform the services he needs.

Ownership' and Organization

The tendencies of the members of different races to become bankers seem to be largely dependent upon the numerical importance of the several races in different localities and as a consequence upon the opportunity for doing business. Italians, Hebrews, Poles, Magyars, and Croatians are most frequently encountered as heads of banking institutions, although scattered representatives of other races are also often encountered.

Immigrant banks are almost without exception unincorporated. They are, as a rule, privately and individually owned. In every center of alien population, there is a very sharp competition among banks conducted by men of the different immigrant races. Although the connection with New York City in one way is very intimate, there is no close alliance through ownership. It is believed that not more than a dozen of the immigrant banks of New York City have branches in the interior.

With some notable exceptions, branch banks are not maintained. Mismanagement and dishonesty on the part of those placed in charge appear to have been the leading cause of failures in the attempts to establish branch banks. The business is essentially a local development.

Of the 110 establishments from which specific information was secured during the recent investigation by the national government, 97 reported that branches were not maintained.

Banking Functions-Deposits

These immigrant institutions have only four distinct banking functions-deposits, loans, money exchange and foreign exchange. Collections, domestic exchange, insurance, and rentals are carried on by a considerable number of banks, but the first four mentioned are the distinctive banking functions.

The receipt of deposits is as a rule merely incidental to the main functions of an immigrant bank and directly contributory to the personal interests of the proprietors.

Immigrant banks are rarely commercial or savings institutions. Deposits are usually left for temporary safekeeping rather than as interest-bearing savings accounts. Such deposits are not subject to check, and there is, therefore, seldom need of clearing arrangements.

Many so-called bankers do not openly solicit deposits and do not make a practice of receiving them, while others actively seek deposits as an important part of their business. But whatever the capacity in which the banker receives money, it is essentially a personal one in which he disposes of it.

Beyond an understanding that deposits are subject to demand at any time, there is no consideration given nor limitation implied as to their use. So far as his depositors are concerned, the immigrant banker is at liberty to use their funds to suit himself.

The most objectionable use to which deposits are usually put is that of direct investment in the proprietor's own business. Grocers and saloonkeepers have admitted that deposits are used freely, to meet current bills, or are invested outright in their concerns.

Many immigrant bankers, especially in the smaller towns where the principal profits arise from the sale of steamship tickets, redeposit the funds entrusted to them in national or State banks. Many bankers thus derive from 2 to 4 percent interest on thousands of dollars which have been deposited with them, but upon which they are making no returns.

If deposits are subject to such an active demand as to prevent their redeposit as a savings account, they are often deposited as part of the immigrant banker's checking account and thus made to yield a low rate of interest.

As a rule, the immigrant bankers are not satisfied with the small profit secured by re-depositing funds placed in their care. They seek opportunities yielding a larger return and in this way deposits come to be used for loans or investments.

The larger and best class of immigrant banks make loans, just as the banking operations. It is also extremely common for them to invest funds entrusted to them in real estate and stocks.

The most usual evidence of deposit furnished by the immigrant banker is the ordinary passbook used by American banks. In some cases, only a personal receipt or a deposit slip of the usual form is given to the depositor. Some of the smaller institutions make use of a secret word, and a few of the more irresponsible banks furnish no evidence of deposit whatsoever.

Deposits left for safekeeping are seldom allowed to accumulate to an amount greater than $100. Individual sums in excess of that amount are sometimes left for short periods, and the average savings account in some banks reaches $200 and $300. But $100 appears to be the limit of an accumulation against a remittance home.

In the table below are shown the aggregate amounts of deposits, the number of depositors, and the average amount of deposits of 31 immigrant bankers of different races, including some of all the classes of banks.

Aggregate and Average Amount of Deposits and number of depositors, in 31 immigrant banks, by race of proprietor

| Race of Proprietor | Number of Banks | Aggregate Amount of Deposits | Number of Depositors | Average Amount of Deposits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgarian | 1 | $2,8542 | 80 | $78.07 |

| Croatian | 3 | 16,585 | 248 | 66.88 |

| Greek | 3 | 21,441 | 185 | 115.90 |

| Hebrew | 2 | 19,900 | 220 | 90.45 |

| Italian | 12 | 94027 | 1,487 | 63.23 |

| Magyar | 6 | 31,195 | 596 | 52.34 |

| Polish | 2 | 12,200 | 215 | 56.74 |

| Slovak | 2 | 11,500 | 215 | 53.49 |

| TOTAL | 31 | $209,190 | 3,196 | $65.45 |

While the aggregate sum held by these 31 banks is comparatively insignificant, yet it represents the savings of over 3,000 laborers, the average of deposits being $65.45. It is obvious in this connection that the average deposit is too small to warrant bringing a suit in the event of the refusal of a banker to pay.

Transmission of Money Abroad

Immigrant banks act as agents in the transmission abroad of immigrant money [3] . The transmission is effected by means of the "money orders" of certain large banking houses which are placed in the hands of immigrant bankers and sold by them to their customers.

The amount of money sent abroad by various correspondent banking houses of immigrant banks in the two and one-half years ending June 30, 1909, is shown by the table below.

This table is a summary of carefully prepared statements furnished by four general banking houses, the financial departments of an express company and of a steamship company, and three large Italian banks, including the New York office of the Bank of Naples. These are the leading concerns through which immigrant banks transmit money abroad.

The remittances of immigrant bankers formed probably 90 percent of the total amount of money sent abroad each year by the above companies. It appears, therefore, that approximately $125,000,000 was sent abroad through these agencies by immigrant banking establishments in 1907.

The influence of the period of financial, depression after that year is apparent, transmissions through these nine houses falling from $141,047,381.92 in 1907 to $77,666,035.46 in 1908. These figures are strikingly indicative of the volume of money, which passes through the hands of the hundreds of immigrant steamship agents, saloonkeepers and men of other occupations who call themselves bankers.

Immigrant Remittances Abroad by various correspondent houses of immigrant banks, by country to which sent, January 1, 1907, to June 30, 1909.

Country |

1907 |

1908 |

January 1 to June 30, 1909 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria-Hungary | $55,315,392.85 | $28,088,754.88 | $11,011,629.97 |

| Finland | 1,442,197.66 | 1,067,028.65 | 328,395.27 |

| Germany | 906,156.99 | 685,385.26 | 268,094.26 |

| Italy | 52,081,133.86 | 28,719,115.55 | 8,226,688.89 |

| Russia | 15,241,482.89 | 11,416,009.88 | 4,477,271.05 |

| Balkan States | 2,700,000.00 | 2,440,000.00 | 1,200,000.00 |

| Scandinavian States | 7,745,432.08 | 5,980,288.60 | 2,116,446.07 |

| Other European Countries (Note 1) | 4,895,583.09 | 8,164,507.69 | 2,433,120.14 |

| Oriental Countries (Note 2) | 720,000.00 | 1,155,000.00 | 719,000.00 |

| TOTAL | $141,047,381.92 | $77,666,035.46 | $30,780,645.65 |

Note 1: Including also some transmission to Oriental Countries

Note 2: China, Japan, Syria, also Greece and Turkey

It is important to recognize that these transmittals of money do not properly constitute foreign exchange, as it is commercially and economically understood.

They are not commercial payments arising out of imports or the expenditures of tourists, but represent savings withdrawn from circulation here and sent abroad for the support of families, for payment of debts contracted prior to or in coming to this country, for investment, or for accumulation for future expenditures there. Immigrant bankers universally assert that these are the purposes for which their customers transmit funds, and this is also the opinion of the larger financial concerns through which the immigrant bankers transmit money abroad.

During die industrial depression following the financial breakdown of November, 1907, many alien workmen withdrew their deposits from the banks and returned to their native lands.

Outgoing steerage rates were very low and the immigrant wage earners calculated that the expense of going home, of living there during the depression, and o£ returning to the United States with the revival of industrial activity would be less than the cost of remaining in this country.

Those without savings, many of whom had been in the United States only a few months, in many instances found support through the assistance of immigrant bankers.

Cases are numerous where bankers exhausted their resources and brought about their own financial downfall by services of this description, their embarrassment resulting from errors in judgment as to when employment would be available.

Some banks in the small industrial localities loaned as much as $20,000 in small sums to unskilled laborers. Although the labor forces to which this assistance was extended were afterward widely scattered the bankers express themselves as certain that the obligations would be repaid.

The Unsoundness of Immigrant Banks

The unsoundness of immigrant banks, and the danger connected with banking of this character, are obvious. The United States Immigration Commission in its findings set forth the evidences of insecurity as follows:

- Immigrant banks are usually unauthorized concerns, privately owned, irresponsibly managed, and seldom subject to any efficient supervision or examination.

- They deal with a class ignorant of banking methods, distrustful of American institutions, and easily influenced by the immigrant banker.

- The affairs of the bank and of the proprietor are, as a rule, indistinguishable. As far as legal restrictions or the demands of his patrons are concerned, the proprietor is at liberty to use the funds of the bank for his own purposes.

- In general, the proprietor's investments are the only security afforded the patrons of his bank. Neither capital nor reserve is required, and, as a rule, neither is found.

- Men who operate these banks, particularly saloonkeepers, labor agents, grocers, and boarding bosses, are often ignorant and without any conception of the responsibility imposed. Methods employed by bankers of this class are often very loose and unbusinesslike, and many of the immigrant bankers, notably steamship agents, advertise in a manner that is at least misleading, if not actually fraudulent and illegal.

- Immigrant banks are radically different from other financial institutions. Their chief functions are the safekeeping of deposits and the transmitting of money abroad, and from the nature of these functions methods have arisen which are open to serious objection and should be corrected by proper governmental control.

Attempts at Regulation

Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio have attempted special legislation regulating immigrant banks. The entrance into or carrying on of the business described is in these States made contingent upon the filing of a bond. The bond is conditioned upon the faithful holding, transmission, or repayment of the money received.

In Ohio, it is further conditioned upon the selling of genuine and valid steamship or railroad tickets. A most admirable feature of the Massachusetts law is the authority given the bank commissioner to fix the amount of the bond according to the amount of business carried on by each individual concern.

The law enacted by the legislature of New York in 1910 is most comprehensive and its vigorous enforcement has proved effective. In 1912, 253 private bank inspections were made and numerous violations of the law were promptly corrected and abuses stopt. [4] It might well serve as a model for other States.

This law prohibits the receipt for deposit of sums less than $500, or the receipt of money for transmission in amounts less than $500, except by banks or trust companies incorporated under the existing banking law; provided, however, that incorporation should not be necessary where a bond in the penal sum of $100,000 had been filed, or securities for a like amount, in lieu thereof, been deposited with the banking department.

It provides further

- that the banker shall have assets amounting to at least $25,000 in excess of liabilities;

- the issuance of a license dependent upon capital, character, and reputations;

- the deposit by the banker with the State banking department of cash or securities to the amount of $25,000, or of a bond in the penal sum of $25,000;

- the filing of quarterly and special reports;

- periodical examination by the banking department of bankers who file a bond in lieu of making a deposit of cash or securities;

- regulation by the banking department of the character of investments;

- provision that all money received for transmission should be forwarded within five days from its receipt;

- the shifting of the burden of proof of transmission upon the banker;

- Regulation of the use of the word "bank" and equivalent terms

An Investigation of Immigrant Banks was conducted as part of the general Industrial Investigation of the Immigrant Commission. A number of field agents collected data from these institutions, Messrs. W. H. Ramsay and Raymond Kenny being chiefly engaged in this work. A special report was prepared on this topic to Mr. Ramsay, which, after some revision by Mr. F. J. Bailey of the editorial staff of the Commission, was published as a special document. – See Report of the U.S. Immigration Commission on Immigrant Banks, Senate Document No. 381, 61st Congress, 2nd Session.

Approximately $125,000,000 in 1907 and $70,000,000 in 1908 was sent abroad by aliens residing in this country through immigrant bankers that deal with nine of the largest banking agencies doing such business.

As a rule, immigrant banks in the interior communities do not handle foreign money except as an accommodation to their patrons, buying from them such small sums as are not exchanged upon their arrival at New York, and securing for them, usually from New York or local banks, such as they may wish on departure for Europe.

Jeremiah W. Jenks, Ph.D., LL.D. and W. Jett Lauck, "Unregulated Immigrant Banks." In Chapter VII: Immigrant Institutions, The Immigration Problem: A Study of American Immigration Conditions and Needs, Third Edition, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1913, Pages 104-118.