In The Gateway of Nations - The Mass Immigration to The US

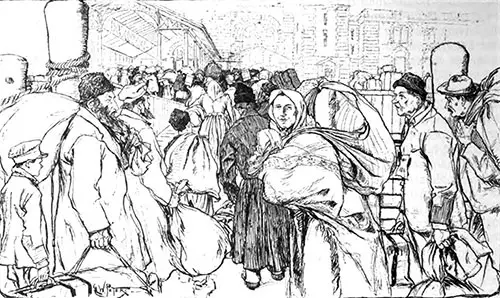

Immigrants Flocking to the US. Drawing by G. W. Peters. The Century Magazine, March 1903. GGA Image ID # 1500b7048a

Now it all came back to me : that Sunday in early June when I stood, a lonely immigrant lad, at the steamer's rail and looked out upon the New World of my dreams; upon the life that teemed ashore and afloat, and was all so strange; upon the miles of streets that led nowhere I knew of; upon the sunlit harbor, and the gay excursion-boats that went to and fro with their careless crowds; upon the green hills of Brooklyn; upon the majestic sweep of the lordly river.

I thought that I had never seen anything so beautiful, and I think so now, after more than thirty years, when I come into New York's harbor on a steamer. But now I am coming home; then all the memories lay behind. I squared my shoulders against what was coming. I was ready and eager.

But for a passing moment, there at the rail, I would have given it all for one familiar face, one voice. I knew.

How it all came back as I stood on the deck of the ferryboat plowing its way from the Battery Park to Ellis Island. They were there, my fellow-travelers of old : the men with their strange burdens of featherbeds, cooking-pots, and things unknowable, but mighty of bulk, in bags of bed-ticking much the worse for wear.

There was the very fellow with the knapsack that had never left him once on the way over, not even when he slept. Then he used it as a pillow.

It was when he ate that we got fleeting glimpses of its interminable coils of sausage, it's mysterious depths of pumpernickel and cheese that eked out the steamer's fare. I saw him last in Pittsburg, still with his sack. What long-forgotten memories that crowd stirred I The women were there, with their gaudy head-dresses and big gold earrings.

But their hair was raven black instead of yellow, and on the young girl's cheek, there was a richer hue than the pink and white I knew. The men, too, looked like swarthy gnomes compared with the stalwart Swede or German of my day. They were the same, and yet not the same.

I glanced out over the bay, and behold! all things were changed. For the wide stretch of squat houses pierced by the single spire of Trinity Church, there had come a sky-line of towering battlements, in the shelter of which nestled Castle Garden, once more a popular pleasure resort.

My eye rested upon one copper-roofed palace, and I recalled with a smile my first errand ashore to a barber's shop in the old Washington Inn, which stood where it is built.

I went to get a bath and to have my haircut, and they charged me two dollars in gold for it, with gold at a big premium; which charge, when I objected to it, was adjudged fair by a man who said he was a notary—an office I was given to understand was equal in dignity to that of a justice of peace or, of the Supreme Court.

And when still unawed, I appealed to the policeman outside, that functionary heard me through, dangling his club from his thumb, and delivered himself of a weary " G' wan, now " that ended it. There was no more.

" For the bikes o' them!" I turned sharply to the voice at my elbow and caught the ghost of a grimace on the face of the old apple-woman who sat disdainfully dealing out bananas to the" Dagos " and "sheenier" of her untamed prejudices, sole survival in that crowd of the day that was past. No, not quite the only one. I was another. She recognized it with a look and a nod.

A curiously changing procession has passed through Uncle Sam's gateway since I stood at the steamer's rail that June morning in the long ago. Then the tide of Teutonic immigration that peopled the great Northwest was still rising.

The last herd of buffaloes had not yet gone over the divide before the white-tented prairie schooner's advance; the battle of the Little Big Horn was yet unfought.

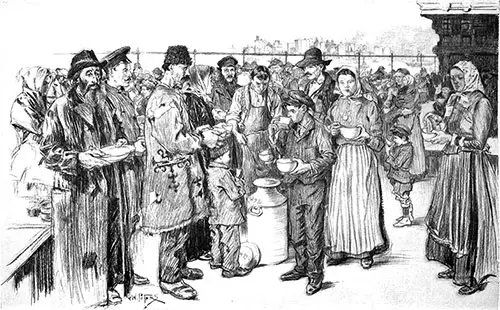

Immigrants Landing at Ellis Island, Serving Soup on the Roof Garden. Drawn by G. W. Peters. Half-Tone Plate Engraved by W. Miller. The Century Magazine, March 1903. GGA Image ID # 1500dd0f7e

A circle drawn on the map of Europe around the countries smitten with the America-unrest would, even a dozen years later than that, have had Paris for its center.

"Today," said Assistant Commissioner of Immigration McSweeney, speaking before the National Geographic Society last winter, "a circle of the same size, including the sources of the present immigration to the United States, would have its center in Constantinople."

And he pointed out that as steamboat transportation developed on the Danube, the center would be more firmly fixed in the East, where whole populations, notably in the Balkan States, are catching the infection or having it thrust upon them. Secretary Hay's recent note to the powers in defense of the Rumanian Jews told part of that story.

Even the Italian, whose country sent us half a million immigrants in the last four years, may then have to yield first place to the hill men with whom kidnapping is an established industry. I mean no disrespect to their Sicilian brother bandit. With him, it is a fine art.

While the statesman ponders the perils of unrestricted immigration, and debates with organized labor whom to shut out and how, the procession moves serenely on. Ellis Island is the nations' gateway to the promised land. There is not another such to be found anywhere. In a single day, it has handled seven thousand immigrants. " Handled " is the word; nothing short of it will do.

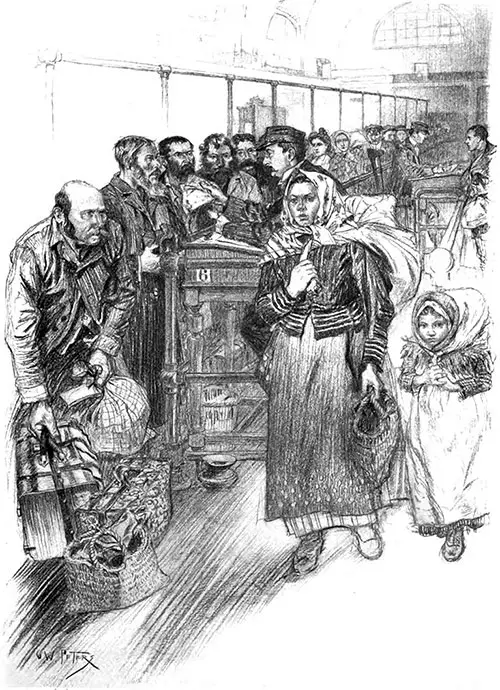

" How much you got?" shouts the inspector at the head of the long file moving up from the quay between iron rails, and, remembering, in the same breath shrieks out, " Quanto moneta? " with a gesture that brings up from the depths of Pietro's pocket a pitiful handful of paper money. Before he has it half out, the interpreter has him by the wrist, and 'with a quick movement shakes the bills out upon the desk as a dice-thrower "chucks" the ivories.

Ten, twenty, forty Lire. He shakes his head. Not much, but—he glances at the ship's manifest—is he going to friends?

" Si, si I signor," says Pietro, eagerly; his brother of the vineyard—oh, a fine vineyard! And he holds up a bundle of grape-sticks in evidence. He has brought them all the way from the village at home to set them out in his brother's field, " Ugh," grunts the inspector as he stuffs the money back in the man's pocket, shoves him on, and yells, " Wie viel geld? " at a hapless German next in line.

"They won't grow. They never do. Bring 'em just the same." By which time the German has joined Pietro in his bewilderment en route for something or somewhere, shoved on by guards, and the inspector wrestles with a " case " who is trying to sneak in on false pretenses. No go; he is hauled off by an officer and ticketed "S, I.," printed large on a conspicuous card. It means that he is held for the Board of Special Inquiry, which will sift his story.

Before they reach the door, there is an outcry and a scuffle. The tide has turned against the Italian and the steamship company. He was detected throwing the card, back up, under the heater, hoping to escape in the crowd.

He will have to go back. An eagle eye, with a memory that never lets go, has spotted him as once before deported. King Victor Emmanuel has achieved a reluctant subject; Uncle Sam has lost a citizen. Which is the better off?

A stalwart Montenegrin comes next, lugging his gun of many an ancient feud, and proves his title clear. Neither the feud nor the blunderbuss is dangerous under the American sun; they will both seem grotesque before he has been here a month. A Syrian from Mount Lebanon holds up the line while the inspector fires questions at him which it is not given to the uninitiated ear to make out.

Goodness knows where they get it all. There seems to be no language or dialect under the sun that does not lie handy to the tongue of these men at the desk. There are twelve of them.

One would never dream there were twelve such linguists in the country till he hears them and sees them; for half their talk is done with their hands and shoulders and with the official steel pen that transfixes an object of suspicion like a merciless spear, upon the point of which it writhes in vain.

The Registry Desk at Ellis Island. Drawing by G. W. Peters. Half-Tone Plate Engraved by W. Miller. The Century Magazine, March 1903. GGA Image ID # 1501218c24

The Syrian wriggles off by good luck, and tomorrow will be peddling "holy earth from Jerusalem," purloined on his way through the Battery, at half a dollar a clod. He represents the purely commercial element of our immigration, and represents it well—or ill, as you take it. He cares neither for land and cattle, nor for freedom to worship or work, but for cash in the way of trade. And he gets it. Hence more come every year.

Looking down upon the crowd in the gateway, jostling, bewildered, and voluble in a thousand tongues,—so at least it sounds, —it seems like a hopeless mass of confusion. As a matter of fact, it is all order and perfect system, begun while the steamer was yet far out at sea.

By the time the lighters are tied up at the Ellis Island wharf, their human cargo is numbered and lettered in groups that correspond with like entries in the manifest, and so are marshaled upon and over the bridge that leads straight into the United States to the man with the pert who asks questions. When the crowd is great and pressing, they camp by squads in little stalls bearing their proprietary stamp, as it were, finding one another and being found when astray by the mystic letter that brings together in the close companionship of a common peril—the pen, one stroke of which can shut the gate against them—men and women who in another hour go their way, very likely never to meet or hear of one another again on earth.

The sense of the impending trial sits visibly upon the waiting crowd. Here and there, a masterful spirit strides boldly on; the mass huddle close, with more or less anxious look. Five minutes after it is over, eating their dinner in the big waiting-room, they present an entirely different appearance.

Signs and numbers have disappeared. The groups are recasting themselves on lines of nationality and personal preference. Care is cast to the winds. A look of serene contentment sits upon the face that gropes among the hieroglyphics on the lunch-counter bulletin-board for the things that pertain to him and his:

Röget Fisk Kielbara Szynka Gotowana

" Ugh!" says my companion, homebred on fried meat, " I wouldn't eat it." No more would I if it tastes as it reads; but then, there is no telling. That lunch-counter is not half bad. From the kosher sausage to the big red apples that stare at one—at the children especially—wherever one goes, it is really very appetizing. The rage/fisk I know about; it is good.

The women guard the baggage in their seats while paler families take a look around. Half of them munch their New World sandwich with an I-care-not-what-comes-next-the-worst-is-over air; the other half scribble elaborately with stubby pencils on postal cards that are all star-spangled and striped with white and red. It is their announcement to those waiting at home that they have passed the gate and are within.

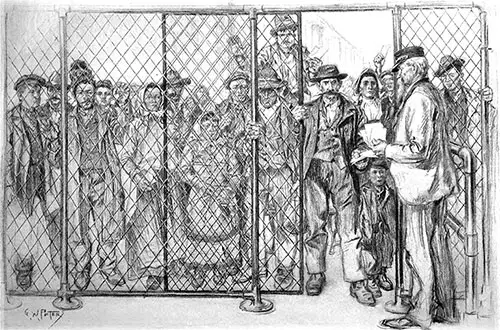

Behind carefully guarded doors wait for the "outs," the detained immigrants, for the word that will let down the bars or fix them in place immovably. The guard is for a double purpose; that no one shall leave or enter the detention —" pen " it used to be called; but the new régime under President Roosevelt's commission has set its face sternly against the term.

The law of kindness rules on Ellis Island; a note posted conspicuously invites every employee who cannot fall in with it to get out as speedily as he may. So now it is the detention." room " into which no outsider with unfathomed intentions may enter.

Here are the old, the stricken, waiting for friends able to keep them; the pitiful little colony of women without the shield of a man's name in the hour of their greatest need; the young and pretty and thoughtless, for whom one sends up a silent prayer of thanksgiving at the thought of the mob at that other gate, yonder in Battery Park, beyond which Uncle Sam's strong hand reaches not to guide or guard.

The New York Detention Room at Ellis Island. Drawing by G. W. Peters. Half-Tone Plate Engraved by R. C. Collins. The Century Magazine, March 1903. GGA Image ID # 15014d6386

And the hopelessly bewildered are there, often enough exasperated at the restraint, which they cannot understand. The law of kindness is put to a severe strain here by ignorance and stubbornness.

In it all they seem, some of them, to be able to make out only that their personal liberty, their "rights," are interfered with. How quickly they sprout in the gateway!

This German girl who is going to her uncle flatly refuses to send him word that she is here. She has been taught to look out for sharpers and to guard her little store well, and detects in the telegraph toll a scheme to rob her of one of her cherished silver marks.

To all reasoning she turns a deaf and defiant ear : he will find her. The important thing is that she is here. That her uncle is in Newark makes no impression on her. Is it not all America?

A name is cried at the door, and there is a rush. Angelo, whose destination, repeated with joyful volubility in every key and accent, puzzled the officials for a time, is going.

His hour of deliverance has come. " Pringvilliamas " yielded to patient scrutiny at last. It was " Springfield, Mass.," and impatient friends are waiting for Angelo up there. His countryman, who is going to his brother-in-law, but has " forgotten his American name," takes leave of him wistfully.

He is penniless, and near enough the " age limit of adaptability " to be an object of doubt and deliberation in laying down that limit, as in the case of the other that fixes the amount of money in hand to prove the immigrant's title to enter, the island is a law unto itself.

Under the folds of the big flag which drapes the tribunal of the Board of Special Inquiry, claims from every land under the sun are weighed and adjusted. It is ever a matter of individual consideration.

A man without a cent, but with a pair of strong hands and with a head that sits firmly on rugged shoulders, might be better material for citizenship in every way than Mr. Moneybags with no other recommendation; and to shut out an aged father and mother for whom the children are able and willing to care would be inhuman.

The gist of the thing was put clearly in President Roosevelt's message in reference to a certain economic standard of fitness for citizenship that must govern, and does govern, the keepers of the gate.

Into it enter not only the man's years and his pocket-book, but the whole man, and he virtually decides the case. Not many, I fancy, are sent hack without good cause. The law of kindness is strained, if anything, in favor of the immigrant to the doubtful advantage of Uncle Sam, on the presumption, I suppose, that he can stand it.

But at the locked door of the rejected, those whom the Board has heard and shut out, the process stops short. At least, it did when I was there. I stopped it. It was when the attendant pointed out an ex-bandit, a black and surly fellow with the strength of a wild boar, who was wanted on the other side for sticking a knife into a man.

The knife they had taken from him here was the central exhibit in a shuddering array of such which the doorkeeper kept in his corner. That morning the bandit had "soaked " a countryman of his, waiting to be deported for the debility of old age.

I could not help it. " I hope you —" I began, and stopped short, remembering the " notice " on the wall. But the man at the door understood. " I did," he nodded. " I soaked him a couple." And I felt better. I confess it, and I will not go back to the island, if Commissioner Williams will not let me, for breaking his Law.

But I think he will, for within the hour I saw him himself " soak " a Flemish peasant twice his size for beating and abusing a child. The man turned and towered above the commissioner with angry looks, but the ordinarily quiet little man presented so suddenly a fierce and warlike aspect that, though neither understood a word of what the other said, the case was made clear to the brute on the instant, and he slunk away.

Commissioner Williams's law of kindness is all right. It is based on the correct observation that not one in a thousand of those who land at Ellis Island needs harsh treatment, but advice and help—which does not prevent the thousandth case from receiving its full due.

Two Negroes from Santa Lucia are there to keep the stranded Italian company. Mount Fettle sent them hither, only to be bounced back from an inhospitable shore.

In truth, one wintry blast would doubtless convince them it were so indeed; their look and lounging attitude betray all too clearly the careless children of the South. Gypsies from nowhere, in particular, are here with gold in heavy belts, but no character to speak of or to speak for them.

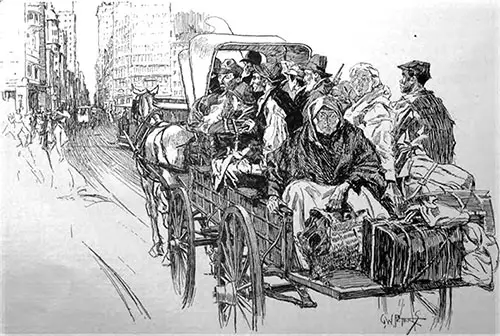

Immigrants Entering New York City. Drawing by G. W. Peters. The Century Magazine, March 1903. GGA Image ID # 1501757edf

They eye the throng making for the ferry with listless unconcern. It makes, in the end, little difference to them where they are, so long as there is a chance for a horse trade, or a horse, anyway.

There is none here, and they are impatient only to get away somewhere. Meanwhile, they live at the expense of the steamship company that brought them.

They all do. It is the penalty for differing with the commission and the Board of Special Inquiry—that and taking them back whence they came without charge.

The railroad ferries come and take their daily host straight from Ellis Island to the train, ticketed now with the name of the route that is to deliver them to their new homes, West and East. And the Battery boat comes every hour for its share.

Then the many-hued procession—the women are hooded, one and all, in their gayest shawls for the entry—is led down on a long pathway divided in the middle by a wire screen, from behind which come shrieks of recognition from fathers, brothers, uncles, and aunts that are gathered there in the holiday togs of Mulberry or Division street.

The contrast is sharp—an artist would say all in favor of the newcomers. But they would be the last to agree with him. In another week the rainbow colors will have been laid aside, and the landscape will be the poorer for it.

On the boat, they meet their friends, and the long journey is over, the new life was begun. Those who have no friends run the gantlet of the boarding-house runners; and take their chances with the new freedom, unless the missionary or "the society " of their people hold out a helping - hand. For at the barge-office gate Uncle Sam lets go. Through it, they must walk alone.

However, in the background waits the universal friend, the padrone. Enactments, prosecutions, have not availed to eliminate him. He will yield only to the logic of the very situation he created.

The process is observable among the Italians today: where many have gone and taken root, others follow, guided by their friends and no longer dependent upon the padrone.

As these centers of attraction are multiplying all over the country, his grip is loosened upon the crowds he labored so hard to bring here for his own advantage.

Observant Jews have adopted in recent days the plan of planting out their people who come here, singly or by families, and the farther apart the better, with the professed purpose of diverting as much of the inrush as may be from the city, and thus heading off the congestion of the labor market that perplexes philanthropy in Ludlow street and swells the profits of the padrone on the other side of the Bowery.

Something of the problem will be solved in that way, though not in a year, or in ten. But what of those who come after? There is still a long way from the Bosporus to China, where the bars are up.

Scarce a Greek comes here, man or boy, who is not under contract. A hundred dollars a year is the price, so it is said by those who know, though the padrone's cunning has put the legal proof beyond their reach.

And the Armenian and Syrian hucksters are " worked " by some peddling trust that traffics in human labor as do other merchants in food-stuffs and coal and oil. So the thing, as it runs down, everlastingly winds itself up again. It has not yet run down far enough to cause anybody alarm.

Three Mediterranean steamers and one from Antwerp, as I write, brought 4700 steerage passengers into port in one day, of whom only 1700 were hound for the West. The rest stayed in New York.

The padrone will be able to add yet another tenement, purchased With his profits to his holdings, In 1891, of 138;408 Italians Who landed on Ellis Island, 67,231 registered their final desalination. as Mulberry Street, and Little Italy in Harlem.

Many an emigrant vessel's keel has plowed the sea since the first brought white men greedy for gold. Some have come for conscience sake, some seeking political asylum.

Long after the beginning of the last, century, ship loads were .sold into virtual slavery to pay their passage money: Treated like cattle, dying by thousands on the voyage, and thrown into the sea with less compunction or ceremony than if they had been so much ballast; still they came: ," If crosses and tombstones could be erected on the seas, as in the Western deserts," said Assistant Commissioner McSweeney in the speech before referred to, the routes of the emigrant vessel from Europe: to America would look like crowded cemeteries."

They were not made 'Welcome. The sharpers-robbed them. Patriots. were fearful. The best leaders Of American thought mistrusted the outcome of it. The Very municipal government of New York expressed apprehension at the handful, less than ten thousand, that came over in 1819-20.

Still they came. The Know-nothings had their day, and that passed away. The country. prospered and grew great, and the new citizens prospered and grew with it.

Evil days came; and they. were scorned 'no longer; for they were found on the side of right, of an undivided Union, of financial honor, stanch and unyielding. To them, America had " spelled opportunity:" They paid back what they had received, with interest.

They saved the country they had made their own. They were of our blood. These are not; they have other traditions, not necessarily Poorer. What people has a prouder story to tell than the Italian? Who a more marvelous than the Jew.? But their traditions are not ours: Where will they stand when the strain comes?

I was concerned only with the kaleidoscope of the gateway, and I promised myself not to discuss politics, economics, or morals. Brit this is very certain: so Icing as the school-house stands over against the clean sweat-shop, clean and bright as me flag that flies over it, we need have no fear of the answer.

However perplexed the today, the tomorrow is Ours: We have the making of it. When we no longer count it worth the cost, better shut the gate on Ellis Island. We cannot be too quick about it—for their sake. The opportunity they seek here will have passed then, never to return.

Jacob A. Riis, Pictures by G. W. Peters, "In The Gateway of Nations," in The Century Magazine, Vol. LXV, No. 5, March 1903