Inspection, Social, and Economic Conditions - 1918 (Ellis Island)

The immigrant first comes under the official control of the United States government when he arrives at the port of destination. There are a number of seaports on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts designated by the Bureau as ports of entry for immigrants. Entry at any other ports is illegal.

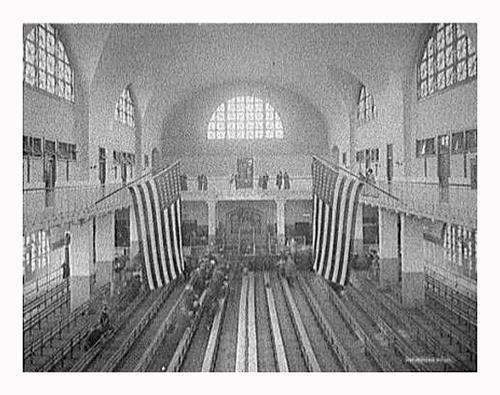

Arriving at Ellis Island - Immigrant Landing circa 1910

The facilities for the inspection and care of immigrants differ in extent in the different ports with the demands placed upon them, but the general line of procedure is the same in all. As New York has the most elaborate and complete immigrant station in the country and receives three quarters or more of all the immigrants, it may be taken as typical of the fullest development of our inspection system.

Immigrants Arriving by Steamship

A ship arriving in New York is first subject to examination by the quarantine officials. Then the immigrants are turned over to the officers of the Immigration Bureau. All aliens entering a port of the United States are subject to the immigration law, and have to submit to inspection. First or second class passage does not, contrary to a common impression, secure immunity.

"Arriving at Ellis Island." George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress). 1907.

Cabin passengers are given a preliminary inspection by the officials on board the vessel, and if they are plainly admissible, they are allowed to land without further formality. If there is any question as to their eligibility, they are taken to Ellis Island, and subjected to a closer examination. While there, they have to put up with the same accommodations as are accorded to steerage passengers..

During three months of the spring of 1910 twenty-five hundred cabin passengers were thus taken over to Ellis Island, and the commissioner in charge at that port was led to recommend that better facilities be provided for this class of immigrants. (Note 1) This recommendation was repeated in 1912.

Steerage Passengers - From Steamship to Ellis Island

The steerage passengers are loaded on to barges, rented by the steamship companies, and transferred to the immigrant station. This is located on Ellis Island, a group of small islands in the harbor, not far from the Statue of Liberty. It consists of two main parts, on one of which is located the main building, containing offices, sleeping rooms, restaurant, inspection rooms, ticket offices, etc.; on the other are the hospitals, etc. This temporary disembarkation does not constitute a legal landing; the immigrants are still nominally on shipboard, and the transportation companies are responsible for their support until they are legally landed.

"Inspection room, Ellis Island, New York." Between 1910 and 1920. Touring Turn-of-the-Century America: Photographs from the Detroit Publishing Company, 1880-1920.

After landing on the Island, the immigrants pass through a detailed process of examination, during which all the facts required by the statutes are ascertained and recorded, as far as possible. This examination consists of three main parts. The first is the medical examination made by officers of the United States Public Health and Marine Hospital Service. These inspect the immigrants for all physical weaknesses or diseases which make them liable to exclusion.

The next stage is the examination by an inspector who asks the long list of questions required by the law, in order to determine whether the alien is, for any nonphysical reason, inadmissible. If the immigrant appears to be "dearly and beyond a doubt" entitled to admission, he passes on to the discharging quarters, where is he turned over to the agents of the appropriate transportation company, or to a "missionary," or is set free to take his way to the city by the ferry.

Aliens That May Not Be Entitled to Admission to The United States

If any alien is not dearly entitled to admission, he must appear before a board of special inquiry, which goes into his case more deliberately and thoroughly, in order to determine whether he is legally admissible. Appeal from the decision of these boards, in cases provided for by the statutes, may be made either by the alien or by a dissenting member of the board. Such appeal goes through the Commissioner and the Commissioner General of Immigration to the Secretary of Commerce and Labor, whose decision is final.

Many aliens must of necessity be detained on the Island, either during investigation, or, in case they are excluded, while awaiting their return to the country from which they came. The feeding of these aliens, along with certain other services, is entrusted to "privilege holders," selected carefully by government authority.

The Business of Immigration

The volume of business transacted on Ellis Island each year is immense. There are in all about six hundred and ten officials, including ninety-five medical officers and hospital attendants, engaged in administering the law at this station. The force of interpreters is probably the largest in the world, gathered under a single roof. At other immigrant stations the course of procedure follows the same general lines, though the amount of business is very much less. (Note 2)

This is obviously one of the most difficult and delicate of all the branches of government service. Questions involving the breaking up of families, the annihilation of long-cherished plans, and a host of other intimate human relations, even of life and death itself, present themselves in a steady stream before the inspectors. Every instinct of humanity argues on the side of leniency to the ignorant, stolid, abused, and deceived immigrant.

On the other hand, the inspector knows that he is placed as a guardian of the safety and welfare of his country. He is charged with the execution of an intricate and iron-bound set of laws and regulations, into which his personal feelings and inclinations must not be allowed to enter. Any lapse into too great leniency is a betrayal of his trust. One who has not actually reviewed the cases can have no conception of the intricacy of the problems which are constantly brought up for decision.

Is it surprising that the casual and tender-hearted visitor who leans over the balcony railing or strolls through the passages, blissfully ignorant of the laws and of the meaning of the whole procedure, should think that he detects instances of brutality and hard-heartedness ? To him, the immigrants are a crowd of poor but ambitious foreigners, who have left all for the sake of sharing in the glories of American life, and are now being ruthlessly and inconsiderately turned back at the very door by a lot of cruel and indifferent officials. He writes a letter to his home paper, telling of the "Brutality at Ellis Island."

Even worse than these ignorant and sentimental critics are those clever and malicious writers who, inspired by the transportation companies or other selfish interests, paint distorted, misleading, and exaggerated pictures of affairs on Ellis Island, and to serve their own ends strive to bring into disrepute government officials who are conscientiously doing their best to perform a most difficult public duty. (Note 3)

It would not be safe to say that there never has been any brutality on Ellis Island, or that there is none now. Investigators of some reputation have given specific instances. (Note 4) It would be almost beyond the realm of possibility that in so large a number of officials, coming in daily contact with thousands of immigrants, there should be none who were careless, irritable, impatient, or vicious. How much of maltreatment there may be depends very largely upon the character and competency of the commissioner in charge. The point is, that no one is qualified to pass an opinion upon the treatment of immigrants, except a thoroughly trained investigator, equipped with a full knowledge of the laws and regulations, and an unbiased mind.

One thing in particular which impresses the dilettante observer is the haste with which proceedings are conducted, and the physical force which is frequently employed to push an immigrant in one direction, or hold him back from another. It must be admitted that both of these exist — and they are necessary. During the year 1907 five thousand was fixed as the maximum number of immigrants who could be examined at Ellis Island in one day; (Note 5) yet during the spring of that year more than fifteen thousand immigrants arrived at the port of New York in a single day. It is evident that under such conditions haste becomes a necessity.

The work has to be done with the equipment provided, and greater hardship may sometimes be caused by delay than by haste. As to the physical handling of immigrants, this is necessitated by the need for haste, combined with the condition of the immigrants. We have seen that the conditions of the voyage are not calculated to land the immigrant in an alert and dear-headed state.

The bustle, confusion, rush, and size of Ellis Island complete the work, and leave the average alien in a state of stupor and bewilderment. He is in no condition to understand or appreciate a carefully worded explanation of what he must do, or why he must do it, even if the inspector had time to give it. The one suggestion which is immediately comprehensible to him is a pull or a push; if this is not administered with actual violence, there is no unkindness in it.

Anecdotal Illustration of the Bewildering Process

An amusing illustration of the dazed state in which the average immigrant goes through the inspection is furnished by a story told by one of the officials on the Island. It is related that President Roosevelt once visited the Island, in company with other distinguished citizens. He wished to observe the effect of a gift of money on an immigrant woman, and fearing to be recognized, handed a five-dollar gold piece to another member of the party, requesting him to hand it to the first woman with a child in her arms who passed along the line.

It was done. The woman took the coin, slipped it into her dress, and passed on, without even raising her eyes or giving the slightest indication that the incident had made any different impression on her than any of the regular steps in the inspection. It would be a remarkable man, indeed, who could deal with a steady stream of foreigners, stolid and unresponsive to begin with and reduced to such a pitch of stupor, day after day, without occasionally losing his patience.

Data from the Immigration Process

The information collected at the port of entry is sufficient, when compiled and tabulated, to give a very complete and detailed picture of the character of the arriving immigrants, in so far as that can be statistically portrayed. The reports of the Commissioner General contain an elaborate set of tables, which are the principal source of accurate information on the subject. In the following pages these tables will be summarized, with the intent of bringing out the most important facts which condition the immigration problem in this country. Data from other reliable sources will be added as occasion requires.

During the period 1820 to 1912 a total of 29,611,052 immigrants have entered the United States. Of these, the Germans have made up a larger proportion than any other single race, amounting in all to 5,400,899 persons from the German Empire.

Until very recently the Irish have stood second; but as far as can be determined from the figures the Italians and natives of Austria-Hungary have now passed them. There have been, in the period mentioned, 3,511,730 immigrants from Austria-Hungary, 3,426,070 immigrants from Italy, including Sicily and Sardinia, and 3,069,625 from Ireland. But if the 1,945,812 immigrants from the United Kingdom not specified could be properly assigned, it would probably appear that Ireland could still lay claim to second place.

The other most important sources, with their respective contributions, are as follows : Russian Empire, 2,680,525; England, 2,264,284; British North American possessions, 1,322,085; Sweden, 1,095 ,940. (Note 6) When it is considered how recent is the origin of the immigration from Italy, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, the significance of these figures becomes apparent. The figures for a single recent year show very different proportions.

Thus in the year 1907, 28.2 percent of the total European immigration came from Austria-Hungary, 23.8 percent from Italy, (Note 7) and 21.6 percent from the Russian Empire, while only 3.2 percent came from the German Empire, 1.7 percent from Sweden, 2.9 percent from Ireland, and 4.7 percent from England. (Note 8)

What the ultimate effect of this sweeping change in nationality will be it is impossible to predict with any certainty; it is one of the greatest of all the problems connected with immigration, and can better be discussed in another connection. Suffice it to say for the present, that it has put an entirely new face on the question of the assimilation of the immigrant in this country.

Gender of Immigrants

In regard to the sex of the immigrants, the males have always had the predominance. During the period from 1820 to 1910, 63.8 percent of the immigrants were males, and 36.2 percent females. (Note 9) This is what might naturally be expected. The first emigration from a region is almost always an emigration of men. They have the necessary hardihood and daring to a greater extent than women, and are better fitted by nature for the work of pioneering.

After the current of emigration becomes well established, women are found joining in. Early emigrants send for their families, young men send for their sweethearts, and even some single women venture to go to a country where there are friends and relatives.

But in the majority of cases the number of males continues to exceed that of females. In the long run, there will be a greater proportion of men than of women, because of the natural differences of the sexes. In this respect, however, there has also been a change in recent years. The proportion of males is considerably larger among the new immigrants than among the old.

In the decade 1820-1830, when immigration was still in its beginning, there was a large proportion of males, amounting to 70 percent of the total. In the decades of the forties and fifties, however, the proportion of males fell to 59.5 percent and 58 per cent, respectively. But in the decade ending 1910, 69.8 percent of all the immigrants were males.

There is a general tendency for the proportion of males to rise in a year of large immigration, and fall as immigration diminishes. This can be traced with a remarkable degree of regularity throughout the modem period. It is well exemplified in the last six years.

In the year 1907, when the total immigration reached its highest record, the proportion of males also reached the highest point since 1830, 72.4 per cent. After the crisis of that year the total immigration fell off decidedly, and in 1908 the proportion of males was only 64.8 per cent. In the next year the percentage of males rose to 69.2, while the total immigration decreased slightly; but since the net gain by immigration increased in that year,' this is not a serious exception to the rule.

In 1910 the total immigration again showed a marked increase, and the percentage of males rose to 70.7. (Note 10) In 1911 there was another marked decline in immigration and the percentage of males fell to 649, while a further slight decline in 1912 was accompanied by a fall in the percentage of males to 63.2. (Note 11) This phenomenon is undoubtedly accounted for by the fact that the men come in more direct response to the economic demands of this country than the women, and hence respond to economic fluctuations more readily.

Many of the female immigrants come to join men who have established themselves on a footing of fair prosperity in this country, and are able to have them come even in a year of hard times.

An examination of the sex distribution of some of the leading races shows how thoroughly characteristic of the new immigration this excess of males is. The following table shows the percentages of the two sexes of certain chosen races for the eleven-year period 1899 to 1909 :

| Race or People | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |

| Bulgarian, Serbian, Montenegrin | 96.0 |

4.0 |

| Croatian and Slovenian | 85.1 |

14.9 |

| English | 61.7 |

38.3 |

| German | 59.4 |

40.6 |

| Greek | 954 |

4.6 |

| Hebrew | 56.7 |

43.3 |

| Irish | 47.2 |

52.8 |

| Italian, north | 78.4 |

21.6 |

| Italian, south | 78.6 |

21.4 |

| Lithuanian | 71.1 |

28.9 |

| Magyar | 72.7 |

27.3 |

| Polish | 69.2 |

30.8 |

| Ruthenian | 74.0 |

26.0 |

| Scandinavian | 61.3 |

38.7 |

| Slovak | 70.3 |

29.7 |

Comparing the entire old immigration for the period specified with the entire new immigration (European only), we find that of the former 58.5 percent were male and 41.5 percent female; of the latter 73 percent were male, and 27 percent female. (Note 12)

It is evident that the new immigration is in no sense an immigration of families, but of men, either single men, or married men who have left their wives on the other side. This is due in part to the very fact that it is a new immigration, partly to the fact that it is, to such a large degree, temporary or provisional.

An immigrant who expects to return to his native land after a few years in America is more likely to leave his wife behind him than one who bids farewell to his old home forever.

The typical old immigrant, when he has secured his competency, sends for his wife to come and join him; the typical new immigrant, under the same circumstances, in many cases returns to his native land to spend the remainder of his days in the enjoyment of his accumulated wealth. The only exception to this rule is that furnished by the Hebrews, among whom the sexes are nearly equally distributed. This is one of the many respects in which they stand apart from the rest of the new immigration.

The only race in which the female immigrants exceed the males is the Irish, and this has been the case only within recent years. During the years of the great Irish immigration the males predominated.

The matter of sex is one of the greatest importance to the United States. It is one thing to have foreign families coming here to cast in their lots with this nation permanently; it is quite another to have large groups of males coming over, either with the expectation of returning ultimately to their native land, or of living in this country without family connections, for an indefinite number of years.

Such groups form an unnatural element in our population, and alter the problem of assimilation very considerably. They are willing to work for a lower wage than if they were trying to support families in this country, and are not nearly so likely to be brought into touch with the molding forces of American life as are foreign family groups. Their habits of life, as will appear later, are abnormal, and tend to result in depredated morals and physique. Many of the most unfortunate conditions surrounding the present immigration situation may be traced to this great preponderance of males.

The one thing that can be said in favor of this state of affairs is that such a group of immigrants furnishes a larger number of workers than one more evenly distributed between the sexes. This is an argument which will appeal to many; but to many others, who have the best welfare of the country at heart, it will appear wholly inadequate to offset the serious disadvantages which result from the situation.

The Immigration Commission expresses its opinion that, in the effort to reduce the oversupply of unskilled labor in this country by restricting immigration, special discrimination should be made against men unaccompanied by wives or children. (Note 13)

Age Distribution of Immigrants by Race or Ethic Group

In regard to the age of immigrants the most striking fact is that the great bulk of them are in the middle age groups. In the year 1912 the distribution of the total immigration among the different age groups was as follows : under fourteen years, 13.6 per cent; fourteen to forty-four years, 80.9 per cent; forty-five years and over, 5.5 per cent. In the total population of the United States the respective percentages in these groups are about 30, 51, and 19.

There is only a slight difference in this respect between the new and the old immigration. Of the total European immigration for the years 1899 to 1909, the old immigration had 12.8 percent in the first age group, 80.4 percent in the second, and 6.8 percent in the third; the new immigration had 12.2 percent in the first, 83.5 percent in the second, and 4.3 percent in the third. (Note 14)

There is, however, a very marked difference between the races. This will be brought out by the following table, which shows the age distribution of certain selected races, for the year 1910 :

| Race or People | Age, Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 14 | 14 to 44 Years | 45 Years and Over | |

| Croatian and Slovenian | 4.7 |

91.0 |

3.3 |

| German | 17.0 |

75.9 |

7.1 |

| Greek | 2.6 |

96.0 |

1.4 |

| Hebrew | 25.9 |

67.9 |

6.2 |

| Irish | 7.4 |

88.3 |

4.3 |

| Italian, south | 10.4 |

83.5 |

6.1 |

| Polish | 7.6 |

89.7 |

2.7 |

Here, again, the Hebrews appear as an exception to the general rule as regards the new immigration and, in this case, as regards the total immigration.

The showing in regard to age substantiates the observation already made that our modern immigration is in no sense an immigration of families. This, too, affects the chances for assimilation very considerably. As regards the economic efficiency of the immigrants, the age distribution, added to the sex distribution, marks them as a selected group. When it is further considered that the physically and mentally feeble, and those who are unlikely to be able to earn their own living are weeded out in the process of inspection, it appears that those who look upon the immigrant as nothing more than a source of cheap labor have much reason to be pleased with the quality of our immigration. The productive power of a group of immigrants averages very much higher than a corresponding number of persons taken from the general population of the race from which they come.

Herein lies perhaps the greatest and most popular argument for immigration. It is claimed that without our foreign laboring force it would have been impossible to develop the resources of the country so rapidly and completely as they have been developed, and that if the supply were cut off now, it would seriously cripple the entire industry of the country. It is certainly true that under the present organization of industry in this country, production in many lines depends to a very important degree upon foreign labor. How much of truth there is in the deduction that without the immigrants this country would be much farther back in the industrial race than it is today, will be considered in another connection.

There are many citizens of the United States, however, who look upon the immigrant as something more than a mere productive machine. To them the proof of his economic efficiency is not sufficient. They wish to know something of his adaptability to assimilation into the American life, and of his probable contribution to the ethnic type of the United States. To such as these, there are a number of further conditions which must be considered, and which are of at least equal significance in determining the final effects of immigration upon this country.

Literacy Levels of Immigrants to the United States

Prominent among these is the intellectual quality of the immigrant. This is naturally a very difficult thing to measure. Beyond actual feeblemindedness, the only test of intellectual capacity which has received wide application is the literacy — or, as it is more frequently expressed, the illiteracy — test. This concerns the ability to read and write, and is given a great deal of weight by many students of the subject. It is not, however, necessarily an indication of intellectual capacity, but rather of education. The inability to read or write may be due to lack of early opportunity, rather than to inferior mental caliber. Nevertheless, the matter of literacy has received sufficient attention, and is in fact of sufficient importance, so that it is desirable to have the facts in this respect before us.

Two forms of illiteracy are recognized by the immigration authorities, inability to either read or write, and inability to write coupled with ability to read. The latter class is a very small one, and for all practical purposes those who are spoken of as illiterates are those who can neither read nor write. For the period of i899- 1909 the average illiteracy of all European immigrants fourteen years of age or over was 26.6 per cent. There is a marked difference between the old and new immigrants in this respect. Of the former class, during the period mentioned, only 2.7 percent of the immigrants fourteen years of age or over was illiterate; of the latter class, 35.6 per cent.

The same difference is brought out by the following table, showing the illiteracy of certain specified races :

| Race or People | Percent | Race or People | Percent |

| Scandinavian | 0.4 |

Greek | 27.0 |

| English | 1.1 |

Romanian | 34.7 |

| 'Irish | 2.7 |

Polish | 35.4 |

| German | 5.1 |

Croatian and Slovenian | 36.4 |

| Italian, north | 11.8 |

Italian, south | 54.2 |

| Magyar | 11.4 |

Portuguese | 68.2 |

| Hebrew | 25.7 |

Where there is such a marked difference between races as is exhibited in the foregoing table, it seems fair to assume that there is a corresponding difference in the intellectual condition of the respective peoples — if not in their potential capacity, at least in the actual mental equipment of the immigrants themselves. (Note 17) In fact, it is quite customary to take the degree of illiteracy as a reasonable index of the desirability of a given stream of immigration.

There seems to be considerable basis for this idea, for it appears probable that an immigrant who has had the ability and the opportunity to secure, in his home land, such a degree of education as is indicated by the ability to read and write, is better equipped for adapting himself to life in a new country than one who has not.

On the other hand, there is considerable testimony to the effect that the immigrants who have the hardest time to get along in this country are those who have a moderate degree of education, bookkeepers, mediocre musicians, clerks, etc. They are either unable or unwilling to do the menial work which their less educated countrymen perform, and are not able to compete with persons trained in this country in the occupations which they followed at home.

There are relatively few of the occupations into which the typical immigrant of today goes, and for which he is encouraged to come to this country, in which the ability to read and write adds to the efficiency of the worker to any considerable degree. It is possible that the ability to read and write may hasten the process of assimilation somewhat; it is questionable whether it adds appreciably to the economic fitness of the immigrant for life in this country.

The question of literacy as a test of immigrants has received a large amount of attention recently through its inclusion in the proposed immigration bill which barely failed of becoming a law early in the year 1913. This bill was the result of the investigations of the Immigration Commission, and embodied several of the recommendations of that body. The one upon which most of the opposition was centered was a clause providing a reading test for adult aliens.

There were certain exceptions to the rule, however, so that in its actual application the exclusion would have been limited almost wholly to adult males. The bill passed both houses of Congress, but was vetoed by the President, after a careful and judicial consideration. The Senate promptly passed the bill over the veto, but a similar action in the House failed by the narrow margin of half a dozen votes.

The agitation for a literacy test rests upon two main groups of arguments. The first class includes the efforts to show that literacy, in itself, is a desirable qualification for citizenship, economically, serially, and politically.

The second group rests on the belief that the total number of immigrants ought to be cut down, and that a literacy test is a good way to accomplish the result. It is not unlikely that this latter set of opinions predominated over the former in the minds of the adherents of the proposed measure, though it was not necessarily expressed openly.

And there is much to be said in favor of the literacy test from this point of view. In the first place, it is a perfectly definite and comprehensible test, which could be applied by the immigrant to himself before he left his native village.

In the second place, it is a test which any normal alien could prepare himself to meet if he were willing to make the effort. It does not seem too much to require of one who wishes to become a member of the American body politic, that he take the pains to equip himself with the rudiments of an education before presenting himself.

Finally, as Miss Claghorn has pointed out, (Note 18) it is a test which would react favorably upon the immigrant himself. It is impossible to tell, as noted above, just how much value attaches to literacy in the effort of the alien to maintain himself in this country. Yet without doubt there is some advantage. And perhaps there would be even more in the strengthening of character and purpose which would result from the effort to attain it.

A glance at the preceding table will show which of the immigrant races, as the immigration stream is now constituted, would be most affected by such a test. But it is not at all impossible that the passage of a literacy test by this government would have the effect of materially stimulating the progress of education in some of the more backward countries of Europe.

This tendency to illiteracy on the part of immigrants is apparently well overcome in the second generation, for among the employees in manufacturing studied by the Immigration Commission the percentage of illiteracy was lower among the native-born descendants of foreign fathers than among the native-born of native fathers. (Note 19)

Marital Status (Conjugal Condition) of Immigrants

In the year 1910 information was collected for the first time in regard to the conjugal condition of immigrants. The figures on this point are summarized in the following table, which gives the percentages of each sex, in the different age groups, who are in the different classifications as to conjugal condition.

| Marital Status | Percentages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 to 44 Years (Note 20) | 45 Years and Over | |||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||

| Single | 55.3 | 55.7 | 5.2 | 6.6 | ||||

| Married | 44.2 | 39.9 | 86.8 | 52.8 | ||||

| Widowed | 0.5 | 2.3 | 7.9 |

40.5 | ||||

| Divorced | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||

This table furnishes further verification of the fact that our present immigration is in no sense an immigration of families. More than half of all the immigrants fourteen years of age or over, of both sexes, are single.

This affects the problem of assimilation very deeply. One of the greatest forces for Americanization in immigrant families is the growing children. Where these are absent, the adults have much less contact with assimilating influences. If there was a large degree of intermarriage between these single immigrants and native Americans, the aspect of the case would be very different; but thus far, this is not the case.

Economic Gain from Immigration Into the United States

Much has been said and written about the absolute economic gain to this country through immigration. It is pointed out that each year an army of able-bodied laborers, in the prime of life, is added to our working force. To the expense of their rearing we have contributed nothing; they come to us as a free gift from the nations of Europe. Various efforts have been made to estimate the actual cash value of these alien laborers.

Professor Mayo-Smith enumerates three different ways of attacking the problem. The first is by estimating the cost of bringing up the immigrant, up to the time of his arrival in the United States. The second is by estimating his value as if he were a slave. The third is by estimating the amount of wealth he will contribute to the community before he dies, minus the cost of his maintenance — in other words, his net earnings. (Note 21)

The lack of uniformity in the results obtained by different methods and by different investigators gives weight to the opinion that it is, after all, a rather fruitless undertaking. To estimate the monetary value of a man seems to be, as yet, too much for economic science.

There is one economic contribution, however, which the immigrants make to this country which is capable of fairly accurate measurement. This is the amount of money which they bring with them when they come. For many years immigrants have been compelled to show the amount of money in their possession, and this information has been recorded, and incorporated in the annual reports.

Up to 1904, immigrants were divided into those showing less than $30 and those showing that amount or more. In that year this dividing line was raised to;s0. The total amount of money shown is also given. Thus it is possible to estimate the average amount of money shown by the immigrants of different races, and also to ascertain what proportion of them showed above or below the specified amount.

Unfortunately for the conclusiveness of the statistics, immigrants very commonly do not show all the money in their possession, but only so much as they think is necessary to secure their admission. So the total amount of money shown does not represent the total amount brought in; all that can be positively stated is that at least so much was brought in.

In 1909 the total amount of money shown was $17,331,- 828; in 1910, $28,197,745; in 1911, $29,411,488; and in 1912, $30,353,721.

| Class | Average Per Capita | |

|---|---|---|

| Based on Total Coming | Based on Total Showing | |

| Old immigration | $39.90 |

$55.20 |

| New immigration | 15.83 |

20.99 |

| Total | $22.47 |

$30.14 |

Those not showing money were for the most part children and other dependents. This shows how baseless is the impression, quite prevalent among Americans and aliens alike, that a certain specified amount of money is necessary to secure admission to this country.

Thirty dollars or fifty dollars are the amounts commonly mentioned. But since the average based on the total number showing money is barely over thirty dollars, it is plain that there must be a large number showing less than thirty dollars. In fact, some races, as, for instance, the Polish, Lithuanians, and south Italians, have an average of from twenty to twenty-five dollars for all showing money.

There is no monetary requirement for admission to the United States. While the possession of a certain amount of money is considered to add to the probability of an immigrant being able to support himself without becoming a public charge, a sturdy laborer with ten dollars in his pocket is more likely to secure admission than a decrepit old man with a good-sized bank account.

Against these large amounts of money brought in by immigrants, which represent a net gain to the total wealth of the country, must be set off the enormous amounts of money annually sent abroad by alien residents of the United States. Various efforts have been made to estimate these sums. The best is probably that of the Immigration Commission which sets the figure at a total of $275,000,000 for the year 1907, which was a prosperous year. (Note 23)

Occupations of Immigrants

The following table gives the distribution of immigrants among the different classes of occupations.

| Occupation | Percent | Occupation | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional | 1.0 |

Common laborers | 27.8 |

| Skilled laborers | 15.2 |

Servants | 10.8 |

| Farm laborers | 15.7 |

Miscellaneous | 2.1 |

| Farmers | 1.0 |

No occupation (Note 25) | 26.4 |

These figures are taken from the statements of the immigrants themselves, and represent, in so far as they are correct, the economic position of the immigrant in the country from which he came. They are not a reliable indication of the occupation into which he goes in this country.

It is evident that the great majority of the immigrants belong in general to the unskilled labor class. This is the class of labor for which there is a special demand in this country, and for which the immigrants are desired. At the same time, as Professor Commons has pointed out, (Note 26) there is also a considerable demand for skilled artisans in this country, as the peculiar conditions of American industry prevent the training of a sufficient number of all-round mechanics at home. This demand is also met from European sources. There is a great difference in this respect between the different races. (Note 27)

For instance, 29.8 percent of the English immigrants were skilled laborers, 37.9 percent of the Scotch, and 35.2 percent of the Welsh, while only 4.7 percent of the Croatians and Slovenian, 2.7 percent of the Romanians, i.8 percent of the Roumanians, and 3.5 percent of the Slovaks belonged to that class, during the period mentioned.

The highest proportion of professional is shown by the French, with 6.2 per cent. In general, the old immigration has a larger proportion in the professional and skilled groups than the new, and this difference would be much more marked if the Hebrews were excepted, as they again furnish a marked exception to the general rule of the new immigration, with 36.7 percent in the skilled labor group.

Thus far, the facts which have been brought out all have to do with the condition of the immigrants upon their arrival. They furnish a sort of a composite picture of the raw material. This is about as far as the regular statistics go. After the immigrants have left the port of arrival, the Bureau furnishes practically no information about them until they leave the country again, except an occasional special report, and, in recent years, figures concerning naturalization.

This is typical of the general attitude which characterizes the entire immigration system and legislation, and rests on the assumption that if sufficient care is exercised in the selection of immigrants, all will thenceforth be well, and no attention need be paid to them after they are in the country.

Destination of Immigrants to the United States

The final piece of information furnished in the reports is the alleged destination of the immigrants. This is of course somewhat uncertain, but in so far as it is conclusive it furnishes a preliminary dew to the distribution of our alien residents throughout the country.

The significance of the figures regarding destination, or intended future residence, may best be brought out by showing the percentages destined to the different territorial divisions of the United States. In 1910 these were as follows :

| Division | Percent |

|---|---|

| North Atlantic | 62.3 |

| South Atlantic | 2 5 |

North Central |

26.1 |

| South Central | 2.3 |

| Western | 6.1 |

| Total (Note 28) | 99.3 |

The fact that in a typical year 88.4 percent of the total immigration gave their intended future residence as the North Atlantic or North Central divisions, introduces us to some of the peculiarities of the distribution of immigrants in the United States, which will be further considered later.

Before closing our consideration of arriving immigrants it will be well to glance briefly at those who arrive, but are not admitted — in other words, the debarred. We have seen that the law has grown more and more stringent in its conditions for admission, and each new statute has tended to raise the standard.

These laws have had a powerful influence in improving the character of the applicants for admission, and with the cooperation of the transportation companies have operated to check the emigration of the manifestly undesirable to an ever greater extent. Yet there are every year considerable numbers of would-be immigrants who have to be turned back at the portals of the United States.

Disbarment of Immigrants

The lot of these unfortunates is undeniably a hard one, and they are the objects of much well-deserved sympathy. Everything possible ought to be done to limit the number of inadmissible aliens who are allowed to present themselves at the immigrant stations of this country. The farther back on the road they can be stopped, the better will the interests of humanity be served. At the same time, pity for the rejected alien ought not to be allowed to express itself in unreasonable and unwarranted attacks upon our system of admission, and the officials who administer it, as is sometimes done. (Note 29)

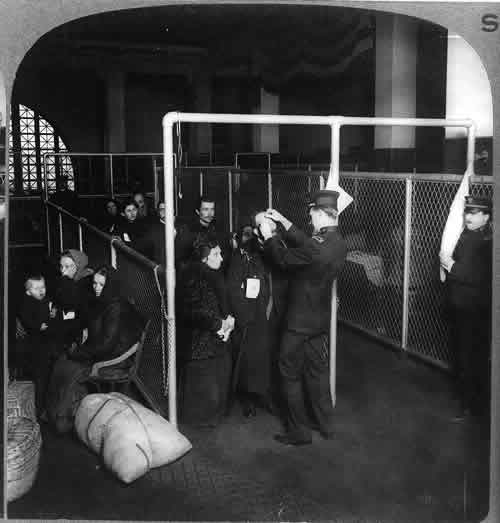

"U.S. inspectors examining eyes of immigrants, Ellis Island, New York Harbor." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. 1913.

The statistics of debarments may be indicative of the character of the applicants, of the stringency of the laws and the faithfulness of their enforcement, or of the care of the transportation companies in prosecuting their examination on the other side. It is impossible to tell from the figures themselves which of these factors account for the different fluctuations.

It is undoubtedly true that there has been, in general, a steady improvement in the care with which immigrants are selected. If, next year, a million immigrants of the same general character as prevailed sixty years ago should present themselves at our gates, the proportion of refusals would soar tremendously.

The following table gives the proportion of debarments to admissions since 1892.

| Year | 1892 | 1893 | 1894 | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 0.37 |

0.24 |

0.49 |

0.94 |

0.62 |

0.70 |

1.32 |

| Year | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

| Percent | 1.22 |

0.95 |

0.72 |

0.76 |

1.02 |

0.98 |

1.15 |

| Year | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 |

| Percent | 1.12 |

1.02 |

1.18 |

1.09 |

2.33 |

2.54 |

1.92 |

In the years 1892 to 1912, 169,132 aliens were refused admission to the United States. Of these, 58.2 percent were debarred on the grounds of pauperism or likelihood of becoming a public charge, 15.8 percent were afflicted with loathsome or dangerous contagious diseases, and 12.7 percent were contract laborers. These three leading causes account for 86.7 percent of all the debarments.

"Doctor's inspection of suspects for skin diseases, etc." 1902.

The other classes of debarred aliens specified in the reports are as follows : idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded, epileptics, insane, tuberculosis (non contagious), professional beggars, mental or physical defects likely to affect ability to earn a living, accompanying aliens, under sixteen years of age unaccompanied by parent, assisted aliens, criminals, polygamists, anarchists, prostitutes, etc., aliens who procure prostitutes, etc., under passport provision, Section 1, under provisions Chinese exclusion act, supported by proceeds of prostitution.

There has been a change in the relative importance of the three leading causes of debarment since 1892. In that year almost all the debarred aliens were paupers or likely to become a public charge or contract laborers. The first of these classes has held its own down to the present, and still stands far in advance of any other cause as regards the number refused.

The contract labor class has declined in relative importance. Loathsome and dangerous contagious diseases were comparatively unimportant until i898, when they sprang into prominence, and have since outstripped contract laborers. This was due to the classification, in 1897, of trachoma as a dangerous contagious disease. It has since led the list of diseases by a large margin.

In 1910 there were 2618 cases of trachoma out of a total of 3123 loathsome or dangerous contagious diseases. Favus comes next with 111 cases, tuberculosis next with 90, and others 304. The proportions were about the same in 1908 and 1909. In 1912 the proportion of trachoma was even greater.

Trachoma is the disease popularly known as granular lids. It attacks the conjunctiva, or mucous lining of the lids, setting up inflammation. It affects the cornea, forming ulcers, and may result in partial or total opacity, which may be permanent or temporary.

The determination of cases of true trachoma appears to be a matter of some difficulty; the examiners on Ellis Island are "instructed to regard as trachoma any case wherein the conjunctiva presents firm, well-marked granulations which do not have a tendency to disappear when the case is placed in hygienic surroundings a few days, or does not yield rapidly to ordinary treatment, even though there be no evidence of active inflammation at the time of the examination, nor appreciable discharge, nor as yet any signs of degenerative or destructive processes." (Note 30)

The necessity for great caution in this matter is increased by the fact that it is possible by medical treatment to remove the outward symptoms of trachoma so as to make it very difficult of detection, though there is no real cure, and the disease will return later. Many immigrants who are suffering from this malady take treatment of this sort before emigrating. It is stated that in London there are institutions which make a business of preparing immigrants for admission. (Note 31) Statements emanating from medical sources have recently appeared in the newspapers to the effect that trachoma is not so contagious or dangerous as has been supposed, but they appear to lack substantiation.

Favus is another name for the disease known as ring worm. It is a vegetable parasite which attacks the hair, causing it to become dry, brittle, dull, and easily pulled out. Favus is also susceptible to temporary "cures."

Summary of Immigration Findings

On the whole, the new immigration is more subject to debarment than the old, particularly for the cause of trachoma. This is a disease to which the races of southeastern Europe and Asia Minor are especially liable. A large part of the Syrians have it. In 1910 more than 3 percent of all the Syrians who presented themselves for admission were refused for this cause alone. Inability for self-support is also much more common among the new than the old.

Reviewing this survey of the arriving immigrants, we find that as respects age and sex they are a body of persons remarkably well qualified for productive labor. The predominating races are now those of southern and eastern Europe, which are of a decidedly different stock from the original settlers of this country.

There is a large percentage of illiteracy. The statistics of conjugal condition, combined with those of sex and age, show that our present immigration is in no sense an immigration of families. The great majority of the immigrants belong to the unskilled or common labor class, or else have no occupation.

The bulk of the immigrants are destined to the North Atlantic and North Central divisions of the United States. The immigrants are a selected body, as far as this can be accomplished by a strict examination under the law. In spite of the care exercised by transportation companies on the other side, a considerable number of aliens are debarred each year, mainly for the causes of disease, inability for self-support, or labor contracts. In almost all of these respects the old immigration differs to a greater or less extent from the new, with the exception of the Hebrews, who stand apart from the rest of the new immigration in a number of important particulars.

Footnotes

Note 1 : Rept. Com. Gen. of Imm., 1910, p. 135.

Note 2 : Cf. Brandenburg, B., Imported Americans, Chs. XVII and XVIII.

Note 3 : See an editorial in the New York Evening Journal, May 24, 1911.

Note 4 : Brandenburg, op. cit., p. 214

Note 5 : Rept. Com. Gen. of Imm., 1907, p. 77.

Note 6 : Rept. Imm. Com., Statistical Review, Abs., p. 17, and Rept. Comr. Gen. of Imm., 1912, pp. 68, 129. The figures of the Commission do not tally in all respects with those given in the annual Reports.

Note 7 : Figures for Italy, unless otherwise specified, include Sicily and Sardinia.

Note 8 : Rept. Imm. Com., Emig. Cond. in Eur., Abs., p. 9

Note 9 : Ibid., Stat. Rev., Abs., p. 11.

Note 10 : Rept. Imm. Corn., Stat. Rev., Abs., pp. 9, 10, 11.

Note 11 : Repts. Comr. Gen. of Imm., 1911, 1912.

Note 12 : Rept. Imm. Com., Emig. Cond. in Eur., Abs., p. 13.

Note 13 : Rept. Imm. Con., Brief Statement, p. 39.

Note 14: Ibid., Emig. Cond. in Eur., Abs, p. 14.

Note 15 : Those who cau neither read nor write.

Note 16 : Rept Imm. Coin., Emig. Cond. in Eur., Abs., p. 17.

Note 17 : The percent of illiteracy in the general population of the United States, ten years of age or over, is 10.7.

Note 18 : Claghorn, Kate H., "The Immigration Bill," The Survey, Feb. 8, 1913.

Note 19 : Rept. Imm. Com., Immigrants in Manufacturing and Mining, Abs., p. 165.

Note 20 : All the immigrants under 14 were single, with the exception of one female.

Note 21 : Mayo-Smith, R., Emigration and Immigration, pp. 104 ff.

Note 22 : Rept. Imm. Coon., Emig. Cond. in Eur., Abs., p. 20.

Note 23 : Rept. Imm. Cam., Immigrant Banks, p. 69.

Note 24 : Ibid., Emig. Cond. in Eur., Abs., p. 15.

Note 25 : Including women and children.

Note 26 : Races and Immigrants in America, pp. 124-125.

Note 27 : For detailed figures of occupation by races see Rept. Imm. Com., Stat. Rev., AN , PP. 52, 53.

Note 28 : Balance to Alaska, Hawaii, Philippine Islands, and Porto Rico.

Note 29 : See Brandenburg, B., "The Tragedy of the Rejected Immigrant," Outlook, Oct. 13, 1906.

Note 30 : Stoner, Dr. George W., Immigration— The Medical Treatment of Immigrants pests, etc., p. 10.

Note 31 : There is also a flourishing business of this sort in Liverpool, Marseilles, etc Rept. Commissioner General of Immigration, 1905, pp. 50 ff.

Source: Immigration: A World Movement and Its American Significance, Henry Pratt Fairchild, New York, MacMillan Company, 1918. Chapter X: Inspection, Social and Economic Conditions of Arriving Immigrants, Pages 183-212