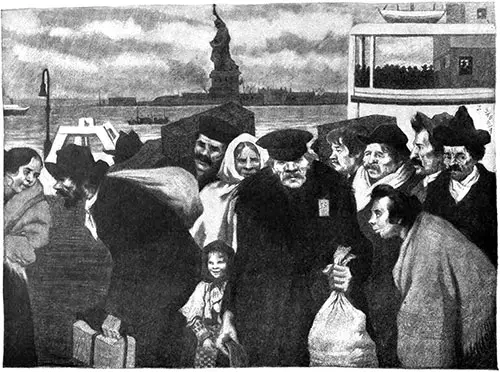

The Men Who Are To Vote - Our New Immigrants

The Crowd Hurrying By Me, Into the Great Red Bilding Beyond -- The Gateway Into America. Everybody's Magazine, October 1906. GGA Image ID # 154740fd1a

Immigrants Head Into The Great Red Building - The Gateway Into America

PRESTO Presto!" the impatient official is shouting.

"Adagio," laughs a stout, comfortable Italian in the crowd. The crowd—men, women, and children—gaily dressed, is pouring from a barge, hurrying by me and into the great red building beyond—the gateway into America.

Ellis Island on a sparkling April afternoon. A fresh salt breeze is sweeping in from the ocean. In the harbor, life is throbbing! Bustling tugs and huge steamers, scows laden with freight-cars, ferry-boats crowded with people, tall, clumsy two-decked barges packed with immigrants from ocean liners.

Shrill whistles and tooting, deep distant bellows from incoming steamers, and from the skyscrapers and canons over on Manhattan a low, incessant roar. Behind me, the Statue of Liberty is holding the torch over all. And behind that—black scurrying clouds of smoke from factory chimneys. The land of "Presto!"

Over by the New York ferry two young Hungarian-Americans stand waiting for their immigrant families. Both young men have been in America some years. One is prosperous. His derby hat is new; so is his light gray spring suit and his stiff tan shoes—all new for the occasion. His dark face is glowing with health, from the thick, curly black hair to the big red lips.

The other is clean but shabby; his threadbare, colorless clothes hang loosely from his shoulders; his cheeks are sunken and his chest is hollow. He is one of the seventy thousand consumptives in New York—made so by tenements, sweat-shops, and the nerve-racking throb of city streets. But how eagerly he watches, curling his little mustache till it nearly reaches his eyes. These eyes are large and honest; his voice is deep and pleasant.

Suddenly he stops talking and stands trembling. His friend springs forward. He follows.

The families are coming—both together. They were neighbors doubtless in Hungary. Two mothers, one in black shawl, the other in brown; an old father, tall and grizzled and powerful; two rosy young sisters who come skipping ahead.

All rush together. Passionate tears come in eyes, hysterical laughter from the mothers. One young girl suddenly throws back her head, the tears roll down her cheeks, her eyes are closed. But this is all gladness. Swift, excited questions, speech broken by kisses. –how happy they all are!

Except just for a moment, when the mother of the "failure" darts an anxious look from her son to the other—as though seeing it all. But the next moment she, too, is laughing.

We enter the building, mount to a gallery, and look clown into the great vaulted hall into twenty-two sluiceways of people, divided by high iron fences. Back in the rear of the hall they have all been examined by doctors; about one per cent. has been weeded out. And now the others come down the homestretch—with only the dreaded inspector at the desk at the mouth of each sluiceway, with his big list of questions that-stand between them and America.

The system seems perfect. The place is spotlessly clean, the air is fresh, the inspectors are kindly. The whole management is swift and precise. And this we shall find all through the building. Ellis Island is a splendid example of how the Government can run things when it really tries.

Sluiceways of the world! Allow, deep babel in a dozen different tongues. Close squeezed here are races that have been apart for tens of thousands of years— races now to be slowly welded together. How absolutely different are the faces. A broad, stolid Polish face close by an excited little Italian mother who fills the air with gestures.

Gestures rise from all the sluiceways. For the southeast of Europe loves gestures, and it is from the southeast that most of our immigrants come. Three-fourths are from Italy, Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, and South Russia. Three-fourths are peasants from farms and little hamlets. Three-fourths are unskilled laborers bringing an average of only $22 each.

Three-fourths are men under forty coming first alone, their wives and children to follow them later. They are the strong men of their countries; you can see it now as you look down into the sluiceways. They are the healthy picked out of the vast poverty-stricken areas of the southeast—the peasants on whose shoulders for centuries Europe has rested.

These men are not coming here because of the Declaration of Independence. They come moved by the deep primeval instinct of man—to get for himself and his family more of the good things of life.

A vast primeval horde. Coarse, massive, honest faces. And on these faces—big, simple, human feelings.

Just below us a huge Polish laborer stands with eyes painfully fixed on the inspector's desk ahead; he licks his dry lips in absorbing suspense. Directly behind him is a proud little Pole with a bushy yellow mustache; he seems to have been here before and to know the whole game; he nudges the big man, gives him directions, laughs, and tells how easy it is to get through. The big man grins, but then doubtfully shakes his head.

Near by stands a young Hungarian girl—perhaps eighteen, dark and tall, graceful, very slender. She is dressed in brown with a shawl of soft, dull red; the shawl has slipped down from her hair, which is rich and glossy —gathered in a big, loose coil. Her delicate face is turned up to the huge American flag that hangs just below us.

She smiles to herself—a childish, pleased, dreamy smile—forgetting all around her. Some one squeezes against the guitar under her arm. Swiftly she jerks it up out of danger, and now she holds it high before her. On the bench beside her is a big straw basket, with a pillow and a quaint blue teapot tied on top—her property.

In the next aisle is an enormous middle-aged Austrian with rosy cheeks and large, shallow, complacent blue eyes. Before him he holds a huge, gleaming brass horn—marching on America! He has but one anxiety. From his breast-pocket protrudes a long and villainous-looking Austrian cheroot, and from time to time he glances down at it longingly; twice he puts it in his mouth, but a neighbor warns him not to light.

Slowly he grows more unhappy—then indignant! Suddenly he scratches a match! But alas! up comes an inspector. "No smoking here!" is conveyed by decided gestures. The stout man frowns angrily and puts back the cheroot. On his face comes deep gloom. But soon this is all cleared away, and the eyes beam complacent as ever.

In front on the sluiceway bench sit a young Italian couple delighted at everything. The husband has an accordion, the wife a violin; and between them lies a big yellow bag full of household belongings.

All this spring, this summer, and next fall they will make music on the streets of New York or Chicago, and will earn but a few pennies a day; till at last the American "Presto" will burn into their souls, and then will they rent a hurdy-gurdy and become happy and rich.

At present the husband is in a shapeless gray home-spun suit and the wife is all shawls. He has just made a joke-pointing at the stout Austrian; and she laughs delightedly, her head thrown back.

Close behind stands a young Russian Jewess. She wears a blue tailor-made suit, well fitting and fresh from her trunk. Her dark face is turned eagerly forward. Beside her stands her old father, a Russian giant, in heavy black coat with a gray fur collar. His massive face with its broad white beard and deep-set eyes rises above all the mass of faces —a figure of power, purity, dignity.

He sees nothing around him, his head is bent, he is reading a battered old Hebrew book. For, like most old Jewish men, he is deeply religious. He reads—and the young girl looks eagerly ahead! How close will these two be one year hence? Wide apart, no doubt, in thoughts and tastes and interests, but held together still by the family affection which in the Jewish race is especially deep and enduring.

Behind him sits another daughter with two children. She, too, is absorbed, but not in religion; she is busily giving her children cold tea from a teapot in her straw valise. The old father sees, smiles, stoops, and helps her.

Down another sluice-way squeezes a stout, anxious Italian mother. A brood of eight clings to her skirts. America, liberty, equality — all these are nothing to her. Her round, swarthy face is strained, her black eyes are fixed on the desk ahead,and her lips move silently, rehearsing replies to the dreaded questions. She has learned them all before hand.

She must explain how Antonio, her husband, in New York, is very rich, earning as much as $7 a week, sleeping in a bed with a mattress on it, and eating meat often twice or three times a day. Suddenly one youngster squeezes away, cuffs a little Greek urchin in a neighboring brood, and they scuffle and go down! Frantic cries from both mothers!

Scoldings in Greek and Italian! The cars of both urchins are soundly boxed. Then again the mother stares at the desk, and slowly squeezes forward. Her eldest child is a girl of fifteen. She is dressed in a fresh white waist and soft blue shawl, and a new plaid skirt raised high to display a marvelous checked petticoat and new tan shoes. Suddenly she sees an opening ahead.

She seizes three of the youngsters, makes them lift the enormous family package tied up in sheets, and they rush on through the gate. The startled mother rushes after them, boxes the ears of the girl, and hustles all back into Europe. Then she leans over the desk and pours forth a torrent of Italian—all the answers before she is asked. The inspector laughs and nods. Joyous laughter!

The mother hugs the girl, the brood is collected round the package, the inspector points to a stairway, and they move on. The inspector is young and good-looking. The girl arranges her hair, and so goes smiling into America.

A splendid-looking mass of raw material for citizens. Muscular frames, short and tall; tanned faces. Most of the women wear clothes newly taken from the luggage; and their babies are wonderful sights, in radiant silk cloaks, in queer old-fashioned knitted hoods and caps—in a hundred different kinds of gay outer and inner garments indescribable by man, but clean and fresh.

For a great change has come into the lives of these people —and they feel it. They are come to America to get a better living!

From this hall they are pouring downstairs into a large, low room full of booths for letters and telegrams, money exchange, and railroad tickets. Here again all moves swiftly. Busy inspectors hurry about bringing order out of chaos. Kindly women from philanthropic societies are at hand to untangle individual cases.

An old Irish lady in black silk dress enters bewildered, her blue bonnet on one side, her anxious face wrinkling, lips set, eyes glaring. But up comes a uniformed inspector, who smiles reassuringly, examines her ticket, and takes her to the ticket window of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Anxiously she begins to explain.

"Never mind," says the ticket man; "done already. There you are." And out comes the ticket duly stamped.

"Wull—by all the blessed—"

But on she is hurried.

"Yes," the ticket man tells me, "I only stamped it. The ticket was sent to Ireland by her two daughters in Philadelphia. Half of the immigrants have tickets sent to 'em in Europe by their American friends or relations. But follow the old lady and you'll see the whole game."

Now she is at the post-office mailing a letter back to Dublin. A moment later, the inspector still guiding, she exchanges shillings for quarters. Then on to a telegraph booth. And again her old face grows wild:

"Now—now whatever shall I say? Only tin words? Why, now, my foine, handsome boy—how can I say annythin' at all at all in tin words? It's ridiculous. It's—why—" "Done alreadyl" smiles the operator, shoving back her card. "Your daughters will be at the station to meet you. Twenty-five cents —yes—that's it."

"Merciful saints!" She throws up her hands, and her old eyes are shining. "Shure this country is bright as—as Ireland. Now, in my town in the county of—"

"Come on, aunty, let's find your trunk." And out she goes to the open wharf. Here in huge tangles and piles are hundreds of trunks and bags and boxes. Here she is handed to another official who looks at her check. Off he goes, and in a few minutes she sits triumphant on a big straw basket tied up in ropes. This is soon rechecked, and the old lady is steered to a room, there to wait for the ferry that will take her to. Jersey City to the immigrant train in the Pennsylvania Station.

We return to the baggage. It is all handled by one company—the railroads having pooled their work. No more of the old-style "runners" beating up trade for baggage and tickets as they did in the old days at Castle Garden. The Government has stopped all that. Now all is efficiency and fair play—"bright as Ireland!"

What strange baggage you find as you wander around. Enormous coarse hemp bags with all kinds of household gods inside, making bumps and hollows. Trunks of wood and tin and queer old leather. Ancient iron-clad boxes. Once I found one bound in strips of hide; the wood was black and cracked in places; the name was "Pietro. Valoscia di Paolo, Napolia, Italia." And the box was dated 1749!

Only one-fourth of the immigrants have luggage here. The others can carry all their worldly wealth by hand.

We go back to look up the luckless people weeded out in the sluiceways.

First into the hall marked "Temporarily Detained." A young Italian girl enters just ahead—easy and smiling. She is stopped at a desk by the door, the official reads her ticket, in Italian he asks a few questions, and then he sends the following telegram to her brother in New York:

"Call Ellis Island; temporarily detained steamer Carpathia.—Marie."

This message is sent hundreds of times a week. For hundreds of young girls arrive alone with no money or just enough to last a few weeks. The danger is obvious. Of late it has been greatly lessened by care on the island; the rule is now not to deliver a girl to any man unless he is her husband, or unless he brings his wife with him.

Private societies, employment bureaus, and model boardinghouses have also done good work. But in spite of this the danger remains. In New York recently a careful investigation has shown that each year thousands of immigrant girls, corrupted by so-called "intelligence offices," are finally swallowed up in the vice of the city.

We follow her into the hall. She has just bought a bag of cookies and now sits on a bench comfortably munching. Around her are two or three hundred men, women, and children. They crowd round us eagerly and push their written cases up to be examined, for to them all Americans are officials. The operator has followed us in. He now shows the other telegram forms:

"Detained Ellis Island, steamer E—. Require proof of your ability to support."

"Detained Ellis Island, steamer E—. Require — dollars, also proof of your ability to support"

"Detained Ellis Island, steamer E--. Require — dollars for traveling expenses."

Old men and boys and women are held until they have railroad tickets, a little money, and proof that some strong man is ready to support them. "No one liable to become a pauper can be admitted." So reads the law. As a matter of fact, tens of thousands of such people do slip through, as the charity records in big cities show.

This room is hard to leave. Over in one corner five fascinating little Polish girls, in bright colored dresses and clean white embroidered kerchiefs, are making life a dark chaos for the Polish boy who sells cookies. All five keep shoving, their written cases in front of his face, clamoring that he read, and delightedly laughing at his blushes.

In other corner sit sad people, people tired and old, anxious people, people who have been here three or four days. They have had bunks and good food provided. But suspense increases. For at the end of tire days, if no friend comes, they must go before the "Board of Special Inquiry," and from there they may be deported.

Suspense—how it makes eyes shift and glisten. One afternoon not long ago in this same room I felt it deep. That morning in New York a young Jewish friend of mine, a tall, dark boy of sixteen, had come to me greatly excited:

"Please! Come quick! My old father Isaac has just landed from Russia, but I can't get him out, and I'm afraid they'll send him back!" I went with him out to the island and came to this hall.

Poor old Isaac. A tall giant of a man, but old and gray. His long quaint brown coat was mussed and torn. You could see his knees tremble. In his massive, bearded face the deep - set eyes were bewildered and anxious; his steel - rimmed spectacles had slipped to the end of his nose, as he tried vainly to read the ticket pinned to his coat. Every minute he nervously clutched at his big black satchel, which was all the property he had.

When he saw his son, his wrinkled face grew radiant. But he was so upset he could not answer my questions.

"Why is it?" he kept asking in Yiddish. "What wrong thing have I done? Five years I have waited—dreaming of my son and the new home he would make. Many times I grew afraid I would die before this time would come. But Jehovah has been kind and I have lived. I have come to spend my last days in the home of my dreams, And now—why is it? What wrong have I done? It is more than I can bear!"

Fig 06 - Immigrants Head Into The Great Red Building - The Gateway Into America

I went to one of the officials and asked him.

"Physically incapacitated," said the busy inspector. "Look for yourself. Poor old chap, what work can he do? And the boy only makes $5 a week."

We looked at Isaac. Surely he was weak. As he stared at us anxiously, his old knees wobbled in spite of him, his long fingers moved nervously, his great gray beard was bobbing, you could see his lips quiver, and on his high white forehead the sweat-beads stood out,

"Have you had some illness?" I asked him in Yiddish, through his son.

"No! no!" he cried eagerly. "When I eat again, at once I shall be strong—so strong! Look!" And he stretched out his trembling arm. It was thick and muscular. "When I eat again!"

"Eat?" I asked. "Have you eaten nothing to-day?"

" Eight days ago I have eaten," he answered "Eight days! What do you mean?" Old Isaac drew himself up proudly—to his full height:

"In the ship—deep down in the foul part of the ship, they gave us food. I looked. The food was unclean.. We old men are not like the young ones, we hold close to the religion of our fathers. And by this religion I knew that such food was forbidden by Jehovah. So I did not eat."

Swiftly all was explained; the old man was released and brought to New York. Then his son's friends prepared a feast that was "clean." And how happy he was that night!

In this same hall an old. Austrian mother was kept five days. She had lost the railroad ticket her son had sent her. Again and again they telegraphed to the small town where she said he lived, but no reply came.

"He is so fine, so strong, so rich—my Fritz!" she kept saying. "This fine dress and this bonnet he sent me. To Austria he wrote me every week. Surely—surely he will come!" She grew worse and worse. She could not sleep at night, and all day she sat by the window watching the Manhattan sky-scrapers. Her face grew haggard and lined with tears.

She was so bewildered, she could no longer answer questions. The name of the town was all she could give. There were eighteen towns of this name in various States; but the name of her son's State she had forgotten. All she knew was that Fritz lived in a town "quite near New York." Town after town was telegraphed to. Still no reply. At last it seemed hopeless; and the old lady was about to be deported.

Suddenly came a telegram:

"Hold mother! Am corning!" And four hours later another : "Don't deport my mother. I have plenty to support her. Am coming by fast train. Hold her!"

And late that afternoon a young man sleepless and wild-eyed, arrived—from Kansas! "Quite near New York."

But now at the door a uniformed official appears with a list in his hand, and at once the whole hall is commotion! Old men, women, and children spring up and squeeze eagerly forward.

"Marie Antonia Valezio! Rebecca Wagner ! Carl Johnson!" A big German, a smiling young Jewess, and a dark, meek little Italian mother with a boy and a baby—all squeeze through, while the crowd falls back disappointed. We follow the group through the door, through a long passage, and so into "Lovers' Lane." Marie and Carl and Rebecca enter a room enclosed by wire grating.

Behind us the door opens, and in comes a short, burly Italian—an "American" with gray slouch hat tipped back, big checked suit, and bright red tie; swarthy face, flashing eyes, short black mustache, and white teeth gleaming round a grin. The grins broadens! In the grated room the dark little mother jumps forward, pushes her four-year-old boy close to the grating, and holds the baby high over her head; she laughs and laughs—unsteadily, her head moving from side to side. The baby is wrapped tight in a brown shawl embroidered with big red flowers. The wee boy capers and chuckles. The baby howls!

Swiftly the inspector questions the man, then goes to the grating and questions the wife. All corresponds. The gate is opened, she is led out, and the man, still grinning (rather sheepishly, for he sees us watching), comes around and seizes the baby. Then as he bends his head his smile vanishes and his eyes glisten. Slowly he presses his big red lips to its tiny forehead---tighter and tighter. They turn and move slowly away.

Rebecca 'Wagner is a young girl wrapped in a coarse black shawl. Here comes her "American" sister, dressed in American clothes and hat and gloves. But nothing sheepish here! They come together with a rush, and go off, the "American" laughing, Rebecca crying softly.

"This spot," said the inspector solemnly, with just the ghost of a twinkle in one eye, "holds more kisses to the square inch than any spot on earth. I myself have seen about a hundred thousand, of every shape and sound.

"The other day a young Pole arrived to claim his sweetheart. He saw her, jumped the railing, rushed to the grating—and at once the kissing began! It kept on till I gently suggested from behind that he give me a few minutes of his time.

"'Is she your wife?' I asked.

"` No! But she will be. She is ready! Look—look how ready she is!'

"'Yes, she looks very ready. But the law says you can't take her till you marry her.'

"'All rightl I go to New York, I bring a priest quick.'

"`Oh, you don't need that. We have a marriage bureau here that works all day. But it's too late this afternoon; so if you want her, come tomorrow morning.'

"'If I want her? Ha, ha! Me sure come! You bet !"

To "Lovers' Lane" come anxious "American" husbands, fastidious creatures who have been educated in taste by the great American show window. No shawl-wrapped wives for them! Often they bring out complete feminine outfits. An inspector told me one instance:

A huge, solemn-faced Pole had come out for his wife and children. In his big arms before him were piled packages great and small. Suddenly he dropped them all! He had seen his family, his big face was radiant, he called eager messages across the room. Quickly he answered the inspector's questions, and a moment later—husband, wife, and children all rushed together in a joyous, laughing, kissing tangle!

But soon the careful housewife asked about those packages. And when he explained, her rosy face grew stiff with indignation. Wrathfully she pointed to her own clean shawl and her new yellow worsted gown specially made for the entrance to America. Her gestures grew swifter. She showed the two children in the clothes she had worked so hard to make ready.

The big husband expostulated. These things she had made would be splendid, fine, beautiful, very splendid—in Poland. But not in New York. He began describing what wonderful things women did with clothes in that city. He waxed enthusiastic, his face glowed, his big blue eyes sparkled!

Darker and darker grew the face of the wife, and her voice rose sharp and angry. Then the husband grew impatient. He turned and talked to the inspector very fast in English. And at his flood of strange wads his wife listened and watched in awe, and his children stared at him open-mouthed.

"What are you saying?" she asked, clutching his arm.

"Telling him to take you all back to Poland!" he cried.

The poor woman burst into tears. And when these were over, her face was meek and submissive. Then the woman inspector led them all into another room, to be dressed. Here a moment the Pole stared down at his wife, and now his massive face was rigid with suspense. Which should he try first—shoes or hat?

The next few minutes were too painful to be described. The shoes were tried first for the wife, then for the oldest boy, and at last were squeezed on the feet of the twelve year-old girl. Now the hat. It had a tall dramatic blue feather. Should the feather point forward or backward? This point was long debated, until at last the exasperated wife clapped on the hat, and then—shawl over hat—and feather crushed forever!

The dressing was still more bewildering and intricate. It was done in the privacy of a remote corner. And when husband and wife came back, the husband carried in one hand that whalebone machine which goes with female civilization. Wrathfully the good woman snatched it and cast it upon the floor. The big husband's face was rueful and subdued—but worried, watching his wife. She certainly did not look stylish.

Last year a short, stout, comfortable Sicilian arrived for his family. He entered the door, looked over at the grated room, saw his wife and four children, and suddenly stopped and stared—his jaw dropping.

"Is not that your family?" asked the inspector.

"Yes," said the man. "De wife—she Oa right! But—me have only—only I' ree child!" With uneasy forebodings the inspector went over to the grating.

"How is this?" he asked.

"Yes," stammered the wife, in Italian, greatly confused. "Little Annunzio makes four." The inspector came back to the husband. "She says you have forgotten little Annunzio."

The stout man jumped, and his black eyes popped out of his head:

"Ali, my little Annunzio!"—he lapsed into his native tongue—"I saw him last when he was just born! But—he died last year. No—no—this is not Annunzio."

The man's face slowly darkened, jealous green lights appeared in his eyes. Back went the inspector.

"He says little Annunzio is dead."

At this little Annunzio put his tiny grimy fists to his eyes and began to howl. The inspector seized him and carried him to his father. Annunzio Senior stared down at his son in amazement.

"Yes," said he, "this looks a little like Annunzio, but it cannot be, for Annunzio is dead."

Redoubled howls from the amazed and affrighted Annunzio. He was carried back to his mother. And now at last, urged by the inspector, she confessed:

"What could I do? Last year we were so poor and my husband sent so little money. So I just wrote him that little Annunzio was dead and we needed some money to bury him!"

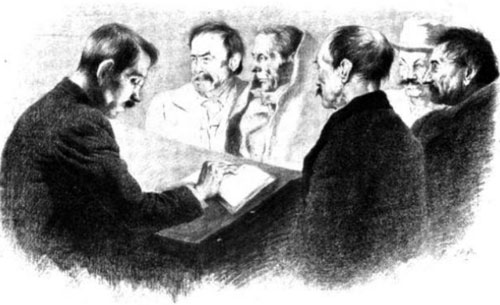

We go up now to a room where one of the "Boards of Special Inquiry" holds session. Here on a raised platform sit three judges, and before them on benches sit a score of immigrants waiting their turn. These are the cases weeded out to be individually examined. This is the last stage before deportation, except the appeal to Washington.

A young Polish mother with a crying baby in her arms comes slowly forward. From another room comes a witness, a light-haired young Pole with square, broad face, high cheek-bones, and honest brown eyes. He speaks in broken English:

"Her husband—he my brudder. He been dis country one year an' he work in a gang on de railroad. Only sometime he come home to Brooklyn. Six week ago he send de ticket to his wife an' baby to come. But t'ree week ago his gang get sent somewhere to Minnesota. An' he can't read an' write no letters, an' I can't find him where lie is or how he is."

The wife suddenly turns away—silent, but her shoulders are shaking. The man watches her hard.

"Well," he says slowly at last, "you let her in—an' I promise—I—support her an' de baby—wid my wife. An' I t'ink I find my brudder—in t'ree month maybe."

"How much do you earn?"

"Eight dollar a week."

The woman is admitted.

We go on to the "Deportation Room." Here are some two hundred men and boys. Eighty-nine are Bulgarians; they were "contract laborers" bound for the anthracite mines, but were detected at the European port by an inspector from the American labor unions; he sent warning to Ellis Island, so here they were stopped, examined, and convicted. They will all be sent back at the expense of the steamship company. But less than one per cent. of all these immigrant masses are deported.

So they come—the men who are to vote. Each year they pour in faster.

"I believe," said Commissioner Watch-horn, "that in a few years more we shall have Iwo million annually!"

From behind they are driven by famine, by religious and persecution. From in front they are drawn by the offers of jobs; by the railroads, the factories, steel works, sweatshops, and mines.

In the old country they have lived in peasant huts. They have had few teachers but village priests. They have been strong and honest and slow; their hopes and ambitions and joys have all been simple. They have been untouched by the wave of unrest that has swept through the cities and towns. They have been the most conservative of all the toilers of Europe.

But now from America the machine is calling.

What will they do? These men who have come from the slow back places of Europe suddenly into the rush of new ideas. These men with wives and children whose wants are so fast increasing. These men who begin to hear and see and think. These men who now swiftly gather into unions and discuss things. These men who are already here by millions. These men who are to vote.

Poole, Ernest "The Men Who Are To Vote," in Everybody's Magazine, Volume XV, No. I, October 1906. Illustrations by Josoph Stolla

Ernest Poole was the Author of "The Voice of Mt Street,"